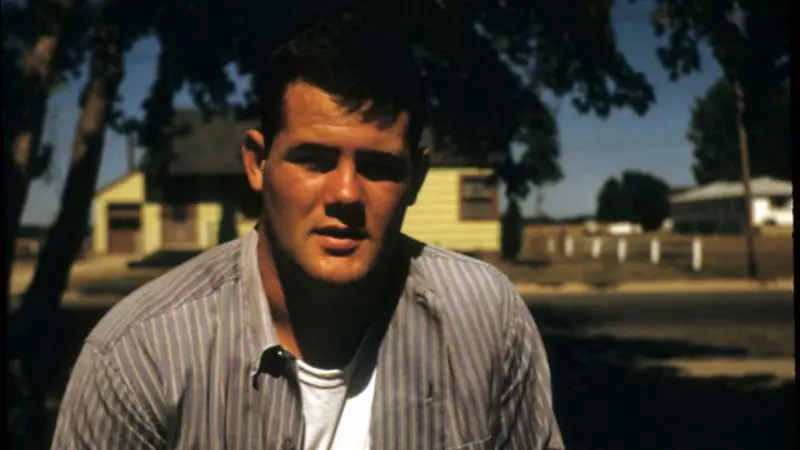

Curtis Baushke

Who was Curtis Baushke?

- God given soccer talents

- Love of fishing and the outdoors

- Gift of meaningful sports knowledge

When his troubles started?

- Multiple known concussions

- Ruptured disc in lower back

Curtis had researched concussions and chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), and was certain that he had CTE. Five years before his death, Curtis wrote a college paper about concussions.

“CONCUSSIONS – It is not just the pros that have problems!”

By Curtis Baushke – 2009

Concussions range in significance from minor to major, but all share one common factor…they temporarily interfere with the way your brain works. They can affect memory, judgment, reflexes, speech, balance and coordination. Most concussions are caused by some kind of blow to the head. Concussions don’t always result in loss of conscientiousness. Oddly enough, most people don’t even black out but this was not the case for me.

I’ve been playing soccer since I was five years old and in my 14 years of playing I have had two major concussions and two mild concussions, all of which I blacked out for more than 10 seconds. My most severe concussion was when I was fourteen and playing in a regional soccer tournament in the Atlanta, Georgia area. I was playing fullback and defending our goal, when I went up in the air to win the ball from an opponent. WHAM, the guy in front of me went up at the same time but instead of bumping heads, he put an elbow right smack into my nose. I completely blacked out for what I thought was 20 to 30 seconds. When I finally woke up, I was looking up at the faces of our trainers. I could see my reflection in one of the trainer’s sunglasses. My nose was broken and resembled something like a “Z” shape and my white jersey was covered in blood.

I thought it couldn’t get any worse than that experience but another bad concussion would find me in my sophomore year of high school. For our psychical education class we were required to complete a six week bowling program. When we arrived at the bowling alley, I went to my normal lane and started using one of the house’s bowling balls. Than another kid in our class came up behind me as I was lining up in the lane and told me to give him that ball. I ignored him because they were all house balls and everyone had an equal right to use any ball at the alley. The next thing I know the kid had picked up another ball and swung it at the side of my head. I collapsed on the lane and blacked out for a few seconds. When I regained conciseness, there was a burning feeling in my knees and I collapsed again onto the floor. The doctors told my mother that I had suffered a mild to serious concussion. Concussions are not just a sports related problem; violence in society is also a source.

During my years of playing soccer and other contact sports I have “knocked heads” with other players, elbows, and soccer goals many times. Winning the soccer ball out of the air at mid-field or scoring soccer goals with my head on corner kicks was my specialty on my teams. My last and most recent concussion happened during my senior year soccer season. Once again I was defending our goal and went up for a header. This time a fellow teammate went up at the same time and the back of his head made contact with my forehead. I suffered another concussion, more blood and eight stitches above my eyebrow. The team doctor stitched me up on the sidelines, than I went back into the game because I was needed.

Since I have had many concussions, I started to read up on the research being done for pro athletes who have retired after suffering multiple concussions. Some of the effects have been long term…I am nineteen years old and have suffered four known concussions (when I blacked out), so this matter effects me. I would like to know if there is anything that is going to help me with my side effects. From my head traumas, my side effects have consisted of horrendous migraine headaches and terrible mood swings. With the most intense migraines it affects my eye sight and balance when I try to stand up. They hurt so badly that it makes it hard for me to speak or even stand. Starting my junior-senior year in high school during the day, I usually would have to take some strong medicine, lie down in a dark room and fall asleep hoping it would be gone when I wake up.

More research should be initiated for the study of concussions. It is not just pro athletes who suffer with problems. It should start with middle school sports all the way through high school and college. Allowing kids to play too soon after a concussion is very dangerous. We need to find out the actual damage concussions cause to athletes and ways to protect them. We should pay more attention to this problem.

There needs to be more research done to figure out what we can do! I feel this way now…what will it be like when I am older?

An Athlete Felled by Concussions, Despite Playing a ‘Safer’ Sport By Dan Barry, New York Times, June 21, 2015. A version of this article appeared in print on June 22, 2015, on page D1 of the New York Times.

Words written and posted on Facebook by Curtis’ brother Ryan William Baushke the day after Curtis’ death:

I am at a loss for words…last night my brother Curtis suddenly passed away in his sleep. I am devastated being that I lost my best friend, hunting partner and fishing buddy. There are always ups and downs in any relationship but no matter what I always could count on him and he would have my back. Curtis, I know you know this but I love you more than words can describe. You’re a man of integrity and courage that would give your shirt off your back for anyone. I will miss you every day, until I see you again in heaven. I know you’re in a better place and hanging out with the good Lord himself. May you rest in peace and the good Lord blesses your soul. I will never forget all the good times…see you next duck season in the blind. Love you always, your bro.

Terry Beasley

Dave Behrman

Dave Behrman and football…how good was he?

I was never an advocate of football and didn’t realize while growing up that he will forever be remembered as one of the greatest offensive tackles in Michigan State University football history. He was always big and as a 6-foot-4, 265-pound tackle he dominated opponents with his strength and quickness. MSU Head Coach, Duffy Daugherty, said that “If there is a college lineman anywhere with his speed, power, quickness, and intelligence, he has been well hidden.” Dave was an All-American pick in 1961 and 1962 and became part of the 1963 College All-Stars team that upset the NFL Champion Green Bay Packers, 20-17, on August 2, 1963 at Soldier Field in Chicago. After being distinguished as a first round draft pick in both the AFL and NFL, Dave’s AFL All-Star career with the Buffalo Bills and Denver Broncos ended in 1967 with back injuries. It was after that time period that he became a full time dad.

How do you remember your dad?

After football, he finished his business degree at Michigan State University and spent his career in the manufacturing and production environments in business and with the State of Michigan prison system tool and die shop. He loved tools and could make anything. He was a very intelligent man. At one point in my childhood my sister, Kellie, and I were wondering if he may have been one of those people who actually had a photographic memory, because he appeared to be able to retain everything he had ever read, learned or experienced. He also loved science and the value of scientific research, and I did too. He taught me that anything I ever needed to know could be found by researching it. At the same time, he taught me to pay attention to that pit in my gut, that feeling that you get when something isn’t quite right, and that the first thing that pops up might not be right, but it is the direction you go in seeking the answer.

Maybe that’s what caused him to be so good with “fixing” me. He worked with me before my ADHD diagnosis was available, without an owner’s manual, so to speak, by taking an interest in me, helping in what I was trying to do, helping to develop skills that I was good at. Since I learned by doing and not through lecture he would say, ‘don’t worry about mistakes, just make sure you learn something from them when you make them and try again.’ This is part of what motivates me today. His interest was always in what I was trying to accomplish. With my homework he simply read the chapter, looked at my assignment, and basically retaught me the lesson, one-on-one at the dining room table. Who knew just how effective that would actually be? This one-on-one fatherly touch continued when I was being punished for some teenage transgression. He would reconnect with me, alone, to discuss at length what happened, without judgement or anger, listening to me and even sharing his own personal experiences. All of those moments usually ended in some sort of agreement, often including a handshake, which I recognized as a contract that was in my best interest. And I honored every one.

Even as an adult today, one of my favorite early memories was a trip to grandma’s house and I realized that I had forgotten my baby blanket. We couldn’t go back because we had gone too far and I was not happy. My dad stopped at three stores along the way to grandma’s until we found a baby blue blanket with satin trim that made me happy. He was someone I knew I could count on.

All of this changed when the onset of his Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) began.

When did you notice that changes in him were taking place?

As he got older, his interest in his workshop at home helped him focus by being alone, just like the boating and fishing activities where he could retreat from the confusion of his mental decline and the conflict of a struggling marriage. As a natural introvert, with a talent in fixing and building things, he liked model boats and collected Karmann Ghias that he could repair and restore in his workshop. It was odd that he liked these tiny cars because he was so big and they were so small. Maybe the size of the cars represented the contradiction in his power and skill in football vs. his quiet, peaceful, and thoughtful demeanor as my dad.

Sadly, the depression, confusion, memory loss, lack of motivation, secretive behavior and balance issues, attributed to CTE, began to take over as he became more and more isolated. He lost the ability to maintain interest in friendships as well as being a devoted grandparent. We didn’t understand who he was becoming or what was happening. At times he was clear thinking in making a point and just as quickly he would lose all sense of logic and understanding of the truth. We reacted with anger, hurt and resentment and his behavior was hard on family relationships—because we didn’t know. As a result, we started professional medical support for him far too late. It wasn’t until we saw the Frontline Special, League of Denial: The NFL’s Concussion Crisis in October, 2013, that we began to understand what was happening to him, but the damage was done. When he died on December 9, 2014, he was diagnosed at the Boston University Medical Center for CTE with Stage III/IV CTE dementia.

How do you think about football as a result of your dad’s condition?

My dad never wanted my son, David, to play in the youth football programs in grade school. When he called me about the possibility of his playing, his advice was for David to pursue dog training or work related to animals. My dad didn’t eat, drink and sleep football like some athletes do—it wasn’t his passion. For me he was quiet, principled, shy and liked being by himself. It was sad to lose him to this disease (CTE). Knowing what I know now about my dad, I’m not so much in favor of football. I’ll admit that I don’t really understand the sport all that well and appreciate the fact that some people may disagree with my thinking.

© 2016, James Proebstle

John Bell

The College Years

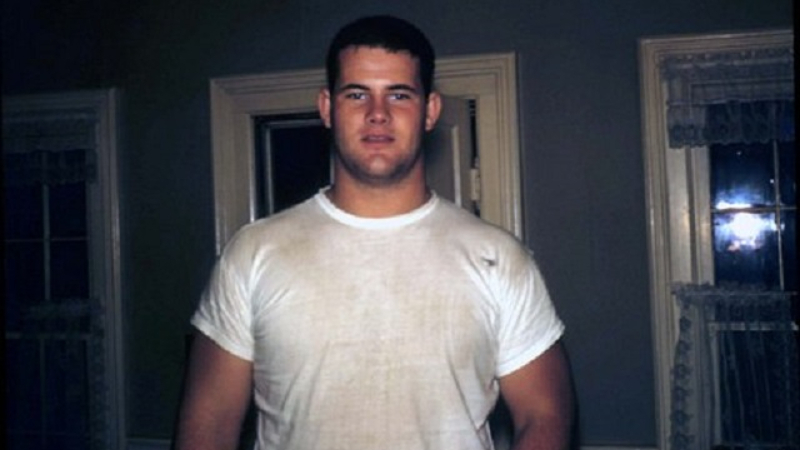

Since 1950, Nebraska Football has honored one of its players each year with the Tom Novak Award for a player that “best exemplifies courage and determination beyond all odds in the manner of Nebraska All-American center, Tom “Train Wreck” Novak.” John Bell earned the Tom Novak award in 1973 for playing the game with intensity—reckless abandon as the coaches called it. Fighting through injuries and personal setbacks, John, #66, was tough and a critical part of Nebraska’s 1971 National Championship team, 1972 Orange Bowl championship team, and 1973 Cotton Bowl championship team. This was in addition to his mention on the All-Conference and All-American academic award roster and to John being a two-year letter winner on the Husker wrestling team. Middle guards don’t often get that level of notoriety. John was blessed with exceptional quickness and power as he leveraged his 202-pound body among interior linemen of a much larger stature.

Raising a Family and Building a Career

John was known to have a strong work ethic, working through his teen and college years. He obtained a teaching credential from Nebraska. Wanting to work with adolescents, he started as a youth counselor with the California Youth Authority detention system. Family priorities changed and a move closer to family took John to high school teaching and administration for the majority of his career. He loved working with kids and connected with them at all levels through a knack for good ideas and resourceful programs. His spontaneous nature for making things happen enriched many young peoples’ lives.

As children (Jared-son and Carrie-daughter), growing up with their father was always an adventure. He was always trying to introduce his children to new things and broaden their horizons. He challenged them every chance he got. He was at every game, every debate, every play, dance or choral recital, and every parent-teacher meeting. He was honest with his children and treated them with respect and listened whenever they had complaints and problems. Their communication was open and safe whether it be about sex, drugs or world events. John and his then-wife Paula divorced, and John insisted on joint and equal custody for his children in court.

He continued to include his children in his life even when he started dating his eventual second wife, Kathy. He always checked in with Jared and Carrie to make sure that they liked her. He even included the two kids on dates. John married Kathy in 1988 and they remained together until his death. Carrie and Jared were in the wedding and were also included on a family hiking trip/honeymoon—a “family-moon” long before it became trendy.

Carrie (Car-bear) and Jared (Jar-bear), as he called them, would attest to John’s level of enthusiasm via the many outdoor adventures and family trips as John’s reputation as papa-bear became legend. Until about 2007, Jared and Carrie would describe their dad was a bright shiny person. His Memorial Day parties were legendary. Their family and friends would gather. Everyone ate like kings, listened to music turned way up, and swam for hours. The kids were always going on road trips and encouraged to explore and try new things. He was firm and pushed the kids to their limits but was always kind and full of love and instruction. Carrie’s desire to see the world and live life fully were seeds planted by her dad. He also taught her how to be loyal and brave, to fight for the weak, and stand up to bullies. John was very proud of his kids.

As time went on, however, his lack of mobility and constant pain from arthritis restricted his need/desire to work out and remain physically active. The loss of this physicality in sports, which was so validating to John and so much a part of his youth, created issues. In his younger years, it was the physical contact inside and outside of wrestling and football that kept him focused.

John died on March 31, 2016, from a very aggressive onset of polyneuropathy, septic shock, coupled with complicating infections. The prognosis for recovery was not positive and after a week in ICU he was put on life support. Sadly, after two days of continued decline the family had to make the decision to take him off life support. Upon hearing of John’s passing many said that their lives would not be what they were today without John Bell. The family had just a small ceremony, but they received many cards, and Facebook posts in addition to the newspaper notice acknowledging John’s contributions.

Battling the Demons

John’s life was not easy, as his bi-polar II and ADHD diagnoses tormented him throughout adulthood. He just didn’t feel normal. Anger, irritability, binge drinking, hurtful comments, fault-finding, blaming, and rages triggered isolation. He often got very upset with friends and family and became disappointed with who they were. This led to negative comments as he would “just let them have it.” It was hard to recognize at times, and his kids internalized that this behavior was “not their father” and that he was not a “horrible person.” But it was painful to watch and also painful to be the brunt of the side effects. In an attempt to mask his demons, John’s risk-oriented personality lead him to more alcohol and recreational drugs. It was possible that the alcohol and drugs were a subliminal strategy to mask or suppress the undefined underlying medical issues. It was not a solution that worked and likely led to a psychotic break in his late 40s. Medication was prescribed but not always used.

His body wore down from the years of battle. With the loss of a physical outlet he turned to writing poetry and engaging in the arts more and more. But, as time passed the poetry became darker and darker and his trips to “outer space” went from once every six months to every couple of months. He would call his family several times a day at all hours of the day. He was always upset about things from the past, things that were unfinished or unresolved. Jared would sit and talk with him as much as he could. Sometimes John’s anger was directed at Jared for something he did or for not being there to answer his phone call. Most of the time he praised Jared for things he accomplished twenty years earlier or for the great father he was. He would end every call with, “love is love” and Jared responded with “not fade away.”

From their perspective, not being able to do as much physically made their dad grumpy and sad as he started cycling between being up and manic and down and depressed. He always had a fiery temper but it was easily provoked as he got older and deteriorated to where the littlest things would set him off. Maybe someone said the wrong thing or you slept in too late while visiting or weren’t ready to walk out the door the moment he was. Or, he would call within minutes of the last call and his messages would usually start nice and normal and then would get angrier. In the last few years he had left some pretty accusatory messages and would often call them names or swear at them. He started to act paranoid about how we were not being loyal enough or grateful enough.

John was not great at taking his bipolar medication because he didn’t like being “flattened out.” It wasn’t him, but then again neither was the person he was becoming. At a certain point we always wondered what dad we were going to get when the phone rang or when we went to visit. These rages within the family would lead Kathy to warn the kids that John was in “crazy land right now” and not to try to deal with him. Often, the events involved a very specific timeline that wasn’t honored and John would become unhinged. It was as if the unresolved details themselves would upset him. At times, John’s desire for closure would trigger an almost “stalking” response to get things settled. The many layers to the issues he was dealing with made productive employment unrealistic.

Kathy, John’s constant companion and soulmate, sought support in counseling, visits to AA and Kaiser with John, visits to Al Anon on her own and the loving support of friends and family to cope with the many challenges. Naturally, social contact with others disappeared with John’s difficult interpersonal issues.

Carrie and Jared struggled to reconcile the idea that they had grown up so loved and supported and with so much magic and fun only to see the last 20 years end with what seemed like a totally different person as a father. The family saw John’s great big smile less and less, heard that jolly uncontrollable laugh less and less.

In the last two years of his life John spent more time lost in his head than with the rest of his family. He and Kathy would come visit for a day to watch the grandkids play sports. But after a few hours, he would get antsy and was ready to go. He never seemed 100 percent at ease with his surroundings. It was like the man they grew up with was trapped inside. The changes happened slowly at first, but as time passed, the decline of the man his children had called dad sped up with every year. They would all agree that one day he was his normal self and then suddenly it seemed like a switch had been flipped and he had a different personality. With sadness, anger, and confusion as a forefront to his emotions—complications set in with continued self-medication with alcohol. His love for his family was never a question. It was always there, but sometimes residing too far down to be seen.

Donating John’s Brain

After seeing the movie, Concussion, it was Carrie that made the connection with John’s behavior issues and CTE. When we realized he wasn’t going to make it, Kathy contacted Boston University’s Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) Center, as well as Lisa McHale at the Concussion Legacy Foundation (CLF) to find out if they would take John’s brain after he died. Both Boston University and CLF were enormously helpful in their efforts and in time John was diagnosed with Stage III-IV CTE. With this diagnosis, the family achieved a sense of peace and forgiveness in having to take John off life support. There was a sense of reconciliation with the two dads whom they had come to experience. Part of what made it so hard for his family was that John had always been a pillar of strength and athleticism. He was rarely sick and he recovered quickly. He was always active, athletic and strong—in the end he was none of those things.

How has your attitude toward football changed?

Kathy remains steadfast in her support for football. She feels strongly that football provides an outlet or release for the aggression needs of many young men. The physical nature of the game, while not for everyone, is perfect for some. While her concussion awareness is much better today, she hangs onto the hope that the equipment will continue to become better and that testing of athletes will help improve the player safety aspect of the game. She is optimistic that we can become smarter and that the game will evolve.

Jared’s wife now worries about him with the eight concussions he experienced over his playing time.

Carrie feels that John’s story is important for people to read so they can understand that CTE can happen, even if the athlete did not play professional football in the NFL.

Love is Love…

Not Fade Away

Copyright © 2017, James Proebstle

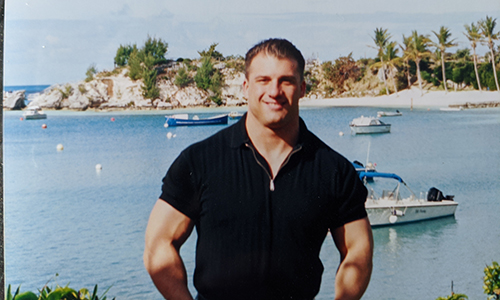

Wes Bender

Wes Bender had a kind heart. He would take the time to speak with anyone and share his experiences and challenges.

Wes started playing Pop Warner at the age of six and was passionate about football. The very first time he took a handoff, he ran 80 yards for a touchdown. Wes was smaller than the average kid, but overcame that challenge with his speed.

Wes was bright but sometimes his words and numbers were scrambled. His teachers, coaches, friends and family helped him until a key teacher recognized he had dyslexia. At the time, learning disorders like dyslexia weren’t common knowledge. Still, Wes overcame this challenge thanks to programs to help dyslexic students.

By the time high school rolled around Wes began to emerge with uncommon size, speed, strength, smarts, and competitiveness. The results? A powerful offensive running back who started as a freshman and sophomore at Burbank High School in southern California. But at the start of his junior year, the coaching staff wanted to move Wes to the offensive line. The proposed switch challenged his dream of being a college running back so he transferred schools to the cross-town rival, John Burroughs High.

Wes’ transfer to John Burroughs produced one of the most productive high school offenses in Southern California history. Against his old team, Wes scored a 50-yard touchdown run in a 41-0 victory. Wes’ success led to his induction into the John Burroughs Hall of Fame in 2015.

Dyslexia made it difficult for Wes to learn a foreign language, a college requirement. Many colleges were interested and offered scholarships, so he attended Glendale Junior College to refine his skills. Wes went on to set several Glendale College records and lead his team to win the Western State Conference title. His time at Glendale earned him a full athletic scholarship to play for the only college he would consider, the University of Southern California.

Wes started for two years at USC and set several weightlifting strength records that still stand posted in the weight room today. Wes was a powerful, hard-hitting fullback, routinely stuffing linebackers at full speed, blocking players in the open field, knocking them to the ground, and creating holes for the tailbacks to follow.

Mazio Royster was the tailback who benefitted from Wes’ blocks at USC.

“Wes was a great teammate, but an even better person,” Royster said. “It was my job as the tailback to read the fullback’s block. These were some of the most violent collisions imaginable and Wes never shied away from contact, complained, or even asked for praise.”

Wes’ incredible blocking earned him a shot in the NFL. Marty Schottenheimer, then head coach of the Kansas City Chiefs, said Wes was one of the best blocking running backs he had ever seen come out college.

Wes accomplished his dream to play in the NFL with the Chiefs. Wes earned the nickname “Fender Bender,” delivering crushing hits, knocking out All-Pros and Hall of Famers while team members would joke and tell him to tone it down a bit. An ankle injury sidelined him that year, leading him to his hometown Los Angeles Raiders. Wes was referred to as “Bam Bam” with the Raiders, receiving game balls and Monday night honors until he moved to the New Orleans Saints two years later.

New Orleans was Wes’ final stop in the NFL. He played for the “Coach” Mike Ditka. Coach Ditka preached tough, hard-hitting football. Wes was at home in New Orleans, winning more game balls, and creating key plays with his blocking.

Wes’ position and style of play led to countless head impacts. He suffered a reported 23 concussions in his football career. He retired from the NFL in 1997.

The football chapter of Wes’ life was closed, opening the door to the business world. Wes always loved to modify cars and trucks, so he started a successful business building modified four-wheel drives and other auto specialties. Wes was very good with people, had a kind heart and would chat with anyone. One of his clients thought he might enjoy the sales and service elements of the concrete business.

Wes was very successful running large concrete jobs in Los Angeles, but some things in his life were not clicking fully. Sleep became more challenging, as Wes would wake up frequently at night. He became overwhelmingly stressed by simple things most people can cope with easily. The concrete business was very competitive, stressful, and becoming too much for Wes, so he decided to retire from that business due to health concerns.

The final chapter was starting a business with family in the medical and dental industry. This was perfect, helping the business get started at his Alma Mater USC and crosstown rival UCLA. The UCLA dental program loved Wes, despite him being a USC alum.

Wes could always make you laugh and could remember movie lines from 30 years ago or jokes from childhood. But he strangely couldn’t remember what he had for dinner the night before, or a conversation he had with a salesperson a week ago about training.

“What was going on?” we’d ask Wes.

Wes would get frustrated and say, “I just can’t remember.”

Simple tasks, things most people don’t think about became a challenge. Wes would run to the store to get milk and then forget why he went to the store.

My brother Wes passed away in his sleep on March 5, 2018 at age 47. The stress of his life was too much for his heart and his brain.

Four months before his death, Wes completed his will and stated his intention for his brain to be studied at the UNITE Brain Bank in Boston. At the time, we thought this was an interesting decision, but we followed his request and sent his brain to the Brain Bank.

There, researchers diagnosed Wes with Stage 2 (of 4) Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE). We didn’t know it at the time, but Wes’ intuition about his brain was correct.

Matthew Benedict

Matthew Benedict’s One Last Goal

Looking back on Matthew’s life we often wonder: what went wrong? We believe the brain injuries he sustained in his youth played a significant role. His first concussion came at a very young age. It was a collision with a baseball and his eye socket. There were other hits to the head we did not know of – childhood games in the back yard, collisions in football, hockey, and lacrosse. Matthew never wanted to be a burden. Matthew was three years old when he started playing organized hockey. He started soccer soon after, then lacrosse and football all by the age of 12. Matthew was a fierce competitor who would sacrifice himself for a win.

He was rarely sick, and when he was, he would will himself better. We can count on one hand the number of times he went to the doctor because of illness. He was healthy physically and mentally until late in 2013, when he sustained a couple of hits to the head in a game while playing defensive back for the Division III Middlebury College football team. True to form, he tried to “will” himself better and hid his PCS out of embarrassment. Plus, he didn’t want anyone to worry about him. We never even knew he started experiencing symptoms of PCS after those hits until he fessed up two months later when he was home for winter break, and he couldn’t hide it from us any longer.

Matthew never complained, but in January of 2014, when we took him to the doctor for his lingering concussion symptoms, he revealed that from a very early age he had his “bell rung” more times than he can remember. He never considered his “bell rung” incidents as sub-concussive hits or concussions, and he never told us about them until it was too late, and the damage had already been done.

In May of 2015, one-and-a-half years after he suffered those debilitating hits, and the day after he graduated from Middlebury College, Matthew wrote a piece called “Start the Conversation Now…Life is Precious.” This was the first time we realized how badly Matthew was hurting. Before then, we were concerned, but not alarmed. This piece rocked our world and deep down we knew Matthew may be in serious trouble. Here are some of his words from that piece:

“Before I begin, I do not want to hear any words of how courageous I am because frankly it is the opposite. It is much easier now that I graduated to tell my story, so I apologize for not having more courage…I do not like to draw attention to myself and often get embarrassed in front of crowds or when other people talk about me. I have suffered two severe episodes of depression these past two years. These times have been the scariest times of my life and have lasted many months. Not scary because I was actually scared, but scary because I felt nothing at all. The emptiness was devastating and it was beyond frustrating not knowing what really caused it.

The first episode was right after the football season of 2013… the season ended and I was honored 2nd team all-NESCAC and then was voted team captain by my peers and teammates at our awards banquet a few weeks after the season ended. This was one of the worst things for me that made my depression even worse. My self-confidence and self-worth tanked so much that I figured I was not worthy of any award or leadership position and any thoughts of the future made it worse. How was I supposed to be a captain when I didn’t even have confidence in myself? Or what would my teammates think when they found out about it? I wanted to hide from everyone and everything. I could not carry on a conversation of any depth and most conversations were people congratulating me. Congratulating me on what? Not being able to get out of bed? For taking hours and hours to work in the library only writing a paragraph? I had no reason to be congratulated. I wasn’t working out and I was setting a terrible example for my team. I stopped calling home, going out with friends, or having any joy in life. I withdrew from everyone and everything and could not even look the wonderful beautiful girl in the face to say I could not carry on our relationship after a few months leaving her heartbroken and confused. Every time I hid I later on regretted it more and more which made me feel even worse. Self-harming thoughts began to creep in… I felt like everywhere I went people knew right away about me and were judging me ruthlessly. I refused to tell my friends and family the extent I was feeling because I was embarrassed. I was ashamed of myself… I was such a coward. I was a terrible person. My teammates thought I was this great guy and to be honest I was not being that at all. I thought I was going to flunk out and my future was over. I thought I had made it all this way only to fail the first semester of my senior year. I thought I would let my school, team, friends, and ultimately family down. Some captain I was…”

After Matthew wrote those words and published them online, he felt the stigma in revealing his weaknesses to the world. He later wrote: “it is the most frustrating thing to feel ostracized from others or feeling like they look down on you because you have been suicidal in the past. It is bad enough the guilt we carry around for considering suicide that we do not need to feel judged by others.”

Matthew often commented that after he went public with his mental health struggles, people looked at him and treated him differently. He tried to go on with his life, reluctantly agreeing to meet with different doctors, but he avoided them as much as possible because he didn’t feel there were any answers to his problems. He believed most people didn’t understand him. It’s not like he had a broken leg that could easily be diagnosed and fixed… he had a broken brain. We were in constant search for a proper diagnosis, treatment or a cure for Matthew, but we simply couldn’t find the answers he so desperately needed.

Matthew continued his life as best as he could. Enrolling in law school, earning an excellent GPA some semesters and having to medically withdraw from other semesters because of anxiety, depression, and feeling like he was the dumbest student in school. In January 2019, about five years after his initial diagnosis of Post-Concussion Syndrome, he wrote thoughts about ending his life, but like the other times, he did not share his thoughts with anyone. After he passed, we found these notes he wrote about six months before his death:

“The first time I thought about suicide was my junior year of college. My football team had won a share of the league championship. I was voted team captain. I was seeing my dream girl and she was a golden girl herself. I fell in love for the first time. I was killing it, no pun intended.

Despite all the success, I fell into a deep depression for the first time in my life. All of a sudden, my whole livelihood was ripped from my eyes. I had no idea how it happened. Towards the end of the football season I had the game of my life versus Trinity College our nemesis. In the 4th quarter the quarterback, who was a 200 pound 5’ 10” raw athlete, ran me over full speed. I do not remember getting up from the hit. But the coaches would have had to drag me off the field to remove me from the game. I kept silent and hid from it. It was for the Championship. I made 19 tackles and was named player of the week for my league. I knew I was concussed but I was too proud to admit it. The adrenaline was through the roof. All I had trained for and worked so hard for was on the line during that game. I was chasing the glory of being a Champion. We did it. We won the flashy rings. A game I will never ever forget. Besides the quick bit after that hit. After the game, I went out and got drunk to celebrate. My teammates knew my head was bothering me but I told them I was fine. I wasn’t.

Three weeks later I went home to see my family for Thanksgiving. They had no idea how bad things were. I played it off like I was still the golden boy. I had learned how to put on a good show for the outside world. When I returned I slept for most of the day. Stopped going to class. Lied to my friends about going out while I was by myself. Stopped responding to my friends. Ran away from the girl of my dreams. I felt worthless… My whole life was a lie. I was no Golden Boy. I was a coward. I was weak. That is what I told myself…I went on a drive one night to try to clear my mind…It was a life altering experience.”

Six months after Matthew wrote this, nearly six years after he was diagnosed with PCS, Matthew died by suicide. His PCS robbed him of his ability to see the value in his life and how much others loved and respected him. It robbed him of his ability to think clearly and love deeply. On the day Matthew died, we believe his soul had already been stolen from him.

According to the National Institute of Mental Health suicide is a complex public health concern, and there is no single cause. Suicide most often occurs when stressors and health issues converge to create an experience of hopelessness and despair.

At the time of Matthew’s death, he was a summer associate for a law firm. He cherished his inalienable rights of liberty and freedom. In life, he relentlessly tried to search for the truth. Unfortunately, we remain without answers about his death. We do know, though, when Matthew attempted to be transparent about his mental health, he felt judged. This led him to avoiding opening up to loved ones and discontinuing appropriate treatment. Even though he realized this was a problem, he was reluctant to properly address it because the stigma was so powerful. We feel Matthew would have wanted us to resume his battle by helping others realize that mental health is just as important as physical health, and “it’s OK not to be OK.” He would have hoped others could live and be free from the shame associated with mental illness. We believe he would have encouraged us to spread the message so others would not feel the guilt he felt. We know he would have wanted all of us to be kind and not abandon each other during our times of need. In one of the pieces Matthew wrote and published, he had some advice for all of us:

“…Start the conversation. No more hiding. No more silence. Speak up. Reach out. Tell people you love them. Make the community and the world a better place. Mental health is no fun but it is necessary to talk about. Don’t be like me. Don’t wait. Be brave…You see what others have and often compare yourself… I still regret my actions and will never fully be able to forgive myself but I challenge you to not be like me… If we want to make the world a better place we must act. We cannot be silent…Tell everyone you love them every single day and treat those you don’t know with the same love… start the conversation now… life is precious…keep the conversation going…and listen…don’t just hear, but listen to those you love and listen to everyone around you…make sure they know they matter.”

Suicide is preventable and help is available. If you are concerned that someone in your life may be suicidal, the five #BeThe1To steps are simple actions anyone can take to help someone in crisis. If you are struggling to cope and would like some emotional support, call the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988 to connect with a trained counselor. It’s free, confidential, and available to everyone in the United States. You do not have to be suicidal to call. If you’re not comfortable talking on the phone, consider using the Lifeline Crisis Chat.

If you or someone you know is struggling with lingering concussion symptoms, ask for help through the CLF HelpLine. We provide personalized help to those struggling with the outcomes of brain injury. Submit your request today and a dedicated member of the Concussion Legacy Foundation team will be happy to assist you.