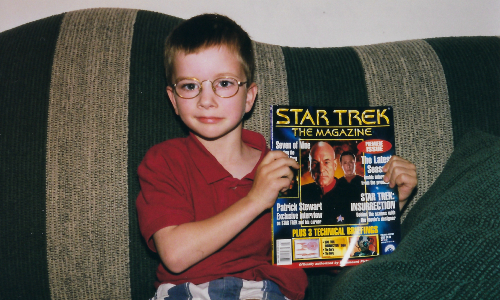

Nate Woodring

As a child, Nate was smart, happy, determined, motivated, always striving to be his best – and passionate about the things he loved. He could tell you everything about giant squids when he was five (“they have eyes the size of dinner plates”) and knew the story lines of every Star Trek Next Generation episode when he was in grade school. In fourth grade, he found his passion when he started playing drums with the school band.

Nate was a kid who never had to be told to practice. To the contrary, we had to ask him to stop playing the drums so he wouldn’t bother the neighbors, though we suspect they didn’t really mind hearing his music, especially as he got older. In high school, Nate was inspired by his band director to participate in the jazz program, which helped set the trajectory of his career path. Nate was a dedicated and talented musician, a deeply spiritual person, and an Eagle Scout. He was influenced by great jazz masters like John Coltrane to give his all with music. In his personal journal, he wrote, “I believe my music comes from a higher power.”

Nate went on to Michigan State University to major in jazz studies, and graduated in 2014. To all who knew him, Nate was a musician. He worked summers playing jazz at the Grand Hotel on Mackinac Island in Michigan for several summers, including the summer after he graduated. Shortly after, he earned a spot in a cruise ship band, and worked as a drummer in the Mediterranean for four months, coming home in March of 2015.

When Nate arrived at the airport upon returning from the cruise ship gig, the young man we welcomed home at the airport was not the Nate we knew. It was a testament to his internal will that he had even been able to navigate the trip home. He was nearly catatonic, had difficulty speaking or answering questions, and could barely eat or function. At the ER the next morning he was diagnosed with major depression with psychosis and spent ten days as an in-patient in psychiatric care.

Nate came home after his hospital stay, and during the following fourteen months, he and we did everything we could to help him with the tools we had. Bob changed the way he did his job and mostly stayed at home, to be with Nate and help in any way possible. While we were shocked and blindsided when Nate came home from the ship, in retrospect, we realize that his mental decline had begun earlier, as evidenced by what we thought was seasonal affective disorder each fall at college. His symptoms always appeared to go away shortly after onset, and didn’t seem cause for great concern.

For those diagnosed with depression, there are many methods for improving one’s state of mind including exercise, medications, and therapy. Nate doggedly tried them all, but nothing seemed to help. He was plagued by intense anxiety, memory loss, and what we realize now were symptoms of dementia. Along the way he became suicidal, and we eventually realized we couldn’t keep him safe at home. Three weeks before he died, Nate moved to a therapeutic farming community – a move we all felt was the best solution, given what we knew at the time. We still believe a therapeutic community is the right answer for many young people suffering from mental illness – but Nate never got better. Early on May 20, 2016, before sunrise, he ran out into a two-lane state route and was killed by an oncoming pickup truck.

As Nate’s parents, we did the things you do when you lose a child. We told his brothers, his sister-in-law, his grandparents and the rest of the family that he had taken his own life. We wrote an obituary, planned a funeral, began grieving, and tried to adjust to the new reality thrust upon us.

For Bob especially, the lack of explanation of a cause of Nate’s illness was a nagging presence, and he had accepted the reality that he might never have any answers. There was no history of mental illness in our families, and Nate’s severe symptoms were dramatic and unresponsive to treatment. There were three different diagnoses for his condition, every conceivable medication was tried, and nothing helped. There were many questions and no answers, either while he was alive or after.

We know now, three years later, that there is much more to Nate’s story.

Ever the sports fan, Bob read a Sports Illustrated article about Tyler Hilinski, the Washington State quarterback. It was difficult to get through the article because Bob knew the ending. Tyler had taken a hit in a game that changed his actions and personality, eventually ending in suicide. His parents had his brain analyzed and found that he had CTE. At that moment, Bob thought about Nate playing youth football from ages 11 through 14. Even though it seemed so long ago, Bob felt there could be a connection given the way Nate approached football, and everything else in life.

Bob immediately started a web search and found an article on the Concussion Legacy Foundation website about CTE. In that article he saw that repeated hits to the head before the age of 12 may make the brain less resilient to disease. The article also described symptoms of CTE, which include depression and problems with thinking. At that moment Bob realized that CTE symptoms may have been what Nate had been experiencing toward the end of his life. All of a sudden, we went from no answers to possibly every answer about Nate. In the proceeding days, Bob spoke with several medical professionals that all completely agreed with his conclusions.

Nate was one of the smaller kids on the team but he played with a lot of heart and determination. In 2004, at age 12 and in 7th grade, Nate received a trophy as the most improved player on the team. The coaches loved his intensity and the way he took on anyone, regardless of how big they were. He played linebacker and fullback on a primarily running team, which meant he was hitting someone on most every play.

Most Evanston Junior Wildkit Football players end up going on to play for Evanston Township High School. Nate played through his freshman year, age 14. He also played in the marching band which was an extension of his real passion: music. At the beginning of sophomore year, Nate had to choose between football and marching band and he chose the path of music – despite pleas from his coach to stay with football.

Nate excelled at his craft as one of the best drummers in the area. He became a great musician and jazz aficionado. Nate has inspired us to develop a love of jazz. We are proud of the way Nate approached life and are grateful to have found some sense out of a senseless situation.

We will never know for sure if Nate had CTE. We can’t be certain because his brain was not studied after death. But we suspect it based on Nate’s symptoms and other, similar cases. Former youth athletes have been diagnosed with CTE after death following exposure to head trauma at young ages. Athletes like Joseph Chernach, who was found to have Stage II CTE at age 25, and Kyle Raarup, who was found with Stage I CTE at age 20, are examples to consider alongside Tyler Hilinski.

As Nate’s parents, we bore witness to his struggle and we’re convinced that exposure to brain trauma at a young age, and subsequent CTE, caused his symptoms. Our conviction drives us to fight so that more people know the risks associated with exposure to brain trauma.

We hope to leave a legacy of helping others and we believe, for now, the best approach will be to attempt to convince parents that there is no reason to let their children play tackle football before the age of 14. The fact of the matter is kids don’t receive college scholarships in middle school, and exposing them to brain trauma at such a young age is not worth the risk. Given the popularity of football in this country it will not be easy, but we are up for the challenge. We did not have the knowledge of the consequences back in 2003, and we are ready to tell everyone Nate’s story. Our approach is simple. What do you love more – football or your child?

Suicide is preventable and help is available. If you are concerned that someone in your life may be suicidal, the five #BeThe1To steps are simple actions anyone can take to help someone in crisis. If you are struggling to cope and would like some emotional support, call the 988 Lifeline at 988 to connect with a trained counselor. It’s free, confidential, and available to everyone in the United States. You do not have to be suicidal to call.

Are you or someone you know struggling with lingering concussion symptoms? We support patients and families through the CLF HelpLine, providing personalized help to those struggling with the outcomes of brain injury. Submit your request today and a dedicated member of the Concussion Legacy Foundation team will be happy to assist you. Click here to support the CLF HelpLine.

Devon Wylie

Jay Wynkoop

Dennis Yanzick

Anthony Zahn

Anthony Cleverdon Zahn was born on October 14, 1974 in Riverside, California. He was diagnosed with a degenerative neuropathy called Charcot-Marie-Tooth (CMT) disease when he was 15 years old. CMT gradually reduced his strength and function in his lower legs and hands. Although CMT made walking, running, and most sports difficult for Anthony, he fell in love with cycling after reading about Greg LeMond’s 1989 Tour de France victory. Cycling was a perfect fit for someone with his condition, capitalizing on his aerobic ability while providing stability and security for his feet and ankles. In a sense, it gave him wings.

Anthony’s passion for cycling shaped much of his life from that time onward. He began competing in triathlon relays with friends and began going for long training rides and racing his bike on weekends. He worked in local bike shops, then opened his own shop — Anthony’s Cyclery — when he was just 22 years old. In addition to running the shop, he sponsored a competitive shop team, helping dozens of racers get their start in the sport.

Confronted with the progression of CMT and inspired by another paralympic cyclist, Anthony transitioned to paracycling competitions in 2005. He quickly rose within the paralympic ranks, representing the U.S. at international competitions and earning a spot on the 2008 paralympic team in Beijing, where he won a bronze medal in the time trial. Over the course of his career, Anthony also raced in Australia, Colombia, Mexico, Canada, France, Italy, Ireland, and Spain, winning a bronze medal at the Paracycling World Championships as well. He also competed at the London Paralympics in 2012, completing both the time trial and the road race.

Throughout Anthony’s cycling career, he suffered around a dozen concussions in crashes, losing consciousness in several instances. In the last 10 years of his life, he found it more difficult to keep focus and to read long passages. Nonetheless, his passion for cycling continued even beyond his competitive days. He loved working on his own bikes, but he also jumped at the chance to perform repairs on friends’ bikes. He also took up coaching, helping cyclists of all abilities — including his brother, Patrick — to meet their fitness or competition goals. In 2018, Anthony completed one of his own long-standing goals to climb Mt Haleakala in Maui — over 10,000 feet of climbing in one day — with his brother, Patrick, wife, Liz, and crucial support from Mom and Dad.

In August 2020, Anthony passed away just three months after being diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. Because of the likelihood that his accumulated head trauma might lead to CTE, before he passed he selflessly decided to donate his body to research in the hopes that his accidents and the resulting cognitive impairment might provide valuable data for other concussion sufferers.

Anthony was a staunch advocate for brain safety in all aspects of recreation, especially at the youth levels. He was well-read on the link between football and CTE and was an ardent opponent of youth tackle football. His family honors his Legacy by continuing to stress brain safety. Those who bike past members of the Zahn family without a helmet on will hear about it. One of Anthony’s worst crashes came from a short ride to the grocery store when he was not wearing a helmet.

Anthony met all of his challenges with courage and grace. He was a superb athlete who gave his all in every event he entered. He was an engaged and conscientious coach and a generous sponsor. He was loved dearly by his friends, family, and wife, Liz.

Roger Zatkoff

Larry Zeidel

Michael Zuga

Keep Your Eye on the Ball (and Your Brain)

Posted: November 16, 2015

A naturally verbose and upbeat man, Chuck inevitably began to speak with his neighbors. These lucky fans were in for a treat. They were sitting next to a legend, someone who had spent the last 182 days on the road and seen 223 baseball games at every major ballpark across the country. It was the second to last day of an epic trip that spanned the entire 2015 regular season. And the fans next to Chuck were probably debating whether or not to stay for the whole doubleheader.

Chuck’s baseball knowledge dwarfs even the most avid fans’, yet he doesn’t flaunt his acumen. He loves the game, and talks baseball for the sake of his passion. We’ve all spent a bus or plane ride trapped next to a chatty know-it-all, but that is never the experience with Chuck Booth. He is a pleasure to talk to and gives off a general aura of wellbeing and good intentions. But that hasn’t always been the case.

Chuck devoted his teenage years to the baseball diamond and football field. He threw himself into sports with the same passion that has carried him across the nation over the past year. However, his early athletic potential was jeopardized by a series of concussions both on and off the field that ultimately left him unable to play. All in all, Chuck recounts nine total concussions, one of which happened during an automobile accident in September of 2010.

Some of the symptoms from Chuck’s head traumas persist, although many have subsided or improved. He still battles dizzy spells, blurred vision, migraines, and sensitivity to light. However, these nuisances are a far cry from the man who once had to shut himself off from the world, a man that other people considered avoidant.

Chuck embarked on his journey across the country in part to recover from his most recent head trauma. With a dictate to take 6 months off from work, Chuck approached the problem proactively. He didn’t surrender into a concussed oblivion and let the symptoms rule him. Instead, he used the insurance settlement from his accident to tour the United States and do what he loves best: eat, breathe, and sleep baseball.

With a budget of just 100 dollars per game, Chuck made it work. His meager allowance proved sufficient for transportation, lodging, tickets, and food. Chuck attributes the daily grind of planning and putting one foot in front of the other as an essential factor in his progress. It has allowed him to reclaim his seat as the jovial fan that is a pleasure to be next to.

While on his admirable (and envy-inspiring) journey, Chuck helped promote awareness for his condition on behalf of the Concussion Legacy Foundation, which he selected as his charity designation. Chuck spoke candidly about his experience and why concussion awareness is so important in dozens of interviews that have appeared in newspapers, television, and online.

Chuck’s bitter history with brain injuries is one that many ex-athletes can identify with. But his tale of therapeutic recovery-via-baseball – like that rare MLB tripleheader – is rather unique.