Nathan Stiles wanted to keep playing

SPRING HILL, Kan. — The first time Ron Stiles thought something might be wrong with his son Nathan, the boy was sprinting toward the end zone on a 65-yard touchdown run.

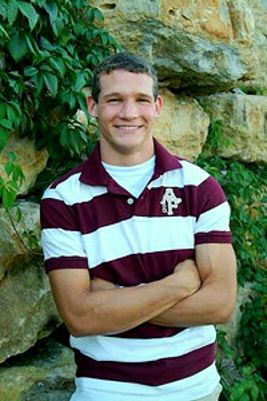

Dad couldn’t have been more proud. In his son’s final game of his senior year, the 17-year-old captain and homecoming king, a selfless soul who seemingly everyone looked up to, had broken loose for the longest touchdown run of his life. But some 20 yards before Nathan reached the end zone, Ron Stiles saw something unusual.

“It looked like something had hit him, like he was about to trip over his own feet,” Ron said. “It was strange. Something just didn’t look right.”

A few plays later, on defense, Nathan missed a tackle that led to a touchdown. “It just didn’t seem like him,” Ron said. But no one else seemed to notice. Not Nathan’s Spring Hill Broncos teammates. Not his coaches. Not even his mom, who told her husband to stop picking on their son.

But a few minutes before halftime, the kid known as “Superman” awkwardly walked off the field, screaming that his head hurt. An assistant coach grabbed Nathan and asked a string of questions: What’s your name? Where are you? What are your parents’ names? What school do you play for? With tears filling his eyes, Nathan answered every question correctly. As the coach turned to find a trainer, Nathan attempted to stand. But he fell to the ground, unconscious.

Immediately, a trainer ran over. Paramedics were called. A doctor from the opposing sidelines was summoned. Ron and Connie Stiles sprinted to their son’s side.

“He didn’t look good. His eyes were closed. He wasn’t responding. I knew it was serious,” Connie said. “But I kept thinking he would just wake up.”

The coaches urged Connie to talk to her son in hopes that he would respond. She hoped the memory of his favorite chocolate-covered snack mix might help.

“I kept saying, ‘Come on, Bubby. Come on. I’ll make you puppy chow if you wake up. You love puppy chow.”

For a brief second, Nathan raised his left arm. Then it fell.

He never moved his body again.

The decision to play

It was a few minutes before 5:30 on that summer morning in August when Nathan burst into his parents’ room to wake up his mom. Two-a-day football practices were starting, and Nathan couldn’t play until one of his parents signed a form acknowledging that they were aware of the symptoms and potential dangers of a concussion.

It was the first year that Spring Hill required a signed form to play. Given the added attention to concussion safety nationally, as well as recommendations from the Kansas State High School Activities Association, the Spring Hill School District decided that no form equaled no play.

It was just like Nathan to wait until the last minute. As smart and detail-oriented as he was in the classroom — a 4.0 GPA, a member of the National Honor Society, a Kansas Honors Scholar — he was just as absent-minded outside of it. He drove his mother crazy by losing his cell phone and his iPod. Passengers in his silver Dodge Intrepid were often nervous because he didn’t always pay attention to the road.

And so Nathan stood there that morning, handing his mom the Spring Hill Concussion Information Form. It began, “A concussion is a brain injury and all brain injuries are serious.”

“He was like, ‘Mama, Mama, sign this. I need you to sign this so I can go play,'” Connie recalled. “So I glance at the paper and it says something about concussions, blah, blah, blah. I knew there were new guidelines. I had heard about the form. So I signed it, gave it back to him and went to bed. I didn’t think twice about it.”

With concussion awareness at an all-time high, it was a scene that was surely replicated in homes all across the country last summer. Issues surrounding return to play, second-impact syndrome and even a potential connection between head trauma and ALS has put everyone from NFL commissioner Roger Goodell to Pee Wee parents on high alert. The story won’t go away. This week, the talk is of University of Texas sophomore running back Tre’ Newton quitting the sport after suffering a concussion Nov. 6. On the other end of the spectrum there’s Pittsburgh receiver Hines Ward, who criticized Steelers trainers after they refused to let him return to last Sunday’s game against New England following a suspected concussion.

On the morning Nathan handed his mom that piece of paper, he wasn’t thinking about any of this. He had no idea what was ahead. He had no clue that two months later, he’d be diagnosed with a concussion. Or that 10 days after that, in his second game back, he would find himself unconscious on the sideline, fighting for his life.

The Stiles family has lived in Spring Hill, a fast-growing community 35 miles southwest of Kansas City, forever. Both Ron and Connie’s great grandparents attended Spring Hill High. But on that night, Nathan would go from a kid people only knew in town to a nationally-recognized example of the potential for disaster after a brain injury.

Suddenly, the sentence on the concussion awareness form that read “all concussions are potentially serious and may result in complications including prolonged brain damage and death” referred to him.

And Nathan wasn’t even sure he wanted to play football this year. Basketball was his sport. Despite his chiseled arms, broad shoulders and reputation as a tough guy, he was a softy. He was the first one at church each Sunday morning so he could hug the elderly ladies as they arrived. He would sit at the kitchen table each morning and, in between bites of Cheerios and hot water, wrap his arms around his mom and tell her he loved her.

He didn’t do drugs. He didn’t drink. He didn’t believe in premarital sex. From the age of 9, he embraced God, religion and the importance of spirituality. While other little kids would watch cartoons on Sunday mornings, Nathan would watch preachers. “And then he’d tell me which ones were good and which weren’t,” Connie said. “Who does that?”

He was a jock. He was a nerd. He was churchy. “And yet he still fit in with us bad kids,” joked Adam Nunn, a close friend. “He was just like one of the guys. Only way, way better. The kid would do anything for anybody.”

Nathan hated attention. He refused to ever buy a letterman’s jacket. When a youth basketball coach once asked Nathan’s team why they couldn’t “be more like Stiles,” he fumed.

“He just loved his buddies,” his dad said. “And he never wanted them to ever be hurt or upset or embarrassed about anything.”

When those buddies decided to play football this fall, Nathan joined them. But three practices into the season, Nathan broke his hand and needed a plate and six screws to piece it back together. When he couldn’t practice, he ran sprints on the sidelines. His friends said he even lifted weights when doctors told him not to.

“He was a competitor. He always wanted to win,” said Eric Kahn, one of Nathan’s closest friends. “He was the type of guy who would always suck it up. If he was injured, he’d fight through it and see if it would just go away. And then if it didn’t, maybe he would ask somebody for help.”

So it was surprising for Connie on the morning of Oct. 2 when her son mentioned that his head hurt. The night before, she and Ron had joined Nathan on the field as he was named homecoming king. After the game, a 17-0 loss to Ottawa, Nathan went out with his friends. Everything seemed normal. Except that comment the next day.

At practice three days later, in his first contact drills since the game, Nathan complained to his coaches about his head hurting.

“Every time he made contact, he said he got a headache,” coach Anthony Orrick said. “So I immediately told him right there he was done for the day.”

The next morning, a trainer from the school called Connie and suggested she take Nathan to see a doctor. Connie took him to the Olathe Medical Center, where Nathan underwent a series of tests, including a CT scan. The doctors found nothing, Connie recalled.

“They said he was fine, probably had a concussion,” Connie said. “They told him ‘Take two [naproxen] in the morning and two at night and go see the doctor next week.'”

When he visited the family doctor the next week, Nathan confessed he was still having occasional headaches. So the doctor suggested he sit out another week. Seven days later, after Nathan passed a series of tests and said he was headache-free, the doctor cleared him to return to the field. But Nathan wouldn’t do so without the approval of his mother. “You need to be OK with this,” he said to her. “Are you OK with this?”

She wasn’t. Connie hadn’t wanted him to play in the first place. During his sophomore year, he broke his collarbone in a precarious spot under his neck that was a mere inches from severing an artery and potentially killing him. Then there was the broken hand. And now a concussion. Connie thought of a story Ron had told the children’s ministry one morning at church, in which God sends three boats to rescue a drowning man and the man refuses to get in all three boats, thinking God himself will save him. The man eventually drowns.

“I told him, ‘Nathan, this is your third boat,'” she recalled. “‘God sent you three boats. You’re going to drown. Don’t play. Just don’t play.'”

But Nathan insisted he was fine, and Connie didn’t see any abnormal behavior. Nathan was staying up late, finishing his homework and had just earned a 93 on a big calculus test. He wanted to finish the season with his friends. And with only two games remaining, one against Osawatomie, the other one-win team in the area, Connie assumed her son would be safe. So she reluctantly told him he could play.

On Friday, Oct. 22, Nathan returned to the field for Spring Hill’s game against undefeated Paola. Ron and Connie watched nervously in the stands as their son absorbed several hard hits, including one in the beginning of the game that they said noticeably stunned him.

“But after that game, all he said was how great he felt,” Ron said. “He was so happy. He said, ‘That was a lot of fun. They got me there for a minute, but I’m OK. I had a blast tonight.'”

‘I told him I would miss him’

The television in the surgical waiting room at the University of Kansas Medical Center was tuned to Home and Garden Television. Connie Stiles would have it no other way. Nathan had been airlifted from Osawatomie’s Lynn Dickey Field, and she and Ron had made the one-hour drive to the hospital, where doctors informed them their son’s brain was severely swollen and hemorrhaging. He would need four-hour emergency surgery to stop the bleeding, slow the swelling and, hopefully, save his life.

So while Nathan was in surgery, the easy-on-the-nerves home and garden network it would be. As the Stiles waited, friends, family and teachers began overflowing three hospital waiting rooms. At first, nurses urged the crowd to keep out of the hallway. But they eventually gave up. In each of the waiting rooms, crowds of people kneeled on the hospital floor, praying to God to save Nathan.

One hour into surgery, doctors realized their task was impossible. Nathan’s brain was so swollen that it had stopped telling his heart and lungs what to do. He had been living on 50 percent oxygen for as long as two hours. Even if he were to live, his life would never be the same.

The doctors told the Stiles family there was nothing more they could do. “It’s in God’s hands now,” one surgeon said.

“The news started out bad and got worse,” Ron said. “I knew it was serious. But I never imagined I’d be driving home with a dead son.

“But no matter what we said or what we did, it didn’t matter. God was calling him home.”

Not everyone accepted Nathan’s fate as easily. Ron said he had never seen the family’s pastor, Laurie Johnston, so upset.

“She thought we were going to pray that boy back to life,” he said.

Said Johnston: “I was mad. I was angry. Here I was, the shepherd of their family, and I couldn’t protect their sheep. To me, this wasn’t going to happen. I wouldn’t let it happen. Not Nathan. Not someone who had so much left to give this world. But at some point I realized, it was out of my control.”

As the clock crept past 2 in the morning on Oct. 29, Nathan was still alive. But his future was bleak. Ron and Connie decided it was time to start saying goodbye. They made the decision to allow each of Nathan’s friends go in to his room in groups of four to do just that.

It took almost an hour and a half. With each group, Nathan slipped farther and farther away. Just before 4 a.m., the last group walked in. They were Nathan’s closest friends.

“When I saw him

I just saw him earlier that day,” said Kahn, who kicked for Spring Hill and also played on the soccer team. “The last thing he ever said to me was ‘Win state.’ But seeing him in that bed

my best friend

looking like that

I told him I would miss him. And basketball wouldn’t be the same.”

Handling the grief and the guilt

Handling the grief and the guilt

The morning Nathan died, the phone rang in the office of Gary French, the superintendent for the Osawatomie School District. It was Ron Stiles.

“I was a bit nervous when it was him,” French said. “I had no idea what to expect.”

But Stiles wasn’t calling to complain, criticize or do anything else negative. He called to say “thank you” for the way Osawatomie handled his son’s crisis. He asked how the kids and the coaches were doing and if there was anything he could do.

“Here this man had just lost his son and he was worried about everybody else,” French said. “It was an amazing display of faith and humanity. It was inspirational.”

A day later, when word got back to Stiles that some of the Osawatomie kids were teasing one of the football players, calling him a “murderer” because of one play in which they thought he had collided with Nathan (he hadn’t), Stiles called French again.

“He told me he had heard what was going on and wasn’t going to stand for it,” French said. “What could he do? Could he call the boy? Did he need to drive down? He wanted to talk to the kid.”

Within 15 minutes Stiles was on the phone with the player, telling him Nathan’s death wasn’t his fault. It wasn’t anybody’s fault.

In the three weeks since their son died, the Stiles family has spread that message to anyone and everyone who will listen. In a statement broadcast on each of the Kansas City television affiliates, Ron said, “We absolutely do not hold any bitterness to anyone for what happened.” He added that there will be no lawsuits. What happened to his son will be determined “by doctors and not lawyers.”

Everywhere they’ve gone since that night, Ron, 55, and Connie, 48, have tried to spread this message: to Nathan’s coaches, his teammates, his friends, a member of the officiating crew that night and even his girlfriend, whom the Stiles said battled feelings of guilt after not sharing that Nathan had felt dizzy one day after working out.

“My daughter told me that she was pretty much headed the wrong way with all of this,” said Susan Swope, the mother of Courtney Swope, Nathan’s girlfriend. “But when you see the way the Stiles have handled it you can’t help but do everything within your power to stay strong.”

Connie also met for an hour with the family physician who had cleared Nathan to play. The doctor declined to speak with ESPN for this story.

“He felt horrible,” Connie said. “He was in tears. He felt so bad. He told me he kept going through everything over and over and over and he didn’t see anything he would have done differently. He told me he had lost his faith in medicine.

“I said, ‘Please don’t feel that way. It’s not your fault. You’re a good doctor. We need more doctors like you.'”

Ron and Connie also met with some 25 members of the Osawatomie football team who showed up at a ceremony to remember Nathan. The parents explained to the tear-filled teenagers that the entire night was crazy, none of it made sense. Not the eye-popping 99-72 final score of the game, more points than the two teams had tallied in their previous 19 games combined. And certainly not what happened to Nathan. It wasn’t their fault, the Stiles insisted. Football did not kill Nathan. But the kids couldn’t stop crying. So Ron pointed to a giant picture of his son in the front of the room.

“I told them, ‘You see that smile my son has on his face?'” Ron said. “I want to see that exact same smile on every one of your faces right now.”

People in the community have marveled at the way the Stiles have handled this tragedy. But for them, it’s the only way. By telling everyone else that they don’t believe this tragedy is anyone’s fault, they’re telling themselves the same thing.

Because of course there are questions. Ron and Connie constantly replay the nightmare in their heads, wondering what went wrong. A couple of days after Nathan’s death, Ron was looking through his son’s car and found a piece of paper lying on the floor in front of the passenger’s seat. It was a concussion management handout the family doctor had handed Nathan after clearing him to play.

“I saw that and I just thought, ‘Oh, Nathan; oh, no,'” Ron said.

Was Nathan having headaches the entire time and didn’t tell anyone? Did he suffer a brain hemorrhage after the initial concussion? If he did, why didn’t that show up on his CT scan? What about the hard hits he took in the Paola game? Did that play a role in any of this? That night in the hospital, doctors explained to the Stiles that the location where Nathan was hemorrhaging was an “old bleed,” meaning it was a spot where the brain had bled previously.

“One of the doctors said he didn’t think we could just blame it on the CT scan, that they didn’t catch it or whatever,” Connie said. “And so I made the comment, ‘Do you mean I could have just found him dead in bed one morning?’ And he said ‘Yes.'”

The answers won’t come until the medical examiner releases the autopsy report and the official cause of death in the coming weeks. In addition, sports concussion expert Dr. Robert Cantu and his researchers from Boston University and the Sports Legacy Institute will be reviewing Nathan’s case and will share their findings with the family. Cantu has authored more than 325 scientific publications and 22 books on neurology and sports medicine, including a September article in the Journal of Neurotrauma about second-impact syndrome and small subdural hematomas, or brain bleeds. Though he had yet to review Nathan’s CT scan or paperwork, Cantu said last week that the case “had all the earmarks” of a brain bleed caused by second-impact syndrome.

But for now, we just don’t know. It’s possible that what happened that night had nothing to do with Nathan’s previous concussion. Or he might have suffered from a brain-related problem completely unrelated to football.

Just last week, Connie came across a magazine story that suggested anyone suffering from a brain injury shouldn’t take any non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications because they might complicate clotting. Connie had found a nearly empty bottle of an over-the-counter anti-inflammatory shortly after Nathan’s death. Should he not have been taking it? Should she have put her foot down that day in the doctor’s office and told him no, he couldn’t play? Would it have even mattered? And what about Nathan’s role in all of this? Was he hiding something?

“Even if he was, what kid thinks, ‘Oh, I’m going to die from a headache?'” Connie said. “He’s a 17-year-old kid. They don’t think they’re going to die from anything.”

For now, Ron is trying desperately to shift his family’s energy and focus from “what if?” to “what now?” This past Saturday, he stood in front of the congregation at Hillsdale Presbyterian Church, held Connie’s magazine with the article about brain injuries in his hand and tossed it in a garbage can.

“That isn’t what we want to be about,” he said.

A life frozen in time

In the bed where Nathan used to sleep, the sheets still rest in the same position in which he left them that morning when he climbed out of bed and headed for school.

The shirts in his closet are organized by color. On his desk, a neon green cup has a drop of water on the bottom. And on a shelf at the foot of his bed, the purple and white crown of the homecoming king sits, its gold sequins changing the direction they shine depending on the light of day.

The room tells the story of a life frozen in time and a family that has been left trying to make sense of it all. According to the National Center for Catastrophic Sports Injury Research, 1.8 million Americans play football each year. And Nathan is the only one this season who is believed to have died from a football-related injury. Essentially, he is a statistical anomaly.

But tell that to Ron, Connie and his younger sister Natalie, who now live in a home without the plodding feet and shower singing of their son and brother. Tell that to the elderly ladies at Hillsdale Presbyterian, who miss Nathan’s arms wrapping around them every Sunday morning. And tell that to the not-so-popular kids at Spring Hill High, whom Nathan would say hello to and stand up for as if they were the most popular kids in school.

“I’m not convinced that he wasn’t some sort of angel,” Coach Orrick said. “I know people will have a hard time believing that, but when you look at the type of person he was you can’t help but ask ‘How can I better myself?’

“I’m not sure Nate wasn’t put here on earth to do just that — to change a lot of us for the better.”

To try to make sense of it all, to give them a reason to get out of bed each morning, the Stiles have dedicated themselves to making sure their son doesn’t die without a purpose. They fulfilled Nathan’s wish, allowing the donation of his bone and tissue to those in need. But beyond that, and beyond working with doctors and researchers to determine exactly what went wrong, they’re committed to achieving one of Nathan’s lifelong goals: helping his friends find God.

Nathan, who would have turned 18 on Nov. 2, had often talked with his mom about the concerns he had for his friends who were choosing the wrong path and how he wished he could somehow get them to ask life’s biggest questions. And so the Saturday morning after Nathan’s death, Connie was lying in bed when the idea hit her: The Nathan Project.

Instead of flowers or donations to fight cancer or feed the needy, Ron and Connie have used the money they received after Nathan’s death — more than $14,000 — to purchase study Bibles. And they’ve given those Bibles to anyone who will dedicate themselves to one year of Bible study. Faith, denomination, previous beliefs; none of it matters. They just wanted to people to explore and learn about God — for Nathan.

“I had to make sense of this insanity,” Connie said. “I had to give myself a reason this happened and do something. Otherwise I was just going to wither away and die.”

One week after Nathan’s death, at the ceremony attended by the Osawatomie football team and some 3,000 others, a stack of 1,000 Bibles lined the back of the Spring Hill gym. And after Nathan’s coaches, teachers and family spoke, after his mom sang and his band mates played a Christian rock song he helped write, Johnston, the pastor, invited anyone in attendance to grab a Bible.

Within a few minutes, two lines four to five people wide stretched the entire length of the Spring Hill gym. Nearly 650 Bibles were given out that night. Since then, the project has spread to other towns and gradually, other states. Ron Stiles has started a Facebook account, and he encourages people to reach out to him if they need somebody to talk to.

And at every Nathan Project event, Ron — who has size 10 feet — wears his son’s black Nike high-tops.

Size 12.

“I’m never going to fill those shoes,” he said. “But I’m going to do everything I can to walk in them.”

Wayne Drehs is a senior writer for ESPN.com. He can be reached at [email protected]. To find out more about The Nathan Project, visit Hillsdale Presbyterian’s web site, or search “The Nathan Project” on Facebook.