Tim Roberts was almost always the smallest player on the football field during his high school career in Illinois, but that never stopped him from playing with grit and determination. Well after his playing days were over, Tim’s family noticed changes in his behavior, including irritability, aggression, and problems with drinking — symptoms they suspected were due to CTE. Tim passed away from renal failure in 2022 at the age of 64. Tim’s family donated his brain to the UNITE Brain Bank, where, even though he only played football from age 8-18, researchers diagnosed him with the most advanced stage of CTE. Below, Tim’s family shares his Legacy Story to raise awareness around the risks of repetitive head injuries.

Warning: This story contains mentions of suicide that may be triggering to some readers.

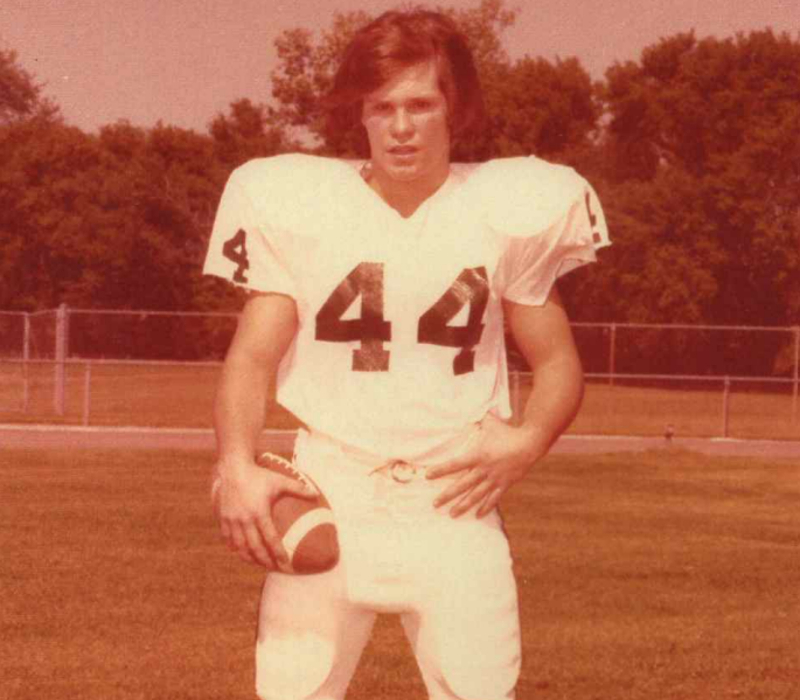

Tim Roberts was raised in Iowa and Illinois with three siblings. He began playing tackle football at age eight and rarely missed a practice. He was small compared to other football players but made up for it by being strong, fast, and aggressive. Tim continued to play through both junior high and high school in Elk Grove Village, Illinois, graduating in 1977.

Friday nights on the field with his teammates was Tim’s favorite place to be. He played on offense as a running back and on defense as a cornerback, almost never taking a break. He was all-conference and all-area for two consecutive years and an honorable mention for all-state. During his time playing football, Tim also experienced a handful of known concussions, one with complete loss of consciousness, along with many other hard hits. We know of one incident where he was unconscious after a play and left the field in an ambulance.

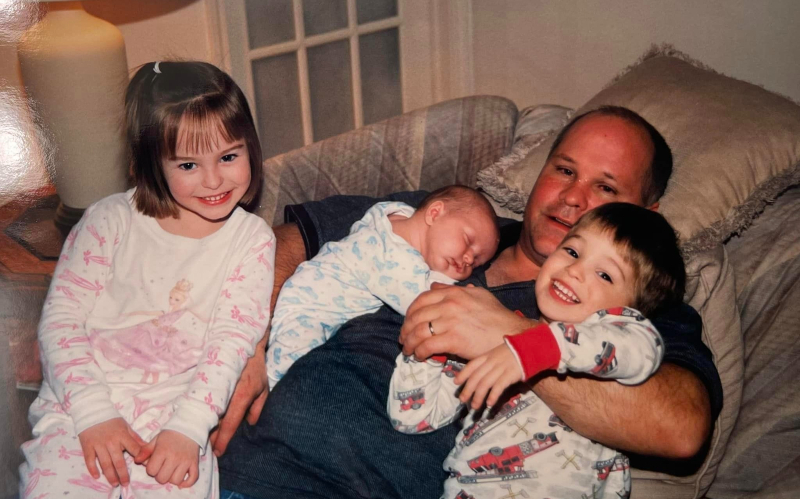

Tim was very social and made many friends in high school and college. He met his future wife, Liz, at the University of Tennessee. They were married in 1991 and had three children: Caroline, Thomas, and Jack. They were his absolute pride and joy. Because of them, Tim was generous, mischievous, and loved big family gatherings.

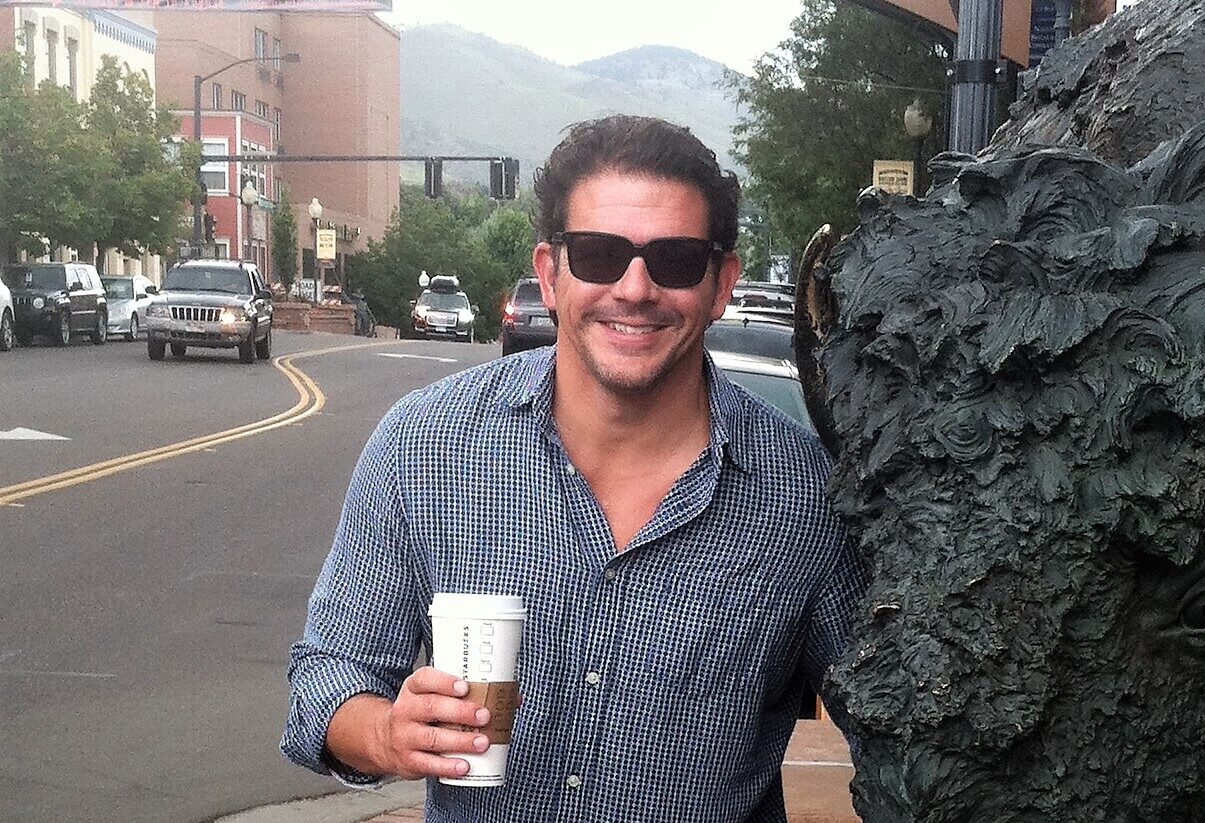

Intelligent and gifted at all things mechanical, Tim was an accomplished designer of custom manufacturing equipment. He also loved spending time boating, golfing, and was particularly fond of his dog, a husky named Nikki.

Unfortunately, over the years, we noticed several changes in Tim. He began to drink constantly and heavily, and he became short-tempered. Usually a terrific husband and father, he started to fail in that role, as well. On one particularly difficult weekend, things really fell apart. Tim threatened suicide, which alarmed our family, and several of us responded to help him.

As time went on, we became more alarmed about his alcohol abuse, aggression, and forgetfulness. His erratic behavior, combined with drinking, led to accidents, broken bones, and hospital stays. These difficulties cost him his marriage and damaged his relationships with his children. His world diminished, and he spent most of his final months with his devoted parents.

We suspected CTE even though he only played football through high school. We suggested it to his doctors, but none supported the idea.

Tim also developed renal failure secondary to a rare autoimmune disease approximately 20 years prior to his death. Eventually, he required dialysis and later a kidney transplant. Unfortunately, because of his inability to comply with medical advice, he was unable to receive a transplant. Eventually, Tim discontinued his sporadic dialysis treatment. Surrounded by family at the time of his death, Tim finally succumbed to the consequences of renal failure.

We decided to donate Tim’s brain to the UNITE Brain Bank, where Dr. Ann McKee diagnosed him with stage 4 (of 4) CTE. This is the first time CTE of this severity was found in someone who played only through high school. We had suspected CTE but were shocked and saddened to see how advanced it was. Tim paid a big price for playing football, across all aspects of his life.

We have since learned that Tim was the prototypical football player likely to develop CTE. He started playing at a young age, started on both offense and defense, was on the smaller side, and played to win.

The decision to donate a loved one’s brain to research is not taken lightly. We hope these findings increase awareness of the dangers of repetitive head injuries to athletes. We are so grateful to Dr. McKee, the BU CTE Center, and the Concussion Legacy Foundation for their ongoing research.