Posted: January 5, 2017

Dave Behrman and football…how good was he?

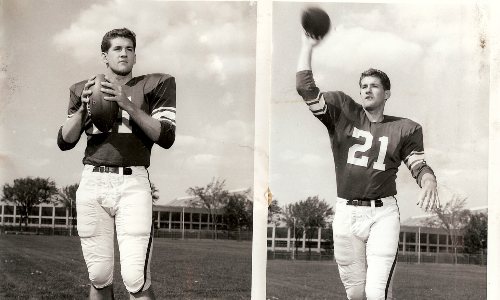

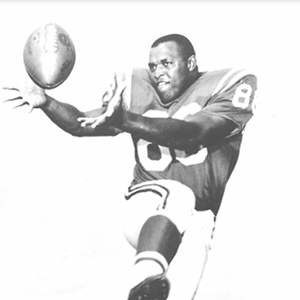

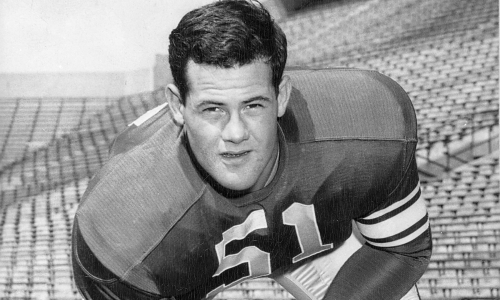

I was never an advocate of football and didn’t realize while growing up that he will forever be remembered as one of the greatest offensive tackles in Michigan State University football history. He was always big and as a 6-foot-4, 265-pound tackle he dominated opponents with his strength and quickness. MSU Head Coach, Duffy Daugherty, said that “If there is a college lineman anywhere with his speed, power, quickness, and intelligence, he has been well hidden.” Dave was an All-American pick in 1961 and 1962 and became part of the 1963 College All-Stars team that upset the NFL Champion Green Bay Packers, 20-17, on August 2, 1963 at Soldier Field in Chicago. After being distinguished as a first round draft pick in both the AFL and NFL, Dave’s AFL All-Star career with the Buffalo Bills and Denver Broncos ended in 1967 with back injuries. It was after that time period that he became a full time dad.

How do you remember your dad?

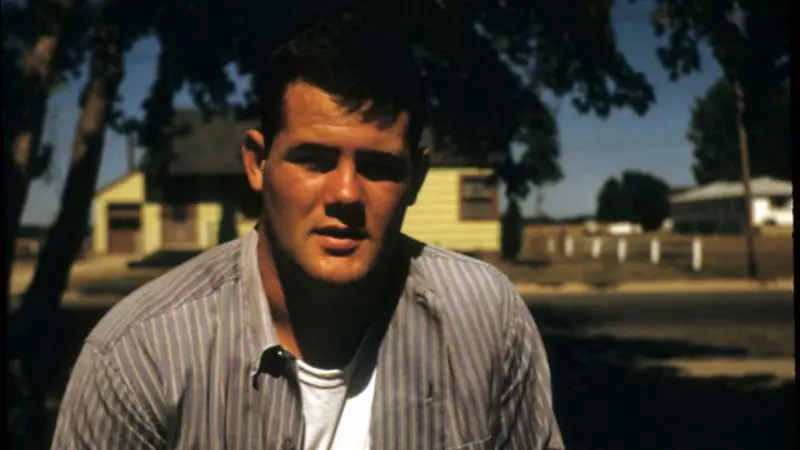

After football, he finished his business degree at Michigan State University and spent his career in the manufacturing and production environments in business and with the State of Michigan prison system tool and die shop. He loved tools and could make anything. He was a very intelligent man. At one point in my childhood my sister, Kellie, and I were wondering if he may have been one of those people who actually had a photographic memory, because he appeared to be able to retain everything he had ever read, learned or experienced. He also loved science and the value of scientific research, and I did too. He taught me that anything I ever needed to know could be found by researching it. At the same time, he taught me to pay attention to that pit in my gut, that feeling that you get when something isn’t quite right, and that the first thing that pops up might not be right, but it is the direction you go in seeking the answer.

Maybe that’s what caused him to be so good with “fixing” me. He worked with me before my ADHD diagnosis was available, without an owner’s manual, so to speak, by taking an interest in me, helping in what I was trying to do, helping to develop skills that I was good at. Since I learned by doing and not through lecture he would say, ‘don’t worry about mistakes, just make sure you learn something from them when you make them and try again.’ This is part of what motivates me today. His interest was always in what I was trying to accomplish. With my homework he simply read the chapter, looked at my assignment, and basically retaught me the lesson, one-on-one at the dining room table. Who knew just how effective that would actually be? This one-on-one fatherly touch continued when I was being punished for some teenage transgression. He would reconnect with me, alone, to discuss at length what happened, without judgement or anger, listening to me and even sharing his own personal experiences. All of those moments usually ended in some sort of agreement, often including a handshake, which I recognized as a contract that was in my best interest. And I honored every one.

Even as an adult today, one of my favorite early memories was a trip to grandma’s house and I realized that I had forgotten my baby blanket. We couldn’t go back because we had gone too far and I was not happy. My dad stopped at three stores along the way to grandma’s until we found a baby blue blanket with satin trim that made me happy. He was someone I knew I could count on.

All of this changed when the onset of his Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) began.

When did you notice that changes in him were taking place?

As he got older, his interest in his workshop at home helped him focus by being alone, just like the boating and fishing activities where he could retreat from the confusion of his mental decline and the conflict of a struggling marriage. As a natural introvert, with a talent in fixing and building things, he liked model boats and collected Karmann Ghias that he could repair and restore in his workshop. It was odd that he liked these tiny cars because he was so big and they were so small. Maybe the size of the cars represented the contradiction in his power and skill in football vs. his quiet, peaceful, and thoughtful demeanor as my dad.

Sadly, the depression, confusion, memory loss, lack of motivation, secretive behavior and balance issues, attributed to CTE, began to take over as he became more and more isolated. He lost the ability to maintain interest in friendships as well as being a devoted grandparent. We didn’t understand who he was becoming or what was happening. At times he was clear thinking in making a point and just as quickly he would lose all sense of logic and understanding of the truth. We reacted with anger, hurt and resentment and his behavior was hard on family relationships—because we didn’t know. As a result, we started professional medical support for him far too late. It wasn’t until we saw the Frontline Special, League of Denial: The NFL’s Concussion Crisis in October, 2013, that we began to understand what was happening to him, but the damage was done. When he died on December 9, 2014, he was diagnosed at the Boston University Medical Center for CTE with Stage III/IV CTE dementia.

How do you think about football as a result of your dad’s condition?

My dad never wanted my son, David, to play in the youth football programs in grade school. When he called me about the possibility of his playing, his advice was for David to pursue dog training or work related to animals. My dad didn’t eat, drink and sleep football like some athletes do—it wasn’t his passion. For me he was quiet, principled, shy and liked being by himself. It was sad to lose him to this disease (CTE). Knowing what I know now about my dad, I’m not so much in favor of football. I’ll admit that I don’t really understand the sport all that well and appreciate the fact that some people may disagree with my thinking.