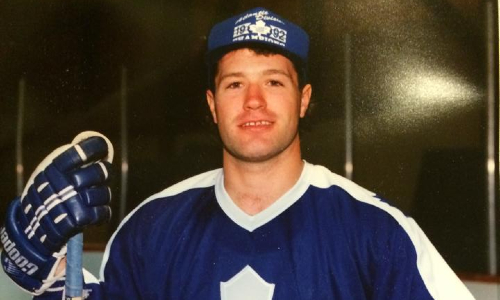

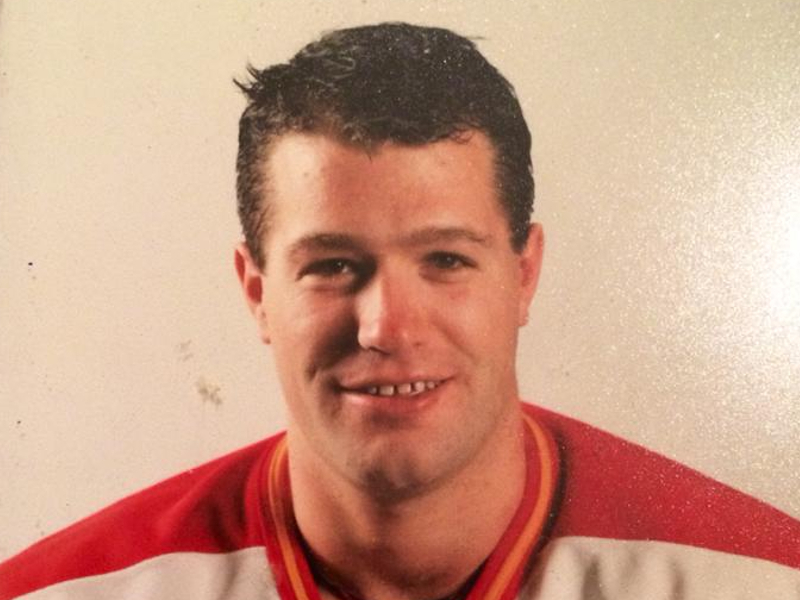

Todd Gillingham played the role of enforcer on the ice, but he was a kind and gentle person away from the rink. The more than 30 concussions and repetitive head trauma he endured during his hockey career, led to issues later in life, including battles with depression and substance abuse. After hearing of fellow hockey players who had gone too soon, Todd asked his family to donate his brain to research when he passed. They fulfilled his request upon his death in January 2023 at the age of 52. UNITE Brain Bank researchers at Boston University are currently studying Todd’s brain. Below, Todd’s sister Janice shares his Legacy Story.

Todd Gillingham had a quirky smile and a twinkle in his eye. He was the guy who lit up a room when he walked in. Todd was the life of a party and knew how to live each day to its fullest.

Growing up in Corner Brook, Newfoundland, Canada, Todd spent the summers of his youth on the baseball field, with cleats and bats giving way to skates and sticks during the winter months. He excelled at both sports but eventually turned his full attention to hockey, which he started playing around four years old. He was always the biggest guy on most teams, so expectations for him to excel were always high. But no problem for Todd — he surpassed them and much more.

Though Todd was big and could throw a hit, he would often give a shoutout to the smaller players prior to checking them. That’s the kind of guy he was. His dedication to hockey paid off at the age of 16, when he joined the Verdun Junior Canadiens of the Quebec Major Junior Hockey League (QMJHL).

Despite moving from his small Newfoundland home community (population 20,000) to a largely French-speaking suburb on the outskirts of Montreal, Todd immersed himself in the culture and taught himself French. This wasn’t surprising to those who knew him. Todd’s level of intelligence can be best exemplified during his senior year in high school, while still playing hockey in Quebec, when he returned home with six weeks left in the school year. His goal was to write his final exams and graduate with all the kids he grew up with. Mission accomplished.

From the moment Todd first stepped on the ice in the QMJHL, he developed a reputation as a rugged player. His hard-nosed approach to the game meant he was called upon to drop the gloves on a regular basis. By the time he ended his four-year career there, he had amassed 971 penalty minutes in just 265 games. And though he never wanted to be known as a fighter, Todd ultimately would do whatever it took if it meant achieving his goal of playing in the National Hockey League.

Unlike the prototypical hockey enforcer, Todd didn’t just excel with his fists. In his final year, he finished the regular season with 46 goals and a league-leading 102 assists in 66 games. His 148-point total ranked him second in the entire league behind teammate Yanic Perreault.

After his junior career came to an end, Todd spent 10 years in the minor professional ranks playing in Canada, the United States, and Wales. But most teams didn’t see him as a scorer or playmaker — they wanted him solely for his toughness and grit. So, he found himself trading punches for that decade with some of the strongest hockey players in the world.

For a burly guy with a reputation as a fighter on the ice, Todd was a calm, sensitive, and kind individual away from the rink. He would send flowers to his grandmother on special occasions, email his mom electronic greeting cards, and even sold old equipment to help finance his sister’s last year of university.

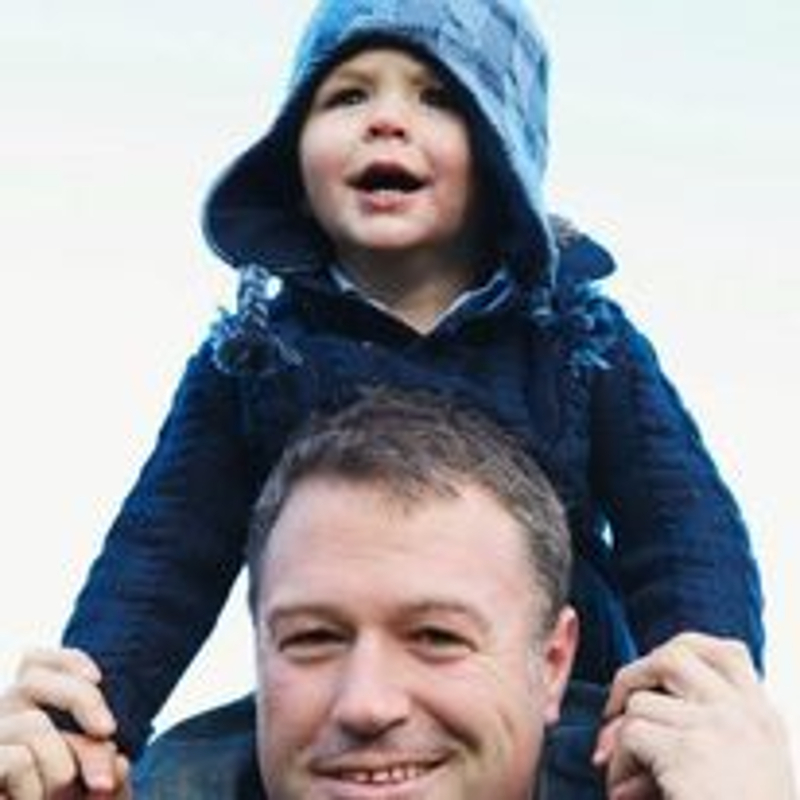

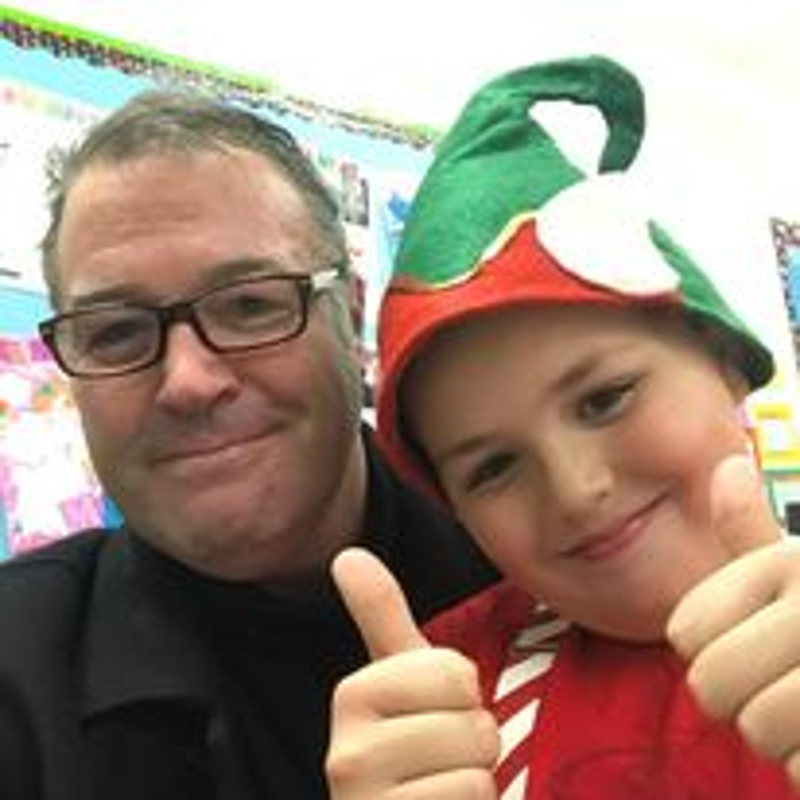

Once Todd finally decided to hang up his skates, he completed his degree and started a family. He put his post-hockey career on hold for a few years to help raise his children, before eventually acquiring a real estate license. He loved his family and was a terrific father, whether putting his daughter’s hair into ponytails and watching her play soccer, wrestling and playing chess with his son, or having the neighborhood kids over for a campfire. He really tried his best to be a good dad.

Todd was diagnosed with more than 30 concussions during his playing career, but it’s suspected the actual number of injuries was much higher. Oftentimes, blows to the head were dismissed, not diagnosed, or left untreated. No one is positive when he first started to show signs of concussion-related issues, but loved ones did notice a distinct change in behavior almost immediately after his playing career ended in 2001. He started partying heavily and living more carefree. And while he remained close to his family, Todd began to bottle his emotions. His family just assumed it was due to difficulty adjusting to life after hockey or struggling with the loss of his father when Todd was 24 years old.

Over the years, as cases of Post-Concussion Syndrome (PCS) among professional athletes became more widely known to the public, Todd began to suspect his mental health issues could be related to the multiple head injuries suffered during his career.

In 2017, Todd’s worries were confirmed.

After traveling to California for medical testing, scans detected several black spots on his brain, an indication that part of Todd’s brain was no longer functioning. Doctors suggested he learn new activities to help encourage brain plasticity and increase neural pathways, not unlike senior citizens who begin experiencing memory loss. Todd began taking piano lessons, doing yoga with his daughter, and even pruning small bonsai trees.

Still, his condition kept worsening.

Soon, Todd noticed seasonal changes directly impacted his emotional condition. He struggled to adjust and experienced increasing head pain. He was at his worst on nights when the moon was full. He tried using a sunlamp during the dark winter months to trick his brain into thinking it was light out and to help with serotonin regulation.

But it became too much for him to handle, and things began to fully unravel.

After being prescribed medication to treat symptoms of depression, Todd began self-medicating. The headaches that had become part of daily life were worse than ever. He battled substance abuse. His marriage failed, his career fell apart, and he ran afoul of the law. He spent countless hours sitting quietly, rubbing his head. His family tried to provide a support system but often felt helpless as they watched someone they loved turn into a completely unrecognizable person.

Todd then developed cataplexy, characterized by transient episodes of voluntary muscle weakness precipitated by intense emotions. He withdrew more from daily activity and cared less and less about living. He would ask if we thought he was a good dad and say how he ruined relationships with special people in his life.

Even during his struggles, Todd was aware of the brain issues that had claimed some of the lives of his hockey peers. In an online blog he wrote on October 18, 2011, titled “Warning Bells Are Ringing,” Todd addressed the recent deaths of former NHL enforcers Wade Belak, Rick Rypien, and Derek Boogaard. Belak and Rypien both took their own lives after battling chronic depression; Boogaard had passed away from an accidental overdose. All three had later been diagnosed with CTE.

Todd wrote: “My problem with all of this is that there is a far greater issue and problem slowly emerging that has not garnered anywhere (near) the amount of attention it deserves, and this problem, unlike the recent onslaught of head injuries and rule changes, has been around the game forever at all levels.

“This past summer three young men… who were playing or just recently retired lost their lives at very young ages, and I find it terribly disturbing how it seems to be all but forgotten. I can guarantee you one thing, that if these tragic deaths would have occurred to some of the game’s higher echelon players, there would have been a full investigation and research carried out by both the NHL and Hockey Canada, as to how and why these types of tragedies can occur to our players, and they would be quick to react and get some damage control done to protect the NHL’s and Hockey Canada’s pristine image.”

“Why do I believe this is the case? Because I have played the game at all levels and have experienced some of these mental health issues that these players have.”

Todd Gillingham died in an alleyway in downtown St. John’s, Newfoundland in the late afternoon hours of Jan. 14, 2023. He was 52 years old. While some speculated his mental health issues may have finally been too much for him to battle, his cause of death was determined to be the same heart condition that resulted in the untimely death of his father Cavin at the age of 46 in 1994.

Well before Todd passed away, he requested his family donate his brain to science in the hopes of finding answers to the question of why he was in so much pain during his final years. As he told them: “If I could go back in time, I would have given it (hockey) all up in exchange for a healthy brain and life.”

Ironically, Todd gave everything to the sport he loved, but the sport did not return the favor.