Tommy McDonald was a multi-sport star in New Mexico before attending Oklahoma University. McDonald went on to a Pro Football Hall of Fame career in the NFL and won the 1960 NFL Championship with the Philadelphia Eagles. After football, McDonald ran his own painting and plaque business in Philadelphia. In his 70’s, McDonald began experiencing issues with his memory and cognition. He died on September 24, 2018, at age 84. His brain was later studied at the UNITE Brain Bank, where Dr. Ann McKee diagnosed Stage 4 (of 4) Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE). McDonald’s son Chris and his daughter Tish spoke with CLF to share their father’s triumphant life story.

Tommy McDonald told anyone he could to follow their dreams – that anything was possible. He said it because he lived it.

McDonald was born in Roy, New Mexico in 1934. As a kid, McDonald was small but extremely quick. He would give his dad cash he won in footraces. Knowing his son had considerable talent but very little chance of getting noticed by college coaches in Roy, McDonald’s father moved the family to the bigger city of Albuquerque when McDonald late in his sophomore year of high school.

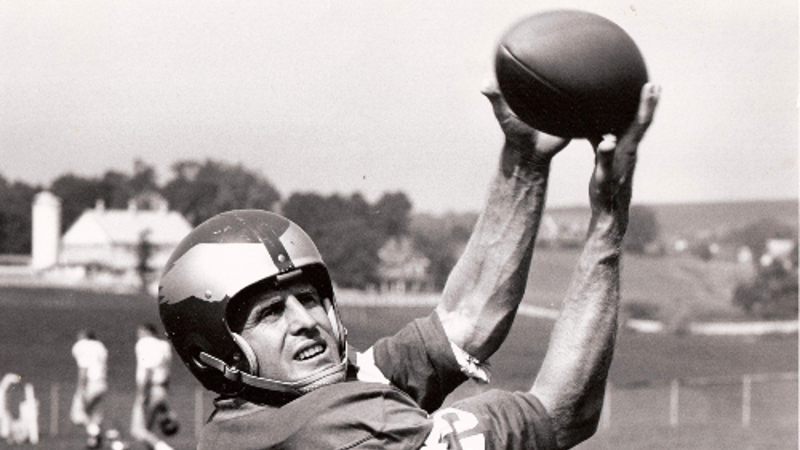

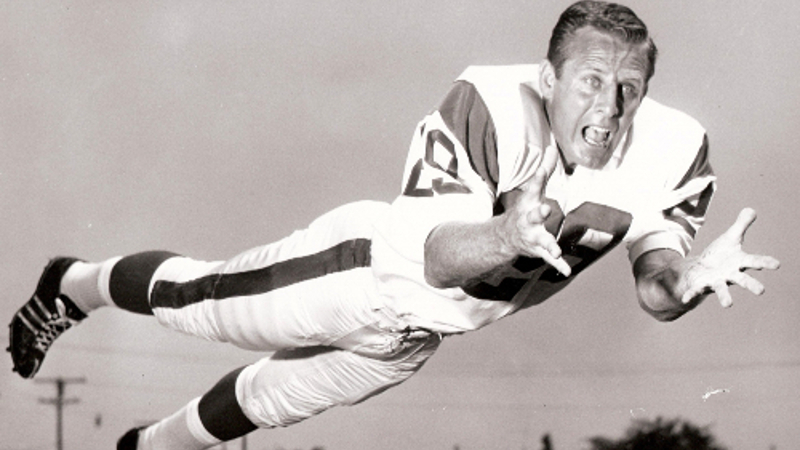

In an era without the assistance of high-tech receiver gloves, many pundits stated McDonald had the best hands in the NFL. McDonald appeared on the cover of Sports Illustrated in October 1962 with the caption “Football’s Best Hands.” But the statement applied to McDonald’s ability to catch footballs, not to the literal shape of his hands. In Albuquerque, McDonald’s father held Tommy back a grade to allow him to grow. In exchange for delaying his schooling, McDonald’s father supped up a motorbike for Tommy to ride around town with. One day, a car cut McDonald off while he was riding, leading his bike’s clutch to snap and completely sever a third of McDonald’s left thumb off.

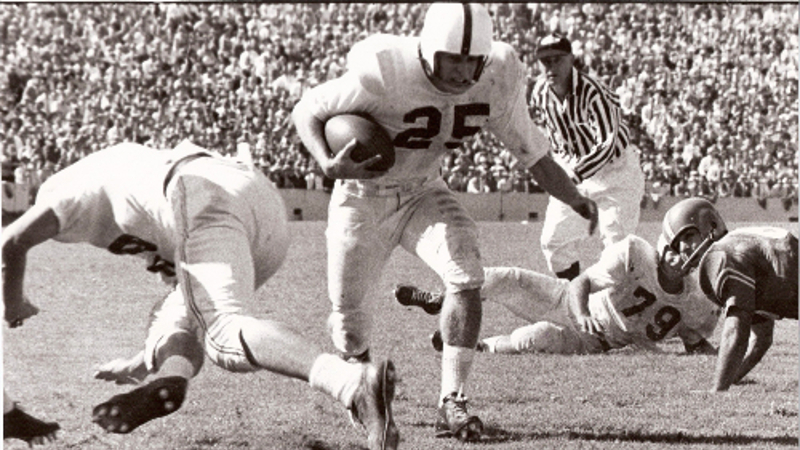

Despite that, McDonald dominated New Mexico athletics. He won five gold medals in the state track meet, set his city scoring record for basketball, and set the state scoring record for football as a running back. His exploits earned him a scholarship to play running back for Oklahoma University.

One could argue his career at Oklahoma was one of the best in college football history. In McDonald’s three seasons of varsity play in Norman, the Sooners never lost a game, winning two National Championships over the span. In 1956, McDonald finished third in Heisman voting and won the Maxwell Award, given to the best all-around player in the country.

In 1957, the Philadelphia Eagles drafted McDonald 31st overall in the NFL Draft. McDonald’s exuberance, grit, and production instantly connected him with the city of Philadelphia. When McDonald scored the first touchdown in the 1960 NFL Championship at a snowy Franklin Field, Eagles fans mobbed him in the corner of the endzone.

The Eagles beat the Green Bay Packers 17-13 that day. After the game, legendary Packers coach Vince Lombardi said, “If I had 11 Tommy McDonalds, I’d win a championship every year.”

One of McDonald’s trademarks was springing up quickly from the turf after big hits. Teammate Chuck Bednarik once accused McDonald of getting up too quickly after such hits. But at 5’9,” 175 pounds, McDonald used every tactic he could to convince opponents they could not get the best of him.

McDonald’s son Chris estimates his dad bounced up after a big hit and went back to the huddle following a concussion dozens of times.

There were some hits McDonald could not downplay. He told a story of getting knocked out cold in San Francisco and waking nearly 10 hours later in Philadelphia. Another time, a Dick Butkus hit left McDonald unconscious for more than a minute. He missed only two plays before returning to the game.

“If you looked like you were OK and your cobwebs were clearing, they sent you back in,” said Chris.

McDonald finished a decorated NFL career in 1968 as a member of the Cleveland Browns. He missed only three games in 12 seasons. At the time, a decade in the NFL still meant you would need to find a day job after retiring. His requited love for the people of Philadelphia led him to make the city of brotherly love his permanent home.

He lived outside of Philadelphia and ran an oil painting and plaque business. He and his wife Patricia had four children together. His boundless energy could have powered the stadium’s lights, leading Eagles’ brass to invite McDonald to countless games, team events, golf tournaments, and autograph signings. But after days full of smiling and posing for pictures, he loved nothing more than loading up the family car and going out to Chinese food in Philadelphia’s center city.

“He never bragged about his stats,” said McDonald’s daughter Tish. “He was just dad.”

Just dad became just grandpa. He loved attending his five grandchildren’s games, where he was famous for providing tips to the young players and infamous for pulling pranks on his fellow spectators.

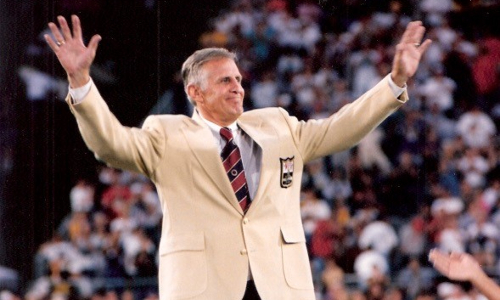

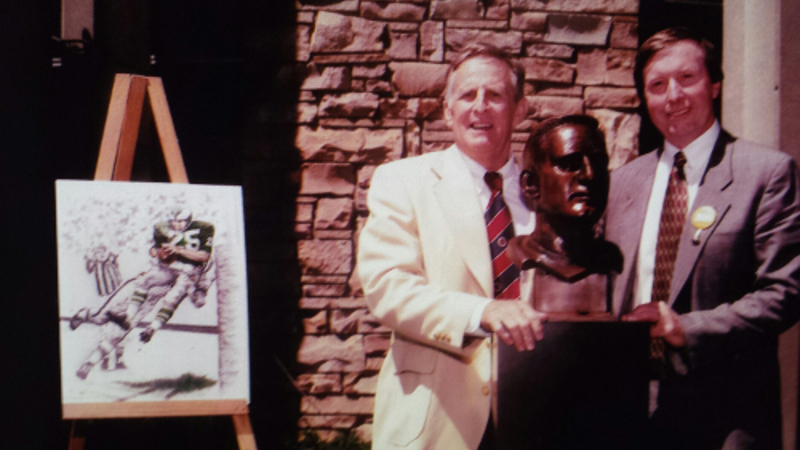

In the 1950s, a young Eagles superfan named Ray Didinger frequented Eagles’ training camp in Hershey, Pennsylvania with his family each summer. He delighted in getting to hold Tommy McDonald’s helmet and interact with his hero as the team walked on to the practice field. 40 years later, Didinger, then a decorated Philadelphia sportswriter, led a campaign to get McDonald inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame. In 1998, McDonald got a call he wondered if he would ever receive. He was to be enshrined in the Hall of Fame that summer.

After Didinger introduced McDonald to the audience in Canton, Chris and many of the family members expected McDonald to share his story of overcoming a small stature and a small town to inspire kids across the country to never give up on their dreams. McDonald went in a different direction. He cracked jokes, tossed his 35-pound Hall of Fame bust up in the air, played the Bee Gees’ “Stayin’ Alive” from a boombox, and chest-bumped all his fellow inductees.

Some members of McDonald’s family were surprised by Tommy’s speech. But for the same reasons he flung himself up from big hits as a player, McDonald explained to his family that his on-stage antics were a way to hide his pain.

By then, McDonald became emotional very easily. His father had passed away four years earlier and his mother was too ill to attend the ceremony. Having been extremely close with both parents, McDonald guessed he would unravel if he started talking about them in a conventional speech. He chose to keep it light instead.

McDonald’s emotionality was one of the first signs of change in his later years. His memory came next.

McDonald had driven the same route from his home in King of Prussia, Pennsylvania to Lincoln Financial Field in Philadelphia dozens of times a year for the past six decades.

But on his way back from a Philadelphia Eagles event in 2008, Tommy McDonald called his wife.

“The car could have been on autopilot, he’s been there for 50 plus years,” said Chris. “But he was totally lost.”

Whenever his memory failed him, McDonald, who never cursed, lamented about “these dang concussions.”

For most of his senior years, McDonald stayed active by playing tennis and racquetball. But McDonald’s cognitive issues escalated when he became more sedentary.

After his induction, McDonald eagerly returned to the Hall of Fame every summer. He loved the honor of being in football’s elite fraternity and enjoyed celebrating each year’s new class of honorees. But McDonald’s memory regressed to the point where returning to Canton provided too many opportunities where he could fail to remember someone’s name. He stopped going entirely.

“He didn’t trust his mind,” said Chris.

Outside of the bursts of emotion, the memory loss and the associated frustration, the McDonald family says Tommy maintained a positive spirit throughout his life. Chris and Tish remember him often saying, “I’m above the grass,” through a giant grin.

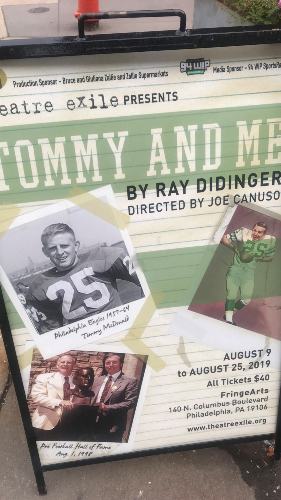

In 2015, Didinger produced a play, titled Tommy and Me. The play celebrated the odds McDonald overcame throughout his life and showed how McDonald made an indelible impact on Didinger’s life. The entire McDonald family attended the first reading of Tommy and Me. McDonald was delighted throughout the reading.

“That was my way of repaying him a little bit,” said Didinger in 2016.

As McDonald aged and his cognitive problems first emerged, Tish, Chris, and their siblings Sherry and Tom assisted with his care. Chris read news of other former NFL players suffering from Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE). The family heard from other football families about former players struggling in similar and different ways as Tommy. It led Chris to decide to donate his father’s brain to research after he died.

“If he could help another player out and make the game better and safer for today’s player,” said Chris. “Then he’s all for it.”

In the mid-2010’s, McDonald’s wife Patricia suddenly contracted Lewy bodies with dementia. She died on January 1, 2018. On the way back from her funeral, Tish remembers her father staring back at him, eyes agape. It was only then that he realized his wife of 55 years was gone.

“That was how bad it got,” said Chris. “He was really out of it.”

Eight months later, on September 24, 2018, Tommy McDonald passed away at age 84.

Chris followed through on brain donation and McDonald’s brain was studied first at the University of Pennsylvania then at the UNITE Brain Bank in Boston.

Tommy McDonald holds several amazing distinctions. He is the shortest player in the Pro Football Hall of Fame. He is one of the last players to play without a facemask. His Oklahoma Sooners’ winning streak of 31 games seems immortal. He holds the Eagles’ record for receiving yards in a game. Now, he is one of the many former NFL players to be diagnosed with CTE.

Dr. McKee, Director of the Brain Bank, diagnosed McDonald with Stage 4 (of 4) of the degenerative brain disease. She said McDonald’s brain pathology explained the massive memory loss he experienced in the last decade of life.

“What I found was classic for long-standing CTE,” Dr. McKee said in a 2021 interview with the Philadelphia Inquirer. “It had all the characteristic lesions around vessels involving a considerable extent of the brain.

For the McDonald family, the diagnosis confirmed what they had already come to realize: more than 20 seasons of football filled with dozens of concussions had done severe damage to Tommy’s brain. Just as proud as McDonald was each year to return to Canton, they are proud to help Tommy give back to the game he loved through CTE research.

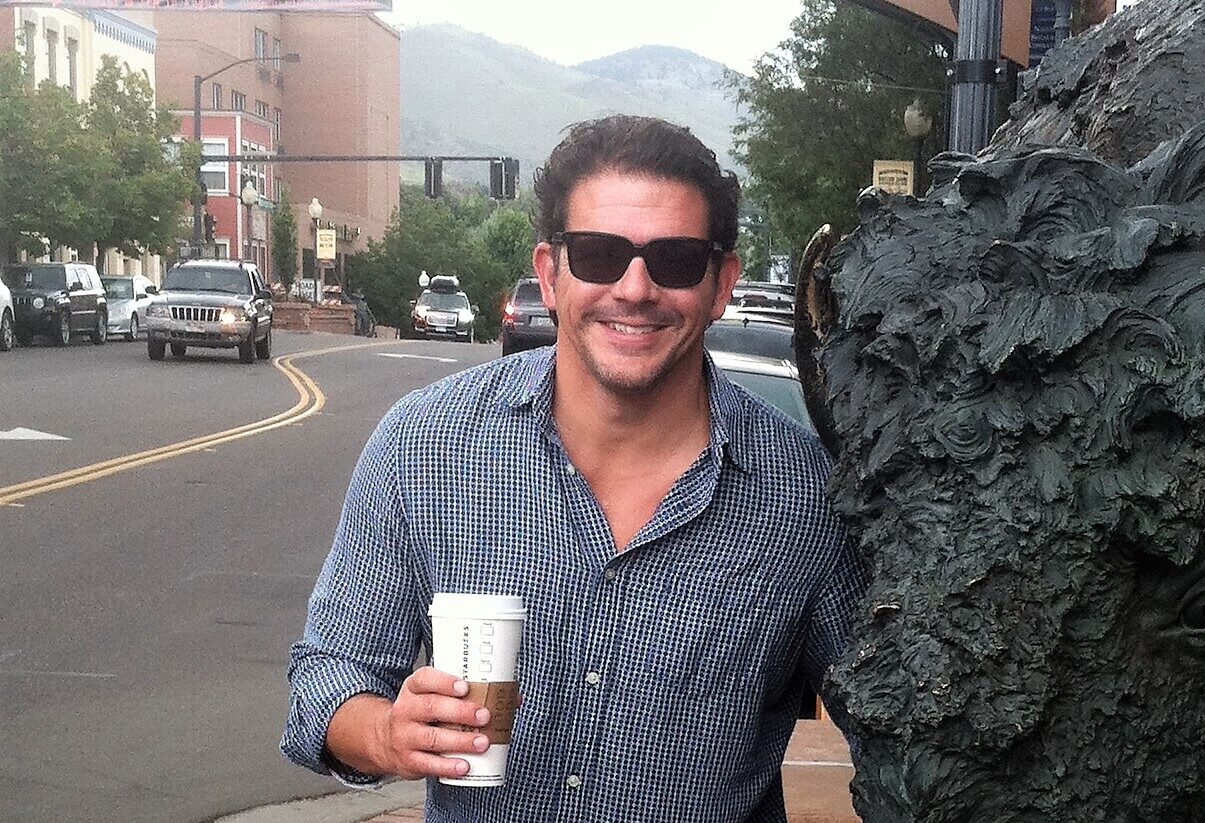

Chris and Tish believe their dad’s story of overcoming his size and circumstances, the story he didn’t tell at his Hall of Fame induction, is one anyone can take to heart.

“His number one thing would be to not let anybody tell you, ‘You can’t do it,’” said Chris of his father. “If you have a goal in life, stay determined and persevere.”

For other children of CTE, their message is to relish every moment you get with your parent.

“Enjoy every single day that he’s here, even if it’s a small percentage of him,” said Tish. “Because when they’re gone, they’re gone. You never get to hug them again, give them a simple ‘hello’, or tell them you love them.”