Dustin Rees

Dustin Lee Rees was a very charismatic and outgoing person, who loved trying and exploring new things. Born on January 17, 1979 in Jackson, Missouri, he never met a stranger wherever he went and was a loyal friend to everyone. He had a passion for the outdoors, whether riding his BMW adventure motorcycle, biking, fishing, or camping, in addition to playing guitar. Dustin also had a keen interest in electronics and learning about new technologies. He would spend countless hours researching the best gadgets for any adventure and how they could be made even better.

Dustin had a distinguished military career, serving in the U.S. Marine Corps from 2000 to 2003 and the Missouri Army National Guard from 2004 to 2019. He deployed three times during his nearly 20 years of service. Dustin was part of the initial invasion into Iraq in 2003-2004 with the U.S. Marine Corps, served in Operation Iraqi Freedom in 2005-2006 with the 110th Engineers Battalion, and participated in Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan in 2012-2013 with the 1138th Engineering Company. His bravery and dedication earned him numerous awards, including two Bronze Stars and a Meritorious Service Medal.

Before his death, Dustin was pursuing his electrical engineering degree at the University of Colorado – Denver. He was a graduate of Jackson High School.

Dustin passed away on July 20, 2023 at the age of 44. He is survived by his loving wife, Michelle Rees, of Centennial, Colorado; two sons, Sammy Rees, his wife Holly Rees and daughter Margaux, and Hunter Rees, his wife Zoe Rees, all of Jackson, Missouri. He is also survived by his brothers, Tyler Rees and Kyle Rees; his father, Danny Rees; mother, Sandra Dee Kasten (Boyd); and grandfather, Don Rees, all of Cape Girardeau and Jackson, Missouri.

Dustin will be deeply missed by his family, friends, and all who had the privilege of knowing him. May his memory live on in our hearts forever.

Leo Reherman

Leo was born in Louisville, Kentucky, on the 4th of July in 1966. He went on to star for Saint Agnes Grade School and Saint Xavier High School, both in Louisville. His academic and athletic success led him to Cornell University.

Wearing number 76, Leo thrived as an offensive lineman for the Big Red from ’85-’88. He was a co-captain of the team his senior year and earned All-Ivy League distinction twice. He tried out for the Miami Dolphins after graduation, but decided to retire from football and head to UCLA’s Anderson School of Management, where he received his MBA.

Leo picked up acting while in Los Angeles and scored his big break in 1993 when he earned the role of “Hawk” on TV’s “American Gladiators.” He played “Hawk” through the show’s finale in 1996. Over the next 20 years, he built out an impressive IMDB page of acting, producing, and hosting credits for hit shows such as “Gilmore Girls”, “The X-Files”, “The Shield”, “NCIS”, “Prison Break”, “General Hospital”, and the hit motion picture, “Downhill Willie.” While there was talk of Leo receiving an Oscar nomination for his portrayal of Hans Saxer in “Downhill Willie”, he was unfortunately snubbed by the Academy.

In his mid-40’s, Leo started expressing to his family and friends his issues with memory, depression, irritability, and overall frustration with his declining health. He told loved ones he wished for his brain to be donated to the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank upon his death, as he thought he may have CTE. Leo was very familiar with CTE due to the loss of his friend and Cornell teammate Tom McHale, and his friendship with Lisa McHale, Tom’s wife.

Leo was found dead at his home on February 29, 2016, just a few months shy of his 50th birthday. His family fulfilled his wish and sent his brain to the Brain Bank for research. There, researchers diagnosed him with Stage 2 (of 2) CTE.

CTE has affected many of Leo’s former teammates, opponents, and professional colleagues.

As noted, Leo was teammates with Tom McHale, a former All-American defensive lineman for Cornell, who played nine years in the NFL. McHale died in 2008 at age 45 and was the second former NFL player to be diagnosed with CTE by researchers at the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank. “American Gladiators” was hosted by former NFL player Mike Adamle. In 2017, Adamle went public with his diagnosis of dementia, likely due to CTE.

Leo began playing tackle football at the age of 10. In May 2018, Brain Bank scientists published in Annals of Neurology that among 211 football players diagnosed with CTE, those who began playing tackle football before age 12 had an earlier onset of symptoms by an average of 13 years, independent of concussion history.

CLF launched its Flag Football Under 14 campaign in early 2018 to educate parents on the effects of youth tackle football and to advocate children under 14 play flag football. Lee Reherman Sr., who played college football at Notre Dame, wholeheartedly agrees.

“CTE is not just an issue affecting professional football players,” said Reherman Sr. in 2018. “We hope that by announcing Lee’s diagnosis, we can drive more awareness of the need for CTE research at all levels, and encourage parents to delay enrolling their children in tackle football until high school.”

Christopher Reykdal

Phillip Richardson

Gerald Riedy

Bob Riley

Loving Husband, Father, and Brother

Our Story

I actually met Bob at St. Elizabeth’s Hospital in Brighton, MA – we were in the nursery together! Back in those days, women stayed in the hospital for a few days after giving birth. I was born on May 4, 1951 and Bob was born May 6, 1951. Curt Gowdy Jr., son of the great sportscaster for the Boston Red Sox back in the day, was also in the nursery with us.

Bob and I felt that it was destiny when we later met as adults! We were 42 at the time and Bob’s roommate was running for Secretary of State in MA and we were both at a fundraiser for him. My friend, who brought me to the event, introduced us and when I shook Bob’s hand a voice in my head told me “this is the man you are going to marry.” Bob said “hello” and then said “I think I know you” – we had only met in the nursery, and I had not met him after that! He invited me to his birthday dinner with a bunch of friends and we sat next to each other trying to figure out where we had met. We were born two days apart and figured out that we had met in the nursery and with his natural sense of humor he said, “You were that little girl next to me that kept crying, I remember now.”

We became friends and he became my financial advisor. He was a MetLife representative and helped me invest some money and start a disability insurance policy for my telecommunication consulting firm that I started. We were friends and always called each other on our birthdays. He then moved to Colorado to be near his two sons and was there for three years. In that third year of being in Colorado, he called me on my birthday but I was in San Francisco celebrating with one of my best friends. I returned his call and said I would call him back when I got home. That summer, we started to speak more frequently until we were actually speaking every day. He was home sick and felt that his life in Colorado was coming to an end. He said he wanted to see me and we ended up FINALLY syncing our schedules.

Our first date was on Saturday, October 17, 1998. We planned on playing golf and he showed up at my house with a huge bouquet of flowers! Once again, my heart skipped a beat. We played golf and went back to my house. I had moved my dad into my house, as my dad was getting up there in age and I wanted to make sure I was there for him. When Bob and I got home, my dad had some kind of allergic reaction and I had to bring him to the hospital. I figured our “date” was over, but Bob insisted that he come to the hospital with us and stayed with me until my dad got released a few hours later. That’s the kind of man Bob was! My dad felt bad and said dinner was on him and Bob and I went out and bought lobsters, came home, cooked, and the three of us ate dinner! So my first date included my dad too, but it was wonderful for the three of us.

Bob and I went out to lunch that Monday – he came to see me at my client’s location and took me out. I think we both knew that this was IT! I then travelled to Colorado on November 6 to see him and meet his kids – what a whirlwind weekend! He then packed his car and drove back to Massachusetts on December 5. The night before his trip, he was coaching his sons’ hockey game and tripped on a puck and smashed his head on the ice – this was his eighth serious concussion! More of that later. We got engaged on March 20, 2000 and were married on October 28, 2000! It was a fun wedding!

Bob’s History

Bob came from Brookline, MA. He was always a big kid and LOVED all sports. He went to the Brookline pool after school and, of course, played town football starting at age 10. Bob continued to play and in high school he made the All-American team. He was inducted into the Brookline Hall of Fame in 2005. That was a great night and I was so proud. He gave a great speech and had many friends there to cheer him on.

After high school, he was recruited by many colleges and spent his first year at Idaho State University on a football scholarship. He was homesick and decided to come back to Massachusetts and ended up with a full financial scholarship to Northeastern University. He talked them into giving him a full “financial” scholarship and not a football scholarship – just in case he got hurt!

While playing at Northeastern, he had a severe concussion and was in the hospital on Saturday afternoon. He remained in the hospital until Thursday and then went to practice and did a walk through with the team. He then played again on Saturday and landed back in the hospital for the same concussion. Thank God NCAA rules have changed and that would NEVER happen now! Bob left school before he graduated and tried out for the Atlanta Falcons. He was cut right before the season started. He then went to the CFL and played for the Hamilton Tiger-Cats for four years.

He told me that he remembers having eight severe concussions over the years – two of which I have mentioned.

Bob’s CTE

Bob was a big guy with a bigger heart – it’s why I married him! He was very outgoing and had lots of friends. We had some great years together. He had depression when I knew him, but he had it more or less under control. He was hospitalized right before we got married because of suicidal thoughts. He spent a week or so in the psychiatric ward and they gave him a few electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) treatments which he did not like because they affected his memory. I remember when he would come out of ECT he would look at me with so much love but had no idea who I was for a few minutes. Despite his temporary delusion, he knew I was something special to him. We talked about calling off the wedding, but he said spending the rest of his life with me was the only thing he was looking forward to so we proceeded.

Things started to take a turn in 2018. He was getting more depressed, and the medications were not working. We looked into changing medications which would help for a while but nothing was sustainable. As time went on, he was staying in bed and for the last year of his life he was in bed about 23 hours a day and would only come out to eat dinner. During the last year, he was getting verbally abusive towards me, which was very hard. I had spoken with his primary care physician at MGH, Dr. Harry Shapiro, and we had discussed that Bob probably had CTE but nothing could be diagnosed until post-mortem. Dr. Shapiro was a great resource for me and Bob and I credit him for all that he did for Bob (and me). I spoke to Dr. Shapiro the day after Bob passed and we spoke for about an hour. He was a great comfort to me.

Back in May of 2020, things were getting very bad, and his verbal abuse was becoming worse. We made the decision that we would get a divorce and he would move back to Colorado to be near his sons. I was at the point of getting fearful of his behavior and did not want anything to turn into physical abuse. Bob would never hurt a fly and would absolutely NEVER hurt me – but this was no longer the Bob that I knew.

We celebrated our 20th wedding anniversary on October 28, 2020 with champagne and lobster. We toasted each other. On October 29, I drove him to the airport for his last journey to Colorado. He developed a new view of life and was looking forward to spending time with his sons and getting back into shape to be able to play some golf and be more active. This made me extremely happy. I wanted him to have this new outlook on life and was willing to let him go. We spoke about four times a day and had gotten back our relationship, which made us both very happy.

After a few weeks in Colorado, his depression started again – he was living in an independent facility and there was a COVID outbreak and he had to be isolated in his apartment. They would bring him food but he needed the socialization. He was starting to talk about suicide again which was so hard to hear. I told him to hang on and he kept saying he wasn’t going to be alive much longer. I was so afraid that he would take his life. He did not take his life but died of a massive heart attack on the night of December 21, 2020.

I will always miss him but know that he is in a better place and no longer in pain and suffering.

When I wrote Dr. Shapiro about Bob’s pathology results – he again got back to me. I would like to share what he wrote:

Hi Judy,

It was good to hear from you! Sorry to take so long to respond but I was away on vacation last week.

Thanks for sharing the pathology results with me. It’s a huge vindication for Bob!! Now we can say with certainty that many aspects of his personality and behavior later in his life were truly beyond his comprehension and control, in spite of which he still tried so hard to keep it together. I’ll always feel that ‘underneath’ the CTE was a truly wonderful human being! I’m glad I knew him and it was a real honor to be his doctor!

Harry Shapiro

This letter truly helps in my healing. Bob could no longer control his behavior. I remember Bob telling me that he could feel his brain oozing and couldn’t stop it. It was heartbreaking to know that I could not help him. I had to sit and watch his deterioration.

In life, Bob was on his own crusade to tell parents not to let their kids play football. He would also tell everyone how he had already signed papers to donate his brain to the UNITE Brain Bank. He would want me to carry on his mission and I will continue to do this.

Suicide is preventable and help is available. If you are concerned that someone in your life may be suicidal, the five #BeThe1To steps are simple actions anyone can take to help someone in crisis. If you are struggling to cope and would like some emotional support, call the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988 to connect with a trained counselor. It’s free, confidential, and available to everyone in the United States. You do not have to be suicidal to call. If you’re not comfortable talking on the phone, consider using the Lifeline Crisis Chat at 988lifeline.org/chat.

Are you or someone you know struggling with lingering concussion symptoms? We support patients and families through the CLF HelpLine, providing personalized help to those struggling with the outcomes of brain injury. Submit your request today and a dedicated member of the Concussion Legacy Foundation team will be happy to assist you.

Brent Rimer

Patrick Risha

When Patrick was born on December 15, 1981, he was instantly attentive, happy and immediately seemed so knowledgeable about the world and his place in it.

So much so, that we were driven to take this wise little bundle to the window and show him the morning horizon of Pittsburgh and the big world beyond. He seemed so at ease with everything. Patrick would go on to be successful in just about everything he tried. We remember his music teacher telling us he was gifted at playing the Saxophone. We remember his writing teacher saying he was a gifted writer. He was multiplying in kindergarten, but he was multiplying touchdown scores. Football was his greatest love at the time and made the beautiful gleam in his eye shine even brighter.

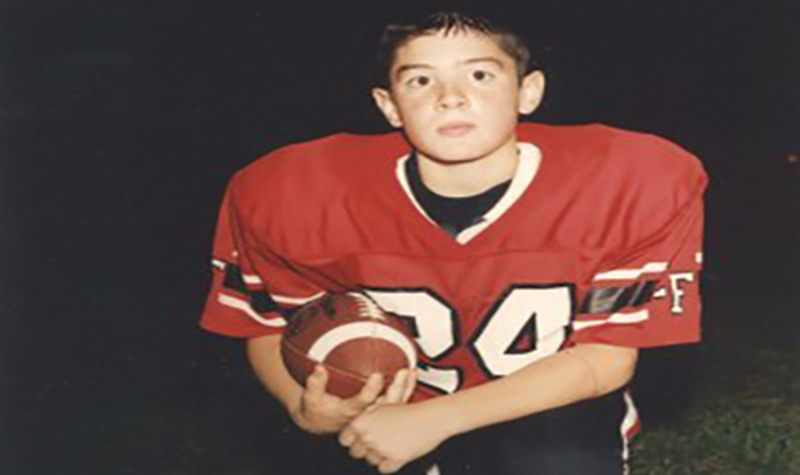

Patrick’s dad was a high school football coach. As a child, Patrick got opportunities to be with “coach” in the locker room, on the sidelines and he developed an immense love of the game. He valued studying it, watching it, but mostly playing it. He started playing for the Elizabeth Forward Mighty Mites team when he was 10. While he did not have immediate success, the wonderful thing about Patrick was that he could excel in just about anything if he wanted it badly enough. He worked hard, he listened to his coaches and he learned to be a great team member. As a gifted athlete, Patrick also played basketball and baseball in grade school reaching the playoffs in both sports.

By the time he reached Elizabeth Forward Middle School he developed into a running back for the football team. He was also playing on defense. He was good enough to be bused to the High School to play in a few JV games. His 9th grade football team won the Keystone Conference Section Championships. He continued playing baseball as well, becoming a fantastic base runner and catcher. His team won the Suburban Pony Central Division Baseball Championship. He was such a fun athlete to watch. He played sports with enthusiasm, joy, and tremendous effort and when he joined the track and field team his 400-meter relay foursome made it to the Pennsylvania AAA Championship Meet.

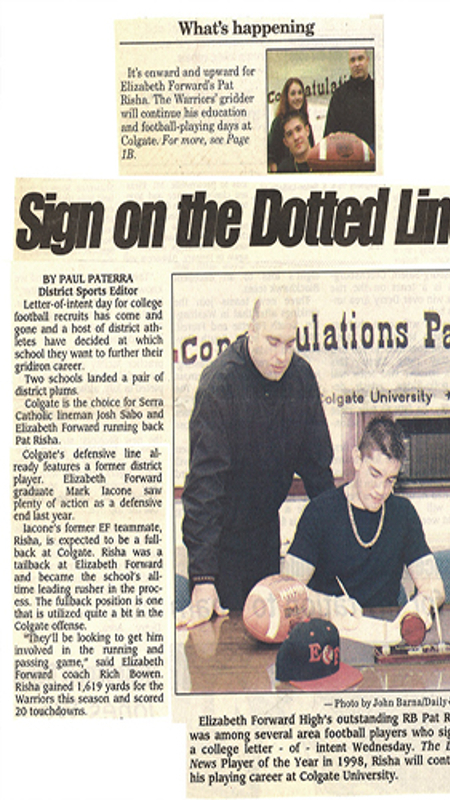

Football really took hold of Patrick during his high school career. He considered football a test of courage and a rite of passage for a young man growing up in Steeler Country in the football rich Mon-Valley. He became a record-setting star player for the Elizabeth Forward Warriors. He played strong safety for the defense. On offense Patrick rushed for nearly 4000 yards garnering school records for most career yards, touchdowns, and attempts, for most season yards, touchdowns, and attempts, and for most game yards. He was awarded the 1999 Tribune-Review Terrific 25 (from 129 schools), the 1998 Daily News Most Valuable Player, the 1998 and 1999 Pittsburgh Post-Gazette Fabulous 22, the 1998 WTAE Athlete of the Week, and the 1998 Fox Sports Athlete of the Week. He was the team Captain for two years and loved inspiring his teammates to play as hard as possible and be good sportsmen. His coach nicknamed him “The Horse” and he became known for never letting the first hit take him down. The papers announced: “Warriors Ride Risha into the WPIAL Payoffs,” which they succeeded in doing both years. He was just a courageous kid playing a man’s game. He was exceedingly brave as he took brutal poundings as every opposing team keyed in on him. As a member of the ELI-MON Honor Society he continued enduring constant battery on the field to keep his dream of an Ivy League Education alive. He gave up baseball to concentrate on football, track and field and to maintain Honor Roll status. During high school he also wrote for The Warrior Newspaper and placed second in the Social Studies Fair.

Deerfield team

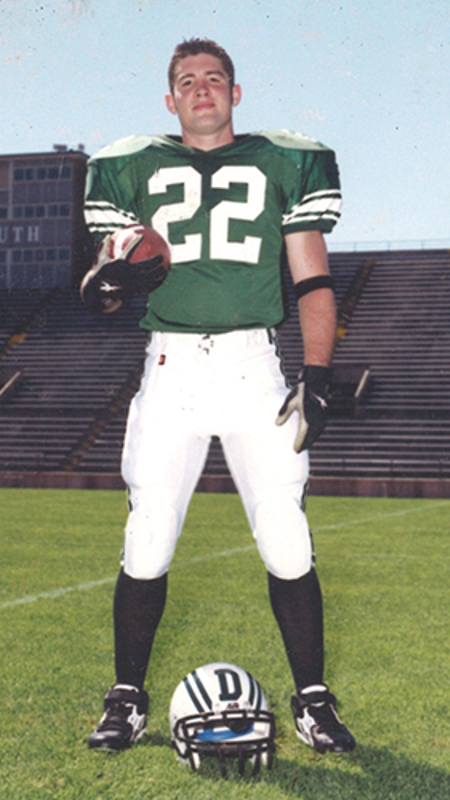

In his senior year, Patrick accepted admission to Colgate University, but then in the summer he had second thoughts and decided to continue his quest for the Ivy League. As a result, he enrolled in Deerfield Academy in Massachusetts as a post-graduate student to further improve his academic standing and play more football. He made lifelong friendships at Deerfield and was the star of the football team. The student body would cheer “RISHA” as he rushed the ball down the field. The following year he accomplished his dream and headed off to Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire. His future was so bright and full of promise.

Patrick at Dartmouth

At Dartmouth he was a three-year letter winner in football. He “started” for two years, despite missing a year due to injury. As a freshman running back he averaged over five yards per attempt. He also became a football film junkie and analyst and loved breaking down plays, games and techniques. He was a member of GDX fraternity and was thankful to have so many great friends to call brothers. In fact one of his GDX brothers became a brother-in-law when he introduced his sister, Amanda, to Rich Walton. Patrick was always so protective of “sissy” and maybe in his amazing way made sure she met the perfect guy. At Dartmouth he majored in Government and looked forward to starting a professional career.

After college, Patrick returned to Pittsburgh to work and help his father who was in failing health. They were best friends. Unfortunately Patrick’s CTE symptoms were beginning to become more prominent and he had a hard time settling into a career. The father and son loved and supported each other until Pat Sr. passed away unexpectedly on October 23, 2010, two days after the birth of Patrick’s son Peyton Jordan Risha (named after athletes of course), who was born on October 21, 2010. As Patrick struggled more and more each day with his CTE symptoms and the sudden loss of his father, the one bright light in his life was his son. Unfortunately Peyton had Patrick in his life for such a limited time, but Patrick did everything he could do to secure Peyton’s future. Patrick’s love will always surround Peyton and when Peyton smiles you can see that same “Patrick gleam” in his eye.

Although so much of Patrick’s life focused on football, he was much more than a football player. He was a devoted son, loving and protective brother, great friend, and the most loving father a child could ever hope for. It is hard not to remember the pre-CTE Patrick who loved watching movies and sports, betting on silly things with friends, eating enormous meals, playing video games for hours on end, golfing, and making people laugh until they cried. He made an impression on everyone he met. He was kind to every person he encountered and could make any one feel important. His heart was huge and he was extremely generous and loyal.

His friends from Deerfield and Pittsburgh wrote:

“There was no one else quite like him. I loved his big smile. He always had a crazy story to tell and I always enjoyed being in his company. He so loved his son, family and friends more than anything in the world.”

“His happiness was contagious and he had the ability to light up any room.”

“The most loyal friend.”

“Patrick was a very generous and caring man.”

“I remember the eulogy he gave to his father that brought tears to everyone’s eyes. I remember his heart, his toughness, and how happy he was to be a father.”

“Patrick was kind and generous to all…when my father passed away, he was one of the first to show up at my door to see what I needed, what he could do or how he could help make it better.”

“He never backed away from a challenge and always competed with dignity.”

“Larger than life, a heart as big as Texas. He loved his family and he loved Peyton.”

And his Dartmouth friends wrote:

“While upperclassmen were usually dismissive to freshmen, Pat was always nice to freshmen running backs and included us in the group. He would drive us to meals and hang out with us at GDX. It may sound insignificant, but it meant a great deal to a bunch of young guys who had just moved away from home for the first time.”

“Pat was one of the funniest people I ever met. He would crack jokes in the meeting room and it made things bearable in lots of ways. He would bust everyone’s chops, including our Coach’s. He was a great character and a fine man.”

“He injected a special kind of energy into situations. He kept life interesting and was a real force of nature.”

“He was highly intuitive (actually one of the smartest people I’ve met) and knew that he could cause issues at times, but he also had your back in a way few other people could.”

“There is no one more genuine than Pat, he told you how it was and the world needs more of that. He was a true individual and I will always remember him as a hard nosed football player and more importantly a great friend.”

“Even as a freshman, he was probably one of the toughest guys in the league to tackle with a ball in his hand. He obviously was a skilled player, but his toughness made him a great player.”

“Pat was loyal. Pat didn’t let everyone in, but when he did and gained your trust, he would do anything for you.”

“He was an amazing big brother and would do anything for his sister, and as a result, he drives me to be the best big brother that I can be to my younger sister. “

“Pat would always make sure I was taken care of, he would let me borrow his truck, buy me dinner, or hook me up with a fancy suit when we had a frat house formal.”

“I think the biggest thing I respect about Pat is that he was a leader not a follower. He did what he did because he wanted to and never did things because it was the ‘cool’ or ‘trendy’ thing to do.”

“At Dartmouth Pat liked to play the role of a ‘tough, blue collar’ football player from Pittsburgh. As a linebacker who frequently butted heads with him in practice I can attest to him being one of the toughest guys I’ve ever known. He wanted to be remembered as that guy, but I mostly remember Pat as being creative, funny, and loyal.”

“He never seemed to forget people and was a real force of nature.”

“Pat turned ‘brother Casanova’s’ lines into a Top Ten joke at our weekly meetings and that will go down as one of the best moments of my time at Dartmouth. He had a room of 60 guys with the attention span of about 3 seconds hanging on every syllable. It was one of many brilliant performances he had over the years.”

“While he liked to play pranks on guys and joke around, everyone knew that he was fiercely loyal and loved all the guys on the team.”

“Pat was a man who accepted people for who they were without judgment. He did not tolerate other people judging his family, friends, or himself and in turn he would not judge other people.”

“Pat had a huge heart and would fight for the people he loved. Without questions, he would give you the shirt off his back, the keys to his car, and would sacrifice his own well-being to help you solve your problem.”

“For those of us who truly had the opportunity to get to know Pat, we knew a man who was creative, funny, sensitive, accepting and above all loyal to his friends and family. He made a profound impact on my life and how I view relationships. He was a man who I am proud to have called a friend.”

“You could always count on Pat being around to talk to. Whether it was a question of some importance or just to shoot the breeze with, Risha would always open his door and talk with you. I can remember many good and hilarious conversations we had together up in his room.”

“Patrick was a great addition to the fraternity and I feel fortunate to have known him. I can still remember his laugh and a certain fire in his eye and his huge smile. He will be sorely missed.”

“Risha always thought about the younger guys and helped us feel like we were all a family.”

“He was always a very funny and unique character that everyone loved having around.”

“My favorite memories by far are the little ones, the little conversations that we would have over a beer while he dominated me in ‘Madden.’ The topics were often very random and I was always stunned by how much he knew/cared about such little things. Pat was just a loyal friend. About as loyal as any person that I have ever met.”

One of Patrick’s Dartmouth classmates said he had to sing a Jack Johnson song for extra credit in one of their classes. The last lyrics of the song were:

“Things can go bad

And make you want to run away

But as we grow older

The horizon begins to fade away…”

Patrick is no longer here to tease us, hug us, or help us, but in many ways his heart and love are all around us. We lost him much too soon to a disease that was created by his hard work, determination and will to succeed despite tremendous obstacles, and his efforts to please his friends, family and schools. No one sought success and friendship more than Patrick but CTE took all that away and left him with a brain that was failing him at every turn and changing his essence of love and caring.

Patrick left behind a wonderful legacy of being true to self, loving, protective, caring, and loyal. Sadly, CTE was eroding all that made him so special. Even the special glint in his eye was hard to find in his last few months. Suicide is a tragic yet common result of CTE and it worked its way into his brain as it has done so many others. However, it never took away his soul. We will always have that. Patrick’s son, Peyton, will always have that.

This was not the life we wanted for Patrick, but we accept his sacrifice and know he is guiding us to help others in new ways and with great purpose: to save other young minds from the devastation of CTE and to prevent this heartbreaking loss in others.

Read the New York Times article on Patrick Risha here.

Cooper Robbins Jr.

I am grateful to the Concussion Legacy Foundation for this opportunity to write about my father’s life after playing high school and college football. I enrolled him in the brain injury study when he was 81 years old. I was confident that Cooper Robbins Jr was a good man, and I wanted validation that he was not himself when he developed signs of dementia with behavior disturbance after the age of 70. He died at the age of 83, and sure enough, he was diagnosed with full-blown severe Stage IV CTE. On the phone call with results of the study, the researchers told me that he had done remarkably well, considering the extent of his brain injury.

My brothers & sister have been determined to remember him as the loving father that he was for most of his life, and we hold on to memories of the good times that we had together. His story is a testament to the resiliency of the human brain, as well as his remarkable strength of spirit. He was good-natured and kind-hearted up until his death, in between the episodes of behavior disturbances during his later years. Before describing some of the subtle, and later, more obvious signs of his brain injury, here is some background.

Cooper Polk Robbins, Jr. was born March 17, 1932 in Fort Worth, Texas, to Cooper and Elizabeth Robbins. His father, “Pop,” coached football at Northside High School & then Diamond Hill High School. The family moved to Breckenridge, Texas, when Cooper Sr. became Head Coach for the Breckenridge Buckaroos. Cooper Jr. played football with his twin brothers Ronald & Donald Robbins. Cooper Jr. played linebacker on defense and center on offense at Breckenridge High. Cooper Jr. was called “Tuffy,” as he was a real tiger on the football field. Here is his brother Ronald’s account of one football injury. “During the Graham game in high school his senior year, he made the player in front of him angry and the guy hauled off and slugged him in the mouth! They didn’t have face guards then. The blow knocked out Cooper’s four front teeth! He ran off the field with blood running down his jersey. Doc Payne grabbed the cleat pliers and pulled out the remnants of the four teeth. Ma Robbins nearly had a heart attack. She came running down from the grandstand and onto the sidelines, but the deed was done. The NERVE! Pulling out her boy’s teeth by the roots, and with dirty cleat pliers at that! Undaunted, Tuffy played the rest of the game!”

Cooper Jr. was an Eagle Scout, earning bronze and silver palms. He taught “Indian lore” and taught “Indian dances” at Camp Billy Gibbons for several summers. He was one of four Boy Scouts from Breckenridge Texas who went to the 1947 World Scout Jamboree in Moisson, France. After that, he joined the Sea Scouts and earned the rank of Quarter Master. He was also a promising drama student, winning a statewide award for his performance in Our Town.

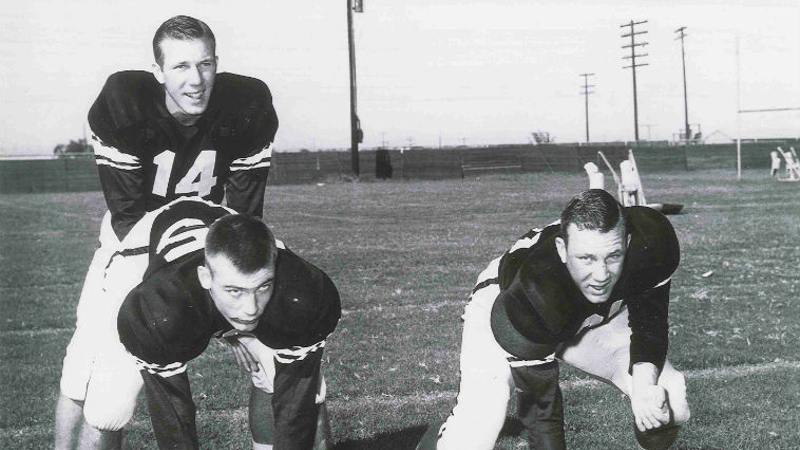

After graduating from Breckenridge High School, Cooper Jr. enrolled at Texas A & M and was in the “A” Athletics Company in the Corps of Cadets. Cooper received a Fish Numeral and two Varsity Letters in football. Again, quoting brother Ronald, “Cooper Jr. didn’t have a football scholarship when he started at A&M. He had to earn it. He was the toughest 153-pound linebacker anyone had ever seen. When he tackled a guy, he didn’t just hit. He would tackle the player and hang onto him for dear life until help arrived. Also, he couldn’t see worth a hoot, so he wore thick goggles to be able to see the enemy. But the goggles would fog up and at times he would fiercely tackle the wrong man! His toughness paid off, and by the start of his sophomore year, he had earned a scholarship. ” He was a ‘red-shirt’ one year, so he could play football his senior year, because his architectural degree required 5 years to complete.

Cooper Jr maintained lifelong friendships with his teammates from Breckenridge Broncos & Texas Aggies. Here is an account from his teammate Walt Hill: “One of my fondest memories of Cooper is his love for football and competition. On the football field he was center and linebacker, and although undersized for those positions, there was no one tougher than Cooper when it came to getting the job done. Cooper had lost some teeth in earlier years that had been replaced with a permanent bridge, and on the first day of practice they were all capped and beautiful. After about the third scrimmage or so, all the caps were gone and only the studs were left, which embodied the way he played the game. At the end of the season he’d return to Breckenridge get the caps put back on and in returning to practice the next year, the process would start all over again.”

Cooper Jr. graduated with a Bachelor of Architectural Construction degree, but was not commissioned in the USAF due to poor vision. He entered the construction industry and was a cost estimator and superintendent during his career.

Cooper Jr married Batty O’Bannon in 1953. He was a loving father to their 2 daughters and 2 sons. Betty passed away in 1963. Cooper Jr met & married Sara Lynn Leck in 1964, and celebrated their 51st wedding anniversary on April 17, 2015. Coop & Sara lived in Odessa, Midland, Morgan’s Point Resort at Lake Belton, and College Station. They both enjoyed being active church members. Sara cheerfully organized family get-togethers for the holidays. Coop & Sara attended many class reunions, for Breckenridge High School, Wink High School, and A & M Class of ’53.

The signs of chronic traumatic encephalopathy are just now being discovered, so it’s difficult to know how his brain injuries contributed to how he lived his life. As a young widower with four children, Cooper Jr. was stoic in his grief, with quiet determination and a strong work ethic. If he had headaches, he did not complain. He did suffer with chronic sinus congestion and a runny nose. He was a perfectionist, both at home and at work as a construction cost estimator. His son Bill remembers hearing that Cooper Robbins was “legendary” and no one wanted to bid against him for a job, because he was so accurate, if you got the job, you had miscalculated.

In his life and work, Cooper Jr voiced his frustration with others’ dishonesty, incompetence or substandard work of any kind. During his 40’s & 50’s, his work-related frustration grew at times, into seething anger and insomnia. He was treated for depression. His competitive team spirit devolved into a kind of hateful, “you’re either with us or against us” outlook on life. Cooper Jr retired at the age of 70, and moved with his wife Sara to College Station. He planned to be active in the 12th Man Foundation, The TAMU Letterman’s Association, and the Aggie Class of ’53. He & Sara became active members of Covenant Presbyterian Church. They enjoyed road trips & weekend guests at their home. Unfortunately, he experienced more frequent episodes of angry outbursts, poor judgment, and worsening memory. He withdrew from social activities, and pushed away dear friends & family members as he became more reclusive. He disowned his children. He continued to attend church on Sundays, where he was cordial when greeting friends, but unable to carry on a conversation. He had always been controlling, but eventually, he would not allow his wife Sara (or their cat) to leave the house. He insisted on managing their finances alone, and yelled at her if she questioned him. He loved to work in the yard, but he suffered from peripheral neuropathy, and developed a stiff shuffling gait that could freeze up making it impossible to move. At 81, he began to have visual hallucinations and delusions, with cognitive fluctuations. He developed incontinence but refused help with changing his clothes. Most of the time, though, Cooper Jr. was still good natured and kind hearted, as if his childlike self was intact with good social skills, until he was angered again. Sara passed away in 2015, and Cooper Jr was moved to Assisted Living with his elderly cat Minnie at his side. He passed away on January 19, 2016.

Thankfully, Cooper Robbins Jr’s legacy donation and personal story may help improve awareness & education to prevent, or at least decrease the risk of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy in young athletes. In the words of his friend and teammate Walt Hill, “He was a great team player and was loved and respected by everyone privileged to be his friend. He was truly admired by and an inspiration to everyone with whom he came in contact and while he will be sorely missed by his friends, Cooper will never be forgotten.”