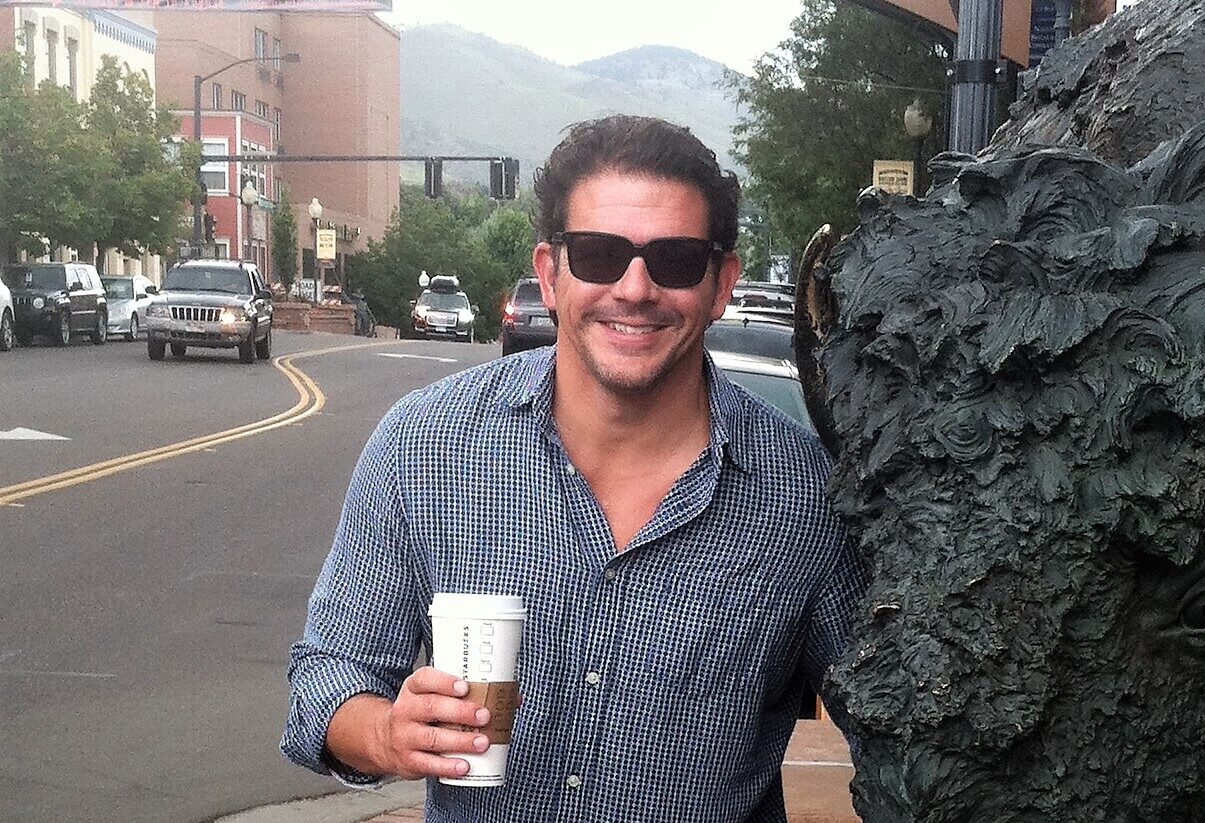

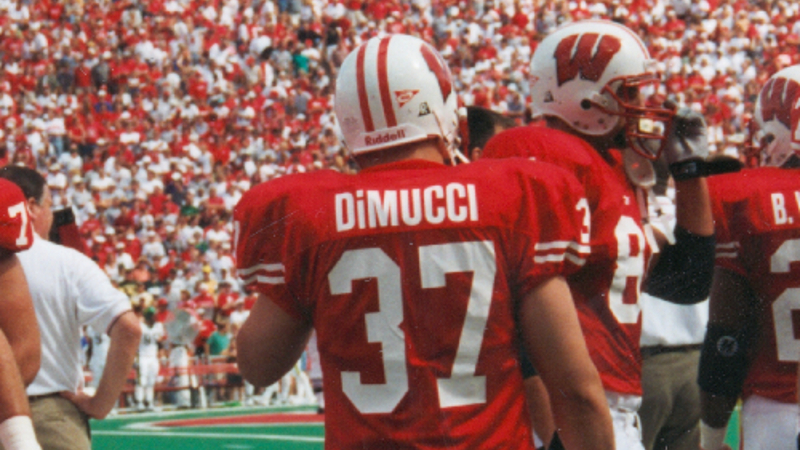

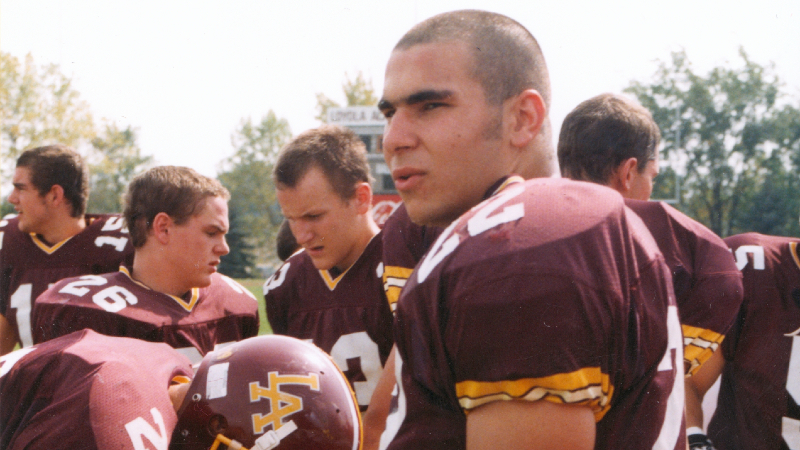

Salvatore “Sal” DiMucci was a talented football player who played from the time he was young through playing fullback for the University of Wisconsin. DiMucci stepped away after two years of playing due to knee injuries. In his early adulthood, DiMucci began having issues with his memory and concentration. In 2015, DiMucci told his wife Lisa he wanted to donate his brain to the Boston University CTE Center for research. DiMucci passed away in 2016 after an auto accident. Researchers at the Boston University CTE Center diagnosed him with stage 1 (of 4) Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE). Lisa DiMucci chose to share her husband’s story so others can know the risks of youth tackle football.

I never thought I’d be sitting at home reliving my late husband’s life through a box of newspaper clippings with two babies to look after. But there I was, less than a year after Sal’s death, thumbing through the mementos he kept boxed up. I used to think of the boxes as kind of a nuisance, taking up space. I didn’t understand why he’d kept so many. But then I came across his football boxes. There was a box of letters from college recruiters, a box of team photos and clippings of old articles from his college and high school playing days that showed him in the limelight as a star running back. It looked like an amazing time in his life filled with close friends, football scouts, and college scholarships. Those were his glory days.

I also never thought I’d hear a police officer pounding on my door. “Your husband has been in an accident, I need to take you to the hospital,” he told me. I sat alone in the hospital room for hours waiting for family and friends to join me, numb to what was happening and waiting to hear about my husband’s condition or if he was even alive. Part of me knew that he wasn’t. In the eight years that I’d known Sal he was never the type to drink and drive, but the toxicology report later confirmed that Sal was over the legal limit. Sal was driving home from dinner when he struck a tree and was thrown from the car; his two acquaintances walked away with minor injuries. I couldn’t make sense of the accident, or his risky behavior. I still can’t. Not completely.

Sal was strong and intelligent. He played two years of football at Wisconsin before retiring because he blew out both knees. For him to continue playing, his life would have revolved around cortisone injections and pain killers. He just didn’t want to start down that path to play football. Sal didn’t want his football career to destroy his body, so he walked away. He knew enough about his joints to decide football wasn’t worth destroying them, but he had no idea what football could do to his brain.

I met Sal in 2008, when he was 27. I was in medical school and he was contemplating sitting for the LSAT and applying for law school. As our relationship continued, he started to tell me that he felt like something was wrong with his brain. He would also say he felt like he was going to die young. I heard him, but I didn’t really listen until much later. I just thought he felt that way because he’d lost his own father to a heart attack when he was only sixteen. And neither of us knew enough about brain injuries, let alone chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), to understand what might be going on with him.

We dated off and on until we finished professional school, and he was still functioning at a high level. High enough to finish law school and to work in an important role at his family business. When we married in 2013 and had a baby on the way, Sal became more serious than ever about his suspicion that he had brain damage. Sal told me something was wrong with his memory and concentration, and I could see that he was struggling with his moods and behavior. He read everything that he could get his hands on about brain trauma associated with football, but he had come to rely on ADHD medication to concentrate. He hated that he had to take Adderall to accomplish simple tasks, but by that point he needed it get anything done.

Sal’s symptoms gradually got worse. His moods swung high and low, almost like bi-polar disorder. He struggled more with substance abuse issues as time went on. I couldn’t understand the changes, or why one minute he would be normal and then the next he’d be depressed and getting wasted, seemingly without reason. “I think better,” I remember hearing him explain. In the moment, while I was trying to raise a baby, manage a household, and deal with this man who would be fine sometimes and then completely off at other times, I was not able to process all the changes. But in hindsight, his words make more sense. Sal knew his brain was damaged, and he was trying to cope.

One night in April of 2015, Sal and I had been working on our estate planning and he’d taken Adderall to finalize our plan. He continued working after I went to sleep, and I vividly remember Sal bursting into the room at two or three in the morning. “Lisa! – Leese – I want my brain donated to the Boston University CTE Center for research.” He practically yelled it. I wasn’t thrilled to be woken up that early in the morning, and he was disappointed by my response. He wanted and needed me to know. I didn’t fully understand why it meant so much to him.

Six months later, Sal and I went to see the film Concussion. That’s when things got real. Before that point I was starting to truly believe that something was wrong, but the movie drove it home. Sal was sobbing as we got into the car afterward and I felt like I got punched in the stomach. My mind raced. I’d seen the mothers and wives in the movie. What was my future going to look like with this man? If this is already what it’s like today, what is it going to look like ten or twenty years from now? What are our children going to see? Is it going to be like the scene in the movie where Justin Strzelczyk is screaming and raging at his family and terrifying his children? Is he going to be sitting there emotionally detached from life? Could this become my life?

Six months after that, I was picking out Sal’s casket in a funeral home. I was five months pregnant with an almost 2-year-old at home. I was numb, and struggling to process everything that was happening as I went through the motions. “Yes, those flowers are fine – yes, 3:00 PM for the wake – yes…wait…No. No. Where is Sal’s body? Hold on. No, I can’t pick out a casket. What’s happening? He wants his brain donated, I’m not doing anything until I know that his brain is going to be donated.” I wasn’t going to plan a funeral until I knew that his brain was going where it needed to go. So, I called my attorney, and the funeral director called Boston University.

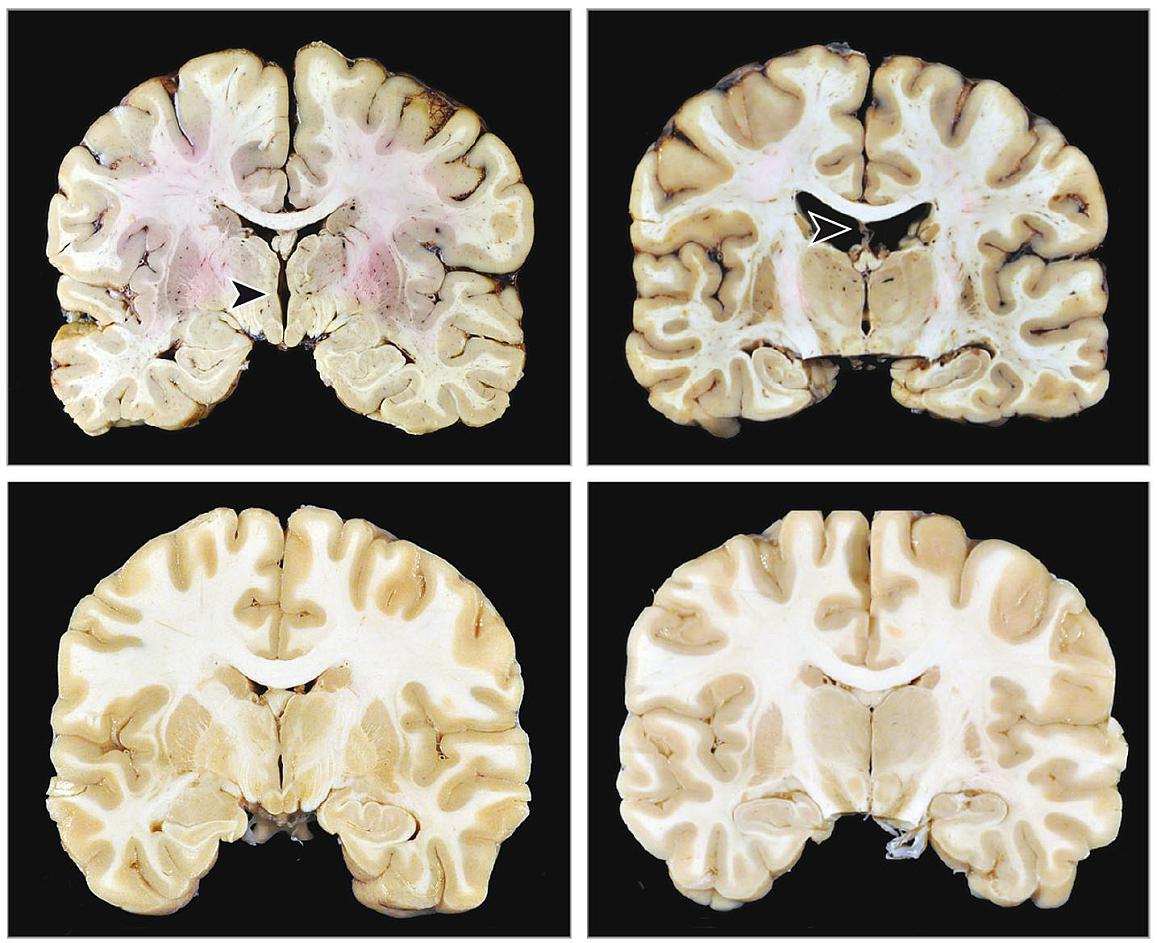

I was just as devastated getting the results of Sal’s stage one CTE diagnosis as I was when I heard about his death. I thought about what else I could have done. Could I have treated him differently? Could I have helped him manage his symptoms? Sometimes those thoughts return. Now, I think more about what I can do to help people recognize this disease in their loved ones so that they can find ways to treat the symptoms while they’re still alive. And I feel like I need to do something to help people understand that what happened to Sal’s brain could happen to their child’s brain.

I remember one specific moment when I was at the gym. I was sitting on the ground stretching and I heard two women behind me talking about their 10-year-olds’ summer football camp. I didn’t know who they were, but I almost lost it. I almost went up to them and shouted, “Why are your kids playing football? Don’t you know what can happen to them? Don’t you understand?” I fought the urge, deciding it wouldn’t have done any good. But in that moment I knew I had to do something more. I had to share our story with more people so that they could understand what’s at stake.

In the years before Sal’s death, he became passionate about protecting kids from head injury. He was adamant that football was the reason why he had mood swings and trouble concentrating, and he had no intention of letting our sons play. He researched and thought about investing in a company that was designing “soft” helmets to minimize impact. Sal said over and over that he used his head as a weapon, and that there was no getting around hits to the head. He’d recently found a passion for tennis, too. “If I had found a game like this sooner I wouldn’t be so messed up,” he would say, meaning he wished that he’d played tennis, paddle tennis, or some high-adrenaline sport as a kid instead of football. He fell in love with the idea of promoting non-contact sports. More than anything, Sal felt that there needs to be an option for the aggressive kid who wants to get out there and get his adrenaline pumping that doesn’t result in brain damage.

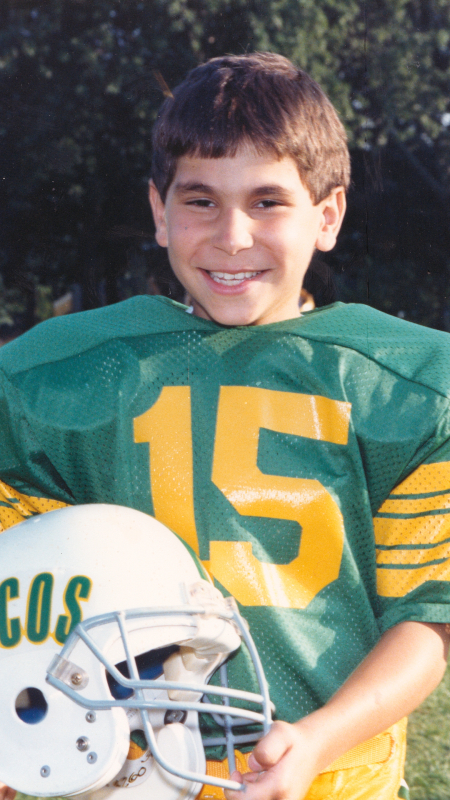

The most difficult moment of going through that football memory box was finding a photo of Sal in his football pads at eight years old. He was so young, and our sons Salvatore IV and Rocco look so much like he did. I get angry when I look at it. I’m angry at the absurdity of Sal developing a brain disease because of a glorified form of entertainment. I’m angry that there is a continuing cycle of football players who decide to enroll their young children in this sport because they don’t know any better. Sometimes I feel helpless to change it because this game is so embedded in our culture and lives.

When I drive by a football game, I see the lights, and I know that someone’s child is reliving the same glory days that my husband lived through. Then I can’t help but picture Sal a few years before he died, too depressed to get off the couch. Or having a fit because he can’t concentrate for long enough to complete a simple task. Or hyper-focused and almost crazed because he took an Adderall to knock a few things off his to-do list. I drive by and wonder, if those parents saw what football did to Sal, would they still cheer for their child to dig deep and finish the game out strong?

So many people want their child to become a star athlete, and I don’t blame them. But it’s obvious that something is wrong when that star could become a 30 or 40-year-old who is unable to function in society properly because of brain damage. Sports are meant to prepare children for their future, not endanger it. If this game is going to continue, something will have to change.