John Henry Johnson

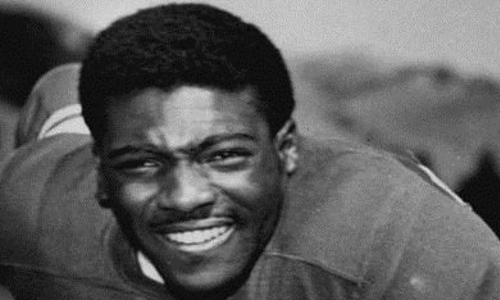

John Henry Johnson’s remarkable journey started in 1929, in the rural town of Waterproof, La. In the segregated South, Johnson did not have the option to attend high school near his hometown, so he moved to the Bay Area to live with an older brother at the age of 16. At Pittsburg High School, Johnson played organized sports for the first time, putting together a dominant prep career as a football, basketball, and track and field athlete.

Upon graduation in 1949, Johnson chose to play football at nearby St. Mary’s College, where he made history a year later as the first Black player in program history. He was the first Black student-athlete to compete against a University of Georgia team and was carried off the field by the home fans following a standout performance in a stunning 7-7 tie against the visiting Bulldogs.

St. Mary’s discontinued its football program after the 1950 season, prompting Johnson to follow several teammates transferring to Arizona State, where he continued to play on both sides of the ball in addition to returning kicks. The San Francisco 49ers selected Johnson in the second round of the 1953 NFL Draft, and after one season in the Canadian Football League, the fullback embarked on a legendary NFL career.

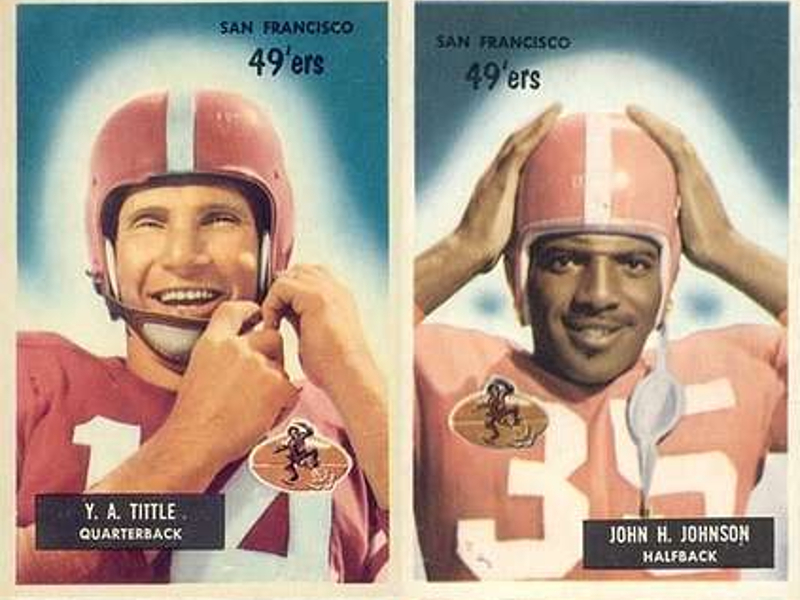

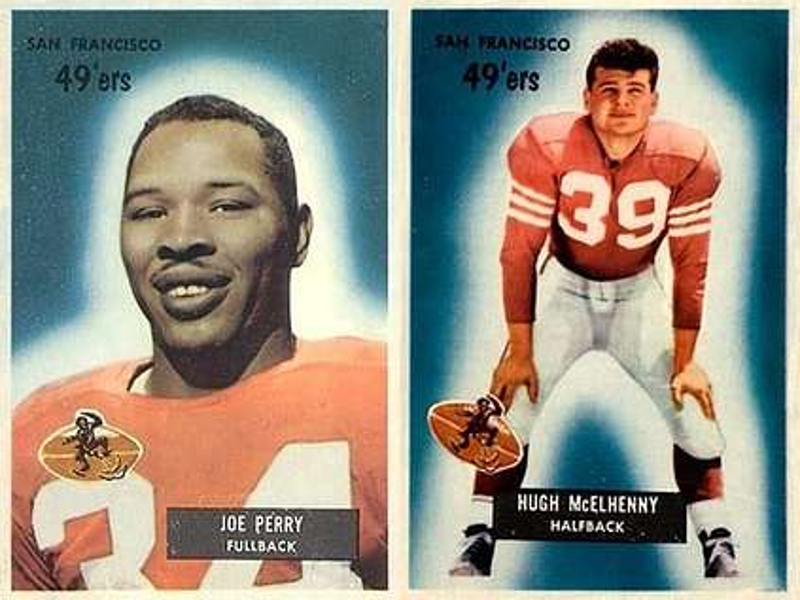

In San Francisco, Johnson joined quarterback Y.A. Tittle and running backs Joe Perry and Hugh McElhenny to form the “Million Dollar Backfield.” The four backfield mates captivated Niners fans for three seasons and are the only “T formation” fully enshrined in the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

John Henry Johnson was one of four Hall of Famers making up San Francisco’s “Million Dollar Backfield.”

As his on-field success raised his nationwide profile, Johnson enjoyed raising his family when he had time away from football. John Henry’s daughter Kathy Moppin said her father loved to dance and always had a joke for his six children. She said he was proud of his place in the Bay Area community and enjoyed visiting schools with his 49ers teammates.

Kathy said because of her father’s playful demeanor off the field, she did not realize until late in his career he developed a reputation as one of the toughest players in the NFL, frequently sacrificing his body on crushing blocks and bruising runs between the tackles.

“He got hurt quite a bit,” Kathy said. “I can remember he had teeth knocked out and shoulders dislocated, and back then, they used smelling salts when they got lightheaded on the field. He went through a lot of trauma to his body.”

The 49ers traded Johnson to Detroit before the 1957 season, and that year he helped lead the Lions to their most recent NFL championship. Johnson joined the Pittsburgh Steelers ahead of the 1960 season. Though he was 31, Johnson still had his best individual seasons ahead of him. He earned the final three of his four Pro Bowl honors in his mid-30s. In 1964, at 35, Johnson became at the time the oldest NFL player to rush for 1,000 yards in a season.

When Johnson retired at 37 following the 1966 season, he ranked fourth on the all-time rushing list. He finished his career with the Houston Oilers but returned to Pittsburgh to start a new career with Columbia Gas of Pennsylvania and later with Warner Communications. Year after year, the Pro Football Hall of Fame overlooked Johnson, who was considered by peers to be one of the best all-around running backs in NFL history.

Finally, in 1987, Johnson got the call to Canton, joining his “Million Dollar Backfield” teammates in the Hall of Fame. He joked at the time that the nickname was far from literal, as he never earned more than $40,000 in an NFL season.

Back in the Bay Area, Kathy said she would speak with her father on the phone two to three times per week. However, when John Henry reached his 50s, Kathy and others close to John Henry noticed changes in his willingness and ability to communicate, on the phone and face to face. A friend in Pittsburgh called Kathy and encouraged her to check on her dad, which she did with the help of John Henry’s wife Leona.

“He still had a good sense of humor, but he was just a lot slower,” Kathy said. “It took him a while to answer if you asked him something. I noticed early on he was having some symptoms of something. I didn’t know what it was.”

In 1989, with Johnson’s cognitive issues affecting his daily life, Leona enrolled Johnson in an Alzheimer’s disease study in Cleveland. This led to a formal diagnosis, and Johnson retired from his post-playing career. Kathy said it was a difficult time for their family, with most of them more than 2,000 miles away from their dad.

“I was very sad, and my siblings were sad, too,” Kathy said. “My dad, at that point, didn’t really get a sense for how serious things were.”

Kathy said despite his struggles at home, John Henry looked forward to annual trips to Canton, Ohio for Hall of Fame induction ceremonies. Clad in their gold jackets, Johnson and his fellow Hall of Famers cherished the opportunity to reminisce about the glory days of decades past.

As the years went on, Kathy said, the late-summer tradition became an eye-opening experience for her family and other relatives of NFL alumni. In Canton, she recalled more wives, sons, and daughters privately sharing concerns about their loved ones’ health years after their football careers ended.

“Every year when I went back, there was more and more guys having symptoms like my dad,” Kathy said. “That’s what got me. Every few years, I could see the next husband with symptoms and the wife having to push him in a wheelchair.”

John Henry returned to California after his wife passed away in 2002. Kathy became his primary caretaker, which presented challenges she could only face with help from her husband and siblings.

“When you sign up for that, you don’t know how hard it’s going to be and how it changes your life,” Kathy said.

Then in his 70s, John Henry struggled further with memory and communication. Though it had been 50 years since he played for the 49ers, he still received fan mail from fans in the Bay Area. When he signed autographs, Kathy said she had to remind him which year to write under his signature when he mistakenly wrote the incorrect year of his “HOF” induction.

Johnson’s struggles with Alzheimer’s included a few instances of wandering from home, which only added stress to Kathy as a caretaker. She said she installed a bell on her front door after police returned her father, finding him waiting at a nearby bus stop. He told her he was on his way to join his Niners teammates for practice that afternoon.

“It was hard for me,” Kathy said. “It was sad to see him decline like that. I cried many a night. But all my siblings helped out, and I was able to get through it. It was sad to see.”

John Henry Johnson died in 2011 at the age of 81. At the time, the NFL’s concussion crisis and the growing understanding of CTE led Kathy to consider donating her father’s brain for study. His San Francisco teammate Joe Perry had died five weeks earlier, and with encouragement from Joe’s widow Donna, Kathy elected to donate her father’s brain to the UNITE Brain Bank.

Boston University researchers diagnosed Johnson with stage 4 CTE, the most advanced stage of the neurodegenerative disease.

“It kind of gave me some closure,” Kathy said. “I was very shocked and sad to hear that, but then I understood more why my dad acted like he did.”

Kathy shares her father’s Legacy Story to celebrate his life while raising awareness about the potential long-term consequences associated with tackle football’s repetitive head impacts. While helmet technology has improved, Kathy said today’s players face most of the same risks as her father, and she hopes more parents and coaches educate themselves about CTE to help prevent similar outcomes to what her family experienced.

She hopes her father’s story leads coaches and administrators to consider policies and rule changes with long-term brain health in mind. Kathy and her family remember John Henry Johnson as a “loving, kind, funny guy,” a man who put smiles on the faces of fans from coast to coast.

“I was shocked to see so many people still remembered my father, and they remembered him as a hard player, a tough player,” Kathy said. “He loved football, and he was loved by his family.”

Ron Johnson

Tom Johnson

On the morning of February 8, 2015, I received the call from Tom’s wife. She told me Tom was gone. At first, I thought she meant he had left. I guess in a way he did. He left in the middle of the night and escaped the demons that haunted him during the latter years of his life.

Tom was the youngest of my three boys. He grew up in Brockton, Massachusetts, which is known as the “City of Champions” because boxing legends Rocky Marciano and Marvin Hagler grew up there. Tom’s father left our family without notice when Tom was only three years old. Despite growing up in a single parent home, there was no shortage of love from myself and his two protective older brothers, John and Dave. Tom and his brothers were gifted athletes at an early age and played baseball, football, basketball and several other sports. As a single mom working multiple jobs, I was thankful for athletics to keep them busy and largely out of mischief. I could never have envisioned Tom’s gift for all sports, particularly football, would contribute to such a marked demise in his quality of life and a premature death. It’s a parent’s worst nightmare, and I will always struggle with this guilt.

In addition to being a gifted athlete, Tom was an outstanding high school student, a member of the National Honor Society, and a very well-liked person. The combination of his athletic and scholastic talents made him stand out to his friends, teachers, teammates, and to his renowned high school football coach, Armond Colombo. Tom had strong beliefs about right and wrong, and he developed many lifelong friendships growing up in Brockton. Tom was an unconditional friend and his friends’ battles were Tom’s as well. His confidence and lack of pretense enabled him to converse with a homeless person just as easily as he could with President George H. W. Bush, who he met while attending the President’s Cup golf tournament.

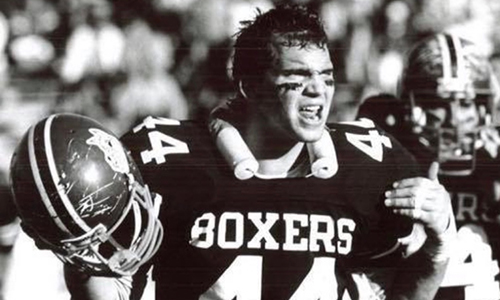

Tom played on the varsity football team as a freshman and was a star player each of his four years. This was a significant achievement considering the rich football history at Brockton High. The team went on to win three Massachusetts High School Super Bowl’s during the four years he played, losing only one time in his four seasons. Tom was co-captain and team MVP his senior year and named to the Enterprise All-Scholastic honors and selected to the Shriners All-Star team. Posthumously, Tom was inducted into the Brockton High School Hall of Fame in 2015.

Tom occasionally played fullback, but his primary position was middle linebacker. Tom loved battles, and at this position, he could outsmart, anticipate and use his speed and strength to tackle opposing ballcarriers. “It’s a gridiron war,” he and his teammates would often say. His teammates gave Tom the nickname “Captain Crunch” because he played with such reckless abandon to ensure his helmet connected with the ball carrier. Back then, Brockton players often compared helmets to measure who had collected the most dents and scratches throughout the season. The more damaged the helmet, the better. Tom’s helmet was frequently the most damaged.

During his high school football career, Tom suffered many “bell-ringers,” as they were called then. These were frequent, and not taken seriously by Tom, his teammates, or any of us. During one game against a team from New York, Tom suffered an especially serious concussion and was taken by ambulance to the hospital. Despite being diagnosed with a concussion on Saturday, he was back at football practice on Monday. During Tom’s high school years, 1985-1988, concussions weren’t newsworthy or ever a deterrent to sports.

Tom was offered several scholarships from various colleges and universities. He decided to attend Colgate University in Hamilton, New York. He played less in college than in high school, primarily due to a poor relationship with his coaching staff. In a game against Army his junior season, he suffered another serious concussion. He was not examined and diagnosed until several days after the impact and was sidelined for the next game. Soon after, people close to him noticed escalations in certain behaviors and we became concerned with his mental health.

Tom was always excitable and prone to fights, but after that concussion he became more erratic and he frequently escalated minor conflicts. He began drinking more often and acting out in ways that occasionally resulted in property damage and fights. At one point during his senior year, he was asked to take a leave of absence from school after an unprovoked altercation. Previous attempts by a girlfriend to get him to engage in therapy at school counseling sessions were short-lived. When Tom came home to be with his family for that year off from college, he told us about a traumatic incident that occurred during his childhood. After that admission, he willingly participated in therapy sessions and seemed to be on a great track as he returned to Colgate to complete his senior year and graduate in 1993.

After college, Tom moved to New York City and became an assistant specialist on the American Stock Exchange with the prominent firm Spear, Leads & Kellogg. He was considered such a prodigy at auction market trading that he was assigned to support one of the ASE’s busiest and most high-volume stocks: Motorola. After several years in New York, he realized how much he missed his family and friends and decided to move back to Massachusetts where he found work with Citigroup in their analyst program.

It was after a trip to Ground Zero to volunteer after the events of September 11, 2001 that Tom surprised everyone with his decision to enlist in the Marines. No one could have stopped him; he was incredibly determined to serve his country. In 2002, Tom departed for boot camp at Parris Island, NC before being deployed to Iraq. He served honorably on special operation tours and was awarded several commendations, including a Global War on Terrorism Service Medal, the National Defense Service Medal, and a Medal of Good Conduct.

Tom was discharged in 2006. Despite his commendations and awards, Tom was severely affected when he came back home. His behavior was erratic and irrational, his drinking was excessive, and his tendency to resort to violence escalated. He no longer resembled the incredibly loving son, brother, uncle, and friend we all knew. We were all concerned for him.

His condition grew worse with each passing year. In 2007, Tom attempted to take his own life. He was taken to a local hospital and then transferred to the Brockton VA Hospital for observation and treatment. He remained there for two weeks. He worked hard to convince his treating psychologist that he would be OK with outpatient therapy and he agreed to go to AA meetings. He seemed to be getting the help he needed and returned to spending time with friends and family. For these reasons, we saw the attempt to end his life as an aberration and not something we would ever revisit again.

Soon after, Tom received a job offer to work at the Naval Academy Prep School (NAPS) in Newport, RI. For a few years at NAPS, he was at his happiest professionally and seemed to be on the most positive trajectory. He worked as a system engineer and volunteered as an assistant football coach, mentoring kids who he truly loved. He also obtained a Master’s in Science Communication from Stayers University in Virginia. All seemed to be going great for Tom and I had never seen him happier.

The changes began to creep into our lives so slowly it’s difficult to pinpoint exactly when they began. Perhaps the first blow can be tied to when the chain of command at NAPS changed and Tom was informed his position and coaching role would be eliminated, along with his assistants. He was living away from home, so I did not see him enough to notice any day-to-day issues. Following an altercation at his brother’s home, he admitted himself to a drug and alcohol rehabilitation facility on Cape Cod. He maintained a position with NAPS, but they were now aware of his struggles and were initially very supportive to his illness.

Next, Tom bought a home in Middleboro and invited his fiancée and her son to live with him. They married shortly afterwards. Over the next two years he and his wife participated in AA programs, but would continuously relapse, rehab, and relapse again. He lost his job and his home life was volatile and unstable. For a while, Tom was very open to receiving help. Around this time though, he became more rigid in what treatments he would participate in. He did try a long-term rehab program at the VA where he was diagnosed with PTSD. Doctors also considered a bipolar diagnosis and he was given medication. At that time, no one knew the true cause of his suffering.

A physical altercation then led to jailtime for Tom. After he was released, he seemed to lose all enthusiasm for life and his fighting spirit. An athlete who loved engaging in physical activities no longer cared about exercise or maintaining a healthy lifestyle, allowing his overall health to deteriorate. Most notably, he cut off communication with lifelong friends and family, essentially anyone who was trying to help him help himself. His lifetime of sociability and gregariousness contrasted with his devolution into reclusive behavior. His close relationships with his two older brothers whom he idolized became contentious, fraught with tense accusations, and even violent.

In December 2014, Tom called me crying to say he believed he was dying. We had the Middleboro police go to his home and escort him to the Bedford VA hospital. Tom called me after arriving to thank me for saving him, but he asked that I not visit since he had a lot of thinking to do. Sometimes that conversation haunts me. I questioned whether I should have overruled his request and gone to visit him. I was entirely unaware that he left the hospital and the program he was enrolled in until I received the call that he had died. Though I told him countless times during his difficult years, I never got the chance to tell him then how proud I was to be his Mom. I never got to remind him how I still loved him to the moon and back and always would.

During the final years of Tom’s life, he did his very best to tackle the mental pain and anguish he suffered like he had when he was a football player. He would often complain of excruciating headaches and say how he couldn’t rein in painful, rambling thoughts. We attributed the symptoms to Tom’s tendency to overthink or to his alcohol abuse. Even when he didn’t appear to be trying, Tom was fighting an internal battle with his entire being, a battle within that was unwinnable – mentally and physically. There were times when we thought he was getting better, but it wouldn’t last. None of the numerous hospitalizations or stays in rehab facilities to recover his life could bring Tom back to a place of calm or equilibrium. His life became what he described as an unrecognizable, living hell.

A few times when I went to his side and held him, he would ask me to please pray with him and his prayer was always the same, “Mom, please ask God to bring me home. I don’t want to live like this anymore.”

At the time Tom passed away, our family knew very little about CTE until his brother-in-law, Kevin Haley, notified us about the Concussion Legacy Foundation. He suggested we donate Tom’s brain to be studied for Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy, or CTE. We decided to donate his brain, and about a year later, researchers at the UNITE Brain Bank diagnosed Tom with CTE.

I will always be extremely grateful to Kevin for providing this information and helping us complete the brain donation process. Learning about CTE has changed our lives and aided us in our grieving process. Gaining an understanding of what was happening within my son’s brain helped us understand those years where we could not comprehend his changes. We just wish we had known sooner, before it was too late to make a difference for Tom. The most important thing now is to continue the work and to expand the awareness for other families experiencing what we did and provide them with hope, and measures they can take for someone they love.

I want to extend my heartfelt thanks to Lisa McHale and Dr. Ann McKee and the entire research team for their painstaking diagnosis and patient explanation of the pathological findings. For me, my family and everyone else who loved Tom, the CTE diagnosis helped explain the devastating effects on Tom’s life and greatly assisted us in healing from his death.

Tom is missed every single day, but no longer are our memories fixated on the events of those traumatic final years because we’ve been blessed with an ability to understand what caused them. We now remember Tom as he was before he began to experience the symptoms of CTE. The son, brother, uncle, friend, and person he was is the memory that will forever live in our hearts.

If you or someone you know is struggling with probable CTE, or lingering concussion symptoms, ask for help through the CLF HelpLine. We support patients and families by providing personalized help to those struggling with the effects of brain injury. Submit your request today and a dedicated member of the Concussion Legacy Foundation team will be happy to assist you.

Bill Jones

Calvin Jones Jr.

Brandon Joyce

Father and son are not only united in death, but are also together forever as Legacy Donors.

Terry’s and Brandon’s passion for football was endless; so much so that both men decided to become donors to help promote medical and scientific research for brain related injuries. Their decision to be part of the same team for concussion advocacy, awareness, education, understanding, diagnosis, and injury management will hopefully help protect players of all ages and make the game they loved that much safer.

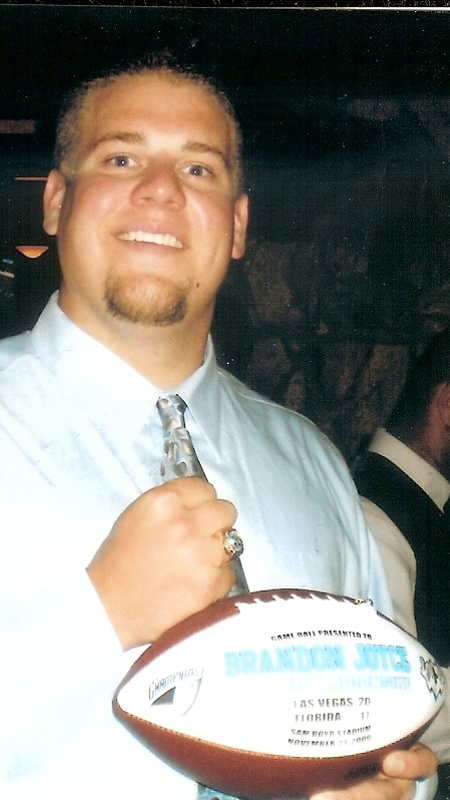

Brandon was the first Concussion Legacy Foundation donated brain of a professional and former NFL football player to be diagnosed “without” evidence of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) by the research team at the Boston University CTE Center. I distinctly remember watching Bob Costas’s Super Bowl XLVI special in 2012 and listening to the discussion about the issues relating to safety on the football field. Bob Costas had several guest, including Concussion Legacy Foundation Co- Founder and Executive Director Christopher Nowinski, who reported that of the 19 former NFL brains that had been donated, 18 were diagnosed with CTE. Only a year later at Super Bowl 2013, it was widely discussed by several media organizations and NFL players about football’s concussion crisis where 34 out of the now 35 donated NFL brains were diagnosed with CTE. That one NFL donated brain “without” CTE was my son’s, Brandon Patrick Joyce, age 26. One of the other 35 NFL donated brains studied “with” CTE, was Brandon’s father, Terrance Patrick Joyce, age 56. Terry was diagnosed by neuropathologist Dr. Ann C. McKee with CTE.

Brandon was the victim of an unspeakable crime: murder. On December 24, 2010, four cousins, all with extensive criminal histories, shot Brandon in the head during a confessed, planned robbery. Four days later, Brandon succumbed to his injuries and passed away on December 28, 2010, at the age of 26. We were then forced to endure not only the indescribable grief of losing Brandon but also a crash course on criminal proceeding. My daughter, Dr. Lindsay Joyce, and I have had to go through an unimaginable, excruciatingly painful legal process of the prosecution of all four of my son’s murderers, all of which have since plead guilty and are currently serving 20 to 45 years in prison.

In life, Terry, my husband and former NFL football player, and Brandon were alike in many ways; so much so that Brandon described the closeness of their relationship as if they were literally one and the same. Upon learning that his father’s brain cancer had returned and after witnessing his dad’s debilitating depression, Brandon texted me, “Mom you are the best mother ever but I love my dad and I feel like him and I am him. Get him that anti-depressant; help him now because he is stronger than that.”

Both Terry and Brandon experienced the dream of becoming NFL football players. Terry was a former St. Louis Cardinal, Los Angeles Ram, San Francisco 49er and Detroit Lion. He played both Punter and Tight End. Brandon was an Offensive Tackle for the United Football League (UFL) Toronto Argonauts and had been on his hometown team the St. Louis Rams roster the year he was killed. Both were Rams, Terry in 1978 and Brandon in 2010. They were big, smart, massive, strong, vibrant, and funny men, both 6’6″ tall weighing over 300 pounds each. Both shared a passion for sports, including: football, basketball, baseball, golf, and were blessed with amazing athletic abilities.

Brandon was quoted April 30, 2010, while at Ram’s Rookie Camp in an interview with Jim Thomas, sportswriter for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, as saying, “I’m 25 years old and I’m out here having the time of my life. I get paid to play a game. And when I go to work, they don’t call it working, they call it playing. I wish I had bigger lips so I could smile bigger. I love this!”

Terry was recuperating at home after brain surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy when Conrad “Big Red” Dobler (a close friend, former NFL teammate, and Pro Bowler) and Jim Hanifan (NFL Head and Offensive Line Coach) came for a visit. Terry, Brandon, and I were all there when Conrad mentioned the study of former NFL players who had donated their brains for the research of CTE. Conrad mentioned that he planned to donate his brain to the study and suggested Terry should do the same.

After Brandon died, it was an understandably very confusing, devastating, and emotionally- debilitating time for our family. It wasn’t until February of 2011 when we learned from the Medical Examiner that they had Brandon’s “brain specimen” to release. We were stunned to learn that they had retrieved and saved Brandon’s entire brain. I asked Lindsay to call and ask Conrad Dobler about which organization he was speaking about that day when he was discussing the study of NFL brains. Conrad then contacted Christopher Nowinski on our behalf. Soon thereafter, Christopher Nowinski spoke with my daughter and discussed the details of the Concussion Legacy Foundation and BU CTE Center Brain Donation Registry. It was that week when we decided to not only donate Brandon’s brain to the BU CTE Center, but also Terry decided to donate his brain as well.

An excerpt quoted from Dr. Lindsay Joyce’s Victim Impact Statement at the sentencing of one of Brandon’s murderers:

“Brandon was an amazing son, brother, boyfriend, cousin, nephew and friend. He was a big man with an even bigger heart. He loved his family! When our dad was diagnosed with brain cancer, he was devastated but remained motivated to help him during the long road ahead. From waiting for him outside the ICU as he came out of the first of two brain surgeries, to encouraging him to get out of bed when he didn’t have the energy, to checking on him during chemo and radiation treatments, to bringing him broccoli cheddar soup because ‘it has anti-oxidants in it.’ Brandon was always motivating my dad ‘to keep fighting and never give up.’ Brandon, however, never accepted our dad’s mortality.

Brandon wasn’t just funny; he was comical. He was quick-witted and sharp, always able to come up with a one-liner on a whim. I never laughed as much, or as hard as I did when I was with him. I miss laughing with my brother.

Brandon was a very motivated, well-liked, successful, and undeniably gifted athlete. My brother was a charitable, generous, and caring person, always willing to help others. Nothing speaks to that more than his donation to the BU CTE Center for the study of CTE. Brandon had signed the back of his license to be an organ donor. Unfortunately, the medications he received in attempts to save his brain, in turn, sacrificed his organs. He was no longer a candidate for organ donation. It wasn’t until we received a call from Boston University that we knew some good could still come out of this horrific event. Brandon’s brain was sent to Boston University to be studied and analyzed as part of an ongoing research project. The goal of the research is to “identify the neuropathology, pathogenesis, and disease course of progressive dementia seen in some athletes as a result of not only concussions but also repetitive forces on the head.” Brandon’s donation will live on forever.” – Dr. Lindsay Joyce

An excerpt from my victim impact statement about Terry’s recorded video:

“On March 21, 2011, Brandon’s girlfriend Rachel and my daughter Lindsay traveled to Las Vegas, Nevada to accept Brandon’s second UFL Championship ring from Coach Jim Fassel of the Las Vegas Locomotives. As I listened over the phone to hear Lindsay accept Brandon’s second UFL Championship ring on his behalf, I laid on my bathroom floor, holding my dog, sobbing hysterically in attempts to keep my paralyzed, grief-stricken, bedridden husband from hearing me cry. I lay there remembering how proud Brandon was after his first UFL Championship and the text he had sent to his dad:

“Today was the greatest day of my life. Because I know I made you proud. You knew I could always do it and that’s the “you” in me, always keep fighting and never give up. Because all I want out of life is to be as good as you. I love you dad. You’re the best.” – Brandon Patrick Joyce

In March of 2011, two days after all four murderers were indicted, we recorded Terry speaking about our wonderful son. We did this knowing Terry would most likely not live to give his Victim Impact Statement in person. I am so thankful he was still able to make his voice heard at the sentencing hearings. In his videotaped statement, you see a broken, frail, weak man with little resemblance to the strong, confident, former football pro, and leader Terry had always been. In his recorded statement Terry says, “I just can’t believe someone would try to do this to our family. We have never done anything to hurt anybody or inflicted pain on anybody.”

When asked how he wanted our son to be remembered; what was Brandon’s legacy? It wasn’t about Brandon’s perseverance, motivation, determination or even his great athleticism. Instead, Terry said he wanted Brandon’s legacy to be that “he was a good guy, a really good guy.”

Brandon was born on September 5th, 1984. Brandon had a real drive, passion, and love for all sports. He began playing T-ball and soccer at age four; tennis, basketball, baseball, and golf would follow later. Terry had worked for Rawlings Sporting Goods in 1980 and had always believed in providing the best equipment for our children. Brandon was big for his age and would beg us to let him to play football. Terry believed speed and agility were the most important factors to a developing, fast-growing, young athlete and encouraged Brandon to stay with soccer, baseball, and basketball. Brandon would not start junior football until the summer of 1996, just before his 12th birthday.

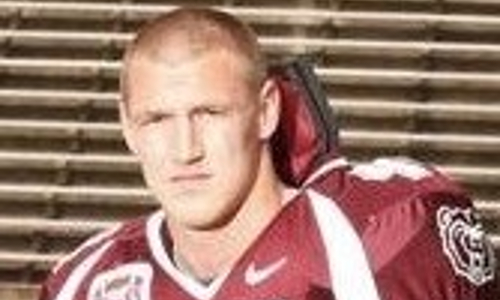

Brandon loved playing football and excelled as quarterback, defensive end, kicker, and special teams, only leaving the field when his team punted. And when his true size and strengths became apparent, he would later play offensive guard, offensive tackle, and defensive tackle for his high school football team.

During Brandon’s senior year at Duchesne High School, Class of 2003, he was selected to the Missouri All-State First Team as an Offensive Lineman. The Missouri State High School Activities Association of Coaches and the Sportswriters recognized Brandon as well. The St. Louis Post Dispatch selected Brandon to their “All-Metro First Team Offense” stating that he was one of the most “dominating players” in the Gateway Athletic Conference. Brandon was captain of Duchesne’s football team and also started for their basketball team as center.

In college, Brandon played Offensive Tackle and sometimes Offensive Guard when needed. He went at everything head first, helmet-to–helmet, especially in the red zone and on all short yardage 3rd and 4th downs. He was always a “head banger” fighting for those inches and yards. You could see and hear from the stands the crushing blows of their helmets and pads colliding. After the game, Brandon would describe some big plays, “as seeing stars” or “being messed up after that one!”

Brandon was recognized as an Indiana University Alpha Beta Honoree and named to the Illinois State University’s “All-Newcomer Team.” After graduating with his Bachelor’s Degree in Business from Illinois State, Brandon signed with the Toronto Argonauts Canadian Football League on his birthday, September 5th, in 2008.

In 2009, he was drafted to the Las Vegas Locomotive (UFL) team, eventually winning the UFL Championship in their inaugural season.

In April of 2010, Brandon was invited to the Rams Rookie minicamp and signed as a St. Louis Ram in May. Brandon would not make the final roster and returned to the Las Vegas Locomotives in August. Shortly thereafter, Brandon suffered a severe knee injury that required surgery.

Brandon spent the last four months of 2010 in Birmingham, Alabama rehabilitating his knee with some of the top Sports Medicine doctors in the nation. His first week there, Brandon met a young Medical Assistant, preacher’s daughter, and the love of his life, Rachel Hubbard. Birmingham was a very familiar place for our family as Lindsay had played Division 1 volleyball for the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) and had graduated with a Bachelors of Science degree in Biology in 2004. We visited Brandon twice in Birmingham during his recuperation and fell in love with Rachel as well. Not long after, Brandon posted on his Facebook page the comment, “She’s the one!”

Brandon was home for just 24 hours before he was shot. It was during this time that he spoke to me about how he planned on asking Rachel to marry him on New Year’s Eve.

On June 17th, 2011, my loving husband, Terry Joyce, died at the age of 56 at home, surrounded by me and my daughter. A parent should never have to bear witness to their child’s murder; a parent should never have to bury their child; a parent should not have to die without both of their children by their side. Exactly six months to the day of Brandon’s shooting, we buried Terry next to Brandon. Jackie Smith, Hall of Fame Tight End, provided an amazing voice and tribute to both Terry and Brandon by singing “O’ Danny Boy” at both of their memorials.

I have been enthusiastically cheering my whole life. I have a true love and passion for football, as well as many other sports. My husband Terry was inducted to Highland Community College Athletic Hall of Fame as a three-sport athlete and became an All-American football player for the Missouri Southern State University Lions as a punter and tight end. Terry went on to live the dream of playing in the NFL. Our daughter Lindsay played Division 1 college volleyball for UAB. Our son Brandon played college football for Division 1 Indiana and 1A Illinois State and professional football for the CFL, UFL and NFL.

In high school and college, Brandon would get “dinged up,” but would never want to miss a minute, snap, play, or down. His sacrifice was all for the love and excitement of the game. Brandon’s college football teammates, too, would laughingly describe their head injuries as feeling dazed or goofy, getting their bell rung, or having just a bad headache. It are those dangerous cumulative repetitive hits to the head, left mostly undiagnosed, that the Concussion Legacy Foundation and Boston University Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy are bringing critical awareness to and contributing the necessary research in hopes of ensuring the safety of all athletes.

It is our hope that by sharing Brandon’s and Terry’s stories we will bring attention to the inherent dangers of concussions, that the very important research available through the Concussion Legacy Foundation and the BU CTE Center will be shared and create additional awareness about repetitive concussive and sub-concussive brain injuries, and that these discussions will offer an informed dialogue with parents, youths, coaches, athletes of all ages, and the news media to have a better understanding of the scope of the concussion problem. As Legacy Donors, Terrance Patrick Joyce and Brandon Patrick Joyce, father and son, will live on together, both big men, forever on the same team.

Terry Joyce

Father and son are not only united in death but are also together forever as Legacy Donors. Terry’s and Brandon’s passion for football was endless; so much so that both men decided to become donors to help promote medical and scientific research for brain related injuries. Their decision to be part of the same team for concussion advocacy, awareness, education, understanding, diagnosis, and injury management will hopefully help protect players of all ages and make the game they loved that much safer.

My son Brandon was the first Concussion Legacy Foundation donated brain of a professional and former NFL football player to be diagnosed “without” evidence of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) by the research team at the Boston University CTE Center. I distinctly remember watching Bob Costas’s Super Bowl XLVI special in 2012 and listening to the discussion about the issues relating to safety on the football field. Bob Costas had several guests, including Concussion Legacy Foundation Co-Founder and Executive Director Christopher Nowinski, who reported that of the 19 former NFL brains that had been donated, 18 were diagnosed with CTE. Only a year later at Super Bowl 2013, it was widely discussed by several media organizations and NFL players about football’s concussion crisis where 34 out of the now 35 donated NFL brains were diagnosed with CTE. That one NFL donated brain “without” CTE was my son’s, Brandon Patrick Joyce, age 26. One of the other 35 NFL donated brains studied “with” CTE, was Brandon’s father and my husband, Terrance Patrick Joyce, age 56. Terry was diagnosed by neuropathologist Dr. Ann C. McKee with CTE.

Brandon was the victim of an unspeakable crime: murder. On December 24, 2010 four cousins, all with extensive criminal histories, shot Brandon in the head during a confessed, planned robbery. Four days later, Brandon succumbed to his injuries and passed away on December 28, 2010 at the age of 26. We were then forced to endure not only the indescribable grief of losing Brandon but also a crash course on criminal proceedings. My daughter, Dr. Lindsay Joyce, and I had to go through an unimaginable, excruciatingly painful legal process of the prosecution of all four of my son’s murderers, all of which have since plead guilty and are currently serving 20 to 45 years in prison.

In life, Terry and Brandon were alike in many ways; so much so that Brandon described the closeness of their relationship as if they were literally one and the same. Upon learning that his father’s brain cancer had returned and after witnessing his dad’s debilitating depression, Brandon texted me, “Mom you are the best mother ever but I love my dad and I feel like him and I am him. Get him that anti-depressant; help him now because he is stronger than that.” Both Terry and Brandon experienced the dream of becoming NFL football players. Terry was a former St. Louis Cardinal, Los Angeles Ram, San Francisco 49er, and Detroit Lion. He played both Punter and Tight End. Brandon was an Offensive Tackle for the United Football League (UFL) Toronto Argonauts and had been on his hometown team the St. Louis Ram’s roster the year he was killed. Both were Rams, Terry in 1978 and Brandon in 2010. They were big, smart, massive, strong, vibrant, and funny men, both 6’6″ tall weighing over 300 pounds each. Both shared a passion for sports, including: football, basketball, baseball, golf, and were blessed with amazing athletic abilities.

Both Terry and Brandon were marked with the same scar from brain surgery prior to their passing; Terry’s, a result of brain cancer and Brandon’s a result of a gunshot wound to the head at the hands of others (homicide). Both brains, NFL father and son, were donated to the BU CTE Center. On June 17, 2011, my loving husband, Terry Joyce, died at the age of 56 at home, surrounded by me and my daughter. A parent should never have to bear witness to their child’s murder; a parent should never have to bury their child; a parent should not have to die without both of their children by their side. Exactly six months to the day of Brandon’s shooting, we buried Terry next to Brandon. Jackie Smith, Hall of Fame Tight End, provided an amazing voice and tribute to both Terry and Brandon by singing “O’ Danny Boy” at both of their memorials.

Although Terry died in June of 2011, well before the completion of criminal proceedings, he was able to make his voice heard in the sentencing hearings of all four of Brandon’s convicted murderers. In Terry’s videotaped Victim Impact Statement, you see a broken, frail, weak man with little resemblance to the strong, confident, former football pro, and leader he had always been. Terry says, “I just can’t believe someone would try to do this to our family. We have never done anything to hurt anybody or inflicted pain on anybody.” Terry spoke about how Brandon had always helped young athletes at football camps. Upon hearing about one young man who couldn’t afford new shoes, instead using duct tape to hold together an old pair, Brandon gave the young man several pairs of his own football shoes. (We would later donate all of Brandon’s athletic shoes and football equipment to the youth’s high school). When asked how he wanted our son to be remembered; what was Brandon’s legacy? It wasn’t about Brandon’s perseverance, motivation, determination or even his great athleticism; instead, Terry said he wanted Brandon’s legacy to be that, “He was a good guy, a really good guy.”

At the age of 12, Terry won Missouri’s “Punt, Pass & Kick” competition and was awarded a plaque and Cardinal helmet. Terry participated in football, basketball, baseball, golf, and track & field while attending Knox County High School from 1968 to 1972. Terry’s #10 Jersey was retired at a half-time ceremony of the Knox County varsity football home opener on September 9th, 2011. A marquis is planned near the entrance of the Knox County R-1 campus east of Edina in memory of Terry, the only NFL player to date in school history.

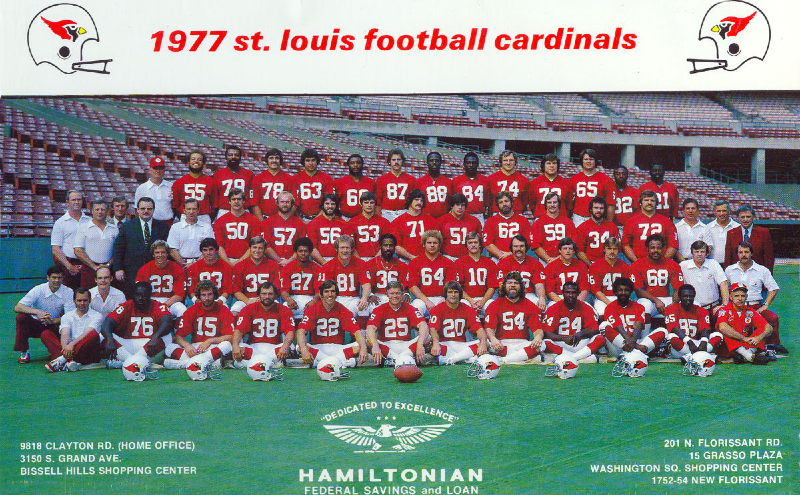

Terry was so gifted athletically that he was not only offered contracts to play professional football but also professional baseball. As a senior at Knox County High School, Terry was scouted and offered a baseball contract by the Cincinnati Reds. He, however, chose college football and went on to play at Highland Community College in Kansas. Terry was inducted to Highland Community College Athletic Hall of Fame as a three-sport letterman. As a member of the Scottie Football Team, he played quarterback, tight end, and punter. On the basketball court, Terry played forward and center, and on the baseball field, he was the team’s pitcher, along with seeing action at first and third base. After he left Highland Community College, Terry attended Missouri Southern State University, where he was recognized as an All-American Tight End and Punter. During his senior year, Terry led the nation in punting average and was eventually signed by the St. Louis Football Cardinals.

Terry and I met in Kirksville, Missouri, in May of 1976. I was 21-years-old entering my senior year at Northeast Missouri State-Truman. Terry was 21-years-old, too, and lived in the nearby small town of Edina, Missouri, total population of 1400. He was at home working-out nonstop getting ready for football camp starting in July in St. Louis. I had plans to go back to St. Louis, where I was born and raised, to begin student teaching in Elementary and Special Education. It was the perfect match! Together, we had so many things in common, including a passion for sports. I had been a loyal St. Louis Cardinal fan my whole life; my dad was a season ticket holder and former high school football coach and assistant basketball coach. I have been enthusiastically cheering for sports teams my whole life, having a true love for football along with a great passion for many other sports.

Terry and I were inseparable from the moment we met. Together, we headed to St. Louis in July. We were married May 27, 1978. Terry would go on to live the dream of playing in the NFL. Terry was coached by future Hall of Famer Don Coryell and played with NFL Hall of Famers, Tight End Jackie Smith, Offensive Lineman Dan Dierdorf, and Defensive Back Roger Wehrli on the St. Louis Football Cardinal’s team in 1976 & 77.

Terry and I had two children, Lindsay Ann Joyce born April 4, 1982 and Brandon Patrick Joyce born September 5, 1984. Our children, taking after their athletically-gifted father, both became Division-I scholarship collegiate athletes, our daughter Lindsay played Division 1 volleyball for the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) and our son Brandon played Division 1 college football for Indiana and 1A Illinois State. After graduating from UAB with her Bachelors of Science in Biology, Lindsay went to medical school at the University of Missouri-Columbia. Upon earning her Doctorate in Medicine, M.D., Lindsay went on to complete her residency training in Emergency Medicine at the University of Louisville Hospital, Level I Trauma Center, and is currently an Attending Physician in Emergency Medicine. After College, Brandon enjoyed a career in professional football with the CFL, UFL and NFL.

Terry had many, many best friends, and people who truly loved him. From his friends he was also given a lot of nicknames; “The Big Man”, “The Man” “#87″, “Big Foot”, “Daddy T”, “TJ”, “Friendly Terry” and “Big Buddy” to quote a few.

Ron Meyers had these words to say about Terry’s friendship and mentoring his son, Will Meyer #39 IU, first team freshman All-American & Big Ten Defensive Freshman of the Year honors, roommate and friend to Brandon:

“For Will, Terry was kind of a second father and role model/mentor during an important time of his life. Terry’s constant encouragement for the “headhunter” was something that kept feeding his desire to perform at the highest level he was capable of. For me, Terry was simply my best friend. The best thing I can say about him is that he acted like everyone’s best friend – from the parking attendant at IU, to the ticket lady, to the restaurant manager (JB), to the trainer. He had that kind of charisma and interest in the people around him. He was not too good for anyone. And he saw the best in everyone he met. I will never forget ‘The Man’ or your entire family.”

Edina native, Knox County Sports writer, David Sharp wrote in the Edina Sentinel on June 29, 2011 (excerpt):

“Terry was hired by the Rawlings Sporting Goods Company of St. Louis. He later joined a St. Louis area Miller brewing company distributor as a salesman. Later became The General Manager for Best Beers. Terry Joyce moved on to one of the largest adult beverage distributors in the Midwest. Joyce had an 18-year career with Major Brands, one of the top Missouri businesses in terms of sales and coverage area. After rising to the top of the football world, Terry Joyce ascended to the upper levels of the St. Louis area business community. He eventually became the General Sales Manager and Vice President of Sales for Major Brands Premium Beverage Distributors in St. Louis.”

NFL Alumni spokesperson Jim Morris offered this comment to the Edina Sentinel from his New Jersey office:

“The NFL Alumni wants to tell the Joyce family that the thoughts and prayers of the entire NFL Alumni organization are with them as they go through this time. Terry Joyce had a tremendous impact on the football community…. He (Terry) sat on the St. Louis NFL Alumni Board of Directors. He touched many lives with his work with the NFL Alumni, and also during his bought with cancer.”

The Edina Sentinel continued to say: Terry Joyce played in numerous charitable golf tournaments for Missouri Southern State, the NFL Alumni and many others. Joyce was a championship flight golfer until the final years of his life. Conrad Dobler, also known as ‘Big Red’, was one of the most feared guards in the NFL during his ten year playing career. Dobler was a Pro Bowler in 1975, 76 and 77. Conrad Dobler currently works for the NFL Alumni in their Kansas City office. According to NFL Alumni spokesman Jim Morris, the St. Louis NFL Alumni chapter has disbanded.

Conrad Dobler offered the following comments to the Edina Sentinel of his St. Louis Cardinal teammate:

“I had the opportunity to play with Terry Joyce for two years. He was one of the biggest punters ever in the NFL. He could really boot the ball. He was a really good guy. If you needed anything, Terry was there to help you… Terry certainly gave back to the community he lived in. That’s what made him special. He was bigger than life!”

Conrad continued…

“Terry could have probably had a nice career as a tight end and a punter. We had a pretty good tight end in Hall of Famer Jackie Smith and JV Cain. More yards are exchanged in the punting game than any other facet of the football game. Terry covered more yards than anyone else. He had more yards than (running backs) Terry Metcalf and Jim Otis put together. Most kickers and punters are kind of strange guys. That wasn’t Terry. He was right in the middle of it all in practice. He ran the opposing defenses for us in practice. Outside of football, he always made sure I had engagements to do when he worked for the Miller Distributor.”

Conrad Dobler had national endorsements for Miller Beer. Dobler was one of the ‘Miller All-Stars’ of his era. He said of Terry, “He took care of his own. He helped raise a lot of money for charity. Terry got involved. If you knew Terry, you couldn’t-not like the guy.”

Clarence Cannon, an All-Conference basketball player at Knox County, offered the following comment on playing with Terry Joyce at Knox County:

“Terry was the finest teammate anyone could ask for in sports. He had a great sense of humor and quick wit. When he walked onto the baseball diamond, the football field or the basketball court he became the most intense and focused person I ever knew. I don’t think there is any question he was the best all-around athlete Knox County High School ever saw.”

Another former teammate at Knox County and current Marceline High School teacher, Brian McGlothlin, remembered Terry by saying:

“What many people do not realize is the level of fierce competitiveness he possessed. As his teammate, I was often caught up in the middle of the game just watching him perform. He was one of my sports heroes growing up.”

Milan head football coach and Knox County R-I graduate John Dabney said:

“I remember sitting in a third grade classroom at St. Joe and feeling the thrill when I heard Terry Joyce had made the St. Louis Cardinals football team. I looked through a lot of Topps Football Cards before I got Terry’s card. I still have the card today. I don’t think Terry really got the recognition he deserved in Knox County. He was a great athlete, no doubt the best athlete ever at Knox County.”

Terry had at least two known concussions. One occurred while playing quarterback for the Highland Scotties. Terry was ‘knocked out’ on a pass play and ended up face down in a muddy puddle. The coaches and players ran onto the field to roll Terry’s mud-caked body over so he could breathe. Dale Miller, a lifelong friend and teammate, remembers helping Terry off the field. Terry would later jokingly describe the story of how he woke up in a fog on the bench not knowing what had happened, where he was, or how much time had passed. This was the typical story of concussions back in the day; players were told to ‘shake it off’ and get right back into the game.

It is our hope that by sharing Terry’s and Brandon’s stories we will bring attention to the inherent dangers of concussions, that the very important research available through the Concussion Legacy Foundation and the BU CTE Center will be shared and create additional awareness about repetitive concussive and sub-concussive brain injuries, and that these discussions will offer an informed dialogue with parents, youths, coaches, athletes of all ages, and the news media to have a better understanding of the scope of the concussion problem. As Legacy Donors, Terrance Patrick Joyce and Brandon Patrick Joyce, father and son, will live on together, both big men, forever on the same team.

Dylan Karczewski

Michael Keck

Doctors couldn’t find what was wrong with Michael Keck, but football star knew it would kill him

—

The Kansas City Star

Her head lay on her husband’s chest and she listened to his heart beat for the last time. He took his final breaths, his body pressing against her cheek. She held his hands, still warm, in a room full of doctors and nurses and the love of her life.

In the seconds after he slipped away, her first thought was of the way Michael Keck looked at their son. Such complete joy, like nothing else in the world mattered. She’d never seen anything like it. Still hasn’t.

Michael was 25 years old. Should’ve had a full life in front of him. A former football star at Harrisonville High and later Missouri and Missouri State, with so much going for him.

He was smart, with an unrelenting energy. Kind and impossible not to like, except when the demons came. Justin, their son, was not yet 3 when Michael died in 2013, too young to remember anything about his dad. That’s one reason Cassandra wants to tell this story.

She walked her husband’s body to the morgue that day. They wanted to put him on a cold, plain, metal table. That seemed horrible to her. They kept him on the bed instead, and her father helped her clean Michael’s body. There was so much blood. His head was swollen, puffy, like a bag of water rested underneath his skin.

They had pushed on his chest for an hour, then two hours, then three, trying to bring him back to life. The trauma broke a blood vessel on his neck. Clamps held his eyes open. It was a gruesome end to what should’ve been such a long and beautiful life.

Michael and Cassandra were made for each other, sharing an inseparable bond even through the storm, and she was not ready for it to end. Football took Michael away at a startlingly young age, and that’s the other reason Cassandra wants to tell this story.

She tries not to cry.

“He was everything I wanted,” she said. “I was everything he wanted. Physically, mentally. It was like our souls were alike.”

At the crematorium, there was a tiny window. Cassandra watched his casket push into the flames. She saw it catch on fire. This was her way of saying goodbye to his body.

To the very end, she was by his side.

Michael Keck was a survivor. That’s what makes his death so hard to take even now, two years later, for those who loved him and knew him and looked up to him.

He grew up in Harrisonville, a town of fewer than 10,000 people 40 miles south of downtown Kansas City on U.S. Highway 71. His parents, both of them, became addicted to drugs when he was young. Neither returned messages for this story, but Charlotte Keck — Michael’s grandmother — remembers both doing meth with the kids in the house. Once, they burned a hole through a table and the floor underneath. Charlotte took full custody of Michael when he was in sixth grade.

Michael grew up big and strong, with a warmth and perspective that transcended his parents’ struggles. When he was just a boy, and found out his mom had been arrested again, he told Charlotte: “I hope she gets the help she needs.” Later, in high school, he was asked if he ever got angry that his parents weren’t around more.

“No,” he said. “Because that’s part of what made me who I am, and I like who I am.”

Michael was different. Growing up, he was a terrible basketball player — “the worst you ever saw,” one of his friends jokes now — but he made himself a starter on his high school team through force and determination and hours at the local park, where he studied the tendencies of all the regulars. He had asthma but refused to use an inhaler, simply running until it no longer hurt.

He was surrounded by love, even when his parents weren’t around. There was Charlotte, and Bill Collins, a judge in Harrisonville whose sons became Michael’s best friends. Michael had his own room at the Collins’ house. Michael loved them back. He made movies with his friends, broke into the school with them to lift weights, and during football season made it a point to watch as much film as possible so he could tell his teammates how to attack their next opponent. At the funeral, Charlotte remembers hearing story after story about Michael sticking up for someone.

Michael was a football prodigy. He started at Harrisonville High as a freshman, and the coach soon learned that Michael gave his best at practice when another freshman was called up to varsity to work with him. Always, it was about his friends.

Around Harrisonville, they told the story of Michael’s first game, when he tackled a kid so hard that pieces of his helmet flew off. Set to a song that goes, “Here comes the BOOM,” video of that play is worn down now, they watched it so often. Later, that play would take on a darker tone.

Keck was one of the brightest high school football recruits in the class of 2007. A defensive end, he sacked Cam Newton, now the star quarterback of the Carolina Panthers, in an all-star game. Alabama, Michigan, and Southern California offered scholarships. He told his grandma he wished he could divide those offers amongst his friends.

He signed with Missouri, and might’ve chosen an even smaller program if not for expectations in his hometown.

“He had the burden of carrying the hopes and dreams of a lot of Harrisonville people,” Collins said.

“He knew if he went to a smaller school, a lot of people would’ve been let down because they expected to see him on TV,” said Steven Collins, Bill’s son and Michael’s best friend. “He wasn’t cut out for (Division I football). For him, it ruined what football was about.”

Tears flowed down Michael’s cheeks as he knocked on the door of his high school football coach. This was spring of his ninth-grade year, and Michael didn’t try to hide his hurt. His girlfriend had broken up with him, and in that moment that’s all that mattered.

Fred Bouchard sat mostly in silence, comforting Michael where he could. Bouchard has coached for 30 years. He’ll never forget that conversation.

“His heart was broken,” Bouchard said. “I’ve done this a while, and there’s only five guys who’d be willing to have that conversation with their coach, and he’s the biggest bad-ass football player we ever had.”

That juxtaposition — the best athlete in the school, a smart, good-looking boy completely vulnerable — was Michael. He knew pain. At lunch, he scanned the cafeteria for someone sitting alone. That’s the person Michael wanted to talk to, to ask questions of, to listen to, to maybe brighten their day. In college, he befriended a student with severe facial burn marks. Others recoiled at the sight. Michael invited him over to play video games.

“He wasn’t a saint,” said Steven Collins, Michael’s best friend. “But he was pretty close.”

Michael didn’t like football. Not at first, anyway. In grade school, long before anyone knew what kind of talent Michael had, he made excuses as to why he couldn’t play in almost every game. His ankle. His hamstring. His arm.

He cried in the middle of most games, and he said it was because something hurt. But Steven — who played with Michael through high school — came to think Michael was upset at not making a play. He hated letting down his friends.

Eventually, football became central to Michael’s life. He was the best player on the field, always, but that’s not what he liked most about it. He enjoyed competing, and that he had something to do with his friends.

In high school, his size and athleticism caught the eye of an area AAU basketball coach. But Michael didn’t want to play without his friends, so they formed their own team. Bill Collins coached it. They bought plain white T-shirts, scribbled their numbers with a Sharpie, and called themselves the Running Rebels. The first tournament they entered, Michael dominated a kid who would later earn a Division I basketball scholarship.

Stories about Michael and sports always tended to go this way. He was drawn in because he wanted to be with his friends, then wound up being the star, which was a little awkward because that was never the point.

“That’s exactly right,” Steven said. “He was really uncomfortable with the limelight. He just loved being out with his friends.”

Michael was good enough at football that some thought he could make a career of it. Coming out of high school, he was a higher-ranked recruit than scores of guys who are now millionaires. Those were always someone else’s dreams, though. Someone else’s expectations.

Charlotte remembers asking her grandkids what they would do if they won the lottery. Michael said he would move to Hawaii, find a cottage, and buy a soda fountain.

On the surface, Mizzou looked like a terrific fit for Michael — one of the nation’s top pass-rushing prospects at one of the nation’s top schools for pass rushers.

Looking back, knowing what we know now, some from Harrisonville wonder if Michael’s brain was damaged before he even left town.

Cassandra first saw Michael in an elevator. She will never forget that moment they made eye contact, and the power they both felt. They stood there, silent, staring at each other. Cassandra could not look away.

Michael was shy, and later had a friend ask for Cassandra’s number. They hung out the next day, the two of them and Steven, with whom Michael lived after transferring from MU to Missouri State. They watched a movie. Something on Netflix; Cassandra doesn’t remember the show. What she does remember is Michael sitting on the other side of the room, and then, after a while — finally — asking if he could come sit next to her.

“We never stopped hanging out after that,” Cassandra said. “It was kind of like an addiction.”

One of Michael’s friends wonders if the first sign of trouble was Michael leaving Mizzou. He redshirted in 2007, and played one game in 2008, the whole time telling people back home that big-time football wasn’t for him. It wasn’t the decision that was surprising, but the way he left Columbia.

He just walked away. Quit. Michael never quit anything. But after a group text message to his coaches, he was gone.

“That’s not Mike,” said Zack Livingston, a friend from Harrisonville. “He regretted that. He wished he would’ve done it differently.”

As he moved on from Mizzou, Michael and Cassandra fell for each other, hard. He liked her passion, and her creativity, and her intelligence. She liked his gentleness, his work ethic and the natural way he accepted people without judgment. It was the last new relationship Michael would ever make.

He and Cassandra isolated themselves. In the beginning, it was purely choice. Love, obsession and choice. They did everything together because it felt good, it felt right, it was all they wanted. Then, slowly, rules started to change. Cassandra rearranged her life for Michael.

“I got rid of everybody,” she said, “to get his full trust.”

Michael began to forget things. His keys. His wallet. His words. Cassandra would try to complete his sentences, and Michael would get mad because it wasn’t what he was trying to say. That happened a lot. Sometimes, the anger was worse than others.

“He’d get, like, somebody else for a couple minutes,” she said. “I wouldn’t hold it against him. ‘What can we do to keep that from happening again? Let’s work as a team.’”

Cassandra’s life became largely about not upsetting Michael. If she was going to be five minutes late, she called. She broke off contact with her friends, even with her parents, because that avoided problems with him. She hung blankets over the windows, because the outside light made his head hurt. She kept their place as clean and as organized as possible, Michael’s keys and hat and coat in exactly the same place, so he would know where to find them. Anything that might start an argument, Cassandra wanted to fix before it became a problem.

They did everything together. If Michael mowed the lawn, Cassandra picked up leaves and sticks. If Cassandra washed the dishes, Michael dried them. Michael even wanted her in the room when he played video games. Once, she was in their bedroom watching TV and Michael got so mad he stormed in and slammed the set to the ground. She got used to the outbursts.

He threw a video-game controller at her, the plastic device zooming into her back and leaving a deep bruise. Sometimes, the violence was more personal. She learned how to defend herself, how to use her arms to protect her head, and that crying only made it worse.

“I would have to sit there,” she said. “Until the pain went away.”

It used to be they were alone because that’s what they wanted. More and more, it was because Michael didn’t want anyone else to see what he had become. He always apologized. He always felt bad. He knew that this wasn’t him, and Cassandra believed him.

Michael tried to work but couldn’t hold a job. He got tired quickly, and too much action made his head hurt. There was a vein on the right side of his forehead, visible his whole life, but when the pain was really bad Cassandra saw it pulsate.

The last two years were the worst. Michael had always been a bit compulsive about his hygiene, but now he’d go days without showering. He would forget to eat. He began to talk about death. He told people he was an old man in a young person’s body, and once asked his grandma why her brain worked better than his.

The violence worsened, too. Cassandra had an emergency plan. She moved the dresser in a way that she could shut the door and stiffen her legs against the furniture to keep him out. She didn’t always get there in time, so she learned to protect herself. Arms up.

“I never took it personal,” she said. “I saw everything. I was with him every day. He showed me every part of his suffering. I saw it all.”

About two months before Michael died, he and his wife talked about the first time they met. They had never done that before. Not after they started dating, not at their wedding, not even the night after they married, when they sat in that cabin with Steven and laughed all night at old stories.

They had been through so much. The love. The fights. The laughs. The tears. Justin. Toward the end, they moved to Colorado together, because maybe they just needed a change of scenery.

After all of it, Cassandra could still feel what she felt in the elevator that day. Such intensity.

She asked Michael if he remembered. He said he did. She asked what he was thinking.

“You were the most beautiful woman I ever saw,” he said.

Michael’s life became an impossible puzzle he tried to solve by himself. Doctors couldn’t help. Test results didn’t show anything. So he pulled all-nighters on the computer. He stayed up until three, four, five o’clock in the morning, drawn to the stories and videos about brain trauma and concussions.

When former NFL star Junior Seau shot himself, Michael watched the news and realized that so much of what he heard sounded like his own life. A good man prone to violent outbursts and memory loss. He saw how those stories always ended.

Michael knew death was coming. Some days, he wanted to die. Maybe then people would understand. Maybe then they would know he wasn’t making this up, or whining, or taking the same sad fall his parents had. He wanted people to know this was real.

Michael had one final wish, which he made Cassandra promise to fulfill. He wanted his brain donated for study. Something had to be wrong. The headaches. The inability to concentrate. He used to be so friendly, so thoughtful, particularly to people who needed a smile. Then, he wanted nothing to do with anyone.

Michael knew the men whose brains had betrayed them were in their 50s, their 60s, their 70s. Most had enjoyed long careers in the NFL. But he was feeling the same things they talked about. It sounded crazy, and Michael knew it.

He was in his 20s. A kid. He was once a force of nature, a package of size and strength and speed that made anything seem possible. But he played only one game at Missouri and one season at Missouri State. He remembered two hits worse than most, and figured he had undiagnosed concussions from high school, but there was no extensive history of documented injuries. How could he think his suffering was the same as those old men?

But the way he felt, how could he think anything else?

Cassandra loved Michael completely, but she was powerless through much of their relationship. Powerless to calm Michael’s rages, powerless to make him feel better in the quieter times.

Some wondered if Michael was mixed up in drugs, like his parents. Cassandra knew better than that, but she didn’t have any answers. She believed Michael, that something was wrong with his head, but without a diagnosis it was hard to be sure. Doctors never could find anything wrong. And after a while, Michael stopped going in for tests.

Then, a few months after he died on Oct. 21, 2013, the researchers called.

They had studied hundreds of brains, and never saw one like Michael Keck’s.

Chronic traumatic encephalopathy, commonly known as CTE, is a progressive degenerative brain disease found in athletes and soldiers and others with a history of repeated brain trauma.

The disease has taken on a greater profile in recent years as advanced forms of CTE have been found in retired pro football players. Many of them died at an early age, their final years marked by memory loss, confusion, violence, depression and, in some cases, suicide. Their symptoms often mirror dementia, though CTE can only be diagnosed after death.

CTE had been found almost solely in older players. Retired players. Seau is perhaps CTE’s highest-profile victim. He was 43, with a 20-year NFL career, when he killed himself with a gunshot to the chest.

Michael was 25. Researchers had never seen such an advanced case of CTE in a brain so young. His story has become one of the most powerful parts of presentations on the disease.

“I have to say, I was blown away,” said Ann McKee, a neuropathologist at Boston University who studied Michael’s brain. “This case still stands out to me personally. It’s a reason we do this work. A young man, in the prime of his life, newly married, had everything to look forward to. Yet, this disease is destroying his brain.”

There is no way of knowing for sure, and there is reason to believe the biggest danger is when smaller hits stack up, but Michael Keck thought the worst hit he ever took was at Missouri State.

His helmet had been malfunctioning, the pads inside losing air. Before he could fix it, he took a massive blow to the side of his head. Research shows this might be the worst way to be hit. Michael lost consciousness, and in all the years he’d played football, that never happened before.

“That was the hit he would talk about,” Cassandra said.

Michael quit football shortly after that collision, which happened around the time they found out Cassandra was pregnant. He was already having problems with his mind by then, and he wanted to be around for his son. That was in 2010. In two years, Michael had gone from a bright future at one of the nation’s top programs to quitting the sport.

“We both had tears in my office,” said Terry Allen, Keck’s coach at Missouri State. “He was a great kid. Loved to play. I loved that kid. That’s a hard deal.”

Michael walked away from the game about three years before he died. Cassandra said she is not interested in lawsuits. She wants answers, and for Michael’s suffering to push forward the understanding of CTE and potential dangers of football.

The rate of Michael’s descent, his relatively short-term exposure to the sport, and his heartbreakingly young age make his a potentially ground-breaking case for scientists and physicians studying the disease.

“It reinforces the notion that some people are very susceptible to this disease,” said McKee, the neuropathologist. “They are exposed to this in amateur sports. They don’t have to be professional athletes bashing their heads in for a living.

“Michael, for whatever reason — and we need to figure it out — was very susceptible to this. This is just not acceptable. Whatever rate this is happening in our college and high school athletes, even if it’s low, it’s an unacceptable level.”

Michael’s official cause of death was a staph infection, which caused fatal heart problems, but CTE made this tragedy inevitable. Michael’s condition was only getting worse, and his suffering deeper. A good analogy is Alzheimer’s, which doesn’t technically kill a person but makes them waste away and die from other complications, such as pneumonia.

Michael’s case brings up so many questions. So many fears. It proves that professional players — adults who make conscious decisions to play, and are well-compensated — aren’t the only ones at risk. Perhaps researchers can learn something specific about Michael’s brain, or his exposure, that caused the disease to spread so rapidly.

Maybe Michael’s suffering — and the pain it caused Cassandra and others — can lead to new knowledge that might help someone else.

“I need to do this for Michael,” Cassandra said. “He wanted so badly for people to know about this. He did so much research on it. It can’t stop there.”

The first thing you see when you walk into Cassandra Keck’s house is a picture of Justin, smiling as wide and bright as a little boy is capable of smiling. If you knew Michael at all, the resemblance is stunning.

It’s not just the face, either. Cassandra remembers Michael and Justin standing in the bathroom, both without shirts, waiting for the water to warm up for a bath. The head shape. Their hair. The way their necks became shoulders. It was identical. Even now, she laughs when she tells the story.

Justin and Michael had their own language. Mmmmm, was hungry. A cough meant Justin was thirsty. He cried in his crib, and Michael knew that meant he wanted to sleep with a toy. Those are Cassandra’s memories, and they are good memories. They are great memories. This, too, is part of what she wants to pass along.

“Justin will tell kids at school, ‘My dad died,’ ” Cassandra said. “He’ll say, ‘He got sick.’”

She thinks all the time about what she wants Justin to know about his father. At the funeral, she gave everyone pens and paper and asked them to write down their memories of Michael. She’s saving everything, and when he’s ready, Cassandra will share it all with Justin.

She wants him to know his dad was loyal, and that he was always there for people, no matter what, even if they’d done something to hurt him before. She wants Justin to know his dad worked hard, freakishly hard, to make what he wanted a reality. She wants Justin to know his dad never complained, even when he had plenty of reason to. More than anything else, she wants Justin to know how much his dad cared, and wanted a better life for his son, one without the uncertainty and ups and downs he went through.

On the wall at Charlotte’s house is a picture of the 2006 Harrisonville High football team. That team was loaded, going undefeated and winning the state championship game by five touchdowns. Their best player was Michael, who borrowed a suit and tie for the team picture and sat at the end of a row. That season was the last time he was happy on the football field, the last time he was able to play with his friends.

Every now and then, Justin points at the picture.

“Dad,” he says. “Dad dead.”

Then he points higher.

“Yeah. He’s up there now.”