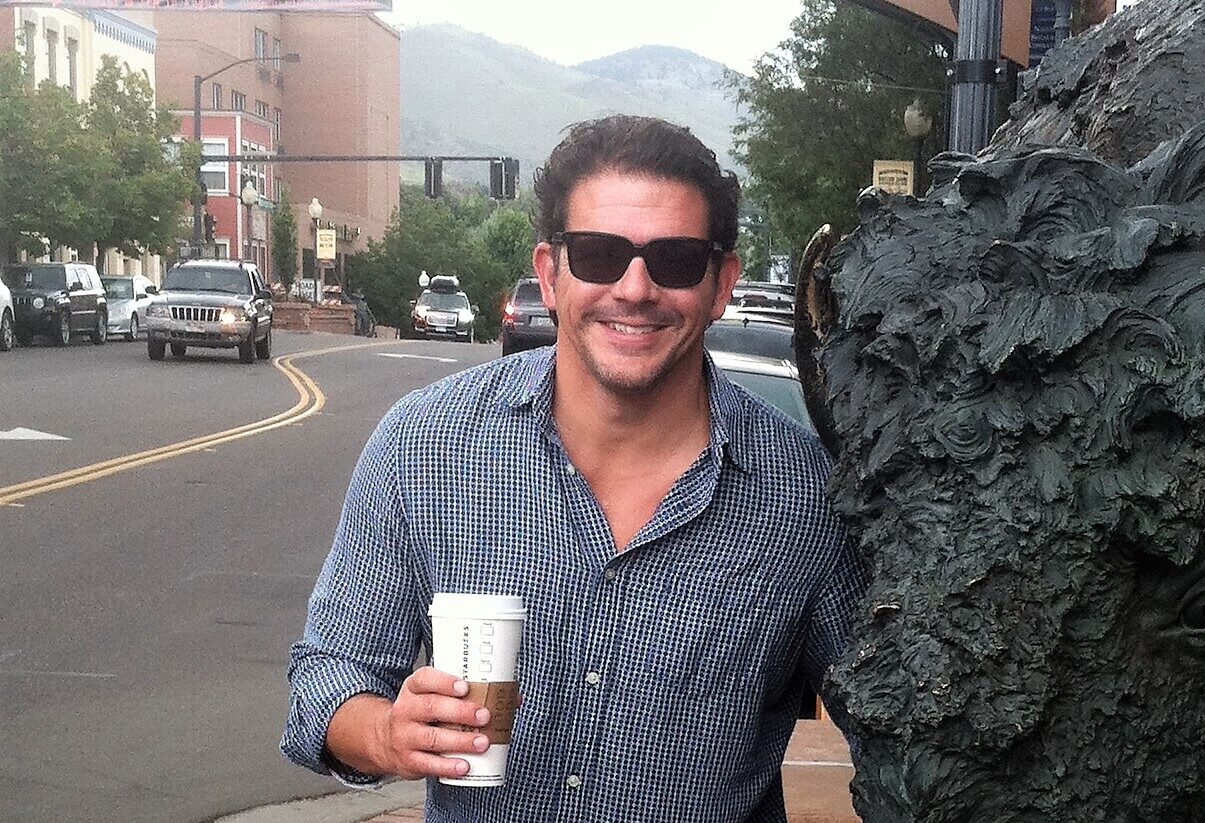

Matt Gee was an all-everything athlete growing up in Arkansas City, Kansas, before playing football for the University of Southern California (USC). Gee won two Rose Bowls and was named captain of the 1991 Trojans team. Around 2014, Gee began struggling with cognitive, mood, and behavioral issues and lost his impulse control. On December 31, 2018, Gee died at age 49. His wife Alana donated his brain to the UNITE Brain Bank, where researchers diagnosed Gee with Stage II-III (of IV) CTE. Alana is now sharing Gee’s story to share how symptoms of CTE affected the loving husband and father she knew Matt to be.

Matt Gee won. Habitually.

He set national records in high school. He won two Rose Bowls in college. He married the girl of his dreams. He ran a successful business. He once entered a raffle to win a car at his son’s high school football game and guaranteed his wife he would win the prize. And he did.

As a kid in small town Arkansas City, Kansas, Matt dominated in whatever he tried. He played both ways as a fullback and linebacker on the football team. He wrestled. He played varsity basketball and baseball. In 1987, he threw the javelin a nation-leading 243 feet and one inch.

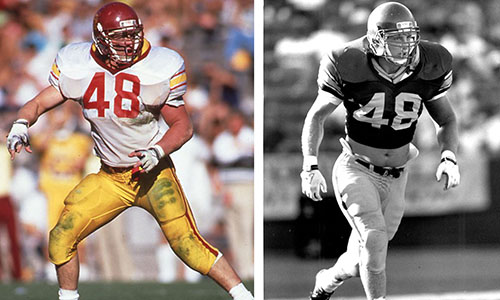

A five-star talent, Matt intended to stay close to home to play for college football powerhouse Oklahoma University. But on a track invitational at the USC’s Memorial Coliseum, the USC football coaching staff approached Matt about playing football and throwing javelin there. He was hooked and enrolled at USC in the fall of 1987.

Matt thrived in Los Angeles. He was one of two freshmen to make USC’s travelling roster for the Trojans’ 1988 Rose Bowl team. The other was USC’s wunderkind freshman quarterback Todd Marinovich.

Matt had a magnetic personality and did just as well socially at USC as he did in football.

“He would walk into a room and it would be like Norm on Cheers,” Alana Gee, his eventual wife said.

Matt’s sophomore season ended with another Rose Bowl victory for the Trojans. He met Alana over homecoming weekend that year.

“I instantly liked him,” Alana said. “He was kind. He was sweet. He was just genuine.”

Alana had graduated from USC the previous year and was weary of dating someone five years her junior. But Matt’s persistence won out and the two were inseparable from then on.

Matt was named one of USC’s captains his senior season in 1991. He led the team in tackles and had his eyes set on playing in the NFL. But an injury late in the season held him out of invitational games and lowered his draft stock. He made camp with the Los Angeles Raiders but was one of the team’s last cuts.

He lost his shot in the NFL. But even when Matt Gee lost, he kept winning. An insurance agent recruited Matt and several other college football players to work for him out of college. Matt adjusted to a new industry as easily as he did everything else in life.

“He looked at business as a competition,” Alana said. “He was a disciplined leader and hard worker.”

Matt’s success led him to start Matthew Gee & Associates, his own insurance agency in Simi Valley, California, in 1993. He and Alana married the same year. Their son Tucker was born in 1994, then Tanner in 1996, and Malia in 2000.

The business flourished but there was always enough time to pour his heart into his kids’ activities. Coach Gee made sure everybody played, had fun, and learned their sports’ fundamentals. He was known to wager buzzing his hair off if the team could accomplish a major goal.

Tucker was born with Asperger syndrome and had different interests than the rest of the family. Matt adapted and took Tucker on trips to museums across the country.

Matt and Alana were co-pilots in marriage. They completed each other’s sentences. Alana imagined a future with Matt taking Tucker around the world and enjoying life as grandparents.

“I would say to myself, ‘I can’t believe I’m living this life. I’m so fortunate,’” Alana said. “Because he was such a good man.”

Matt Gee rode a remarkable winning streak for his first 44 years of life. But he was about to enter a fight he had already lost.

He started playing tackle football when he was in third grade. Matt made 210 career tackles at USC, including 97 in his senior season.

Alana remembers Matt coming home from practice at USC often detailing how he got his “bell rung” but felt like he needed to fake being alright to maintain his standing on USC’s loaded depth chart.

On May 2, 2012, Matt and Alana were at breakfast in Simi Valley. His phone was blowing up. Junior Seau, Matt’s teammate for two seasons at USC, and a family friend of Alana’s, had died by suicide. The news rocked Matt in a way few things ever had.

Neither of them could understand. What happened to the sweet, spirted Seau they knew?

In January 2013, Seau’s family announced he had been diagnosed with CTE. Around that time, Gee slowly became a stranger to his family. He was now irritable, angry, and prone emotional outbursts.

For their first 25 years together, Matt and Alana were peas in a pod. Now, Alana’s mere presence in a room could set Matt off.

Alana had firsthand experience with anxiety through managing Tucker’s challenges with Asperger’s. She could not believe it when easygoing Matt was now noticeably anxious.

“I’m not right,” he often said to Alana.

His personality changes coincided with declining physical health. He was born with Klippel-Trenaunay Syndrome which gave him a large port-wine stain birthmark on his left arm and caused issues with his circulation.

During this time Matt became increasingly impulsive. He could no longer control how much he ate or drank. The increased consumption exacerbated his many afflictions.

Matt’s health problems were compounding on him and confounding to Alana.

“What really got me was he could do anything he put his mind to,” Alana said. “If he wanted to be the best athlete, he was the best athlete. If he wanted to be the most successful businessman, he could do that. But he couldn’t stop the drinking.”

One year, Matt was in the hospital for a total of 152 days. Giving up on Matt was never an option, but with three children in three different schools, Alana needed help. She hired someone to stay with Matt 24/7 and relied on her family to help with the children.

Matt’s cognition was slipping too. He struggled remembering things and appeared delusional at times. Initially, Alana rejected the notion that Matt’s severe downturn could be related to CTE. CTE can only be diagnosed after death and Alana was focused on finding more immediate solutions.

“I was always the fixer,” Alana said. “I couldn’t help him because I didn’t know what was going on. It was horrible.”

Around 2017, Matt started to show progress. His drinking was under control and he was regularly going to therapy. But on days where he appeared out of sorts, Alana would test Matt to see if he had been drinking. He was completely sober every time.

In December 2018, Alana followed through on a longstanding promise to take Tanner skiing. This would mean leaving Matt alone for the first time in years – a daunting proposition, but he had been sober and in good physical health of late. While she was away on the three-day trip, Alana received a call from Malia that something was off with her father. Before Alana could make it back to Simi Valley, Matt Gee died in his sleep on December 31, 2018. He was 49 years old.

Coroners found Matt had alcohol in his blood when he died. When they called Alana and asked to release his body, she demanded his brain be studied for CTE at the UNITE Brain Bank.

In addition to Junior Seau, two of Matt’s USC linebacker brethren and dear friends died in their 40’s. Their brains were not studied for CTE, but Alana saw an opportunity with Matt’s brain to provide answers for not just her tragedy but others as well.

“I know that’s what Matt would have wanted me to do because he was such a helpful, loving guy,” Alana said.

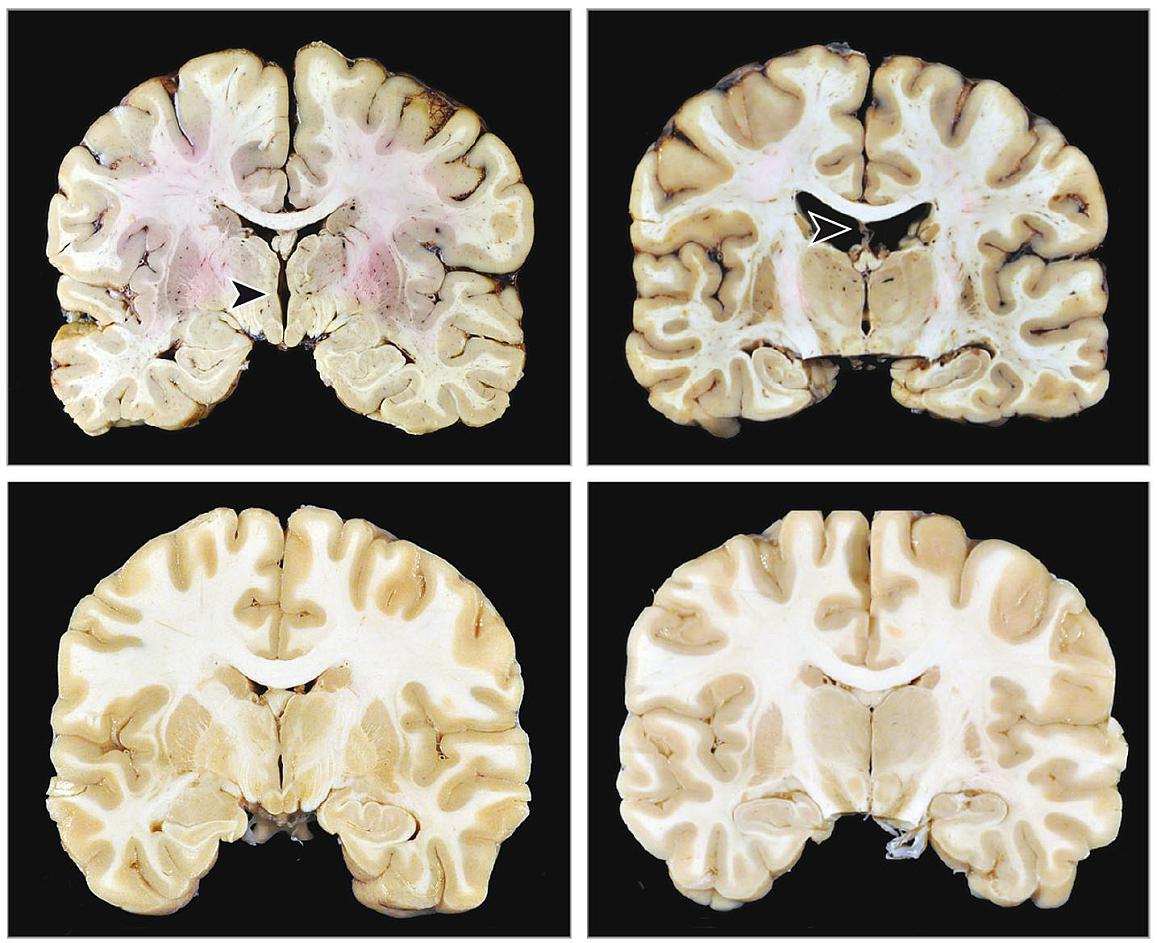

In March 2020, Brain Bank researchers told Alana that Matt was diagnosed with Stage II-III (of IV) CTE.

“I was crying so hard I couldn’t breathe,” Alana said. “It was like five years of relief after knowing in my heart that wasn’t him.”

The news also relieved the Gee children, who now had an explanation for what happened to the devoted father they grew up with. The symptoms of CTE help explain the 180-degree turn Matt’s cognition, behavior, and mood took in his last five years.

Two years after Matt’s death, Alana takes solace knowing she left no stone unturned trying to support Matt’s health. Looking to the future, she has a set of wishes to protect other families from experiencing what her family endured.

Chief among them is a way to identify CTE in living people. Diagnosing patients in life would open the door for research on treatments and a cure for the degenerative brain disease.

As researchers work toward a diagnosis, her second wish is for a protocol for physicians to manage the symptoms former contact sport athletes may experience at every stage of the disease if they do in fact have CTE. If Matt’s doctors considered his possible CTE from the beginning, they could have been better equipped to manage his impulsivity and addiction.

Alana took over Gee & Associates. As hard as she fought for him in life, she now works diligently to preserve Matt’s legacy through the agency he built and by sharing who he was before and after symptoms of CTE interrupted his life.

“Matt’s good was beyond good,” Alana said. “There are a lot of guys out there with CTE that are being blamed for a lot of things. They need vindication.”

After Matt’s diagnosis, Alana spoke to Sports Illustrated for a story on Matt and other fallen USC linebackers in the hopes her tragedy would help someone else. You can read that story here.