In the postgame frenzy of the 1960 NFL Championship at Franklin Field in Philadelphia, Gerald “Gerry” Huth found his old coach, Vince Lombardi.

“Hey coach!” Huth joked to the notoriously dour Lombardi. “Thanks for teaching me how to block!”

Minutes earlier, Huth’s block sprung Philadelphia Eagles’ fullback Ted Dean open for the game-winning touchdown against Lombardi’s Green Bay Packers. Five years earlier, Lombardi was Huth’s offensive coordinator for the NFL Champion New York Giants.

The defender wearing 47 in white whom Huth displaced on the play was Jesse Whittenton, a star defensive back for the Packers. 60 years later, Huth and Whittenton are connected in another way. Both of their brains have been diagnosed with CTE by researchers at the UNITE Brain Bank.

Humble beginnings

Gerald Huth was born in July 1933 in the small town of Floyds Knobs, Indiana, six miles outside of Louisville. He was the second oldest of seven children in a devout Catholic family. Huth always aspired to ascend out of his circumstances.

Tragedy struck when Gerald’s father passed when Gerald was just 16 years old. He was quickly thrust into the provider role, a role he would take on for the rest of his life.

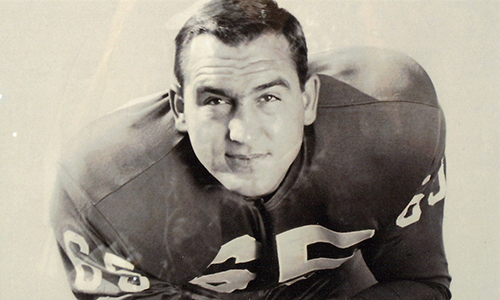

Huth turned out for the New Albany High School football team and played well enough to earn a scholarship at Wake Forest University in 1952. In three consecutive seasons, Huth earned a spot on the Carolina College’s All-Star team in 1952, was named 2nd Team All-ACC in 1953, and Honorable Mention All-ACC in 1954.

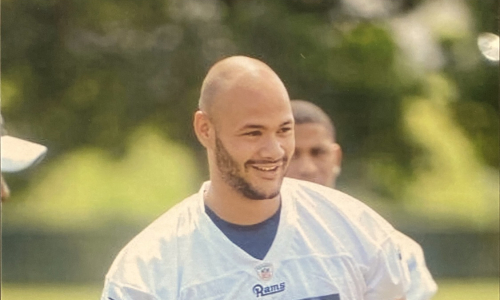

The New York Giants selected Huth with the 285th overall selection in the 1956 NFL Draft. Football had taken Huth from a county of less than 45,000 people to a city of nearly eight million.

“He tried to help everybody.”

Diane Huth was on vacation from Pittsburgh to South Florida. She missed her flight home and lost her job. Her search for a new job led to a position with an airline. She accepted without quite reading all the fine print. The job required relocation to New York City.

She stayed with a college roommate and while at a friend’s house, Gerald Huth walked in with a case of Ballantine beer. Diane was skeptical of dating a pro football player, but she soon learned Gerald was much different than the playboy pro image she had in her head.

Diane learned Huth’s primary motivation was his family at home in Indiana. He sent money from his Giants’ paychecks home to support his mother. His needs always came second to the needs of those closest to him.

“He tried to help everybody,” Diane said.

His selflessness made him a better offensive lineman. In his rookie season for the Giants he blocked for star quarterback Frank Gifford and halfback Alex Webster and was coached by the legendary Vince Lombardi. The Giants beat the Bears 47-7 in the 1956 NFL Championship. Gifford would later personally thank Huth’s family for Huth’s efforts to keep him safe on the field.

Huth and Diane had started dating that season and quickly fell in love. Gerald hesitated at the idea of marriage because his responsibility to his family in Indiana was too great. Diane said she was willing to accept a share of that responsibility if it meant she could spend her life with him. The two were married in 1958.

Leading headfirst

After Gerald’s championship season with the Giants he was drafted into the U.S. Army and was deployed in Germany for 18 months. There, he coached the Third Division, Fourth Infantry team to a European Championship.

Upon his return in 1959, the Giants traded him to the Philadelphia Eagles. After he won his second championship with the Eagles in 1960, Huth was selected by the Minnesota Vikings in the 1961 NFL Expansion Draft. In Minnesota, the tricks of Huth’s trade were on full display.

In May 2010, the Philadelphia Eagles celebrated the 50th Anniversary of the 1960 Championship team. Huth and several of his old teammates returned to Franklin Field to commemorate the championship.

At 5’11”, Huth had to use every advantage he could to move defenders. On the first block of each game, Huth liked to aggressively use his head to make his defender think twice about messing with him the rest of the game. This style of play led Huth to acquire a whopping eight cracked purple Vikings helmets.

Huth had plenty of concussion stories to accompany the plastic shrapnel. He wrote Diane letters sharing how he was knocked unconscious on a play and returned shortly afterwards. Teammates would later share how he would frequently ask, “What’s the next play?” or “What am I supposed to do?”

Huth retired from football in 1964 at age 30. By then, Gerald and Diane had four children: Sharon, Gerald II, Carol, and Kathleen. The family moved out to Garden Grove, California and Huth began a career with State Farm insurance. The new Huth household resembled the farms of Huth’s youth with animals abound.

“He was, pardon my expression, a real hardass when it came to playing football,” Kathleen said. “But when it came to family and friends, he had a heart of gold. He would give you the shirt off his back.”

Kathleen remembers her father driving the family car after a skiing trip in Mammoth when a horrible snowstorm hit and caused a huge backup of cars. Huth took out a shovel and dug the family car out and then proceeded to dig other cars out as well. The Huth family even had to urge Gerald to stop shoveling others and start driving home.

Huth had strict rules for his children, all born out of the virtues he internalized along the way of his success story. He valued hard work, honesty, and education. Huth went back to school to finish his Wake Forest degree in 1960 and saw what it had done for him. He encouraged Diane to get her accounting degree once they were established in Southern California. His support of Diane’s education led her to become CFO for an international company.

He very much had a lighter side as well and his family says he loved to laugh, even if he was the butt of the joke.

“Not my father”

Throughout life Huth possessed a great intelligence hidden by his characteristic humility. But suddenly, he was slipping.

In his late 40’s, Huth often found himself in the family’s garage unsure why he entered in the first place.

Violent outbursts came next.

“One moment you would be talking to him,” said Kat Willis, Huth’s daughter. “The next moment, he’d be yelling at you for something in your life going on and then you’d start taking it personally and it would get you upset.”

Huth’s problems only grew more intense. Once, he stepped out of the house to visit the mall near the family’s home. Hours later, he called Diane in a panic. He could not find where he parked the car.

When Diane arrived at the mall, she found the car right where Huth would have always parked it. Driving was no longer an option.

Diane felt immense pain as she slowly lost the man who walked in with the Ballantine beer all those years ago. She was heartbroken but took it upon herself to do the best she could for Huth.

“He needed me,” Diane said.

Huth usually called Kat “Kathy.” By his mid-50’s, he started calling her “Carol,” confusing her for her sister.

Huth’s memory problems began to infiltrate his work life. He struggled to remember appointments or keep any of his files straight. He was put on permanent disability from State Farm and retired at age 57. He and Diane moved to Las Vegas when she retired in 1999.

The family enrolled Huth in neurological testing to determine what was causing his decline. Huth’s problems were atypical of an Alzheimer’s case. The best doctors could assume was that he was suffering from advanced dementia. In the mid-2000’s, CTE from Huth’s football career was never discussed.

Football helped lead to fleeting moments where the family had the Huth of old back. Kat’s second husband was a football junkie and was excited to meet his former champ of a father-in-law. At their Big Bear vacation home, her husband watched clips of the 1960 NFL Championship. Huth could still give a thorough play-by-play of the game and rejoiced after big plays just as he had when the plays happened live.

“My second husband didn’t really know the father that my father was,” said Kat. “He was a different person. And it makes me sad because my husband’s very much like my dad. It was sad that he couldn’t have that connection.”

Glimpses of the old Gerald also came through when he was with his pets. He had dogs all his life, including three different miniature dachshund named Heidi. Diane gave Heidi III to Huth for his 50th wedding anniversary, a gift he would repeatedly say was the best he ever received.

On November 20, 2010, Huth was inducted into the Wake Forest University Sports Hall of Fame during a halftime ceremony of a game against Clemson. Upon returning home from the ceremony, Huth fell off a curb at his Las Vegas home and fractured his tibia. He was taken to the emergency room and later sent to the hospital for rehabilitation.

While Huth was in the hospital Diane received a phone call. Four attendants were required to hold Huth down in the facility. He was too violent to come home and was moved to a memory care facility.

Huth’s months in memory care were demoralizing for him and his family. When his children visited, Huth told them his presence in the facility meant he was “at the end of the line”. Diane continued visiting him daily, and each time she had to leave alone. Huth could not grasp how his violence precluded him from living with Diane.

On her last visit, an incensed Huth said, “You’re always leaving me. Why don’t you get a [expletive] divorce?”

On February 11, 2011, Huth died of a blood clot in his lung. He was 77 years old.

“It was difficult to see him go the way he did. I just loved the guy,” Diane said. “I still do. I tell him that every day. He was the best thing that ever happened to me.”

Relief

After death, Huth’s brain was sent for study to the UNITE Brain Bank. Huth agreed to donate his brain before his death in hopes research could explain why he had such problems in the last decades of his life. Huth’s posthumous brain donation was his last act in a lifetime of generosity.

“He was such a generous man,” Kat said. “And I know that if he knew the effect that his legacy could have and the changes that they could make with football based on him and all of the other Legacy Donors, I know that he would want to be a part of that very special group.”

Kat and her family were touched by the care and delicacy the Brain Bank team took with Huth’s brain. Researchers at the Brain Bank diagnosed Huth with Stage 4 (of 4) CTE. The diagnosis brought relief and the gift of knowledge to the family. There was a reason for Huth’s changes.

“My dad was such a kind and loving person,” Kat said. “But he could be so mean. And that wasn’t my dad, but I didn’t know what was wrong with him. Knowing that he had CTE was a relief because I knew it wasn’t his fault.”

Diane profoundly misses her husband of 53 years and the countless memories the two made together. She still has Heidi III as a living symbol of her and Gerald’s union together.

For other partners in her shoes, Diane preaches patience.

“I would tell them to be very, very patient,” Diane said. “Try to understand that what you’re dealing with truly isn’t them. It is their brain and their brain is not functioning properly.”

Kat has given to CLF every month since 2012 and has all her gifts matched by her employer. She is proud to have her father in the group of hundreds of Legacy Donors who have contributed to CTE research and awareness.

“CTE is a real thing,” Kat said. “And all of these legacy donors that have donated their brains have paved the way to help the future and to help people understand how devastating this disease can be.”