Glen Ray Hines was a devout Christian, a loving husband, father, and an Arkansas football legend. He starred for the University of Arkansas from 1961-1965. Hines went on to play 115 consecutive games in the NFL for the Houston Oilers, New Orleans Saints, and Pittsburgh Steelers. After football, Hines began struggling with memory issues, became more reclusive, and suffered from severe depression. His symptoms only worsened before his death in February 2019 at age 75. His brain was later studied at the UNITE Brain Bank in Boston, where researchers diagnosed him with Stage 4 (of 4) Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE). His son Glen is sharing his story so others know his dad’s Legacy outside of football and CTE.

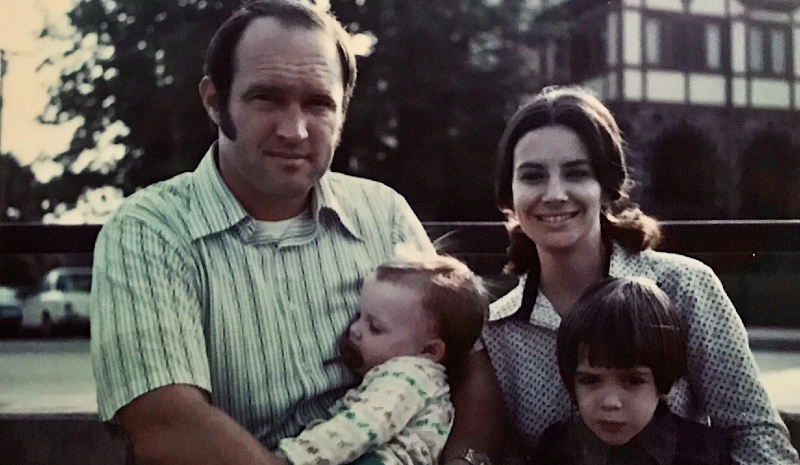

My father Glen Ray Hines was born October 26, 1943, in El Dorado, Arkansas. He graduated from El Dorado High School in 1961, and attended the University of Arkansas from 1961-1965. He and his family lived primarily in the Houston, Texas area, where myself, my brother Wes and sister Sheila were born, before he and our mother moved to the northwest Arkansas area.

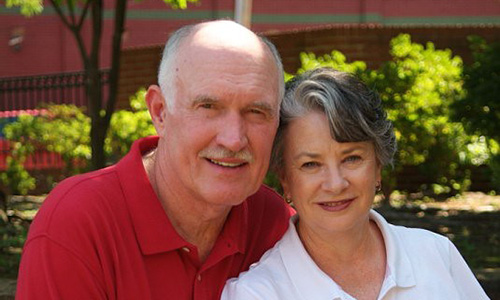

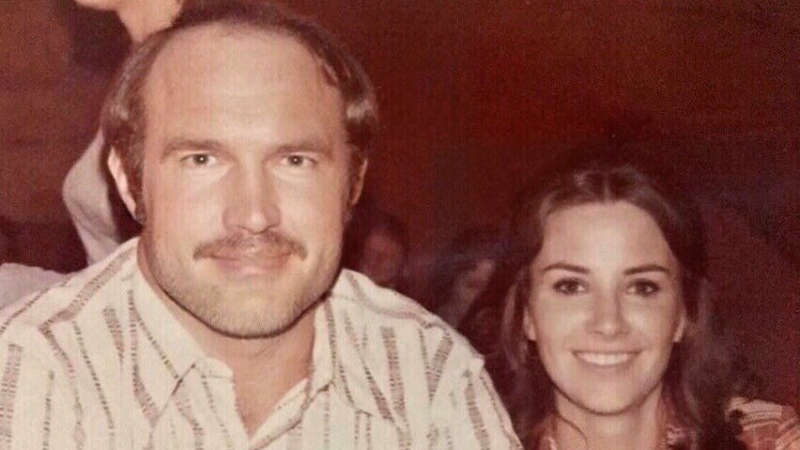

Above all things in his life, Dad loved his wife, children, and grandchildren. He met our mother Jody, his high school sweetheart, in their teens and they married in 1965. Dad was first and foremost a family man. He took an avid interest in his children’s education and extracurricular activities, but the event he was most proud of in our lives was our individual acceptance of Jesus Christ as our personal Lord and Savior.

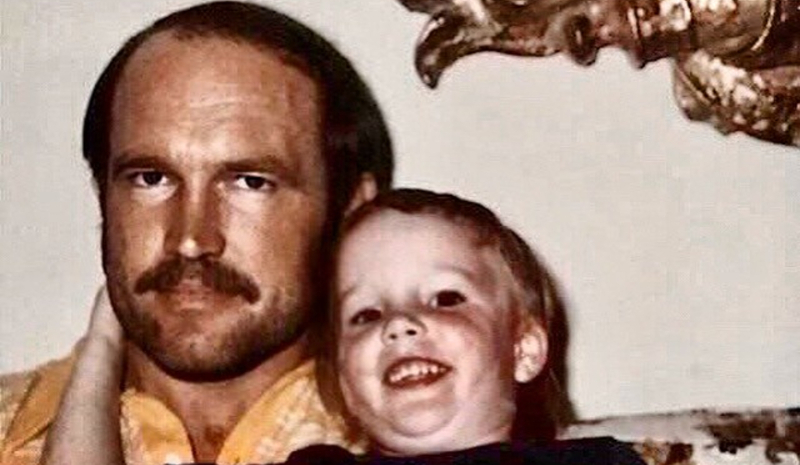

I’ve often told people that Dad was a big man, but he cast a very small shadow. He was a quiet man who preferred action over words. The most humble man his children ever knew, he would much rather speak with you about the latest accomplishments of his children or grandchildren than anything he had accomplished himself. I’ve never known another man to spend more time, quality and quantity, with his children. During our formative years, he was completely and totally invested in everything in our lives, and if you asked him, he – in a rare moment of being prideful – would tell you this investment paid off. After his children were grown with families of their own, he took a keen interest in his grandchildren’s lives, always asking about their education and activities, and in his later years, he enjoyed nothing more than attending their athletic and scholastic events.

Indeed, our father was his children’s hero, but not because of anything he did on an athletic field. That was a small, finite period of his life. He played football for only 15 years. He lived for another 60. It was what he did during the other 60 that mattered, at least to his family. It was what he did in those other 60 years that bore fruit. It was an investment that paid off.

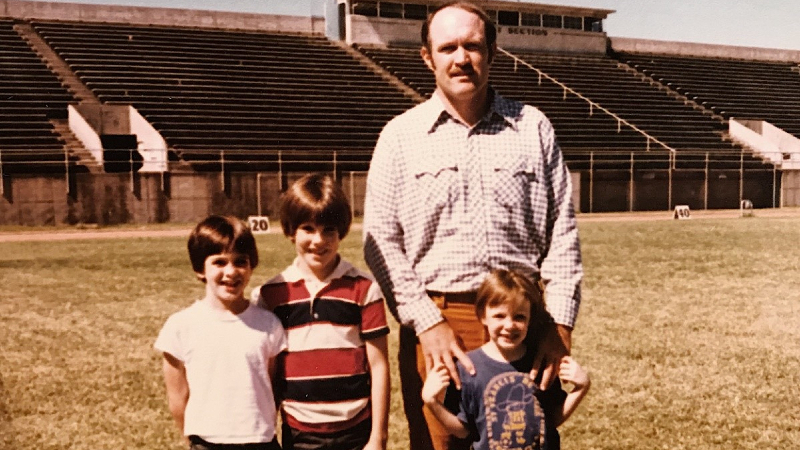

As much as I might want to overlook it, we must admit football was, without question, a significant part of his life. It affected his life as well as ours, in many different and conflicting ways. As much as football impacted his life, he in turn, left his own, influential mark on the history of Arkansas Razorback and Houston Oiler football.

A two-sport standout at El Dorado High School in Arkansas, he played collegiately for the University of Arkansas Razorbacks from 1961 to 1965. In 1964, he was the anchor of an offensive line that helped Arkansas win its only National Championship in football, and in 1965, he was a consensus All-American. The Houston Post named him the Southwest Conference’s Most Outstanding Player for the 1965 season, a rare honor for a lineman. In 1989, Dad was named as one of the best two offensive tackles of all-time in the 82-year history of the Southwest Conference when he was named a member of the Express News San Antonio, All-Time Southwest Conference Football First-Team Offense. In 1994, he was selected as a member of the Arkansas Razorback All-Century team. He was inducted into the Razorback Sports Hall of Honor in 2001 and the Union County (Arkansas) Sports Hall of Fame in 2012. In October 2018, he was inducted into the Southwest Conference (SWC) Sports Hall of Fame.

In 1965, there were two professional football leagues, the NFL and the AFL, and Dad was drafted by both; the NFL’s St. Louis Cardinals, and the AFL’s Houston Oilers. In 1966, he signed with the Oilers and played for Houston until 1970. He played the 1971-72 seasons with the New Orleans Saints, and retired after his final season with the Pittsburgh Steelers in 1973.

Dad was an accomplished pass blocker at a time when offensive linemen were severely restricted in the use of their hands to block pass rushers. He was an AFL All-Star game selection, the AFL version of the Pro Bowl, in 1968 and 1969. A model of durability, from his first season in 1966 through his final season in 1973, he started and played in 115 consecutive NFL games, including three playoff games. In December 2005, the Football Digest named him to the All-Time Houston Oilers Team.

But all this achievement and recognition that American society places so much value on, at least while football players are in the public eye, eventually came at a big price to my father and our family.

Shortly after he retired from the NFL in 1975 at the age of 32, Dad began to show some early symptoms that have become all too familiar to other football players and their families. When he was diagnosed many years later with serious neurological disease and probable Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE), these symptoms started to make sense in hindsight, but at the time our family had no idea what to make of them. He was reclusive. He was always writing things down in notebooks, which he had countless numbers of around the house that he would keep long after they were completely filled. We didn’t know why. He experienced sudden fits of anger that seemed to be way out of proportion to the precipitating cause. He would close himself off from people. He went through dark moods that made him unapproachable. He had difficulty maintaining a job, although he was offered numerous opportunities. His explanation at the time was that the jobs took too much time away from being able to spend time with his family. But we suspected there were other issues at play that made it very difficult for him to maintain steady employment. He avoided attending any functions that required him to speak publicly and did not often attend reunions of his football teams. People concluded he was aloof, standoffish, and even arrogant. But they had no idea what was really going on.

He also suffered from an acute, palpable depression that no one could understand, least of all him. It debilitated him, and in turn, it debilitated our family. Our fellow “football families” who have been through these same experiences can understand this and how this insidious affliction affects not only our loved one – our father, our brother, our son – who played the game, but it also leaves a wide path of damage in its wake that impacts everyone who loves and cares about them.

When it started to manifest itself, Dad even wrote letters to his children attempting to explain what he was going through.

“I can’t explain what exactly happened to me,” he wrote. “Lately I’ve been having more and more doubts of whether I will ever get back on track. It seems like nothing ever works out for me, though I still consider myself the luckiest man in the world and I have much guilt about letting myself get down after I have been blessed with so much in life. However, I haven’t given up, and I will continue to try and make something positive happen with my life. As long as I can breathe, I have a chance.”

He was still a relatively young man when he wrote this, but he knew there was something wrong. The real miracle of our father during these years was the fact that he was so strong, he was somehow able to hide much of this and keep it under control for the most part; to live with it while at the same time knowing he had some kind of strange affliction that he couldn’t understand. This is why during his last days, most of his friends expressed shock that he had taken such a rapid physical and mental crash that he was in hospice care within the span of about two weeks. No one had any idea how bad his condition was, nor how long it had existed.

Later in life, his physical and cognitive decline became more rapid and advanced, and he was eventually diagnosed with advanced dementia that his doctors found resulted from his football career. He decided to donate his brain for analysis to the Boston University CTE Center. Almost one year after his death, in January, 2020, the Boston University CTE Center diagnosed him with Stage 4 (of 4) CTE, the most advanced and severe form of CTE. There was “global spread” of the disease to every part of his brain and even in deeper parts of the brain rarely observed in other cases.

But football and his CTE diagnosis are not his legacy.

Despite what football did to him, he was still able to overcome it, until nearly the very end. With perseverance, he ran the race marked out for him, and he won.

His legacy is that he was an example. He was an outstanding role model for his children. He was the example of what a Christian husband should be. He was the example of a good Christian father and grandfather. He was the example of a humble Christian servant. And he was an example of a good and loyal friend.

This is the legacy he gifted us. And these are the things we will remember.

We are very thankful to the incredible staff at the Boston University CTE Center and the Concussion Legacy Foundation, especially Lisa McHale and Dr. Thor Stein, for their dedication and hard work, and the professionalism they exhibited from the first hours after Dad passed away through the long wait to find out the results of his testing.