Ryan Covey grew up in Methuen, Massachusetts. He was an outstanding student, a talented athlete, a loving friend, and a doting cousin with aspirations of serving in the Marines. In 2006, Covey was assaulted while skateboarding and suffered a brain bleed. The next 14 years of his life were characterized by a litany of mental health issues, another significant brain injury, and dozens of psychiatric hospitalizations. On February 3, 2020, Covey died by suicide at age 31. His parents, Ron and Shela Covey, donated his brain for research after his death. Researchers at the UNITE Brain Bank did not find CTE but did find significant damage to Ryan’s frontal lobe. The Coveys are sharing Ryan’s story to show how much his brain injuries took from him and to raise awareness of the effects of concussion and other brain injuries.

Warning: This story contains mentions of suicide and may be triggering to some readers.

As a kid, Ryan Covey was either naturally good at something or worked relentlessly to become good at it.

Ryan was extremely bright. He excelled in math and science classes his whole life in Methuen, Massachusetts. He took the SATs in seventh grade and nearly scored a 1300. He was accepted into Norwich University’s future leadership camp in his junior year of high school and planned to attend the school after graduating.

Ryan had a creative mind and loved to build things. His father, Ron Covey, remembers Ryan building incredible works out of popsicle sticks and being a maestro with his Etch-a-Sketch. Ryan had dreams of serving in the Marines Special Operations Command and then an architect.

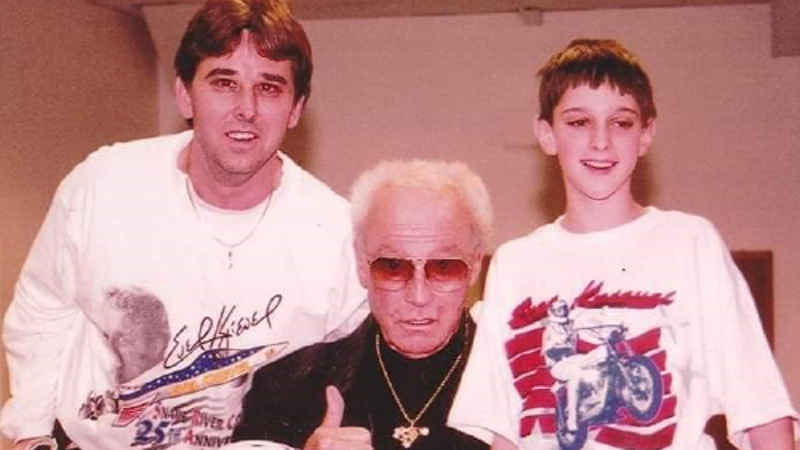

Ryan always succeeded in sports and competition. He began with t-ball, then ventured into basketball, then started playing tackle football at age 9. He and his grandfather were members of the Methuen Rod and Gun Club and Ryan was Massachusetts’ co-junior champion trap shooter in 2006. Ron grew up idolizing Evel Knievel and took Ryan to see Evel when Ryan was 12. The apple didn’t fall far from the tree, as Ryan was magnetized to skateboarding and snowboarding.

But above all, Ryan Covey was naturally kind. Ryan came home with a “Star Citizen” award from school too many times to count. He was a fiercely loyal friend. He cherished his brother Timothy and his mother Caryn. He taught his younger cousins how to do all the things he could do.

“He was a beautiful person,” said Ron.

Because of Ryan’s gifts and work ethic, Ron felt his son’s dreams were more inevitable than they were aspirational. But everything came to a screeching halt in February 2006.

Ryan was skateboarding one afternoon during his junior year of high school. A passing driver stopped, left their vehicle, and assaulted Ryan. Doctors found Ryan had a broken nose and a CT scan discovered he also had a brain bleed.

Ryan missed some school to rehab from reconstructive surgery from the injury. When he first returned to school, he was his usual, reserved self. But about six weeks following the assault, Ryan’s ROTC instructor observed him in the school hallways singing, moonwalking, and behaving bizarrely. Ryan became very paranoid about another attack. His cognitive abilities plummeted. He had a psychotic break in late March of 2006.

“It was difficult for him to hook up a DVD player,” said Ron. “It was awful. It was odd. Everything was different.”

Out of concern, Ron admitted Ryan to the hospital, where he was prescribed psychiatric medications for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Ron estimates that hospital stay was the first of more than 40 hospitalizations for psychiatric issues over the next 14 years.

Ryan’s new behavioral and cognitive problems made school, where he had always thrived, extremely difficult. His acumen and work ethic had him way ahead in credits to graduate high school. But obtaining his final credits in an English class became an odyssey over his senior year.

Shela Covey, Ryan’s stepmother, came into Ryan’s life a few months after the assault. She helped Ryan persevere through high school and the two of them developed an extremely close relationship.

After graduating from Methuen High School in 2007, Ryan attended UMass Lowell. He left college before he finished his first semester due to another psychotic break.

“He’d come over and give us hugs and sit with us, but he couldn’t really have conversation. We’d kind of just talk at him,” said Shela. “It was awful.”

Ryan was admitted to Arbour Hospital, a mental health hospital in Jamaica Plain, Massachusetts, over the holidays in 2007. There, he was diagnosed with Schizoaffective disorder and prescribed clozapine, an anti-psychotic. The new medication helped him stabilize and function again.

During the years following the 2006 assault, Ryan began experimenting with drugs. In 2012, he was believed to be on an extremely high dose of cold medicine and suffered another massive crash while attempting to skateboard down a steep hill near his apartment. Ryan spent days in the ICU being treated for swelling in his brain. He was eventually discharged without any definitive diagnosis of concussion or TBI. Ron and Shela say the 2012 crash precipitated even more drastic changes in Ryan than the 2006 assault did.

“It was a complete game-changer,” Shela said. “His personality changed. Everything changed. He became very withdrawn and upset that he couldn’t do the things he wanted to do.”

After the crash, Ryan stopped taking his anti-psychotic medication. His drug use accelerated. His core group of friends distanced themselves from him. In search of a new community that would accept him, Ryan surrounded himself with new, strange people. Ron and Shela say the new people were not his friends, rather people who used Ryan’s generosity – and his apartment – so they could use drugs behind closed doors.

“He couldn’t understand that,” said Ron. “He couldn’t see the forest through the trees.”

In 2014, a psychiatrist in Andover, Massachusetts was caring for Ryan when he suggested Ryan undergo a functional MRI to assess for brain damage. Until then, Ron and Shela assumed Ryan’s problems were stemmed from his own mental illness, as Ryan had a family history of mental illness. But the psychiatrist was the first person to associate his issues with brain injuries, and suggested Ryan participate in clinical research for brain trauma patients.

The suggestion caused Ron and Shela to ask Ryan about his concussion history. Ron knew of one diagnosed concussion Ryan suffered playing football. But he also skateboarded and snowboarded, so maybe three or four in total, they guessed.

Ryan chuckled at the estimate, leading Ron and Shela to assume he had suffered many more concussions in his life. Ron believes his son, who never quit anything before he had mastered it, could have tried and failed skateboard tricks hundreds of times, usually without wearing a helmet.

For the next five years, Ryan was in and out of various institutions. Mental health facilities in Massachusetts helped him find jobs for brief periods of time, but his impulsive behavior frequently cost him employment.

Ryan’s waywardness continued until it came to a head in June 2019. He was arrested following an altercation with Methuen police after he tried to steal a police cruiser. He was believed to be on drugs during the incident.

The resulting court appearance concluded with a judge ordering Ryan to stay off drugs and alcohol. Ryan diligently followed the orders and the sobriety brought him some long-lost clarity.

“I really got to know Ryan for Ryan,” said Shela. “Because there weren’t all the drugs interfering with his personality.”

Ryan was clean but still not mentally healthy. He was constantly, painfully anxious. He talked openly with Shela about the pain he was in, including thoughts of suicide.

Ron describes Ryan’s 31st birthday on September 28, 2019, as “horrible”. While out to dinner with family, Ryan couldn’t sit still and rocked back and forth violently. He was later admitted to the hospital from an anxiety attack.

“That one pulls at my heart strings,” said Ron of that birthday dinner. “That was an extremely helpless feeling for me. He was tormented.”

On February 3, 2020, Ron went to pick Ryan up so they could go get haircuts. When Ron entered the apartment, he found Ryan dead. Authorities ruled his death a suicide. Toxicology reports concluded Ryan was drug-free at the time of his death.

In their anguish over the next 24 hours, Ron and Shela remembered Ryan’s psychiatrist suggesting CTE in 2014. They called the UNITE Brain Bank and donated Ryan’s brain for research.

“It’s helping the study and the future,” said Ron Covey to the Eagle Tribune after he donated Ryan’s brain. “My son would have loved that.”

Researchers at the Brain Bank did not find evidence of CTE in Ryan’s brain. They did, however, find significant damage to Ryan’s frontal lobe. The damage helped explain Ryan’s behavioral changes, impulsivity, loss of reasoning skills, and diminished cognitive abilities over his last 14 years.

Ron hopes Ryan’s diagnosis will help those who wrote him off as a drug addict understand him differently. He knows Ryan may have been bound to suffer from mental illness at some point in his life. But he believes the 2006 assault completely altered the trajectory of his son’s life.

“He would have been that brilliant, smart kid,” said Ron. “He would have made a fantastic father. Because he was so good with kids.”

Thinking back, Ron and Shela both wish they knew more about the potential effects of brain injury. It wasn’t until after Ryan’s death that they ever heard of Post-Concussion Syndrome or considered the extent to which Ryan’s head trauma may have impacted him. They hope his story can be a gift to other families who are navigating the same waters they did.

“There has to be more out there about traumatic brain injury, not just CTE,” said Shela. “CTE is a good jumping off point that makes people perk up and listen, but brain injuries should not be ignored.”

The prevailing word Ron and Shela use when describing Ryan is love. They remember Ryan’s deep love for his family – extending to Ron, his brother, his cousins, and to Shela and her children. And they loved Ryan, unequivocally.

“I know that he knows that I loved him more than anything,” said Ron.

Suicide is preventable and help is available. If you are concerned that someone in your life may be suicidal, the five #BeThe1To steps are simple actions anyone can take to help someone in crisis. If you are struggling to cope and would like some emotional support, call the 988 Lifeline at 988 to connect with a trained counselor. It’s free, confidential, and available to everyone in the United States. You do not have to be suicidal to call.

Are you or someone you know struggling with lingering concussion symptoms? We support patients and families through the CLF HelpLine, providing personalized help to those struggling with the outcomes of brain injury. Submit your request today and a dedicated member of the Concussion Legacy Foundation team will be happy to assist you.

This story adheres to the Recommendations for Reporting on Suicide from reportingonsuicide.org