Brian Fronczek

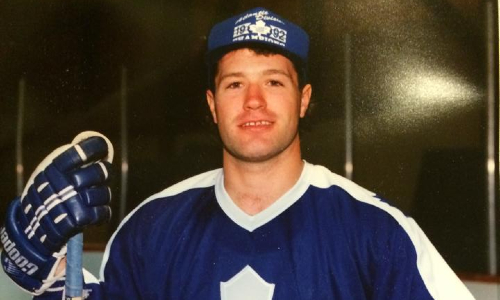

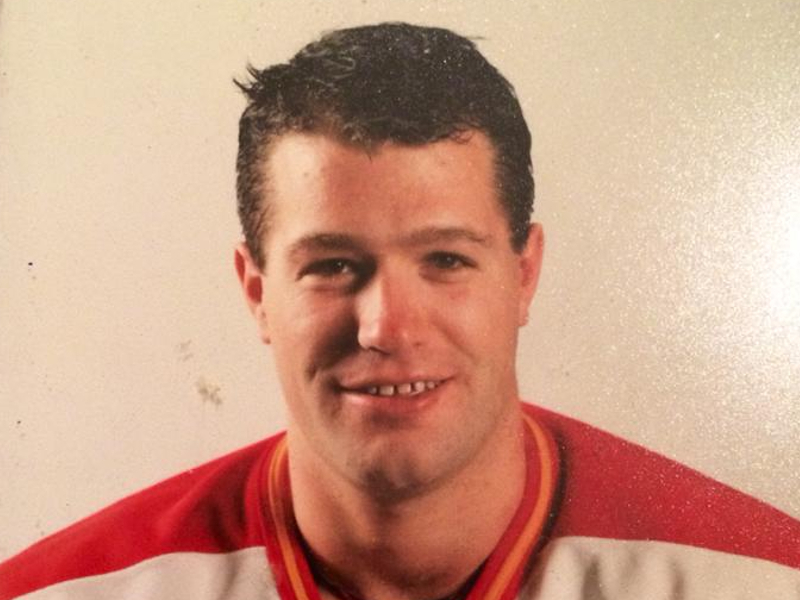

Todd Gillingham

Todd Gillingham had a quirky smile and a twinkle in his eye. He was the guy who lit up a room when he walked in. Todd was the life of a party and knew how to live each day to its fullest.

Growing up in Corner Brook, Newfoundland, Canada, Todd spent the summers of his youth on the baseball field, with cleats and bats giving way to skates and sticks during the winter months. He excelled at both sports but eventually turned his full attention to hockey, which he started playing around four years old. He was always the biggest guy on most teams, so expectations for him to excel were always high. But no problem for Todd — he surpassed them and much more.

Though Todd was big and could throw a hit, he would often give a shoutout to the smaller players prior to checking them. That’s the kind of guy he was. His dedication to hockey paid off at the age of 16, when he joined the Verdun Junior Canadiens of the Quebec Major Junior Hockey League (QMJHL).

Despite moving from his small Newfoundland home community (population 20,000) to a largely French-speaking suburb on the outskirts of Montreal, Todd immersed himself in the culture and taught himself French. This wasn’t surprising to those who knew him. Todd’s level of intelligence can be best exemplified during his senior year in high school, while still playing hockey in Quebec, when he returned home with six weeks left in the school year. His goal was to write his final exams and graduate with all the kids he grew up with. Mission accomplished.

From the moment Todd first stepped on the ice in the QMJHL, he developed a reputation as a rugged player. His hard-nosed approach to the game meant he was called upon to drop the gloves on a regular basis. By the time he ended his four-year career there, he had amassed 971 penalty minutes in just 265 games. And though he never wanted to be known as a fighter, Todd ultimately would do whatever it took if it meant achieving his goal of playing in the National Hockey League.

Unlike the prototypical hockey enforcer, Todd didn’t just excel with his fists. In his final year, he finished the regular season with 46 goals and a league-leading 102 assists in 66 games. His 148-point total ranked him second in the entire league behind teammate Yanic Perreault.

After his junior career came to an end, Todd spent 10 years in the minor professional ranks playing in Canada, the United States, and Wales. But most teams didn’t see him as a scorer or playmaker — they wanted him solely for his toughness and grit. So, he found himself trading punches for that decade with some of the strongest hockey players in the world.

For a burly guy with a reputation as a fighter on the ice, Todd was a calm, sensitive, and kind individual away from the rink. He would send flowers to his grandmother on special occasions, email his mom electronic greeting cards, and even sold old equipment to help finance his sister’s last year of university.

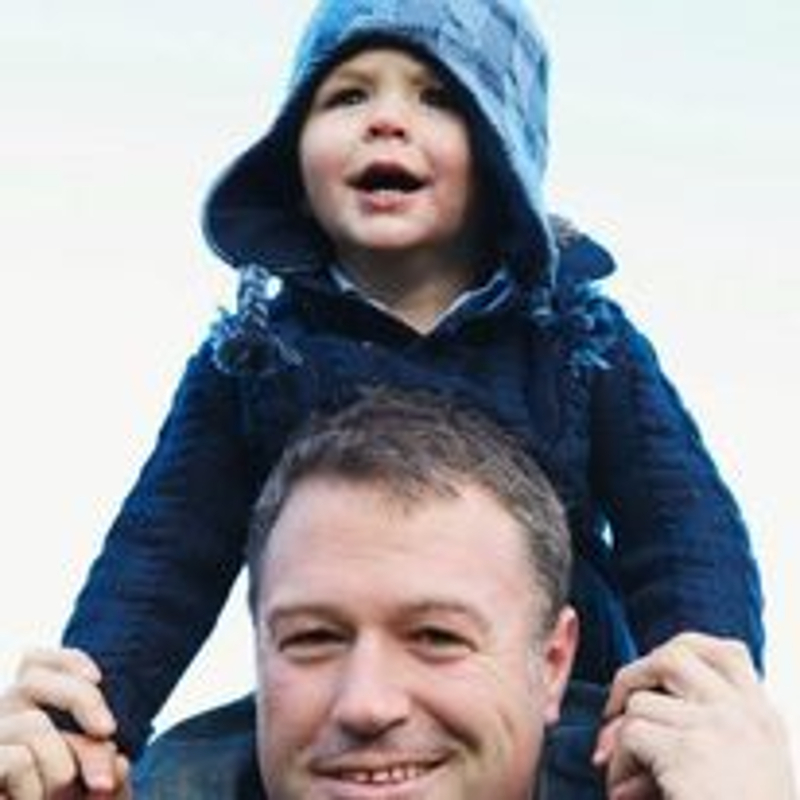

Once Todd finally decided to hang up his skates, he completed his degree and started a family. He put his post-hockey career on hold for a few years to help raise his children, before eventually acquiring a real estate license. He loved his family and was a terrific father, whether putting his daughter’s hair into ponytails and watching her play soccer, wrestling and playing chess with his son, or having the neighborhood kids over for a campfire. He really tried his best to be a good dad.

Todd was diagnosed with more than 30 concussions during his playing career, but it’s suspected the actual number of injuries was much higher. Oftentimes, blows to the head were dismissed, not diagnosed, or left untreated. No one is positive when he first started to show signs of concussion-related issues, but loved ones did notice a distinct change in behavior almost immediately after his playing career ended in 2001. He started partying heavily and living more carefree. And while he remained close to his family, Todd began to bottle his emotions. His family just assumed it was due to difficulty adjusting to life after hockey or struggling with the loss of his father when Todd was 24 years old.

Over the years, as cases of Post-Concussion Syndrome (PCS) among professional athletes became more widely known to the public, Todd began to suspect his mental health issues could be related to the multiple head injuries suffered during his career.

In 2017, Todd’s worries were confirmed.

After traveling to California for medical testing, scans detected several black spots on his brain, an indication that part of Todd’s brain was no longer functioning. Doctors suggested he learn new activities to help encourage brain plasticity and increase neural pathways, not unlike senior citizens who begin experiencing memory loss. Todd began taking piano lessons, doing yoga with his daughter, and even pruning small bonsai trees.

Still, his condition kept worsening.

Soon, Todd noticed seasonal changes directly impacted his emotional condition. He struggled to adjust and experienced increasing head pain. He was at his worst on nights when the moon was full. He tried using a sunlamp during the dark winter months to trick his brain into thinking it was light out and to help with serotonin regulation.

But it became too much for him to handle, and things began to fully unravel.

After being prescribed medication to treat symptoms of depression, Todd began self-medicating. The headaches that had become part of daily life were worse than ever. He battled substance abuse. His marriage failed, his career fell apart, and he ran afoul of the law. He spent countless hours sitting quietly, rubbing his head. His family tried to provide a support system but often felt helpless as they watched someone they loved turn into a completely unrecognizable person.

Todd then developed cataplexy, characterized by transient episodes of voluntary muscle weakness precipitated by intense emotions. He withdrew more from daily activity and cared less and less about living. He would ask if we thought he was a good dad and say how he ruined relationships with special people in his life.

Even during his struggles, Todd was aware of the brain issues that had claimed some of the lives of his hockey peers. In an online blog he wrote on October 18, 2011, titled “Warning Bells Are Ringing,” Todd addressed the recent deaths of former NHL enforcers Wade Belak, Rick Rypien, and Derek Boogaard. Belak and Rypien both took their own lives after battling chronic depression; Boogaard had passed away from an accidental overdose. All three had later been diagnosed with CTE.

Todd wrote: “My problem with all of this is that there is a far greater issue and problem slowly emerging that has not garnered anywhere (near) the amount of attention it deserves, and this problem, unlike the recent onslaught of head injuries and rule changes, has been around the game forever at all levels.

“This past summer three young men… who were playing or just recently retired lost their lives at very young ages, and I find it terribly disturbing how it seems to be all but forgotten. I can guarantee you one thing, that if these tragic deaths would have occurred to some of the game’s higher echelon players, there would have been a full investigation and research carried out by both the NHL and Hockey Canada, as to how and why these types of tragedies can occur to our players, and they would be quick to react and get some damage control done to protect the NHL’s and Hockey Canada’s pristine image.”

“Why do I believe this is the case? Because I have played the game at all levels and have experienced some of these mental health issues that these players have.”

Todd Gillingham died in an alleyway in downtown St. John’s, Newfoundland in the late afternoon hours of Jan. 14, 2023. He was 52 years old. While some speculated his mental health issues may have finally been too much for him to battle, his cause of death was determined to be the same heart condition that resulted in the untimely death of his father Cavin at the age of 46 in 1994.

Well before Todd passed away, he requested his family donate his brain to science in the hopes of finding answers to the question of why he was in so much pain during his final years. As he told them: “If I could go back in time, I would have given it (hockey) all up in exchange for a healthy brain and life.”

Ironically, Todd gave everything to the sport he loved, but the sport did not return the favor.

Richard Howard

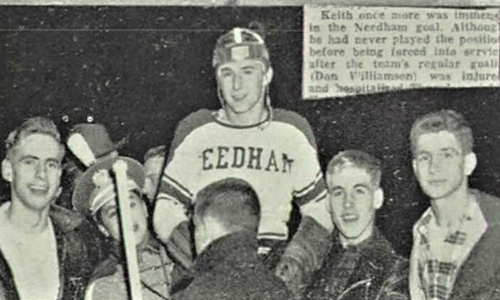

G. Forbes Keith

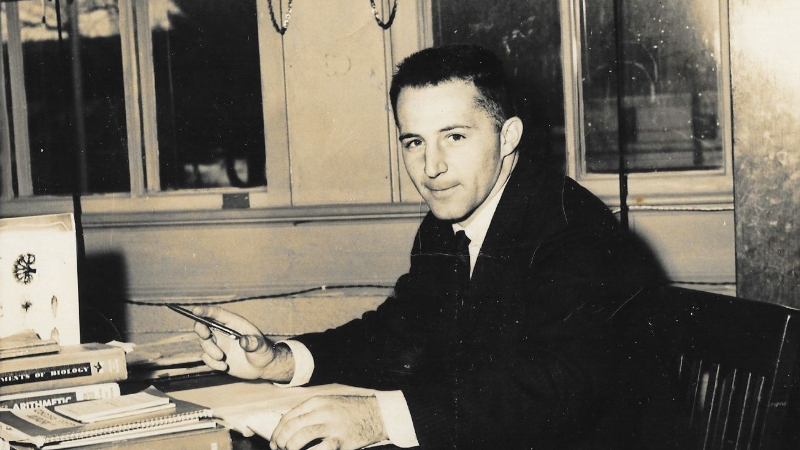

Forbes and I met in September 1955 when I was a senior at Needham High School, and he was a sophomore at Boston University.

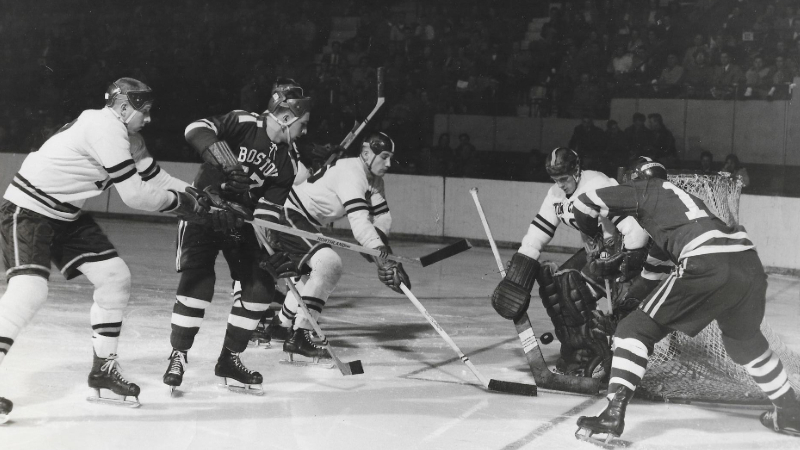

In 1954 Forbes was a member of the Needham High School ice hockey team that won the Massachusetts State Championship. Normally a defenseman or wing, he was called upon to play goalie after the starter had been injured. He was a very good athlete and also played for the BU baseball team as a catcher, first baseman, and pitcher.

He played hockey and baseball at Boston University for four years. He was a member of the first B.U. Beanpot winning hockey team in 1958. He received a B.S. and M. Ed. Degree in Physical Education at Boston University.

We were married at Boston University’s Marsh Chapel in October of 1958 at the beginning of his last college hockey season.

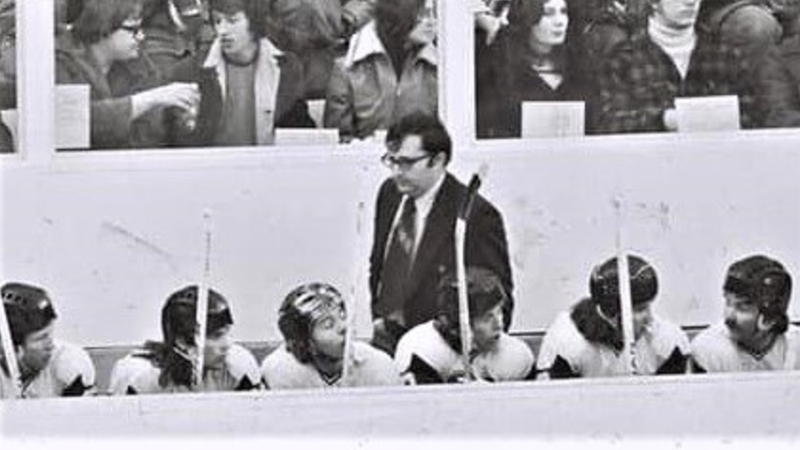

He always wanted to be a coach and teacher from a young age. For 45 years he taught Physical Education and was an Athletic Director and Facilities Director at colleges and high schools all over the country. He also coached hockey, soccer, and baseball at those schools. Additionally, he worked at several hockey camps, soccer camps and other sports camps during the summertime.

He started the Massachusetts Hockey Coaches Association and Massachusetts Soccer Coaches Association along with fellow coaches.

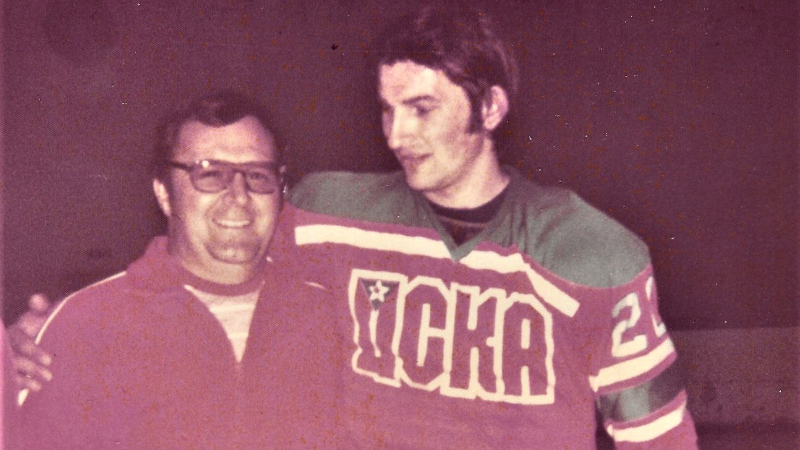

During the late ‘70s Forbes was selected to study in the Soviet Union in recognition of his contributions to the advancement of sports and physical education in North America.

In 1981 we moved back to Needham, Massachusetts to take care of Forbes’ mom. He taught at the high school from which we both graduated. In 1983 we moved out to Southern California where we lived for 22 years and in 2005 after he retired, we moved to Tucson, Arizona.

In his spare time he played tennis and semipro hockey and softball. He enjoyed woodworking and traveling across the country in our RV, visiting 35 states.

We have two children, Scott and Lisa, and three grandchildren, Sam, Ariel, and Aaron.

He suffered from Alzheimers Disease the last five years of his life. We made a donation of Forbes’ brain to the Boston University CTE Center hoping to help find answers for other athletes.

Lyndon Kenny

The following was written by Sheldon Kenny, Lyndon’s brother four months after Lyndon’s death. Sheldon’s story originally appeared in The Sheaf, the University of Saskatechwan’s student newspaper in March 2012.

This past November I lost my brother Lyndon Kenny to suicide.

Lyndon was a very good hockey player. He was drafted by the Brandon Wheat Kings of the Western Hockey League and he was not only a highly-skilled defenceman and strong skater, but also the toughest person I have ever known.

His ability to scare opponents and produce game-changing hits and fights was unparalleled for someone of his age.

Unfortunately, this enforcer style of play made my brother vulnerable to multiple concussions and, therefore, more susceptible to depression.

Enforcers are the designated tough guys on a hockey team. Players in this role often struggle with depression not only because they suffer numerous and severe head injuries, but also because they must deal with the pressure of fighting almost every game in order to keep their spot in the lineup.

Lyndon was no exception.

My brother became addicted to alcohol and drugs at an early age. His addictions carried on through most of his life, even with multiple stints in rehab centres.

He was not a drug addict like those on TV shows, though. He hardly let it show in his personal life. He was the most loving and caring person I knew and was constantly looking out for others.

He struggled to explain his problems to me and our family, however, and for a long time he turned away from those closest to him — as the archetypal tough guy, he tried to cope with his struggles alone.

It was only recently that Lyndon came to understand that he needed help. He began to open up to our family and made an effort to guide me down a better path of life than he had taken.

He had been drug- and alcohol-free for two months before he took his own life on Nov. 1.

The depression and anxiety proved too much for him.

Only a few weeks before his death, Lyndon left a comment on a sports medicine website indicating his struggles.

“I’m 27 and have been on a serious decline since [my] early to mid teens,” my brother wrote.

“I have had hundreds of blows to my head since I was around age five. Most occurred from my reckless style of hockey throughout my teens. Here’s a list of symptoms I have — Lack or loss of knowledge, insight, judgement, self, purpose, personality, intelligence, opinion, reasoning, train of thought, motivation, relationships, thinking, humour, ability to process information and learn, organize, planning, communicating, finding speech, decision making, visualizing, interest, sensitive to sound, ears ring, trouble sleeping, head aches, PCS [Post Concussion Syndrome] etc.”

Lyndon’s comment ended with an appeal: “Protect yourselves and loved ones! What a scary situation. I feel so bad for my family.”

His final wish came in the form of an unsent text message intended for me. Lyndon wanted to have his brain donated to research at the Boston University School of Medicine so we could have the answers he had sought for years.

Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy

Lyndon was adamant that he suffered from Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE).

He knew everything about it and the pursuit of the answers he needed led him to many medical professionals who could have helped him. However, he was extremely frustrated by every doctor’s complete refusal of his claims and he was angry with himself because he felt like he could not explain to them exactly how he was feeling.

It has recently been released that legendary professional hockey players Bob Probert and Derek Boogaard both suffered from extreme cases of CTE, which is no doubt directly related to their roles as enforcers.

When a team needs something to give them a momentum boost, enforcers are counted upon to go out and get a big hit or to get in a fight. This physical playing style leads to more blows to the head, resulting in concussions.

But the evidence does not stop with Probert and Boogaard. Rick Rypien and Wade Belak both died by suicide this past summer after lengthy battles with depression. Both players played a tough game and they no doubt suffered many concussions.

While we have yet to hear the results of the tests performed on Lyndon’s brain at the Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy in Boston (now the UNITE Brain Bank), it is obvious looking back at all the conversations we had and the symptoms he listed that he had battled with CTE for a long time. Update: Lyndon Kenny was diagnosed with stage 1 CTE at the Brain Bank.

Sadly, there is no known way to reverse the effects of concussions. Even sadder is the fact that CTE can only be diagnosed after death.

As of 2009, only 49 cases of CTE have been researched and published by medical journals.

However, the Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy recently began a clinical study of over 150 former NFL athletes aged 40-69 and 50 athletes of non-contact sports of the same age, all of which are still alive and participating in sport. The goal of the study is to develop methods to diagnose CTE before death, which can hopefully lead to a cure in the future.

The future

After witnessing my brother go through all he did, all I want is to see a higher level of understanding for concussions. They can be deadly.

The cultures of all sports, not just hockey, need to change to adjust for this growing problem. Most importantly, the stigma of being the one to leave a game due to a concussion needs to stop because, in hindsight, the ones who take a step back and admit that there is something wrong are the tough ones.

I would be lying if I said I was not scared for myself.

I’ve played a lot of hockey in my life, have suffered a number of hard hits to the head and have been knocked unconscious twice.

In the past few years I have dealt with depression and anxiety and, although it can’t be proven, the fact that they may be a result of my concussions is a very real possibility.

I have also started to notice that I am dealing with some of the same symptoms that my brother felt he was experiencing. I have noticed a loss of personality, intelligence, motivation and humour. My ability to learn and communicate has decreased and I have had trouble sleeping.

I hope for my own and my family’s sake that I am simply reacting to the loss of my brother, but right now I cannot be certain.

Suicide is preventable and help is available. If you are concerned that someone in your life may be suicidal, the five #BeThe1To steps are simple actions anyone can take to help someone in crisis. If you are struggling to cope and would like some emotional support, call the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988 to connect with a trained counselor. It’s free, confidential, and available to everyone in the United States. You do not have to be suicidal to call. If you’re not comfortable talking on the phone, consider using the Lifeline Crisis Chat.

If you or someone you know is struggling with lingering concussion symptoms, ask for help through the CLF HelpLine. We provide personalized help to those struggling with the outcomes of brain injury. Submit your request today and a dedicated member of the Concussion Legacy Foundation team will be happy to assist you.

Eric Lundberg

Warning: This story contains mentions of suicide and may be triggering to some readers.

Eric was a truly caring, sensitive soul, with the very best sense of humor. He was charismatic, handsome, and fit, with a great smile. Most who knew him personally were in awe of his athleticism, which was only rivaled by his determination and competitive spirit. He was a naturally gifted athlete from the time he could walk and picked up any sport with enviable ease. After his professional hockey career, he would often joke about joining the PGA Tour, if he could only spend every day out on the golf course. For so long, sports were his life, and he had a love for them like no other. Playing them, watching them, understanding them. Even the earliest baby pictures show one-year-old Eric with either some sort of ball or a hockey stick.

Looking back at old photos, it’s hard to find many without Eric, an adorable little towhead, in a Whalers or Bruins jersey, or Red Sox hat and coat. Eric’s later success in sports came from more than just natural talent though. He was dedicated and willing to sacrifice more than most could have, or would have been willing to, at such a young age. He truly loved the game of hockey, and it was a huge part of his life from the time he was two years old.

He attended Providence College on a full athletic scholarship, where he met his soon-to-be-wife, Caitlyn. He was drafted in the third-round of the NHL draft at the ripe age of 19. The world was truly his oyster. After graduating PC, he went on to play professionally in the minor leagues for four seasons. By the end of his hockey career, Eric was ready to move onto the next chapter. He and his wife welcomed two of the most beautiful babies into the world. They were Eric’s biggest joy in life and what I think he was most proud of. His love for his children was apparent to all, and Eric couldn’t wait to teach Zoey and Ty how to play the sports which had brought him so much joy. We all thought he would transition from world-class athlete to world-class coach, even if only to his kids.

From the outside, life looked perfect – beautiful wife, two amazing children, a picturesque home, good job, and a rascal of a dog that was Eric’s best bud. However, unbeknownst to most, Eric was secretly struggling. What first manifested as depression and severe anxiety turned to issues with anger, impulsivity, drastic mood swings, drugs, and alcohol. The issues became less of a secret as, what we now know to be the effect of a lifetime of concussions, had more serious consequences. It happened somewhat slowly at first, with some debate as to how serious his issue with alcohol abuse was, or whether the depression could be more appropriately medicated, but seemed to accelerate over the last few years.

Eric tried to cope in whatever ways he could, but what seemed manageable at first spiraled out of control and eventually took over his life, and consequently our family’s lives. Before our own eyes, we witnessed Eric’s kind soul be taken over by demons that seemed determined to destroy everything in his path. We all lived in fear of the next proverbial shoe to drop, leaving us to help clean up the pieces of another mess.

Between the ups and downs of rehab, hospital visits, doctor appointments, accidents, jail stays and ICU admissions, there were glimpses of the man we once knew – the man we were all so desperate to get back. The most heartbreaking moments were when Eric himself seemed to realize something was drastically wrong but was powerless to change it. Those who loved him most were unrelenting in their attempts to help him, but the progressing disease was equally determined to push people away. Watching Eric turn into a person who was unrecognizable left our family shattered and completely helpless, literally on our knees praying for a miracle. Eric didn’t want to be the person he had become, we know that, just as we know he was scared and suffering more deeply than we could have imagined.

After years of struggle, Eric left the world on his own terms by taking his life at just 38 years old. The pain of losing him has been extremely difficult; it has left our family shattered. While Eric physically left this Earth on April 26, 2021, those who really knew and loved him had been grieving him for much longer. In an effort to understand our own experience, and possibly help others, we chose to donate Eric’s brain to the UNITE Brain Bank. The results confirmed what we all suspected: Eric was suffering from stage 1 CTE.

There was nothing anyone could have done to make things better for him, which was the hardest part. Our Eric, who had once filled so many lives with joy and happiness, could no longer face the every day struggle stemming from this irreversible disease. He fought a long battle, every minute of every day. Eric loved his family more than life itself, and while his struggles pulled him away from them, that love will live on eternally. The irony of the fact that the sport which brought him immeasurable joy, also resulted in this level of pain does not escape us. We only hope he has now found the peace he was so desperately seeking, and that his donation will help to find treatment for others suffering from this disease.

Richard Martin

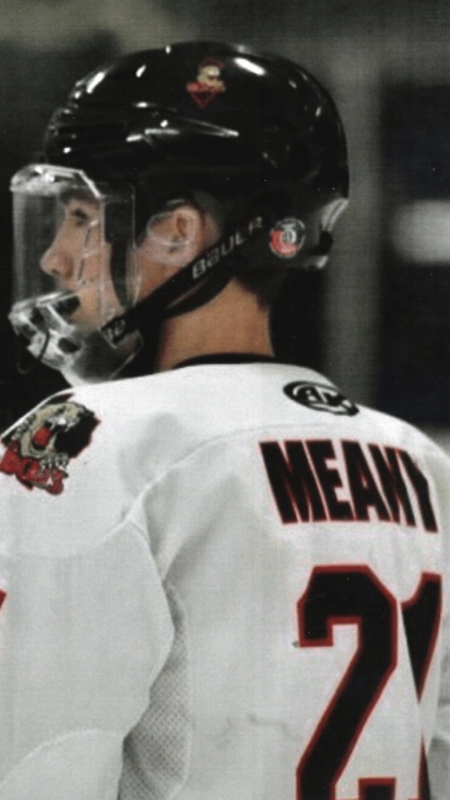

Colin Meany

This article adheres to the Suicide Reporting Recommendations from the American Association of Suicidology.

Sometimes even warriors need to ask for help.

On August 16, 2019, Colin Meany, known as “Patches” to family and close friends, took his own life at the young age of 17 after a two-year battle with significant post-concussion symptoms. It wasn’t until after his tragic death that his family and friends learned the extent of the pain he had been suffering in silence.

Colin was a very popular teenager just a week away from starting his hockey career at the University of Scranton. News of his suicide rocked the Jersey Shore community. Within hours of his death, hundreds of people gathered at a candlelight vigil near his home. Overwhelming emotions of inconsolable grief and shock filled the community. How could Colin Meany, a confident, outgoing student athlete, who always seemed so happy, decide to end a life that seemed so amazing? His own closest friends, who were with him just hours before he died, could not believe what had happened. Later, they began to realize how Colin’s life was deeply impacted by his concussions.

Even the veteran Major Crimes Detectives and other police officers who responded to the Meany home were affected by Colin’s death and discussed how “this one just doesn’t make any sense.”

In a clear and well-thought-out letter to his family and friends, Colin expressed his frustration with his post-concussion symptoms and pain that he fought silently as an athlete. He wrote about his fight with depression and anger for the two years since his concussions. He believed no doctor or medication could help him. He kept those feelings to himself, so others weren’t able to help him find resources for his pain.

Unfortunately, just like so many other athletes, he never fully understood that his painful daily struggles were not uncommon for someone healing from his injuries. Research has shown a link between concussion and suicide risk, with one study finding those who suffer a concussion are twice as likely to take their own lives.

The first concussion

Almost exactly two years earlier, on Labor Day Weekend of 2017, 15-year-old Colin suffered a concussion while playing in a junior hockey game for the Jersey Shore Whalers. Immediately upon speaking with Colin, his father Mike says he knew Colin sustained a significant concussion. During the car ride home Colin told his father it felt like his brain was shaking in his head and he appeared as if he were intoxicated. Without delay, Colin’s parents brought him to a concussion specialist affiliated with a well-known and respected medical center.

During his initial assessment, Colin revealed he sustained what is now believed to be a previous concussion during a game just two weeks before this more severe concussion. When asked by his father why he hadn’t said anything about the prior injury, Colin replied, “I just wanted to keep playing and I knew if I said something I wouldn’t be able to play.”

Approximately three weeks later Colin expressed to his father for the first time in his life thoughts of depression. He texted saying, “This is driving me crazy. I can’t fall asleep, I’m depressed over nothing and it’s just making me mad.”

Colin continued to see the concussion specialist and was medically cleared to return to the ice, which is all he wanted. He once told his older brother Jack he felt his best when he was out on the ice.

Colin returned to play the sport he was so passionate about. He had been playing ice hockey since he was five years old when he started with the Old Bridge Junior Knights. After finally being cleared to play again, he returned to play for the Jersey Shore Whalers and continued to play with his teammates and friends on both the Jersey Shore Wildcats and his high school team at Saint John Vianney High School.

During that time, Colin’s headaches and inability to sleep continued. His parents brought him to a highly respected neurologist who was known for helping patients, including military combat veterans, with post-concussion symptoms. Colin was prescribed medications for the severe headaches.

By all accounts the brief period of depression had been resolved. When repeatedly asked by his parents and during numerous subsequent doctor visits, Colin always denied having any symptoms of depression. None of his family, many friends, teammates, or coaches would have described Colin as depressed or potentially suicidal.

After his death however, Colin’s friends described that after his concussions, Colin would continuously fall asleep in class and would often leave loud parties early (Colin never wanted to miss a party). He would also sometimes want to leave the beach due to the bright sunlight that would cause him to have severe headaches. But he never complained or asked for help.

According to the National Institute of Mental Health, suicide is a complex public health concern, and there is no single cause. Suicide is often preventable and most often occurs when stressors and health issues converge to create an experience of hopelessness and despair.

After Colin’s death, his parents also learned he was texting himself sports-related motivational reminders. It became apparent he knew he needed help but tried to cope on his own.

The hockey community comes together

Suicide impacts communities in profound ways. The outpouring of love and support from the hockey community after Colin’s death was a true testament to his character. More than 1,000 people including so many young men wearing their hockey team jerseys attended the funeral services for their beloved teammate. The young men all described Colin as a tough, gritty, and loyal teammate who always had their back on the ice and made them laugh on bus rides and in the locker room. Even members of rival teams paid their respects and described Colin as a well-respected opponent.

In such a sad and obvious way, the faces of the young people, just like the faces of so many others who attended Colin’s services, were the same. They all showed overwhelming emotions of grief, fear, and confusion. Once again so many people attending the services said, “this just doesn’t make any sense.” Colin kept his struggles to himself.

“Colin was a tremendous teammate and always played with high energy and tenacity,” said Hugh Donoghue, one of Colin’s youth hockey coaches. “Colin was a skilled goal scorer and always found the back of the net when our team needed it the most. I will forever remember his smile and enthusiasm. We were down a goal or two in a game and he said to me don’t worry coach, we got this. True to form he tied the game up and assisted on the winning goal. Colin was beloved and respected by his teammates and coaches.”

Mick Messemer, the current and long-time head ice hockey coach at Saint John Vianney High School who coached Colin for years, described Colin as “one of the best teammates to ever put on a Lancer uniform, regardless of sport.”

“Colin’s love for his school, program, and teammates both on and off the ice will live on forever,” Messemer said.

He also noted that Colin’s work ethic to be the best player he could be was well respected by the locker room and coaching staff.

Even a long-time Jersey Shore hockey referee felt compelled to talk about Colin. Paul Murray described how he spent many hours on the ice with Colin as a referee.

“I enjoyed them all and had so many conversations in between whistles and face offs,” Murray said. “He was genuine, he was funny, he was tough. He was a great kid on the ice, and I enjoyed every interaction with him.”

The Meany family continued to see an outpouring of love and support.

On October 27, 2019, the University of Scranton Ice Hockey Team played the New Jersey Institute of Technology in a Colin Meany Charity game. At the game, Colin’s parents Mike and Karen Meany and his older brother Jack were presented with the #2 Scranton Royals Jersey.

On November 20, 2019, the New Jersey State Policemen’s Benevolent Association Hockey Team played the Saint John Vianney Alumni Hockey Team in the First Annual Colin Meany Memorial Hockey Game. The game was organized by Dan Tacopino, captain of the PBA team who also coached Colin at Saint John Vianney.

There were more than 600 people in attendance to watch the emotional pregame puck drop ceremony when Colin’s father dropped the puck with the PBA Team captain facing off against Jack Meany.

“Colin Meany is one of those kids that you would want on your team,” Coach Tacopino said. “Every sprint he would want to be the fastest, every drill he would want to come out on top, every shift he would want to score or make a big play, and every game he would want to win. Concussion is a serious topic that cannot be overlooked. The fact that Colin put his health aside to assure the team would be successful will show you his dedication and unselfishness he had toward the game he loved. We as coaches, parents, spectators and friends need to assure the health of our athletes. We know a lot of kids who are competitive in their sport and are willing to keep going after an injury. The brain is not a muscle that can recover like a torn tendon or a bruised muscle. You cannot put a cast on your brain or do a certain exercise to rejuvenate it. The brain is a delicate part of the body that needs to be taken more seriously. Colin was a tough athlete and showed no injury. The only time he showed it was when he took his own life. Missing a practice, missing a shift, missing a game can be the difference to a life altering decision. I was Colin’s coach for four years and he always wanted to be the best to ensure his team would be successful. Colin was the true meaning of grit, strength, toughness and heart.”

“Meany was a true warrior,” Jersey Shore sports reporter John Christian Hageny wrote about Colin after the memorial game. “A tough, hard-nosed forward who left it all out on the ice… Injured shoulder in final of the Shore Conference Handchen Cup but kept playing for his SJV team… was a real pleasure covering this young man, rest easy Colin.”

The Meany family wants to thank everyone for their love and support since Colin’s passing. They hope no family has to feel their same unthinkable sorrow. They are pleading to those who are courageously and unselfishly fighting through this battle to speak up about their pain. Mike, Karen, Jack, and Colin’s friends, teammates, and coaches have raised tremendous support for CLF to help prevent future tragedies like Colin’s. We are honored by their generosity after incredible heartbreak and vow to continue to raise awareness, support patients and families, educate the public, and advance research in Colin’s honor. To make a gift to the Concussion Legacy Foundation in Colin’s memory, click here.

Are you or someone you know struggling with lingering concussion symptoms? We support patients and families through the CLF HelpLine, providing personalized help to those struggling with the outcomes of brain injury. Submit your request today and a dedicated member of the Concussion Legacy Foundation team will be happy to assist you.

Suicide is preventable and help is available. If you are concerned that someone in your life may be suicidal, the five #BeThe1To steps are simple actions anyone can take to help someone in crisis. If you are struggling to cope and would like some emotional support, call the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988 to connect with a trained counselor. It’s free, confidential, and available to everyone in the United States. You do not have to be suicidal to call. If you’re not comfortable talking on the phone, consider using the Lifeline Crisis Chat.

In August 2021, Colin’s friends honored him

On Sunday, August 8, 2021, many of Colin’s friends and teammates gathered at a basketball court near Colin’s home for a dedication ceremony for a memorial bench in Colin’s name. The basketball court is a place where Colin would often go to work on his agility skills, always striving to be the best hockey player and teammate that he could be.

On Sunday, August 8, 2021, many of Colin’s friends and teammates gathered at a basketball court near Colin’s home for a dedication ceremony for a memorial bench in Colin’s name. The basketball court is a place where Colin would often go to work on his agility skills, always striving to be the best hockey player and teammate that he could be.

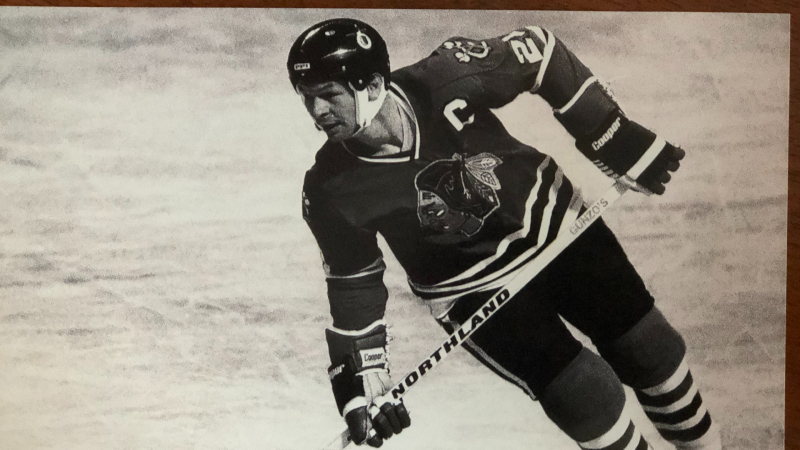

Stan Mikita

It is important to understand the manner in which our father lived his life: his compassion for others, his ability to meet a stranger and make a friend, and his devotion to family and friends defined him. Our father was born in Sokolce in 1940, then a part of communist Czechoslovakia. At the age of 8, his aunt and uncle visited to ask if they could adopt Stan and raise him in Canada. Stan’s mother, Amelia, and father, George, refused. Then came the miscommunication that would change the course of Stan’s life: the hungry 8-year-old came in to ask for a snack. When Stan was sent back to bed without his snack, he cried. His parents thought he was upset because he wanted to live in Canada, so they changed their minds and let him go. That small moment set in motion a series of events that greatly impacted our dad’s life.

When he arrived in Canada, Stan did not speak the language. He looked different than the other kids and he was not with his “real” family. Even though he was 8 years old, he was placed in a Kindergarten classroom due to his lack of English language skills. He was bullied, he was called a DP (displaced person, a great insult), he had no friends, and in his mind, he didn’t have his family.

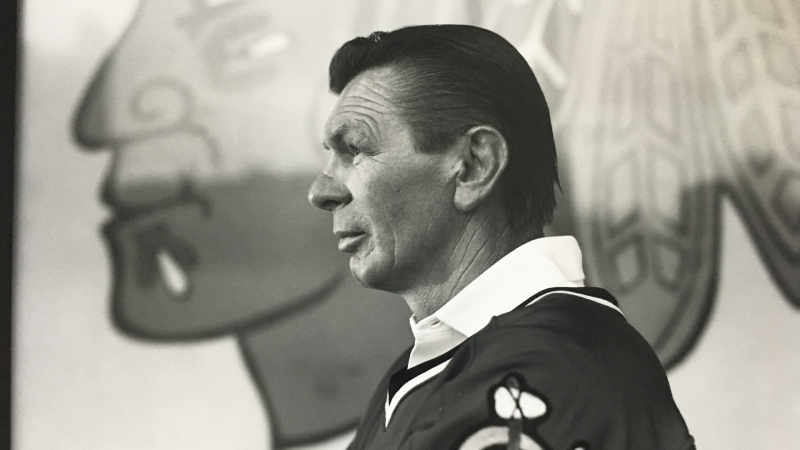

In the midst of that great loneliness, he found the game of hockey, which would go on to become a great joy of his life. While our dad’s professional hockey accomplishments were many, we are most proud of his legacy of giving back and caring for others.

Those early moments upon his arrival in Canada made a lasting and profound mark on our dad. He learned what it was like to be alone in a world full of people, and how to reach out to others who felt that way. Our dad was a husband, father, and grandfather who fiercely loved his family above all else. A friend who would always lend a hand and never missed an opportunity to pull a prank. A kid from Czechoslovakia who never forgot the sacrifices his parents made, his feelings of being different and left out or his humble beginnings. A selfless Chicagoan who felt a duty to give back. A human who saw other people with differences as simply that – people.

As a father, he taught us by example about acceptance, compassion and patience, often reminding us that it doesn’t cost anything to be nice to people. He stressed that everyone is equally worthy of respect and kindness; that people are more alike than they are different. Our dad would ask us if we wanted to go to a track meet or a visit a hospital with him. He never qualified these outings as doing charity work or made note that some of the participants would be mentally, physically or medically challenged. We were just going to cheer some people on. We accompanied him to be “huggers” at the Special Olympics when he helped start the program in Chicago. When our dad and Uncle Irv founded AHIHA (American Hearing Impaired Hockey Association) in 1973, we were all involved from the beginning, helping any way we could. AHIHA is still going strong, fielding the US Deaf Olympic Team. The next generation of Mikitas, the grandchildren, continue to support the program by volunteering on and off the ice. Many of our good friends are AHIHA families. On Thanksgiving we would go to Larabida Children’s Hospital to play and have lunch with the kids and their families.

Several years ago, our father began declining mentally. Almost overnight, our mother’s partner of 52 years was mentally gone but physically still here. Our loving father and doting grandpa was suddenly confused and different from the person we knew.

This new journey was a change for all of us. As a family we decided that it was important to share news of his dementia. Our public statement was met with sorrow, understanding, compassion, love and support for both Stan and our family. We knew we were not alone in this journey, ours was just going to be a little more public than most because of Stan’s name and notoriety.

This is not a path any family foresees for a loved one, but it is, unfortunately, one that unites many of us. One amazing revelation was that once people knew that Stan was suffering with dementia, almost everyone who reached out to us had a family member or loved one fighting the same battle.

Because of the way our dad lived his life, during the end of his life, we were supported and loved by so many of the people he had touched. Friends, former teammates and rivals, kids he visited at schools and hospitals, old neighbors and strangers all reached out to offer comfort and share memories.

In keeping with the way he lived his life as a giver, it was our father’s idea to donate his brain to the UNITE Brain Bank upon his death. He made his wishes abundantly clear, and as he said in his book, “This is a serious issue, and I am willing to be part of a test group. While I’m alive, I will gladly cooperate with the investigation of post-concussion syndrome. It’s the least I can do.” He visited Boston in 2013 to undergo baseline testing with Dr. Stern. He knew this was not diagnostic testing and he would not be receiving any medical treatment to help his memory loss, but that this information would be able to help others in the future. He told our sister Meg after the testing, “I told them they could have my brain, but not yet, I’m still using it.”

Our dad ended his book, Forever a Blackhawk with this quote, “By now, I thought for sure that I would be forgotten. Instead, I am still being remembered. How lucky can a guy be?” We were lucky to have him as a dad and friend, and we are honored to continue Stan’s wish to give back.

-The Mikita Family

Jill Mikita – wife

Meg Mikta

Scott Mikita

Jane Mikita Gneiser

Chris Mikita