Debbie Mandigo

Bozidar Darko Maric

Jason Marshall

Richard Martin

Manuel “Mac” Martinez

Matthew Martinez

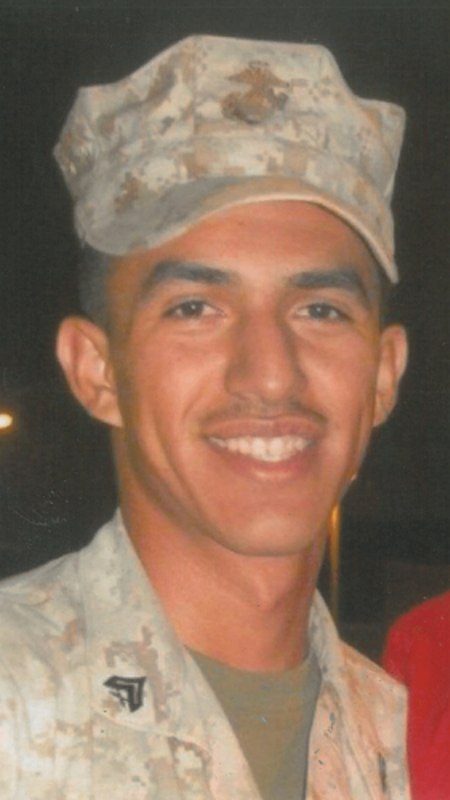

When passersby walk by the Martinez family’s home in Reedley, California, they come across a memorial for Matthew Martinez. Some visitors drop flowers next to Matthew’s monument, honoring the young man who grew up intrepidly exploring the valley’s natural splendor. Many salute his United States Marine Corps plaque, remembering the former Iraq War Veteran, gone too soon.

In the last 10 years, Carmen and Dale Martinez have developed many coping mechanisms to protect from the pain of their son’s death. They are comforted to know Matthew lived a robust 22 years, full of adventure, novel experiences, and so much laughter. They can look at Matthew’s son Noah, his doppelganger in both appearance and spirit. They can remember how Matthew did what he set out to do from a young age by serving his country.

But coping has its limits.

“As parents,” Carmen said, “we are not equipped to send our kids off. It’s supposed to be the other way around.”

As much vitality as Matthew and the countless other Veterans lost to the invisible wounds of war gave in their time on Earth, we could help them have even more, says Dale.

“These heroes who have served – they all have a story to tell. We want them to be healthy. We want them to seek help when they need it so they can share their stories of their life to their children and their grandchildren.”

Matthew Martinez was born on September 19, 1988. His parents fondly remember young Matthew’s zest for life.

“He was just a cool guy,” Carmen said. “He always wanted to please and do good for everybody.”

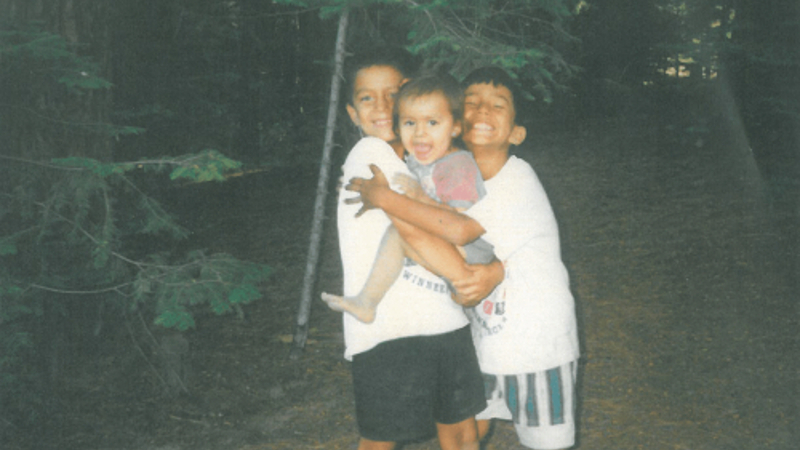

From a young age, he took advantage of the nature around him in California’s Central Valley. He was notorious for starting lemon fights on the Martinez family’s 25 acres of citrus orchards – hurling the fruit at his siblings and cousins.

Matthew was in his element during family camping outings at Sequoia or Yosemite National Parks. The vast landscape around him offered a chance to swim, hike, run, climb, and extract as much fun as he could from the world.

“He’d be the first one up a rock,” Carmen said. “Like Spiderman.”

After school, Matthew loved playing sports, dirt biking, working on cars, and taking camping trips with friends.

Many of the men in the Martinez family served in the United States Armed Forces. At the family’s many gatherings, Matthew listened closely as his grandfather, great uncles, uncles, and cousins shared stories from their time overseas.

Matthew was 12 years old on September 11, 2001. He watched many of his cousins immediately enlist in the war and serve in the initial invasion units in Iraq. When Matthew was a sophomore in high school, he decided to enlist in the U.S. Marines.

“He took a lot of pride in his family’s history of service,” Dale said. “He wanted to make us proud for his service and by his service. And he did.”

Martinez entered the Marines two months after graduating from Reedley High School. He graduated from boot camp in Camp Pendleton in San Diego in October 2006. A year later, he was deployed to Iraq.

A platoonmate of Matthew’s from his first deployment remembers a sudden thud to the back of his head while he was looking out into the distance.

The thud came via Corporal Martinez, who threw an orange at the platoonmate’s head. 7,500 miles away from home, Matthew found a new citrus to play with.

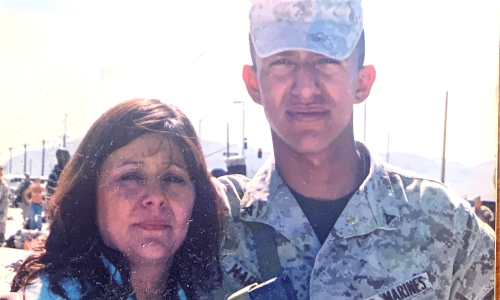

Matthew wrote home often during his first deployment. Over occasional video calls, Carmen and Dale saw the same joyful Matthew they raised for 18 years, albeit a bulkier version.

The first tour ended in May 2008. Matthew was back on U.S. soil, stationed a seven-hour drive away from home in Twentynine Palms, California.

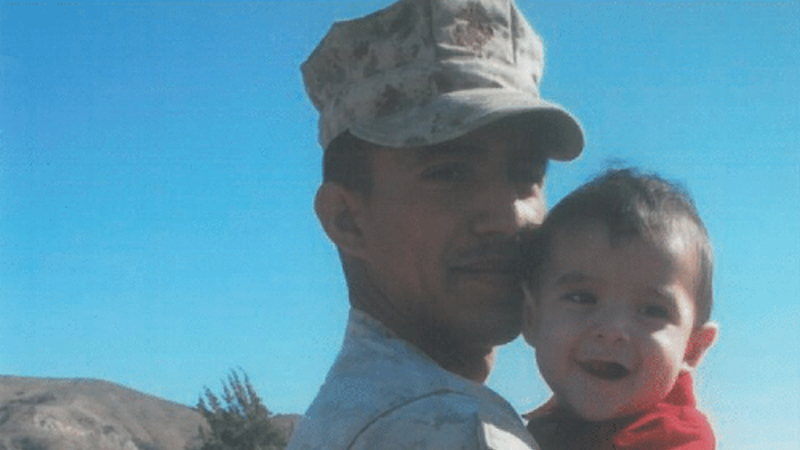

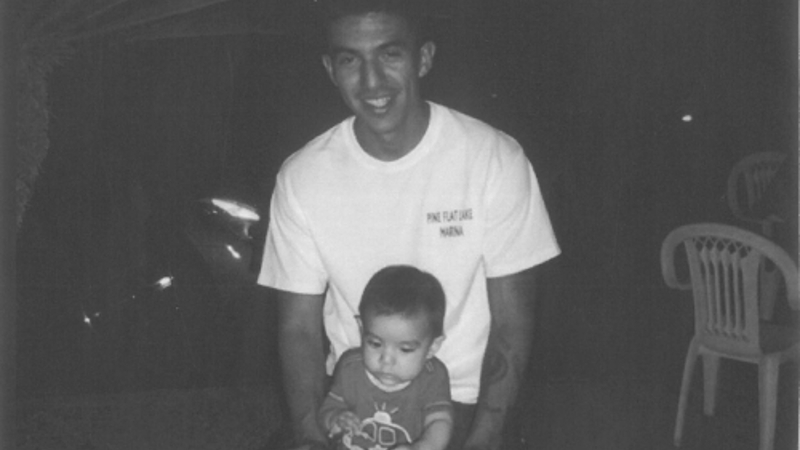

In February 2009, Matthew’s son Noah Scott Martinez was born.

Once Noah was born, Matthew went home every chance he could, flooring the gas pedal from Twentynine Palms to Reedley. Matthew adored Noah and loved playing with him.

“Noah was his pride and joy,” Dale said.

Matthew left for his second deployment, a marine expedition unit (MEU), in September 2009. The MEU represents a dark period for the Martinez family’s communication with Matthew, as letters home were less frequent, and Matthew had less access to video calls than he did on the first deployment.

Dale and Carmen are still unsure about the specifics, but they know Matthew experienced a fair amount of injury on the MEU. They know he suffered several falls over the course of the deployment. They also know he operated heavy artillery – regularly putting him in range of blast waves that emanate from firing weapons.

Martinez returned from the MEU deployment in May 2010. He was honorably discharged from the service three months later. He was finally coming home for good.

“We were elated,” Carmen said. “We didn’t have to worry about him getting blown up, shot at, or taken prisoner. He was safe.”

Carmen looks back on those first few months of being reunited with Matthew as a “honeymoon period.” When he first came home, Martinez told his family he wanted to grow his hair out and relax for the first time in years. But for the next 10 months, he struggled to find such peace.

“It’s a disease that hides,” Carmen said. “He was fighting silent battles all while we thought everything was fine.”

The first sign of trouble was the headaches. Matthew frequently complained to his parents about headaches so painful he couldn’t sleep, and he rebuffed every time Dale and Carmen suggested he take medication and seek medical services.

Matthew was effortlessly cool and easygoing growing up. He loved life too much to be fazed by much of anything. After he was back home, Carmen was stunned to see her son get so upset when he discovered his burger order had been mixed up.

“The mood swings were probably when we first thought, ‘Whoa’,” Carmen said. “This is not Matt.”

There was a distance between pre-deployment Matthew and post-deployment Matthew. A similar distance emerged between Matthew and his son.

In between his first and second deployments, Matthew wanted as much to do with Noah as he possibly could. But after the MEU, Dale and Carmen noticed Matthew didn’t possess the same energy when he cared for Noah.

Matthew could tolerate caring for Noah for brief periods, but his patience grew thin over time due to the stressors of raising a toddler. When Noah began to fuss, Matthew would become agitated and leave the room.

Dale had seen this before. His father was a Vietnam Veteran and battled PTSD for much of his childhood. When Dale saw his son suffer from headaches, nightmares, and anxiety, he urged him to seek professional help.

Before Matthew’s service, he and his mother had a close relationship. They could talk about anything. But when Carmen asked him questions about his deployments, Matthew reassured her she didn’t need to know about what he experienced.

“That’s kind of how it works with Veterans,” Dale said. “They protect their loved ones from some of that exposure.”

Finally, in April 2011, Matthew and a cousin went to the VA together. There, Matthew received a referral for a psychiatric appointment he’d never make it to.

On Friday, June 3, 2011, Matthew erupted in rage while working at the family business over a simple matter. That night, Matthew made peace with his father over the outburst.

The following morning, Matthew woke up with a headache and took a nap in his parents’ bed. Hours later, Matthew died in his sleep of a brain hemorrhage. He was 22 years old.

In the hectic wake of tragedy, the Martinez family’s search for clarity led them to Dr. Ann McKee, Director of the UNITE Brain Bank. Dale spoke with Dr. McKee and arranged for her to study Matthew’s brain.

“I knew something wasn’t right,” Dale said. “This was a strong kid, 22 years old. How the heck does his brain explode?”

Dr. McKee found changes suggestive of CTE in Matthew’s brain. The Martinez family remembers Dr. McKee explaining how the findings of Matthew’s pathology report were unlike anything she had ever seen. She likened Matthew’s brain to that of a much older person. She theorized how the overlapping of Matthew’s PTSD with his likely history of TBI may have contributed to his sudden death.

The results brought a wave of emotions upon the Martinez family.

First, there was relief. If Dr. McKee did not report any changes to Matthew’s brain, Matthew’s last 10 months would have devastated Dale and Carmen.

Then, there was clarity. The mood swings Matthew exhibited after he returned home seemed to come from an entirely different person than the man Dale and Carmen raised. They often wondered what they had done to upset their son so much.

“Now we know it wasn’t us,” Carmen said. “There was so much more going on in his head.”

Finally, there was pride. Matthew was fiercely proud of his and his family’s military service. The family is assured he would have been proud to be part of research that will help other Veterans manage the symptoms of TBI, PTSD, and possible CTE.

The family supports CLF’s Project Enlist, which recruits and conducts outreach to the military and Veteran communities to encourage them to donate their brain for research. More research will beget ways to prevent, diagnose, and treat the invisible wounds of war Matthew endured.

Carmen and Dale urge other Veterans to embrace vulnerability and seek help.

“PTSD is a silent killer,” Carmen said. “Matthew was screaming out and no one could hear him because he could only hear himself.”

For parents of other struggling Veterans, they suggest persistence. If you see your child struggling, raise the issue and advocate for seeing a professional. Silence only contributes to the crippling stigmas of mental health in the military community.

Carmen Martinez’s favorite quote is also her wish for her son’s legacy.

No day shall erase you from the memory of time.

June 4, 2021 will mark 10 years since Matthew Martinez’s death. The Martinez family is planning a gathering to celebrate Matthew’s life and preserve his memory. Friends and family will join to reminisce on a life cut far too short.

“He was a hero to us,” Dale said. “He forever will be.”