Daniel Brabham

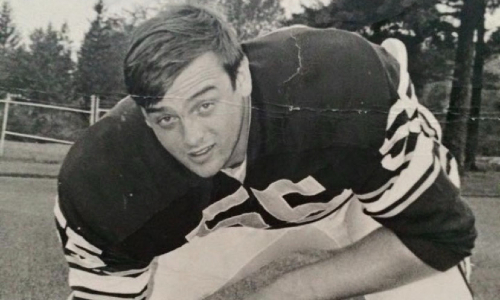

Daniel Brabham was an Air Force veteran, a teacher, a family man, an accomplished college and professional football player, and a lifelong crusader for change.

A former operator with Shell Chemical, native of Greensburg and resident of Prairieville, he passed away Sunday, January 23, 2011, in Baton Rouge, at the age of 69. He belonged to Carpenters Chapel United Methodist Church in Prairieville. He also formerly taught high school chemistry and math in Tangipahoa Parish. He was a veteran of the U.S. Air Force Reserves. He attended the University of Arkansas and LSU, receiving a bachelor’s degree in vocational agriculture and numerous academic recognitions through honor societies: Omicron Delta Phi, as well as being an Academic All-American.

He played football at college and professional levels, receiving distinction as an All-Southwest Conference recipient (1962) and as the third leading rusher in the SWC during his first year as a fullback. He was the first-round draft pick for the Houston Oilers and later traded to the Cincinnati Bengals, his career spanning from 1963-1968. He was a lifelong crusader for change, having smoking banned in his workplace in the 1980s and founding the Louisiana Fisherman’s Forum. He enjoyed genealogy (tracing his family history to Scotland and organizing reunions), handgrabbing for catfish (featured sportsman in Louisiana Conservationist and in a filmed documentary), aviation (acquired his pilot’s license), writing poetry and music, and spinning yarn surrounded by family and friends. Additionally, he was a steam locomotive and history buff, a self-taught player of the guitar and piano, and an avid reader.

William Buchanan

Jeffrey Burleson

William Burnett

Don Burt

Darryl Calvert

Joseph Campigotto

Have you ever tried to hold on to a runaway train? Just grab ahold and not let go even though you know where it’s headed? A year ago, I tried.

I got the call early Monday morning, April 25th. Angela, listen, she said, your dad stopped eating. It’s time to come home. I broke out in a rash. I couldn’t really breathe. I bought a plane ticket.

I knew it was coming. There was no avoiding that the years of slow decline would one day speed up and then it would just hit. Hit him. Hit all of us.

You think you are ready. For years I watched my funny, smart, creative, caring dad just drift away. I would catch glimpses of him every now and again. Even at his worst, I knew he was doing everything he could to protect me from what he knew was happening to him. We would talk as if it would someday just get better. We all know. It never got better.

I used to think…at least he is still here, if only physically. I can see him. I can call him, even if he really can’t say much back to me. He is still here. But as years went on, and it got worse and I could see just how much he was suffering, I knew he really didn’t want to be here anymore, my thoughts changed.

So many days I just wished he had cancer. I wished he had anything that would spare his mind, and just take his body instead. Maybe he will just have a heart attack. Maybe there is another way to make it end better, faster, for him…because we all knew how much worse it was going to get.

I never thought I would live on a planet where I would wish my dad a fast and unexpected death. But there I was. Wanting the man who I looked up and loved my whole life…to just die. It was so heartbreakingly painful. Absolutely devastating in every sense knowing there was nothing else I could do. That anyone could do.

I got to the nursing home and my dad’s bed had been moved to the corner. Now on a dramatic angle into the middle of the room. Walls bare. His favorite Pavarotti CD playing on the crappy little CD player we got for him. The plant I bought him still blooming in the window that faced a sad courtyard. Wearing his favorite Ohio State t-shirt, eyes closed, covered with a quilt, struggling to breath, turning grey, still looking so strong, still so much like a football player. He was surrounded by our amazing family and his loving and devoted friends. The hospice nurses administered morphine while everyone explained to me that he wasn’t in pain and the breathing sounded worse than it felt. He didn’t know what was happening.

I got there at 9pm. My brother at 11:30. Dad passed a little after midnight. We all held on to his body, sweaty and on fire with death. We all just hung on like we could stop it somehow. It did…it felt like jumping on the side of a train that was going over a cliff and you knew there were not brakes but you did it anyway. He took one last big breath. Opened his eyes to look around the room as if to confirm everyone he needed was there…and then he was gone. Just like that.

I still don’t know where I found the strength to be in that room. I would have placed all bets against myself to be able to stand there and just watch someone I loved more than anything disappear. But I had been watching him disappear for years.

Just slowly fading away, little by little with every phone call. Every visit there was a little bit less of him to visit. Every trip to the basement revealed more dust on his wood working tools. Slowly all his shoes replaced with Velcro. His shirts no longer had buttons. His vocabulary down to just a few words or sounds.

This is what football did to my dad, and my family. My dad was an all-state player. A really tough guy on all accounts. But he could not withstand this final blow from the sport.

My grandparents, Dee and Jim, are still alive. My grandpa just turned 90. My grandma in her 80s.

Angela, we just didn’t know. We didn’t know he could get hurt like this. Damn, I wish we would have known.

My grandpa and I suspected CTE as soon as dad’s symptoms became more pronounced. We would talk about it a lot. My dad’s doctors laughed me off the phone when I brought it up. Most didn’t even know he had played until I called and insisted it went into his chart. 7 years? No NFL? No way this is CTE.

But now we know. We know what my grandparents wish they would have known all those years ago. Every hit hurts. And in the end hurts more than just the player.

In a cab, on the way to the airport, I called the Boston University Brain Bank.

Hi there. My dad is going to die and I want you take his brain.

Not a call I thought I would ever make and not a call I want anyone else to feel like they need to make. The woman on the phone was sympathetic and thanked me. They moved swiftly to get me paperwork and had someone ready to take my dad’s brain the next day.

His brain went to Boston and where, just like in life, in death, my dad proved to be an exceptional case. With an unusual presentation, my dad’s brain is continuing to teach lessons to anyone who comes in contact with it.

So now, one year later, I have learned a lot about myself, my family, CTE, the amazing group of people working SO HARD at the Concussion Legacy Foundation (and I am SO happy to be helping them), and about how to live my life without my dad, who for so many years validated every decision I made.

Hey dad, you think I should buy a TV?

Well hell yes! Let’s go to Best Buy!

God damnit, I miss you dad.

I am who I am because you were who you were.

I will never stop working to stop this from happening to other players and their families. So buckle up people. We have a long ride ahead of us and we need some cash to make it happen. I kicked off a fundraiser Concussion Legacy Foundation and all the amazing work they do. My belief is the work they are doing today won’t only benefit those who have suffered repeated head injuries from contact sports, but also those who suffer from all types of degenerative brain diseases such as Alzheimer’s, which has touched so many of our lives.

Thanks for helping me remember my dad and thanks for helping to support the cause. Let’s stop this from happening to anyone else.

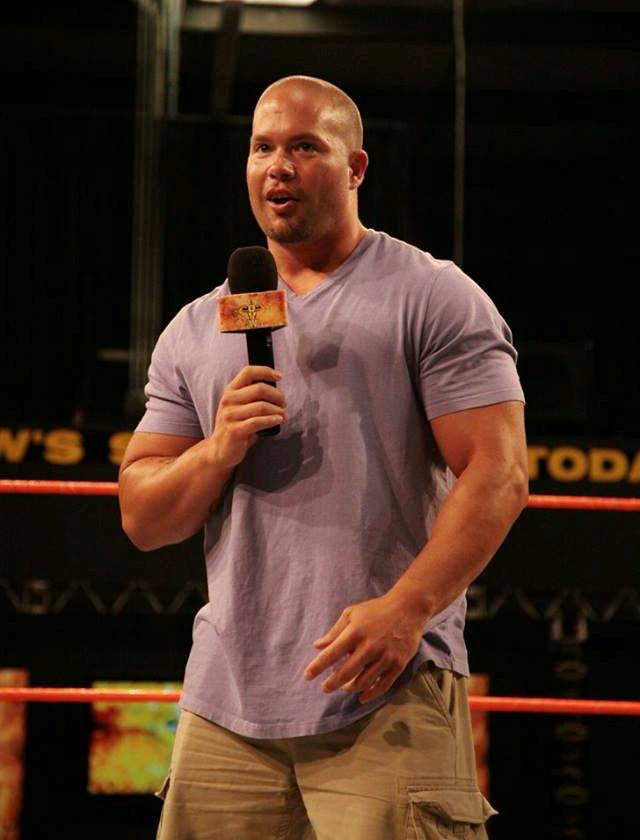

Matt Cappotelli

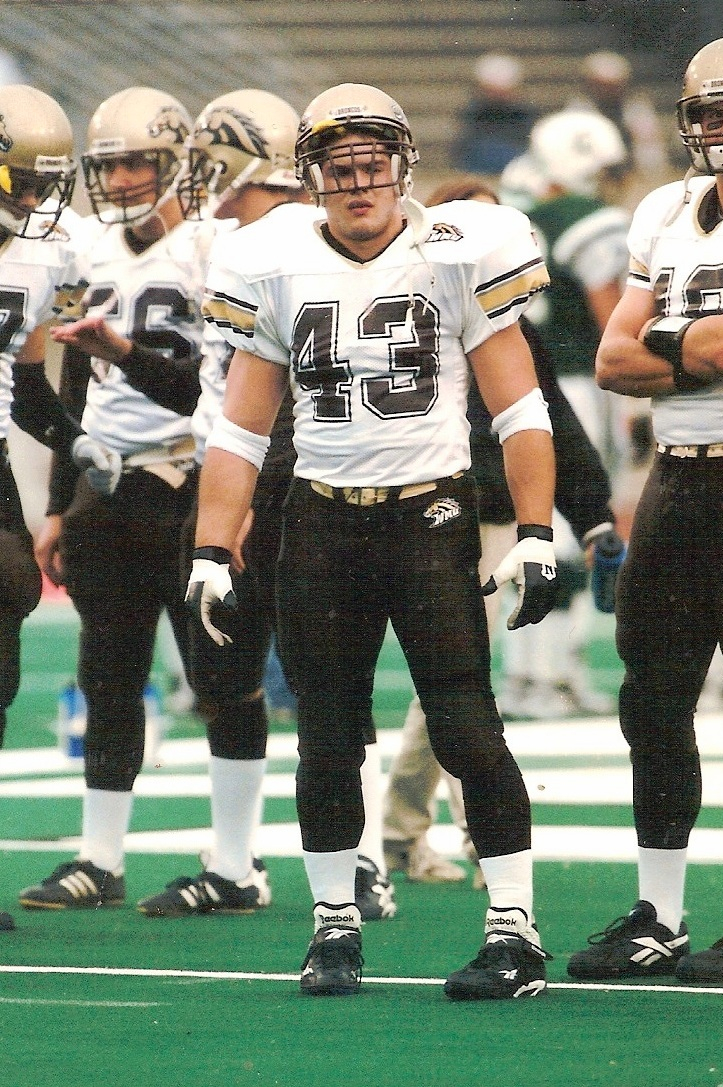

Matt grew up in the small town of Caledonia, New York, which was a huge football town. His dad owned a gym and had him start lifting weights at a young age, something he loved and continued for the rest of his life. He started playing football in 8th grade and quickly became a star player. Matt had a great work ethic and was an amazing athlete, but he was also smart, witty, funny, outgoing, humble, and kind. He was known in his town and high school not only as a terrific football player, but for his humility and caring personality. Matt was a Jesus follower, and you could see that in the way he loved and interacted with people.

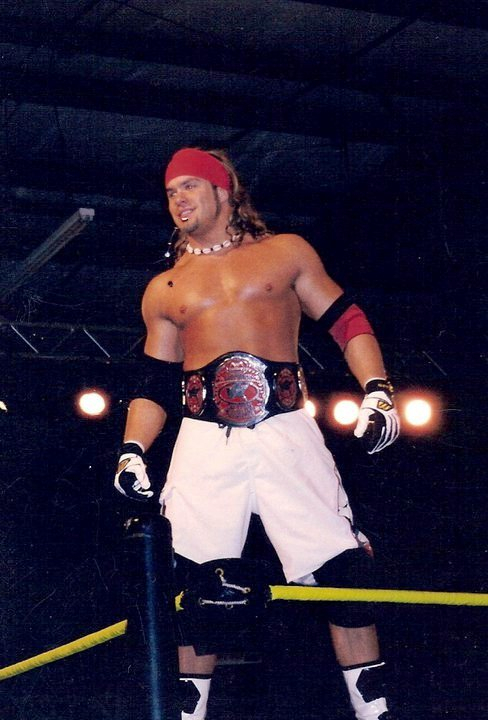

Matt continued playing football throughout his first couple of years of college at Western Michigan University, until he had to stop playing due to knee issues. This was when he decided to audition for Tough Enough, a reality show on MTV where contestants competed to win a contract with the WWE as a professional wrestler. Matt had been a wrestling fan since he was a little kid, growing up watching wrestling on TV with his dad. He ended up winning the show and was then sent to Louisville, Kentucky, to train at Ohio Valley Wrestling before being put on TV. That’s when I entered the picture.

Ohio Valley Wrestling (OVW) held a live weekly show on Wednesday nights that I would occasionally go to with friends, and we ended up meeting there after one of the shows. I knew who he was from watching Tough Enough a few times, and I was instantly drawn to him because of his strong faith. After our first date, I knew he was “the one” and that I would marry him some day.

We dated for two years, during which he continued to train at OVW, as well as occasionally travel to shows with the WWE. Matt’s dream was to become a WWE Superstar, not only because he loved to entertain and perform, but also to be a positive example for Christ in that industry. He was on the verge of his dream becoming reality when he discovered he had a brain tumor. It was one week before he was set to debut on Monday Night Raw.

Incredibly, Matt had no symptoms and only discovered the tumor after being knocked unconscious in the ring during an OVW match. He was sent to the hospital to get checked out, which was when they discovered the tumor. After a biopsy, Matt was diagnosed with stage 2 brain cancer. We got married on the beach in Hawaii two months later.

Unfortunately, with the cancer diagnosis, Matt had to put his dream of becoming a WWE Superstar on hold. In 2007, he had surgery to remove the tumor, and then did six weeks of proton radiation, followed by oral chemotherapy for the following two years. From that point on, he had MRIs regularly and the scans were clear for the next 10 years.

We had an amazing 12-year marriage, and I’m so thankful for those cancer free years I got to have with him, living life to the fullest. From our beach trips, to cruising in the Jeep on summer nights, our pizza and putt-putt dates, and even just our boring nights chilling on the couch at home, every day with him was fun. His smile and laugh were the joy of my days. I thanked God every single day for sending him to me. I never imagined the tumor would come back and naively thought his fight with cancer was over. Little did I know; the worst was yet to come.

Exactly 10 years after his first brain surgery, an MRI showed the tumor had grown back. I’ll never forget the day I got that call and heard those words come from his mouth – my worst nightmare had come true. Two days later, Matt had surgery to remove as much of the tumor as they could from his brain. About a week later we got the official diagnoses: Grade IV glioblastoma multiforme (GBM), the worst and deadliest form of brain cancer. The prognosis for GBM is not good, and we were told that even with treatment, the average life expectancy is around six months.

Matt underwent chemotherapy and also used a device called Optune, a fairly new form of treatment for brain cancer. Unfortunately, the treatments couldn’t keep the tumor from growing, and he continued to decline as the months went by. Watching my strong, outgoing, energetic husband slowly deteriorate was the worst thing I’ve ever been through in my life. He passed away exactly a year after his brain surgery on June 29th, 2018.

I knew Matt wanted to donate his organs, but because of the cancer he was unable to do so. He couldn’t speak towards the end, but I just knew he would have wanted to do something to help others in some way. Then I remembered his interest in CTE. During Matt’s time with the WWE, he became friends with Chris Nowinski and learned of the work he was doing to advance concussion and CTE research.

Matt was committed to CTE research as someone who had suffered multiple concussions in the past through football and wrestling, and someone who always wanted to help out a friend in any way he could. When he had his tumor removed in 2007, he reached out to Chris and coordinated sending the brain sample to Boston and the UNITE Brain Bank, just in case they could learn something from some of the healthy tissue that was removed. He did the same thing after his surgery in 2017. When we lost Matt, I knew he would have wanted his brain donated to help further CTE research. So that is what we did. He is the first person to have his brain tissue studied for CTE while he was alive and after he passed away.

While Matt had no obvious symptoms of CTE I saw during his life, it’s hard to really know because of the enormous changes his cancer caused. He did suffer from mild seizures or partial seizures, as they’re called, for the last two years of his life. Around the same time, he was also diagnosed with Parkinsonism, which is a neurological disorder that has many similar symptoms of Parkinson’s disease, such as slow movement, speech and writing changes, and muscle stiffness, among others. I noticed some of these changes a few years before he died, as well as some slight personality changes over the last few years.

When we got the results back from the donation, we learned he had been diagnosed with CTE, as well as Parkinson’s Disease. I found myself a bit emotional after hearing the diagnosis, and it explained a few things for me. Now I know that along with everything he dealt with from his brain cancer, he may also have been experiencing the early stages of CTE’s effect on his mood, memory, and thinking. Despite all of this adversity, he handled it like a champ, always stayed positive, and never complained.

The most common thing people say about Matt is that he was one of, if not the BEST, person they knew. He impacted countless lives. There was something about him – his smile, his laugh, just his presence, that drew people to him. More than that though, I think it’s because of the way he genuinely cared about others and how he made everyone he met feel important, no matter who they were. He made everybody feel like a somebody. He loved helping others and making people laugh. I think he was happiest when he was putting a smile on someone else’s face.

Throughout all of his injuries and health conditions, and even after two brain surgeries, chemo, and radiation, he never complained or felt sorry for himself. He never let it get him down. He was still always looking out for others and always laughing and joking around, even at the very end of his life. That was just Matt. I know he was disappointed that his dreams of becoming a WWE superstar didn’t become a reality, but he didn’t let it get him down. He continued to trust God’s plan and made the best of where He put him. He continued to help and inspire others, even if it wasn’t in the wrestling ring. All he wanted to do from his initial diagnosis of brain cancer in 2006 was to help and inspire others with his story and to point them to Jesus, and my hope is that his story will continue to do so. I’m thankful for the Concussion Legacy Foundation and that Matt was able to play a role in advancing the research and awareness of CTE, which I know is what he would have wanted.

Carey Jr. Herbert W.

My father was one of the greatest men to ever live. He was thoughtful, kind, caring, hilarious and above all, loved his family more than life itself. Dad was my hero.

My father, Herb Carey Jr., was born on February 12, 1951, in Salem, MA and was raised in Marblehead, MA. My dad was born into a football family. My grandfather, Herb Carey, Sr. was captain of the 1950 Dartmouth College football team and was drafted by the Philadelphia Eagles, though he decided not to play professionally. Ironically, my grandfather died of a brain tumor in 1983, but I often wonder what story his brain would’ve told.

From the time my father was a young boy he played football and absolutely loved the game. Dad played throughout middle school and high school, and also played all four years of his college career at the University of Maine, Orono. Throughout most of those years, my mother, Linda Hardwick Carey, was on the sidelines cheering him on.

My parents met when they were in middle school. They were married in June of 1972, the year before my father received his master’s degree. They would go on to spend 48 years of marriage together, raising two daughters and five granddaughters. But their marriage wasn’t always easy.

From the time I can remember, my father abused alcohol. Dad wasn’t aggressive, or mean, but he drank every day, and sometimes, all day. He received a few DUIs and lost his license for a period of time. I recall begging him not to drink before he came to any of my field hockey games, track meets, or before any major event, such as my prom, or family weddings. My dad finally got sober in July of 2004, three months prior to my wedding.

In addition to his battle with alcoholism, my father made some poor choices throughout the years. Dad had a temper, ironically, when he wasn’t drinking. Every once in a while he’d display erratic behavior, which became more frequent towards the end of his life.

One day, in the spring of 2012, my father was outside with my two daughters and he couldn’t recall their names. One of them is Carey, my maiden name, and the other is Hagan, his mother’s maiden name. It scared him, and it scared us, so we sought help.

In July of the same year, when my father was 60 years old, we received the punch in the gut of a lifetime: an Alzheimer’s Disease diagnosis (after his death, we learned my father had stage 4 CTE). I vividly remember that day. After the appointment, I recall getting in my car, trying to process what I had just learned and wanting to throw up. The news hit me like a ton of bricks, and I had so many questions. How long would my dad live? What would his quality of life be? How would my mother handle this? How would I handle this? After all, he was my best friend. I also wondered how this happened since we don’t have a family history of Alzheimer’s. So, I couldn’t help but immediately think of the years he’d played football.

When you’re diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, you’re diagnosed with a death sentence. There has never been an Alzheimer’s survivor, and the journey for both the patient and their loved ones is the most grueling, heart-wrenching, painful experience. We know this now, because we’ve lived it. Alzheimer’s isn’t just about “forgetting” things; Alzheimer’s for us, was having to tell my dad he couldn’t work any longer and needed to retire. Then came the time we had to tell him he could no longer drive, or when we had to convince him to downsize and move out of their house because we knew it would help my mom. There was also the gut-wrenching decision of having to remove him from my parents’ home, because it wasn’t safe for my mother to be with him any longer. This wasn’t my dad; it was Alzheimer’s. I don’t wish this on anyone, and my father didn’t either. In fact, he offered to sign up for as many trials and studies at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) as humanly possible. He always said, “I know it won’t help me, but if I can be a part of something bigger, or a part of a cure so that another family doesn’t have to go through what we’re going through, then I’ll do it.”

My sister and I took turns driving my dad to and from MGH for years for him to participate in trials. I grew to love those trips to and from Boston because I was able to spend more time with him. I’ll never forget the last day of the last trial he was eligible for; the trial was over, and my father’s Alzheimer’s had progressed to a point where he was no longer eligible for trials. I remember telling him we were leaving the hospital and he asked me where his medication was (it was always handed to us in a brown paper bag). I said, “Dad, the trial is over, we don’t have any more to participate in.” He collapsed into a chair and started crying. He said, “I need the trial medication, I need to do this for your mother, I need to be here for her.” I sat next to him, we had a good cry, and I told him things would be OK.

In 2016, he told us he had made the decision to donate his brain to the UNITE Brain Bank at Boston University upon his death. My dad wanted to do whatever he could to help others, but that was Herb Carey. Dad had a heart of gold. My father showed up for everyone, especially for his wife, two daughters, and five granddaughters.

In March of 2020, just as the world was shutting down, so was my father. We had to remove him from my parents’ home (for my mother’s safety) and find a place for him to live. Little did we know at the time it would be months before we’d be able to see him or hug him again. When we were finally able to reunite, we could see the decline.

On March 21, 2021, my dad lost his battle with Alzheimer’s. We donated his brain to the UNITE Brain Bank at Boston University upon his death and in January of 2022, our suspicions became reality. Dr. Ann McKee diagnosed my father with stage 4 (of 4) CTE.

In the end, the sport that my father loved, didn’t love him back. Instead, it cost him his life. Our hope is that with his brain donation to the Concussion Legacy Foundation, they will continue their tremendous efforts, so that one day, the world will be free of CTE.