Reggie Fleming

Hunter Foraker

As the coroner walked through Hunter Foraker’s apartment in Dallas, Texas, on September 18, 2017, she noticed football helmets displayed on his shelf.

They called Kim Foraker, Hunter’s mother, and asked her if she was interested in having an autopsy on Hunter’s brain. In their search for answers following Hunter’s suicide, the Forakers agreed.

Four days earlier, Kim, her husband Bill, and their daughter Jordan all spoke with a jovial Hunter. He was getting a carwash. The new job was great.

“Looking back on it, we all think he was drinking and just a little happier than usual,” Jordan said.

“Perfect”

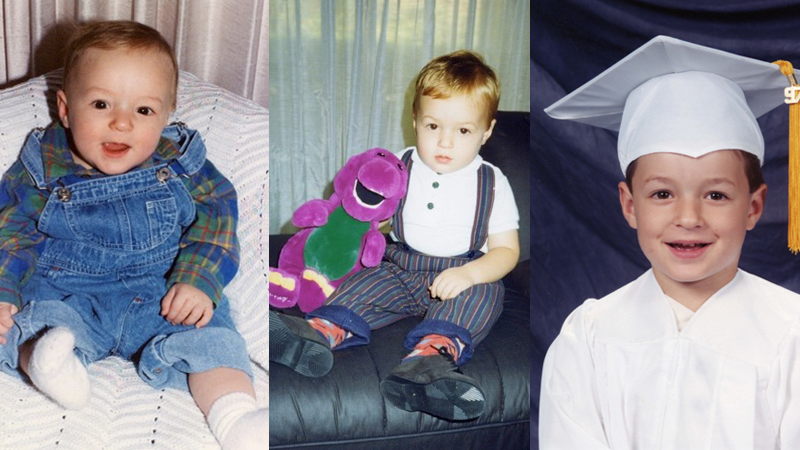

Hunter Foraker was born on May 11, 1992. Within a year, he was in skis and joining his dad Bill on the mountains of Colorado. His childhood was spent doing all kinds of outdoor activities like mountain biking, camping, hiking and fishing.

Normal kids may fib every so often. Young Hunter was steadfastly loyal and honest to his family.

He had a drive for perfection that carried over to the classroom and every field Hunter stepped onto.

Hunter was a teacher’s dream. He may not have been the very sharpest in his class, but he was quiet, humble, respectful, attentive, and determined to do his best. His competitive spirit pushed him to do more and do better than his peers.

“I always thought it was the pressure to be perfect,” Jordan said. “He would stay up studying and working for hours because things didn’t come as easy to him, but he would put in the time to understand it just the same.”

Hunter dabbled in many sports but found the most success in football. With Bill as his coach, Hunter started playing tackle football in second grade. His size, athleticism, and aggressiveness made him a natural fit at linebacker.

“It was so wonderful to see Hunter and Bill together in a sport that gave Bill so much pleasure and fulfillment as a youth and knowing that Bill was coaching Hunter in the correct methods of hitting and tackling so that Hunter would not be injured,” Kim said.

“I Remember Seeing ‘Big Green’ Everywhere”

It didn’t take long for Hunter to make a name for himself on the Mullen High School football team in Sheridan, Colorado. He made varsity his sophomore year and was named a captain the following two years.

Hunter’s senior season at Mullen in 2009 included a long list of accomplishments. He recorded 100 tackles and led a Mullen defense that allowed just 5.7 points a game in their 14-0, state championship season. Hunter was named to the 5A First Team All-State roster and the state’s All-Academic team.

“I remember his senior year we went to some fancy dinner as a family, little did I know it was because Hunter was nominated for a pretty big award,” Jordan said. “Hunter acted like it was just another banquet. He was so humble.”

Football was a means to an end for Hunter. He decided before his junior year of high school that he wanted to attend an Ivy League school. He worked diligently and had great grades but knew he would struggle to get into his dream schools without football.

“He wanted to play with a higher level of player,” Kim said. “A player that wasn’t simply focused totally on football but had a future outside of football in mind.”

Dartmouth became the apple of Hunter’s eye. He loved that skiing was encouraged after the football season. He would be right at home in the cold Hanover, New Hampshire winters. He returned from his visit to campus and wrote “BIG GREEN” on everything he could at home. Later that year, he was ecstatic to learn he was accepted into Dartmouth and would play football there.

Football star. Ivy-bound. From the outside, Hunter succeeded in maintaining the image of perfection. But signs of deeper problems emerged in high school.

The confidence he played with on the gridiron was contrasted by a palpable anxiety in other parts of his life. His family believes the internal pressure he put on himself prevented him from trying new things.

In Hunter’s teenage years, massive mood swings began. Once, Bill confronted Hunter about why there was a scuff on his truck. The simple question caused Hunter to erupt and nearly strike his father.

Hunter began having terrible nightmares in high school. His dreams were so troubling he could never describe them to his family.

His junior year, Hunter intimated he wanted to end his life. After several consults, a psychiatrist told the Forakers that Hunter would be safe.

Hanover

Hunter was eager to start the nearly 2,000-mile journey from Littleton to Hanover. Once on campus, he adjusted well and quickly made new friends. He was a standout on the Dartmouth JV football team where he resumed his role as a magnet to opposing ballcarriers. Hunter’s freshman year was a success, save for a brutal biology course that dashed his pre-med dreams.

Hunter suffered a concussion in training camp prior to his sophomore season. The Forakers don’t know the details of the injury, but they know the injury left Hunter with a constant headache. Hunter had seen many teammates come back too early from concussions and wanted to avoid the issues that plagued them. He elected to retire from football. The sport had done its job and helped to set him on the path he so desired.

Once Hunter no longer needed to be a hulking linebacker, he became obsessed with his body image. He weighed himself several times a day and had strict discipline about what he ate.

After graduating with a double major in Environmental Science and Anthropology in 2014, Hunter stayed in Hanover to work for Dartmouth’s alumni relations department. He was in a place that gave him great joy over the last four years, but boredom and loneliness set in without the people who he had experienced his undergrad years with.

In February 2015, Hunter called home. He was in a rehab program for alcoholism at a Dartmouth Hitchcock hospital.

“It was surprising because he was so in control of everything,” Kim said. “He was so in control of his body.”

Tough Love

Hunter moved to Utah in August 2015 to work as an expert gearhead in Salt Lake City. There, he advised people on all the outdoorsman activities he grew up with.

He was closer to home but further from who his family had always known him to be. The Forakers sensed Hunter was intensely ashamed of his alcoholism. The boy who could not tell a lie was now lying to his parents’ faces.

He told his family he had been diagnosed with bipolar disorder, depression, anxiety, and was on a myriad of medications. The Forakers don’t know how much of what Hunter told them was true. They do know Hunter spent much of his two years in Utah rotating between emergency room visits, rehab facilities, and detox centers.

In January 2017, Hunter called home to let the family know he was going to Durango, Colorado for a ski trip. They began to worry when calls and texts to Hunter went unanswered later in the weekend.

Kim arranged a wellness check from local police. Police found Hunter. He had the highest blood alcohol level they had ever seen. The Forakers learned Hunter went to Durango to drink himself to death. He survived the suicide attempt and was taken to a nearby hospital.

Following the attempt, the Forakers were at a loss for how to support Hunter. They sought professional counsel and were advised to implement a strategy of tough love with their son.

“It was the most difficult thing we have every done in our life,” Kim said. “Professionals were telling us on one hand to practice tough love and to not have any contact with him. But your heart is telling you to be a loving parent and to be there unconditionally.”

Hunter turned against his family and set out on his own back in Utah. For the first six months of 2017, Hunter was in a revolving door of sobriety, rehab, and halfway homes. Later, the Forakers found out Hunter experienced eruptions during this time like what they saw in high school.

“The Old hunter Again”

In July 2017, Hunter finally contacted the family. They visited him in Salt Lake City where Hunter was in sober living. For the moment, it seemed like Hunter had tackled his demons.

Hunter came back home to Colorado for a brief stay with his family in August 2017. He was clean. He wasn’t looking for scales to weigh himself. He had a new haircut and bought new clothes. He was happy. The Forakers were thrilled.

Hunter apologized to Kim for his suicide attempt in January. He promised he would never do that to her again.

“I vividly remember telling Hunter that I was so proud of him,” Jordan said. “Because I did not want to have to tell his nieces and nephews one day that they did not have an uncle if he circled back into his behavior.”

Hunter found a job in Dallas, near where Jordan was attending school in Lubbock. Jordan and Kim came to Dallas to help Hunter decorate his new apartment. They left Hunter with smiles on their faces and hope in their hearts.

“Hunter was confident and looking forward to a new start,” Kim said. “We hoped that a new environment would be exactly what he needed.”

“That Sickening Feeling”

Hunter’s first week at work in Dallas went great. He told his family he loved his job and was jockeying to see if he could get Jordan a position there upon her graduation from college.

He reached out to his family on Thursday, September 14. If there was a problem, the Forakers couldn’t tell by how Hunter sounded that night.

But texts and calls slowed and then eventually stopped, just as they had when Hunter was in Durango.

“We definitely had that sickening feeling that something was wrong,” Kim said.

Hunter didn’t show up to work on Friday and had started drinking again. On Monday, September 18, 2017, Hunter Foraker died by suicide. He was 25 years old.

The Forakers’ Message

The Dallas coroners’ autopsy on Hunter’s brain found evidence of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE). Perplexed, Kim Googled the degenerative brain disease. Within 30 minutes, she was on the phone with Lisa McHale, CLF’s Director of Legacy Family Relations.

Lisa guided Kim through the brain donation process at the UNITE Brain Bank. Months later, Brain Bank researchers validated the results of the initial autopsy. Hunter was diagnosed with Stage 2 (of 4) CTE.

The diagnosis helped explain Hunter’s erratic behavior, sleep disturbances, mood swings, and substance abuse. Learning Hunter had CTE set the Forakers off on their own research journey. They knew about concussions, but they learned how repetitive nonconcussive impacts catalyze the formation of CTE.

The potential dangers of nonconcussive impacts have changed the family’s view on youth tackle football. Hunter’s youth tackle football career had once brought the Forakers immense joy. Now, the family advocates for Flag Football Under 14.

“Please don’t let your youth play tackle football,” Kim said. “Hunter began playing football at the age of seven and stopped playing at 19. He would have sustained substantially fewer nonconcussive hits if we would have not placed him in youth football and waited to place him in football until his brain was fully formed.”

Kim didn’t know about CTE until after it was found in Hunter’s brain. The family hopes doctors working with former football players struggling with mental health symptoms or addiction consider CTE as a possible cause of their problems.

“Every time Hunter expressed he felt crazy, people brushed it off,” Jordan said. “When he started to drink heavily, it was the easy thing to say he was an alcoholic. When in reality, it was something much, much deeper that needs to be validated and explained.”

Three years after his death, the Forakers remember Hunter for his humility, kindness, and drive. They remember Hunter’s hugs, not his tackles.

“He gave the best bear hugs,” Kim said. “When he held your hand, you felt the love exude from his body.”

Suicide is preventable and help is available. If you are concerned that someone in your life may be suicidal, the five #BeThe1To steps are simple actions anyone can take to help someone in crisis. Learn the steps at BeThe1To.com.

If you are struggling to cope and would like some emotional support, call the 988 Lifeline at 988 to connect with a trained counselor. It’s free, confidential, and available to everyone in the United States. You do not have to be suicidal to call.

Are you or someone you know struggling with lingering concussion symptoms? We support patients and families through the CLF HelpLine, providing personalized help to those struggling with the outcomes of brain injury. Submit your request today and a dedicated member of the Concussion Legacy Foundation team will be happy to assist you. Click here to support the CLF HelpLine.

Buxton Fowler

Frederick Douglas France Jr.

Jason Franklin

It had been a tough four months. Something was going on with our only child Jason, and we did not understand it. Our happy, popular, life of the party, college football-playing kid was suddenly experiencing all sorts of “crazy” emotions and physical reactions. Rage, depression, paranoia, sleeplessness, and severe headaches. He was closing himself off from friends. What was causing this? What should we do? As the issues progressed, he moved away from us in Southern California to Arizona. But we did everything we could to continue to help him. He came home the weekend of June 30 and then again the weekend of July 4. On that second weekend, he seemed to be doing a little better. He even got a gap in his teeth fixed. Then on the night of July 14, 2018, just five days after he left to go back to Arizona, our doorbell rang. It was a police officer. She told us our son was found dead in his bathroom in Arizona. It was the end of our lives. Our only child was gone and with him, our future. A future without my son, without grandkids, without the dreams I had that were so deeply woven into the thoughts that swirled in my heart and mind.

The happiest, funniest person I knew

Jason Garrett Franklin was born May 6, 1992, in Los Angeles, California. He came into this world the happiest baby bringing joy to everyone around him. He didn’t cry much. He just laughed and smiled. Everyone told me how lucky I was.

Jason was the most social person I think I have ever met. He and I shared the gift of gab and the desire to entertain and engage everyone we met. Jason entertained everyone constantly, whether it was one on one or in crowds. He had his goofy impressions, crazy dance moves, amazing stories, and hysterical high-pitched laughs.

His vice principal at Chaminade College Preparatory School in Los Angeles told a story about how whenever he would have a prospective family walking with him around Chaminade, he would seek Jason out. Jason would introduce himself and spend the next several minutes telling them about the school, the teachers, the students, you name it. I am sure he convinced many a family to bring their children there. He could truly talk to anyone about anything.

Sports and football

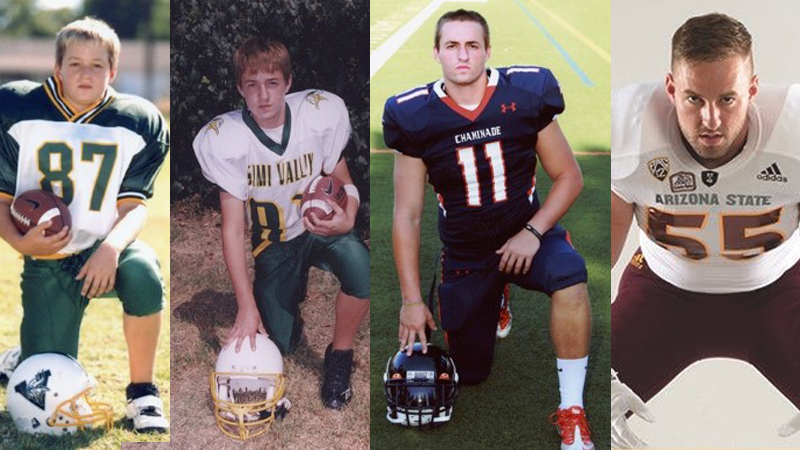

Jason loved sports. He played so many, but baseball and football were his favorites.

He played baseball from the age of two through 18. Like everything else Jason did, he jumped right in to T-ball. He had no shyness at all. He walked up to the four and five-year-old’s in the program and introduced himself. In the outfield Jason would jump up and down with the same joy and happiness he maintained throughout his life.

During Jason’s final year of youth baseball, his 13 year-old all-star team made it to the Pony World Series before losing 1-0 to Puerto Rico in the finale. Jason was crowned the World Series batting champion.

In high school, Jason played for the Chaminade Eagles baseball team. He loved his teammates and had the greatest time in the dugout motivating and inspiring them.

Baseball was great, but Jason fell in love with football. He believed it was a better fit for his personality. He loved the camaraderie, the importance of working together as a team and the thrill of making big plays. I loved to watch him play, but I was always afraid he would get hurt.

Jason had such joy and excitement on the field. He’d boisterously rejoice every time he made a big play. Half the time he would get warnings by officials to manage his celebrations, but light reactions were not in his nature. Jason’s high school teammates loved his halftime speeches. Only they know what he said, but I am sure he was motivational and made everyone smile in the face of any second half adversity.

Jason received scholarship offers from small schools to play football, but he wanted to be a part of something bigger. He chose to walk on at Arizona State University after being contacted by a linebackers coach. We supported his decision as we saw how much it meant to him to be a Sun Devil and play in the Pac-12. It was his dream come true.

At ASU, Jason’s personality was on full display. His natural charm landed him roles in front of the camera as a host and entertainer with shows such as “Franklin Knows Best.” He created his own blogs, “Pregame at Franklins” and “Excuse My Moderation” where he discussed his opinions on all sorts of subjects. “Franklin Knows Best” was my favorite. It was a feature show on NBC 12 Sports in Phoenix. It was Jason at his best, coaching a girls’ powder-puff football team, interviewing kickball players, trying out for the Phoenix Mercury practice squad, riding in a supped-up car on a track, dressing up and throwing axes at the renaissance fair. The station put him in many bizarre situations, and he was hysterical every time. You can see examples of Jason’s work at www.jasonfranklin55.com.

At ASU, Jason was a scout player for much of his career. Most scout players quit because they get inferior equipment, they aren’t respected by the coaches, and they take abuse with little shot at playing time. But Jason did not quit. Jason knew his job was to make the team better. There was no glory in it for him. It was about his team. Of course, Jason was not completely selfless. He did yearn to be recognized for his efforts. He was ecstatic when he earned a scholarship from ASU in his junior season.

“There are no words that I can explain. All the work we have put in. All the hours. Some of these guys, they get their school paid for. We did it voluntarily because we love this game,” said Jason at the time. “To be a walk-on on this team for as long as we have, you got to look at it as a game and you got to love this game or else you won’t survive.”

Our last football memory with Jason came at Jason’s last ASU football banquet following his final season. During the banquet, the various MVP’s were named. Then the Glen Hawkins Award for Scout Player of the Year was announced. We could tell from the speech that the award winner was going to be Jason and our family became extremely excited. When they named Jason as the winner, we stood up and cheered and then to our utter amazement we saw the entire ASU football team stand up and cheer more for Jason than they had for any other player that night. It was evident how my son was beloved and respected by his teammates.

The injuries

Jason was lucky with injuries in his youth and high school football career. That luck changed in college.

Jason suffered one concussion during his first couple of years at ASU. Then in August 2014, just after receiving his scholarship, Jason suffered a severe concussion. At the time, a company named TGen had been placing sensors in football helmets to track the impact of concussions through blood and urine analysis. After Jason’s concussion, he was told it had been the worst hit they had recorded. They also noted his blood and urine counts were the highest they had seen in any athlete after a concussion.

Jason was taken out of play for about a week. A week later, he was put back in and almost immediately sustained another concussion. We’ll never know if this was really a new concussion or further damage associated with the original concussion. He was taken out again for a couple of weeks. Once again, right after he was put back in, he sustained a third concussion. After this last concussion, he was really hurting. He was taken out of play for about a month.

After the third concussion, I was concerned the team should not let him play again and he went to see his team neurologist. The team neurologist indicated Jason had passed all the tests and was clear to play. The decision was up to Jason. Of course, Jason wanted to play and so it was. He played two more seasons after that. To this day, I believe the doctor and coaches should have stopped Jason from playing again.

Jason’s friends noted his personality changed for about six months after this series of concussions. In fact, Jason also noted this in a Cronkite School News documentary and in an ESPN special on concussions.

Jason’s last four months

It was Easter Sunday 2018 when we first really noticed an issue. We took Jason to brunch. He hardly ate anything. He seemed very agitated. Our conversations with him over the next several weeks were very difficult.

Then on April 29, things seemed to completely go off the rails. We were going to Jason’s house in Arizona to meet him for lunch. When we arrived, we discovered he left the house through a window in the bathroom. He did not arrive back home until about 6 p.m.

We came back when we heard he was home. We found multiple neighbors standing outside around the house. Jason came running out of the house telling me his roommate had a gun and was trying to kill him. The police were called. They believed Jason was suffering from some sort of psychotic episode and suggested we take Jason to the hospital immediately. We tried to persuade him but he refused to seek help.

We took Jason back to our house in California. He ate a little and then went to sleep. Not too long afterwards, Jason woke up and started saying his dad was going to kill him. He said he heard us talking. He started to get more and more agitated. He was enraged and telling us he would kill us first so we couldn’t kill him. We kept telling him that we loved him and would never hurt him. Given Jason’s size and strength, I knew we could be at risk, so, I dialed 911. The police talked to Jason and decided to put him on a 5150 hold, which is a three-day hold to ensure a person is not violent or suicidal.

The day after Jason was released from the hold he decided to go back to Arizona. I tried to stop him, but he was determined to go.

About three weeks after Jason returned to Arizona, he began having headaches and started hearing siren-like sounds in his head. He went to the hospital, but doctors could not detect any issues.

In early June 2018, we noticed Jason was spending less and less time on social media and stopped all of his blogging and video activities. He was also not returning calls to his old producer who was trying to get him to start the “Franklin Knows Best” segments again. He stopped responding to e-mails. He missed one of his best friend’s weddings. We talked with him consistently during this time and even drove to Arizona a few times. But he continued to say he was OK.

“I’m just a little tired,” he’d tell us.

Our concern grew as we saw his agitation and anger level growing. Jason was seeing a psychiatrist, but the psychiatrist said he saw no signs of mental issues other than normal growth concerns for Jason’s age.

Jason returned home to California for both the weekend of June 30 and over the Fourth of July weekend. He seemed more withdrawn than ever and would get lost in long, blank stares. He was not sleeping well. He was having memory problems. He had no money and couldn’t remember how to get more money out of his bank account. He would go for long walks to try and calm his head.

He returned back to Arizona on July 9. A couple of days later he cancelled a date with a girl via an odd, nonsensical text. On the evening of July 13 he went walking at 11:00 p.m. and did not return until sometime the next morning on July 14. After returning, his roommates said he seemed fine. Both of them left the house and sometime after they left, Jason took his life. According to the toxicology report, Jason had no drugs or alcohol in his system at the time of his death.

The diagnosis

After Jason passed away the coroner in Arizona, who was familiar with Jason’s history, recommended we donate Jason’s brain to Boston University to be analyzed for Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE). It was at that point that everything started making a little sense. Could this have all been a result of injuries he sustained playing football?

Dr. Ann McKee, Director of the UNITE Brain Bank, performed the brain pathology analysis. She found Jason was suffering from Stage 2 (of 4) CTE with nine CTE lesions throughout multiple parts of his brain.

When Dr. McKee did the initial Coronal dissection, she noted Jason had something called a Cavum Septum Pellucidum (CSP). It had deteriorated along with the space present between the two sides of his brain. CSP is one of the distinguishing features of individuals displaying symptoms of CTE.

The CTE damage was mostly in the frontal lobes of the brain that control impulse, judgement, violence, aggressive behavior, depression, and suicidality. Dr. McKee indicated the disease was advanced and shocking for a 26 year old. The pathology report showed the nine CTE lesions in Jason’s brain were easy to see and were found in the motor cortex, superior frontal cortex, inferior frontal cortex and dorsal and lateral frontal cortex. Dr. McKee noted that Jason had probably been suffering for longer than we were aware.

Football is now a conundrum for me. We have always loved to watch the sport. But, given that football was a major contributor in my son’s death, how can I still love and watch this game?

Jason loved the sport of football from the core of his being and he would be devastated if he found me trying to do things to end the sport. So, as I begin my search for a new purpose in life, I have to keep in mind both what my son would have wanted me to do against my own feelings about the game and its impact on our family. I am certain that I will work to seek changes in football, especially by advocating for youth athletes to play flag football instead of tackle football. I will also support those who are trying to better understand, diagnose and treat CTE and, of course, I want to help further enhance concussion protocols, hit counts, treatment of scout players, and advocate for better rules regarding forcing medical retirements.

I vow to do all of this, but to work to eliminate football entirely, that I cannot do. It would break my son’s heart.

A way to move forward – I Got You Day

Jason lived his life trying to make a positive difference to everyone he met. His vibrant personality allowed him to command every room he was in. He loved people and was always there for his friends and family.

It was important for us to honor Jason’s life through positivity. One of Jason’s favorite sayings was “I Got You.” He used it all the time for so many positive reasons. In honor of Jason, we decided to celebrate his birthday of May 6 each year as “I Got You” days. Each May 6, we will spend the day trying to help others and trying to show them that there are people out there who “got them” and are there to help get them through their day.

Our first “I Got You” day was in 2019. Our family delivered clothes, food, personal care items and toys to homeless shelters, to homeless people we encountered on the streets, to animal shelters, to food banks and to children’s hospitals. We asked our friends and family to help spread the “I Got You” spirit and they delivered beyond our expectations. We will continue “I Got You” day every year and promise it will grow and grow.

Jason, dude, I will miss you and love you for the rest of my life. I promise to keep your spirit alive until we are reunited. Just know, “I Got You.”

Suicide is preventable and help is available. If you are concerned that someone in your life may be suicidal, the five #BeThe1To steps are simple actions anyone can take to help someone in crisis. If you are struggling to cope and would like some emotional support, call the 988 Lifeline at 988 to connect with a trained counselor. It’s free, confidential, and available to everyone in the United States. You do not have to be suicidal to call. If you’re not comfortable talking on the phone, consider using the Lifeline Crisis Chat at www.crisischat.org.

John Frechette

Ryan Freel

Luke Frey

As a child, Luke loved anything that was blue, and it just so happened his favorite animal was a lion. One Sunday while watching football with the family he discovered the Detroit Lions and became enamored with Barry Sanders and the game of football. He spent the rest of his life dedicated to the game, and he told everyone he “bled Honolulu Blue.”

Luke was a great all-around athlete from a young age, playing baseball, soccer, basketball, ice and street hockey, running track, and of course football. He played wide receiver, tight end, safety, and wherever else the coaches needed him. Later in his career, he focused on kicking. He was a four-year Varsity player for the Fair Lawn High School Cutters, and he went on to join the team at Pace University, where his football career ended.

During his life Luke suffered numerous injuries, and a majority of them were to his head. He was eight years old when he suffered his first concussion while rollerblading. The next two happened during junior football, the second of which involved him being taken off the field in an ambulance. Two more concussions came in high school, the first by sliding in a high school baseball game and another from a hard hit during a football game. His final concussion took place in college and ended his playing career for good. When he lost football, he started to lose himself.

This could not have come at a worse time. The loss of football was followed by the loss of our father, a man of many hats. Among his roles were the Superintendent of Parks and Recreation, a Board of Education member, basketball and baseball coach, and his favorite role: dad. Our dad always found ways to give back to the community and his family. Losing a parent is hard enough, but when you lose someone who believes in all the potential you have in this world and who you idolize more than anything, you succumb to the negatives in life. Luke sunk into a depression, left school, and dealt with frequent headaches and the frustrations from short-term memory loss.

After losing himself and the opportunity to play the sport he loved so much, Luke turned to coaching. He volunteered to coach a Pee Wee football team in his hometown’s football association. This brought a light to Luke’s eyes we hadn’t seen since he had to give up playing the game himself. Luke chose to coach because he knew if he could not play, the next best thing would be to educate the younger generations about a game that meant so much to him. Not only did Luke coach these kids, they would reach out to him during the offseason just so they could get a workout in or spend time with him at the fields. When Luke stopped being involved in the town’s football association, he began to lose himself a bit more.

Luke was always the happy-go-lucky, funny, charming, class clown with a heart of gold. He was liked by everyone and would give you his last dollar. He was full of love and laughter and brought joy to those around him. He was both a brother and best friend to his three sisters and did everything with his family.

But over time, he became more depressed and angry. He had difficulties comprehending what he was reading and would have to reread a paragraph multiple times. He would have to rewind the same scene on the TV over and over until he could move on to the next. He could go from being calm to punching a wall within seconds when something suddenly set him off.

This led him down a dark path in which he chose to self-medicate to ease his headaches, help him sleep, and stop the voices he was hearing that told him he was worthless. Self-medicating led him to harder drug use and eventually he started sleeping all day, couldn’t hold a job, and broke relationships with those closest to him. He finally hit rock bottom and went to rehab. He cleaned himself up for a few years and then relapsed before going back and getting sober.

Luke then met his amazing fiancé Emily and became a dad to Meadow. Meadow became his reason for living and he was his happiest being a dad, even if it was for a short time.

Even when he was happy, Luke told us all that there was something wrong with him. Always a football fan and reading every article and watching any documentary that pertained to the sport, he learned about CTE and researched it further. He felt he had some of the symptoms and was frightened for his future. He always made it known to his family that he knew he was not long for this life and that if something should happen to him, he wanted to donate his brain tissue for CTE research. He wanted to be a part of the research, to help find a way to show its effects, to help prevent it, to help find treatments, and most importantly to help those who love sports be able to play them safely.

During his final days, our family discussed his wishes and called Boston University to see what steps needed to be taken before we lost him. I like to believe that donating to the UNITE Brain Bank was Luke’s last wish and it was my job to help him achieve it. On January 3, 2019, Luke passed away of a stroke. He was 31 years old.

Thirteen months after his death, we learned Luke was diagnosed with Stage 1 (of 4) CTE. While there are still many questions and possibilities about whether or not his diagnosis helped contribute to his mental health issues, his drug use and his death, it is reassuring to know there was something that may have changed him from the boy we knew. I felt a huge relief and closure for Luke, knowing that he was right, that he knew his body and knew this could be why he chose to donate, and that he wanted his legacy to be one that could help bring awareness to young athletes like himself.

We hope if anyone takes anything out of Luke’s story it’s to know how much he loved his friends, football, and his family with everything he had. We also want others to not give up on loved ones who’ve suffered from concussions and head trauma. They are invisible injuries with effects that are hard to quantify. We do not know what they are going through mentally, how they’re thinking, how they’re feeling, or what type of pain they are suffering from. We need to stop pushing them to get back to their sports before they are healed enough to do so. Concussions aren’t to be taken lightly. What should matter is the health of each athlete.

-Written by Katie Frey (sister) on behalf of Joan Frey (mother), Maggie Quinn (sister), Kasey Frey (sister), Emily Costello (fiancé) and Meadow Frey (daughter)

Luke also leaves behind his nephew River Frey and nieces Peyton Quinn and Reese Pinsdorf, brother in laws John Quinn and William Pinsdorf, and his Aunt and Uncle Kathleen and Peter Drozd.

He was predeceased by his father George Frey, and a local scholarship is given each year in their honor for young athletes who have dedicated their time to coaching, working, or volunteering for the community.

George and Luke Frey Memorial Scholarship

28-06 Madison Terr

Fair Lawn, NJ 07410