Joseph Casarsa

Joseph Coffey

Bo Cothran

Louis Creekmur

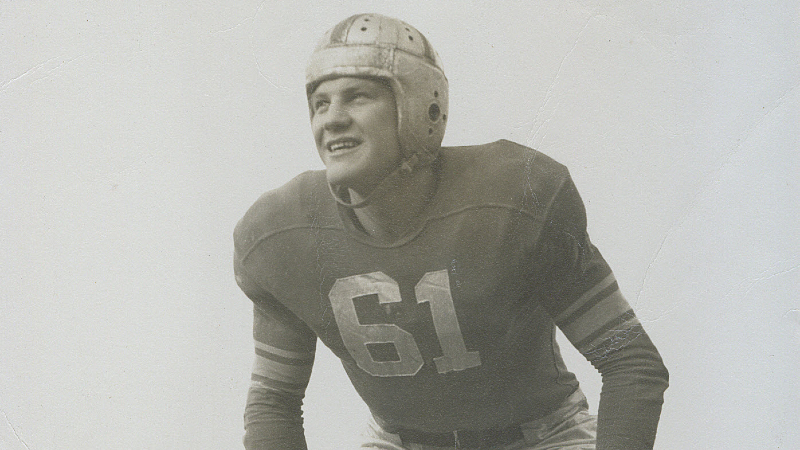

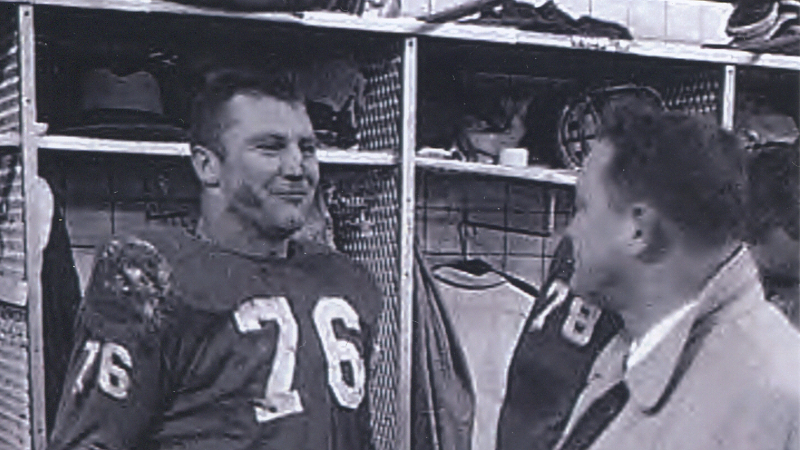

Lou Creekmur was unwaveringly loyal and relentlessly tough in everything he did. Creekmur was born on January 22, 1927, in Hopelawn, New Jersey. He went on to play college football at the College of William and Mary, but his football career was interrupted when he served in the US Army to fight in World War II in 1945 and 1946.

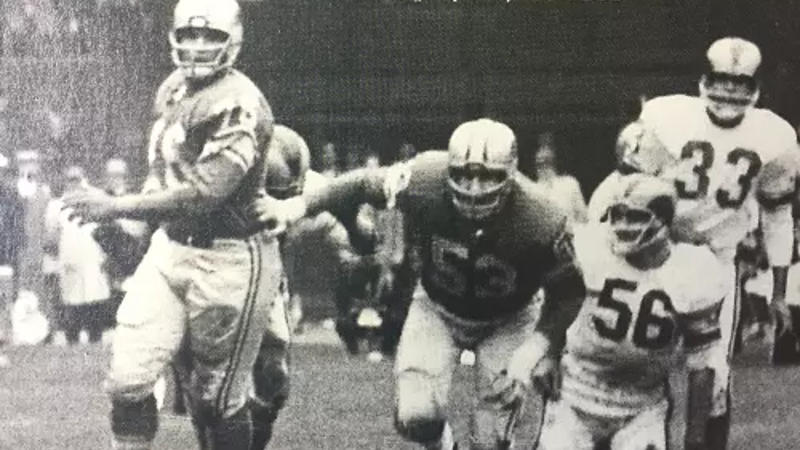

Creekmur returned to William & Mary and finished school before being acquired by the Detroit Lions prior to the 1950 NFL season. He immediately held the crucial responsibility of protecting Bobby Layne and Doak Walker, the Lions’ star quarterback and running back, respectively. Early in his first season, Creekmur felt Layne’s scorn after allowing a sack. He made a vow to his quarterback.

“I didn’t want to take the wrath of Bobby Layne. If I was going to stay in the league, I was going to block for Bobby Layne. I was going to do everything possible to not let any one of those defensive guys get to Bobby Layne,” said Creekmur in an NFL Films documentary.

He lived up to his word. Creekmur played every single snap in every practice, and all 165 preseason, regular season, and playoff game the Lions played from 1950-1958, including NFL Championship games. In many of those games, Creekmur was playing with at least one significant injury.

“I played one complete season with a crushed sternum and just put a pad over it… You were going to get paid on Monday, so I had to play on Sunday,” said Creekmur.

In addition to his litany of bone and muscle injuries, Creekmur also suffered several concussions in an era where offensive linemen led with their heads, not their hands. He and his last wife Caroline recounted “16 or 17” concussions in his career.

During Creekmur’s career, playing in the NFL wasn’t all that lucrative. He, like many of his peers, held day jobs during the football season. Creekmur was a manager at the Saginaw Transfer Co.

“There were many days when I’d make a call on a Monday morning after a football game with a black eye or a bloody nose or a cut across my forehead. For some reason, I was always let in to see the boss first,” said Creekmur.

After the 1958 season, Creekmur retired from football to focus on his business career. But after the Lions started out with a dismal 0-4 record in 1959, Creekmur’s iconic loyalty was on full display. The Lions called him back to play, and Creekmur obliged to help the Lions finish out the season. He officially retired from football after the 1959 season.

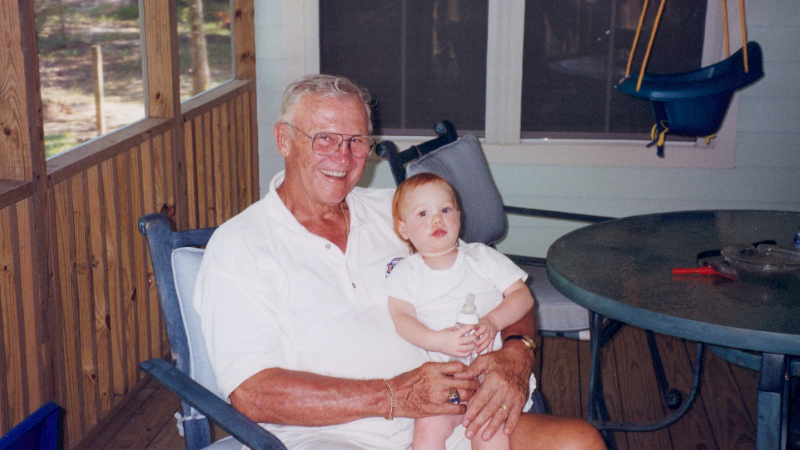

In 1996, Creekmur’s tenacious nature paid off once again. After years of urging, Creekmur was enshrined in the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

Creekmur went on to serve as the Public Relations Director of Ryder Systems, Inc. until his retirement. But in the late 1970’s, Creekmur began to experience cognitive and behavioral issues. His memory progressively faded, he grew inattentive, his executive functioning declined, and he became increasingly intense, angry, and aggressive. He was thought to be suffering from Alzheimer’s disease.

Lou Creekmur passed away on July 5, 2009, at age 82. After his death, his brain was studied by Dr. Ann McKee and the research team at the UNITE Brain Bank. He became the 10th former NFL player diagnosed with Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE).

“By examining his brain, I was able to confirm that there was absolutely no sign of Alzheimer’s disease or any other type of neurodegenerative disease except for severe CTE. This is the most advanced case of CTE I’ve seen in a football player; his brain changes were similar to those of profoundly affected professional boxers,” said Dr. McKee in 2009.

Creekmur’s brain pathology helped show the world the toll a career in football could have. He will forever be known for his relentless offensive line play and his dedication to his country, his teammates, and his family.

Jim Crenshaw

Jim Crenshaw grew up in Weir, Mississippi, where Friday night lights were the weekly highlight for the entire town. He began playing football in middle school, continuing for 10 years and suffering multiple untreated concussions. He received a scholarship to play for Mississippi State where he played for one season, but when Jim’s coach moved to University of Richmond, Jim followed. There, Jim was co-captain of the football team, played in the 1968 Tangerine Bowl, and holds the record for most punt returns in a game. His primary position throughout football was running back.

I met Jim in 1991. We were friends for a couple years before we became a couple. He was charismatic, funny, and so very handsome. What attracted me most was his strong faith. He believed completely in God’s faithfulness and grace which was what got all of us through this long journey.

Jim never met a stranger and could strike up a conversation with a tree. That is probably why he enjoyed such a successful career in medical sales. I knew he was disorganized and that he often forgot things but I thought that was “just Jim” and it did not at that time interfere with his success or relationships.

We married in 1996 and began what I thought would continue to be a life filled with travel, laughs, and new memories. We both loved football so autumn weekends were our favorite and bowl season was a traveling frenzy. Within a couple years I saw Jim’s struggles more closely—how he had to work so hard to remember appointments, to get places on time, and the extra time he put in his work to get it all done. I noticed erratic sleep patterns and some nights of almost no sleep at all.

We talked about his sleep issues and decided they had to be due to stress. Jim agreed to see a psychologist who diagnosed him with ADHD and his family physician prescribed an anti-depressant for anxiety. This helped but it was certainly not a cure. It thankfully allowed Jim to manage his symptoms. Sleep came more easily, but he still never slept more than five hours per night. He lived by sticky notes and his calendar.

The years moved on and Jim’s personality changed slowly. His methods of compensating were no longer working so his symptoms became more obvious. He was more emotional and frustrated. There was more memory loss. The man who could talk to a tree now struggled to carry on a comprehensible conversation. I was so frustrated at this point because I had no clue what was happening to my husband. In hindsight, I didn’t know how good it would have been if Jim’s symptoms plateaued there. But it got worse.

Jim forgot bills had to be paid but continued making purchases and nearly drained our finances. His financial mismanagement was the biggest red flag of all. At his best, Jim was the most frugal man on Earth! He lost important papers. He got traffic tickets. He got lost in the most familiar places. He would sneak out at night. He hoarded everything from toilet paper to newspapers to water. He was not being productive at work, so he was asked to take early retirement, which was very kind of his employer. They could have let him go with no compensation.

Jim saw a neurologist, internist, cardiologist and family physician. In a twist of irony, the internist referred us to the psychologist that had seen him 15 years earlier. No one could give us a diagnosis. The neurologist offered early Alzheimer’s Disease which I immediately rebuked. This just did not look like the typical Alzheimer’s symptoms. But the neurologist had no other guess.

From there, life became a blur. Jim took a nosedive into the deeper symptoms of CTE and by 2013 I truly thought I was going crazy. We had sold our home in Atlanta and moved to Florida to be near our daughter who is a nurse. I needed a support system. Our new primary care physician there recommended a neurologist in the area and we had our first appointment with him in July 2014. He spent five minutes with Jim and said, “It is CTE.” I said, “What is CTE?” He proceeded to tell me. At that point it did not matter that he said there was no cure. I finally had a promising suspected diagnosis we could confirm after death. There was a reason my husband was having these problems. He was not choosing to be a different person. He did not want to be like this. He did not want to make my life difficult. He was the same person I married except now, his brain was so sick it was affecting every other part of him.

Jim passed away on January 18, 2019, at age 71. His brain was sent to the UNITE Brain Bank. Researchers there confirmed our suspicions. Jim was diagnosed with Stage 3 (of 4) CTE.

From 2014 until Jim’s death, I watched that sweet, fun, lover of mine stop talking, walking, and eating. I watched him turn into something no one should ever have to become. CTE took so many good years of his life and the lives of our family. It took away a fun grandfather of 13 and stole years of unmade memories. It took his dignity. It took his arms, legs, and organs. But it could not take the legacy Jim Crenshaw leaves behind for his family and friends, and all the people he met along his journey — those “trees” he talked with who probably did not even know his name. Thank you, #42. You are loved and missed!

Daniel Cullinan

Joe Curry

Stephen Cushing

Willie Daniel

Willie Daniel’s pro football career eventually cost him his memory, but it also brought a good life for his family. The former NFL player, a Mississippi native, died at his home after a lengthy illness surrounded by his loving family and devoted friends.

Willie was born on November 10, 1937, in New Albany, MS. He grew up in Macon, MS, where he lettered in basketball, track, baseball, and football at Macon High School all four years. He received a scholarship to Mississippi State University where he lettered in track and football for four years before graduating in 1959.

His professional career took an unexpected turn, said wife Ruth. “Willie wasn’t drafted out of college and was hired as an assistant football and head track coach in Cleveland, MS. He received wide publicity when an irate parent became physical with him because the coach didn’t play his son in a game. When approached by the Steelers to turn pro, he quickly changed his mind about being a coach, joking that “Pro-ball wouldn’t be any rougher than this.”

Willie became a nationally known sports figure in the 1960s as a result of a stellar football career which began at Macon Mississippi High School and continued though Mississippi State University. His professional career took off quickly and he spent nine years with the National Football League where he gained a reputation as a speedy defensive back. The Pittsburgh newspapers listed him as one of the prize rookies of the year in 1961. In 1986 he was inducted into the Mississippi State Sports Hall of Fame. He spent six years with the Pittsburg Steelers and three years with the Los Angeles Rams until a knee injury forced him to retire in 1969.

He returned to Starkville, Mississippi, and became a partner in a very successful general insurance agency. Willie also recognized that the fitness industry was about to explode and he saw an opportunity to become one of the pioneers in the operation of health clubs which have remained a national obsession. He opened the Willie Daniel Athletic Club in 1970 and offered weights, aerobics, massage therapy, sauna, steam baths, karate, and a nursery for children. In 1975 he built the first of two racquetball courts which led to the formation of the Mississippi Racquetball Association.

Somehow Willie found the time to give back to his community. He coached and sponsored Starkville junior baseball teams as well as the Starkville Open Football League. He served as chairman of the annual Oktibbeha County Cancer Crusade which became the first county in Mississippi to triple its annual contribution quota. He was a member of the Mississippi State “M” Club, Bulldog Club, “Old Dawgs” Club, and the National Football League Players Association. He was a member of the First United Methodist Church in Starkville, the Fellowship of Christian Athletes, and the Savage Bible Class where he served as President. He was one of the original members of the Starkville Kiwanis Club, and the Starkville Country Club where he made the club’s first “hole-in-one” in 1975.

Willie and his wife, Ruth, raised three children, Sandra (husband Jeff), Kent (wife Evalin), and Richard. They have four grandchildren and one great grandchild. Life was busy, but good—as one of the neighbors used to say, “When I grow up, I want to be Willie Daniel!”

By the time the clock registered the new millennium, Willie was facing the most monumental challenge of his lifetime when his mental health began to deteriorate. Actually, his mental health had begun to deteriorate in the 1980s but he was able to work until 2001. This downward spiral into the world of dementia was attributed to the numerous concussions he suffered during his football career.

Willie became very frustrated, angry, and sad. He lost his short-term memory, couldn’t even remember his birthdate or the birthdates and ages of his children and grandchildren. One very traumatic event for him was the day his family had to take his truck keys and remove his truck. He would actually cry and beg to get his truck back. He never could understand why he couldn’t drive and this became a daily verbal confrontation.

By 2009, he was becoming more and more combative. He never actually hit anyone, but he was threatening to his wife and his caregivers. His family made the agonizing decision to move him to an Alzheimer’s facility. He lived there for a year, but then had to be moved to a full care nursing facility. For the last six years of Willie’s life, he was incontinent, could not sit up, had very little movement in his arms or legs, and hadn’t spoken in six years. He was moved from his bed to his wheelchair with a lift, and was tube fed.

The road that Willie and his family traveled over these past several years has been difficult to say the least. But as Ruth says, “My heartbreak is nothing compared to what Willie has faced. He loved his God, his family, his life, his friends, his church with all his heart. He lost that all far too soon.”

Willie qualified for and became a part of a state-of-the-art research project at Boston University being conducted on football head injuries. He donated a portion of his brain and spinal cord for the research project in hopes of developing procedures and equipment to make the sport safer for athletes of the future.