Zack Langston was a talented football player at Pittsburgh State in Kansas. He chose the small Division II school over a larger Division I school so that he could be closer to his family and they could come to his games. As he went through college, Langston began to struggle with anxiety and extreme stress. After college, his symptoms got worse as the smallest things would stress him to the point of verbal self-assault. In 2014, Langston took his own life at the age of 26. His family donated his brain to research at the UNITE Brain Bank. Researchers at the Brain Bank determined Langston suffered from Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE).

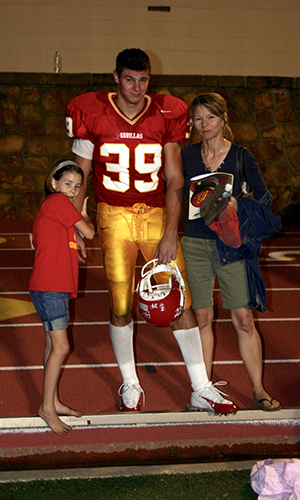

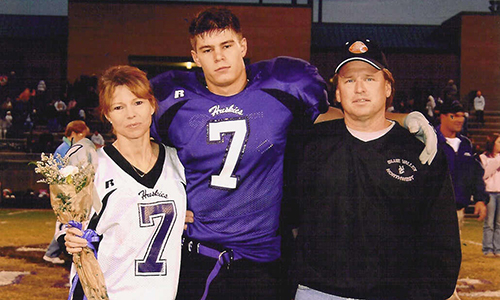

Zack played football at a Division II school in rural Kansas at Pittsburg State University. Though on the smaller side for a university, Pitt State was well known for being the winningest D2 football team in history. Zack was expected by many to attend a much larger university and play Division I football because he possessed the speed, size and athleticism of a top college football player. He chose however to attend Pitt State, only two hours from home after deciding he would have more fun on a team at which he would feel like “a big fish in a small pond” as opposed to just the opposite at a larger university. In addition, he wanted to attend a school at which his family would be able to make the drive to most of his games.

Zack was very happy with his decision to play football at Pitt State as he made many great friends, had a fun college experience, met the mother of his child and thoroughly enjoyed his football career. He never expressed regret over not attending and playing football at a larger university.

Toward the end of his college career we noticed Zack was beginning to struggle with anxiety and become stressed over small things. His father and I attributed most of his stressors to be caused by thoughts of having to soon leave football behind, getting a real job, and becoming a responsible adult.

Over time, after graduating from college his stressors seemed to be caused by the smallest of things like losing his car keys or being late for an appointment. He would verbally beat himself up, at least to his father and me, telling us how incompetent he was and how he couldn’t remember things, like making plans with friends and things people had told him in conversation. He was worried and embarrassed thinking his friends saw him as stupid. He began to get upset easily and punch holes in walls or throw things. As angry as he would get though, he never took his frustrations out on a living being.

Zack was always very compassionate, caring and kind hearted and his kind reputation stayed with him until he died.

Zack lost interest in socializing with friends, which was very unusual because before, spending time with friends was very important to him. He became extremely paranoid, thinking his friends and acquaintances were saying negative things about him at all times. He didn’t trust anyone anymore.

Zack confided in me that he was uncomfortable socially with everyone, even his father and me. Though he had been a somewhat quiet person naturally, feeling this uncomfortable and awkward socially was not Zack at all.

Whenever he was not working, Zack seemed to do nothing but sleep. He had almost completely lost interest in working out, which we had a very hard time understanding because he had always been a workout fanatic. His extremely healthy eating habits became a thing of the past. He began to lose weight as a result because he sometimes didn’t care to eat at all. Always an extremely muscular boy, beginning from about 8th grade on up, his muscular physique began to deteriorate.

Zack informed us that he was taking Adderall on a regular basis hoping it would help his memory; we were never sure if it really helped.

Within the last several months of his life, he confided in his girlfriend, Morgan, and myself that he was having suicidal thoughts. He had met with several therapists, attempting to find one who understood and could help with his struggles. He eventually gave up on therapy, feeling that no one seemed to understand how to help him; they all wanted to prescribe antidepressants which he was totally against. He checked into a psychiatric hospital and even gave in to his strong oppositions of anti-depressant use.

We knew he was desperate to get better and, as his parents, we made sure we were always available to him, day and night. At the slightest hint of frustration in his voice, we would drop everything and go to him hoping to talk him through whatever seemed to be his problem; sometimes what seemed like a very small problem to us, was extremely upsetting to him.

I spent a tremendous amount of time doing research, trying to find answers after he told me that he felt that “football messed up his brain.” Zack had even asked Morgan that in the event that he did take his own life, that he would like an autopsy performed on his brain.

Zack had discussed with Morgan the details of how he was planning to take his life. He was going to shoot himself in the chest in order to preserve his brain so that an autopsy could be performed to determine any damage that might have been caused by football.

Over a period of three months, Zack had purchased three guns. We managed to confiscate the first two guns from him. His dad began tracking his phone; we began looking for excuses to call him at work just to make sure he was there; then he bought a third gun. We didn’t get to him in time this time. His death happened just as he had described to Morgan — a shot to the chest.

At the time of Zack’s death, his son Drake was just barely two years old. Zack and Drake had a very loving relationship and were the best of buddies. Drake was the most important thing in Zack’s life. I feel that deep down, even though Zack had talked about suicide, I somehow didn’t believe he would actually take his own life because of his love for Drake. Drake is now four years old and continues to ask questions about why his daddy died and if he will ever see him again. Our explanation to Drake is that “daddy played football and his helmet didn’t do a very good job protecting his brain, so his brain was broken.” This is the hardest part of it all.

To be able to have some kind of closure with the diagnosis of CTE, has helped to some extent and I will be forever grateful to Boston University for the work they have done to help us acquire this closure. However, as Zack’s mother I continue to feel cheated not having knowledge of this horrific disease before it was too late. In our son’s case, we had no knowledge whatsoever of CTE until eight months after Zack passed away. I only hope that the results acquired in the study of Zack’s brain will bring much needed knowledge in how to protect athletes in the future and hopefully save some lives as well.

We love you and miss you so very much Zack, but we know that you are at peace now.

You are forever in our hearts and our family will never be the same without you, but we know that you are looking down on us every day and that gives us reason to smile. I believe you were always meant to be one of Gods angels. We know you will do amazing work. You are forever our baby boy. Mom and Dad.

Click here to read the Vice Sports article on Zack Langston