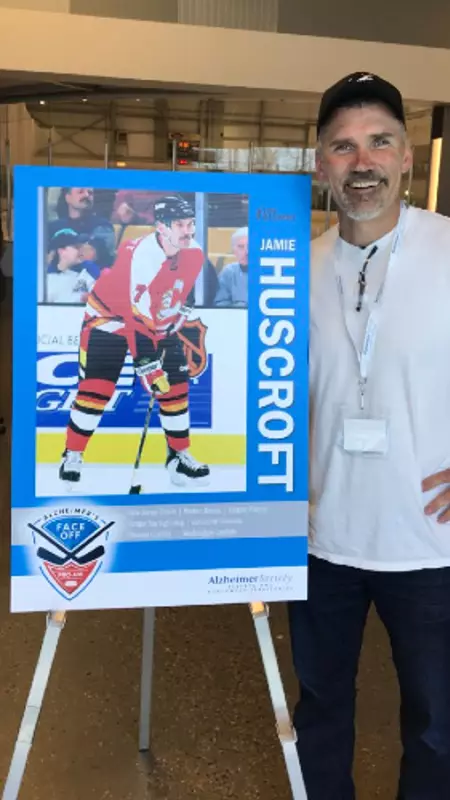

Posted: October 25, 2019

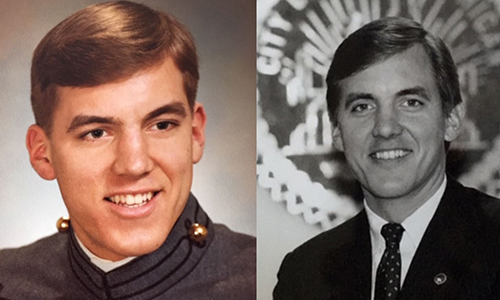

That included hiding every injury that he could for fear of losing his job. Huscroft estimates he suffered at least 14 concussions through his career. In 2001, after several concussions compounded to the point that he could no longer hide the symptoms, he had to walk away.

Huscroft now works as a director of facilities for a nonprofit hockey association in Washington. He’s surrounded by the game he loves and enjoys giving back to the hockey community. He is working hard to make sure the old culture of unnecessary hits and hiding hockey injuries is a thing of the past. To that end, Huscroft brought the Team Up Against Concussions education program to coaches and athletes at Sno-King Ice Sports as part of USA Hockey’s Team Up Against Concussions Week.

In the interview below, Huscroft talks about his love for the game, how concussions impacted his career, and the importance of sharing the Team Up Against Concussions message.

What was it like to have such a long hockey career and what has it meant to you since?

Playing professional hockey was never on the forefront of my mind growing up. I came from a small town in British Columbia and everybody played hockey. If there were 15 boys in the class, 14 of them played hockey. On weekends we all gathered around and watched Hockey Night in Canada. It was just something we did for fun. I never thought it would take me anywhere.

When I finally did start playing more seriously in junior hockey, I loved the culture, the players, the coaching. It really taught me hard work. If you had even an inclination or a thought of moving on to the next level, you had to work hard. That attitude continued on throughout my career. When I got drafted into the NHL the reality was that a mistake could cost you everything. Especially if you were someone with my talent. I didn’t have much talent. I worked hard and I was tough, but I lived on that fringe every day where I woke up every day not knowing how long I’d have a job.

That experience really helped me in the second phase of my life and career. It prepared me for all kinds of things. I work for a nonprofit hockey association and I have for the past 15 years. I’m surrounded by kids and people who want to be at the rink every day. It’s great. Every day I wake up and thank the good Lord that he gave me the chance to play in the best league in the world for quite some time.

What was your experience with injuries and concussions during your career?

Back in the day, most of us didn’t want to take a game off. I remember Kenny Daneyko who was the fiercest warrior I’ve ever played with or against in the NHL. There were times that his teeth got taken out, his finger was broken, or his foot got broken with a slapshot or something and I’d say to him, “Kenny – why don’t you take a couple games off and let me play?” I was the 7th defensemen and could have filled in. He said to me, “Husky, if I let you play, I may never get in the lineup again.” And I’d say, “Yea you will, you’re Kenny Daneyko!” But things like that made me feel like it didn’t matter what happened—you couldn’t sit out a game.

I wound up with at least 14 concussions. There were times that I’d take a big check and I’d get knocked out, but I’d be able to get right up. If anyone asked what happened, I’d tell them my knee went out or my shoulder was hurt but I would never let them know that I got knocked out. Unless it was blatantly obvious, because if I got known for having a glass-jaw or not being able to take a hit then by golly I wouldn’t have a job the next contract.

How did concussions lead to your retirement?

I was in Vancouver when I was probably close to 30-years-old. I played three exhibition games in a row and I got knocked out three times in a row over the course of a week. That was the beginning of the end for me. There is nothing you can do to hide the injury at that point. I think the hits were from a fight, an elbow, and a simple hit to the boards. It buckled my knees every time, but I got right up because that was my job. I knew that if I said I got a concussion, I could be out for months and I wouldn’t be sure if I was coming back to a contract or not. So out of pure stupidity I didn’t speak up.

I look back and I think “why did I do that?” But that was your life when you were in the thick of a career. That’s all you knew. You just said, “I’m a warrior. I’ll get around it and persevere.” Well, that didn’t happen, and my symptoms stuck with me. A year after that I took a simple body check in an AHL game and I never recovered. I was out of the game, and it kept me out.

I had deep, dark symptoms. The whole bit. But I was one of the ones who came out of it. I had a good support system. I rebounded and I luckily got a job in business where I was exercising my brain and working out physically on my own. I rebounded and I’m very fortunate.

How can Team Up Against Concussions help prepare teams to spot and respond to concussions?

No matter where you are and what you’re doing, if you’re playing sports concussions are a possibility. It all stems at the top with your team manager or coach. With Team Up, it’s vitally and critically important that we all get the coaches and managers and players to spread that message that teammates have a responsibility to look out for each other when it comes to concussions. It is so important that we recognize concussions on the ice or on the bench. To do that we get need to teach players the Team Up message in the locker room, on the team bus, and on the ice.

You can’t tough out a concussion. I think coaches all know about it, and I think USA hockey and Hockey Canada have done a lot to educate all these coaches throughout the Level 1-5 courses that athletes can’t tough out concussions. We know to respect concussions, and the challenge is to respond accordingly. The awareness is 100-fold now compared to when I was a kid.

Do you think the culture surrounding concussions has changed since you played?

In my day, in the 80s, we knew what concussions were, but we didn’t change our behavior much. Now that we all know and respect concussions, we know that you have to be really careful. Sports, especially hockey, has done a great job taking steps to protect our youth. There is no hitting until you get to the 13-year-old level. Even then the hitting is at the top tiers. Very few hockey players will ever go on to experience the full-contact game. Kudos to USA Hockey and the NHL for adapting, bringing this issue to the forefront, and protecting our youth.

Across the board leagues are taking unnecessary hitting out of the game. I oversee about 700 athletes in our adult league right now and I’m on the discipline committee. We do not accept hitting. If you take a run at somebody and hit them and knock them over, that’s it – you’re suspended. And if you do it a couple of times, we kick you right out of the league. And youth they’re doing the same thing. Kudos to all the people that are advancing this culture change.