Ron Leonard

Ron was born on October 13, 1937, in Roseburg, OR. His parents, Frieda and Eugene Leonard, were farmers from Kansas who moved there during the Great Depression looking for work. He had one older brother, Gordon, who was both his idol and co-conspirator throughout life in terms of mischief.

When Ron was young, his family moved back to a farm in western Kansas, outside of the small town of Quinter. He worked on the farm from a very early age, often rising before dawn to tend to the fields before going to his one-room schoolhouse. He and Gordon would also go hunting for quail and doves in the morning before school, and so he grew comfortable using close-range firearms.

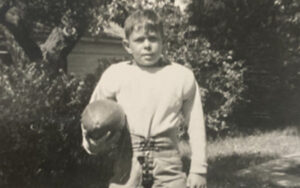

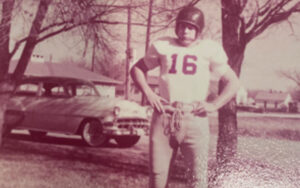

When he was eight years old, “Ronnie” began playing peewee football. At that point in 1945, all the players wore leather helmets and limited pads. Ron was a three-sport athlete through high school: football quarterback and halfback, baseball pitcher, and spring track sprinter. His teammate and good friend Gene Tilton remembers them both having their “bell rung” multiple times, shaking it off, and being put back in the game to continue playing.

After high school, Ron was recruited to play baseball at Kansas State University but pivoted to play football as a quarterback. He spent one year there before taking a sabbatical to “find himself” as a milkman in California. This also could have been a result of having “too much fun as a freshman and not enough time in the classroom,” in his words.

Ron returned to Kansas and transferred to Fort Hays State, starring as a quarterback for his final three years. He recalled multiple instances of suffering concussions, including crashing into an opponent’s bench after an especially fierce tackle in the rain. He recalled that he “came back to, in the huddle,” and barely remembers the rest of the game.

After a successful athletic career at Fort Hays State, Ron graduated with a biology degree and began to teach high school for several years. However, as much as Ron loved teaching and mentoring students, he felt a deep need to serve his country and pursue adventure in the military.

In 1963, Ron was commissioned into the United States Air Force, following his brother Gordon’s path as an enlisted man in the USAF. At the same time, Ron was recruited for the USAF inter-military football team and continued to play there. However, after two years in the Air Force as a communications specialist, he again grew restless in a desk job.

Through a fortuitous contact, Ron managed a one-time transfer into the U.S. Army with no loss of rank. It came with one stipulation – he would have to attend Airborne and Ranger School. His extreme and arduous training prepared him tremendously for extended combat in South Vietnam in 1966. He often remarked that the lessons he learned during those long days and nights saved his and others’ lives in Vietnam.

In November 1967, Ron and his company were at the center of action on Hill 875 at the Battle of Dak To. As Captain and company commander, his involvement and determined heroism are detailed in the book “The Long Gray Line: The American Journey of West Point’s Class of 1966” and “Dak To: The 173rd Airborne Brigade in South Vietnam’s Central Highlands, June-November 1967.”

For his service and bravery, Ron was awarded multiple military medals, including the Distinguished Service Cross (second in recognition only to the Medal of Honor), Silver Star, and several Purple Hearts due to injuries suffered during his career. He was shot in the leg and had a grenade explode in his proximity, leaving shrapnel in his torso which would remain for the rest of his life. At one point, Ron’s compass was shot off his wrist while lying on his back. He was also exposed to blast injuries while calling in air strikes and survived mortar attacks, along with the continuous trauma of being exposed to high caliber firearms at close range.

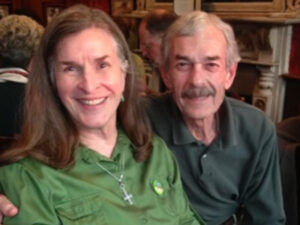

After his first tour in Vietnam, Ron returned to the U.S. and was honored to be selected as an instructor/cadre at the Ranger school in Florida. During the “jungle phase” of the Ranger course at Elgin AFB, he met Dabney Osbun Delaney. Dabney remembers many times where Ron would jump out of airplanes and “bounce” landings, a military term for a parachute failure and a hard landing. He finished his Army career as a Master Jumpmaster, having completed more than 150 airborne operations, i.e., “jumps.”

Approximately 18 months after they met, Dabney and Ron were married. In 1971, he headed back to South Vietnam as a district senior advisor. At one point in time, it was reported that there were no American survivors in his district. Fearing he was MIA or killed, Dabney and their new daughter, Kathryn, waited for information while stationed in Hawaii. A few days later, Dabney received a note from Ron saying he was alive, lying in a ditch, and had been calling in air and artillery fire on enemy positions.

Altogether, Ron ended up spending 28 years in the military with the Air Force and the Army. His service included stations at Fort Bragg, NC; South Korea as the battalion commander of the 2nd Infantry Division in the DMZ, Fort Leavenworth, KS; Carlisle Barracks, PA; Fort Stewart, GA; Fort Monroe, VA; Fort McNair, DC, as an instructor at the National War College, and the Pentagon.

Ron retired from the Army in 1991 and began working as a defense contractor in the Washington, D.C., area. He was stationed at the Pentagon on the morning of September 11, 2001. He and a friend were walking to get coffee when they noticed a female passerby who appeared lost. They reversed course, escorting the young woman in the other direction down the hall. Several moments later, American Airlines Flight 77 struck the Pentagon, crashing into the area where Ron and his colleague had originally been heading. After several hours of no contact, his family learned he had taken it upon himself to hold the door open for thousands of Pentagon personnel fleeing the building.

After many years of combat and defense contracting, Ron officially retired in 2005. He continued to drive thousands of miles to assist with his grandchildren’s care, and to satisfy his love for “packing, moving, and anything orderly.” Ron’s physical health remained excellent, competing annually in his age group at the Pentagon’s Army Ten-Miler.

Slowly, over the next decade, those who knew Ron best began to notice changes. His stories became disorganized, and he confabulated more. He became moody and withdrawn at times and exhibited some uncharacteristic aggressive behavior. At the request of his family, Ron was evaluated by his military health team at Fort Belvoir, VA, between 2016-2017, and was diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment (MCI). As a proud former athlete and military hero, this was a shock to everyone, especially Ron.

In 2018, Ron was inducted into the Army Ranger Hall of Fame at Fort Benning, GA, and spoke to the audience when receiving his award. It was clear at that time he was struggling to communicate his thoughts and was frustrated by his limitations.

As his disease progressed, Ron struggled to function at home. In the spring of 2020, COVID struck and the family was forced into isolation. This period was especially difficult as he also lost his loyal dog, Jack. Going from walking the dog several times a day and exercising, Ron now retreated to sitting in his chair for hours at a time. Dabney noticed a decline in his mood and ability to function on his own.

Ron became dependent on Dabney for most tasks, like what groceries to pick up at the store, how to get home, and grew progressively more confused. In addition, he began to lose significant weight and have sleep disturbances. Ron was often awake multiple times during the night, wandering around and trying to leave the house to go “home.” He would forget the relatives and pets who had passed away and ask where they were.

The family made changes to the home, altering locks to prevent Ron’s wandering and sundowning, removing stove handles, and enlisting a wonderful aide who came and spent time with him during the day. Together, they sang and danced, something he loved to do throughout his life.

In the fall of 2022, after several disturbing episodes where Ron angrily tried to force his way out of the house, it became clear he could not safely be managed at home. Dabney and the family quickly, but reluctantly, decided to move out of their 30-year family home and into a progressive senior retirement community with associated memory care.

On December 1, 2022, Ron moved into his individual room at The Sylvestry Memory Care Center at Vinson Hall, in McLean, VA. The following day, Dabney moved into an independent living apartment across the street. She visited daily and watched as he became quite serene in this new environment. Ron became one of the favorites among the Sylvestry staff. He was known to be a gentleman by all the workers at the facility. As a military retirement memory care center for dementia patients, he was surrounded by other ex-military officers, some of whom he had served with during his career.

On March 19, 2024, Ron passed away peacefully after a brief illness, with family surrounding him. He died with dignity and will be buried at Arlington National Cemetery in late August 2024, with full military honors. In his last hours, the family decided to donate his eyes, brain, and spinal cord to the UNITE Brain Bank.

Ron started contact peewee football at age eight, suffering repeated brain injuries well into high school and college. As a decorated Army Ranger, he also endured multiple blast injuries and stress related trauma. We firmly believe the combination of the two arenas contributed to his rapid decline and ultimate diagnosis of Alzheimer’s dementia and CTE.

Our hope is that Ron’s unique situation of being a high-level athlete and a combat veteran will contribute significantly to the CTE community. If his donation helps identify serum markers which can be used to diagnose and limit further damage during one’s lifetime, his legacy will truly live on indefinitely.

Cameron Adamson

Warning: This story contains mentions of suicide and may be triggering to some readers.

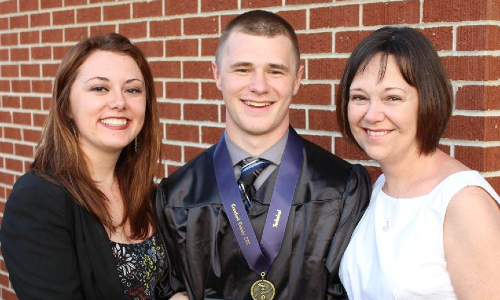

I remember the day Cameron called me at the Pentagon, a week before his high school graduation and proclaimed he was enlisting in the Unites States Marine Corps instead of going to college. Truly not the path I envisioned for Cameron, and a very different path he was about to take. Cameron had a fund already in place to pay for his college, and he was a good student at competitive Conneaut Lake High School in Pennsylvania. Cameron surprised our entire family by telling us he wanted to enlist in the Marine Corps. As I look back, the truth is, his choice in enlisting in the military over college deserved much more than a blank stare.

Since Cameron died by his own hand in January 2021 at the age of 22, over the several months since his passing I have had some says directly to me: “suicide is a selfish act.” I was not angry or insulted, but rather very sad that people still believe this to be true. If anything, in the mind of the one who takes their own life, it’s a selfless act. In Cameron’s case, his writings, and the discussions he had before he died, indicate to me that he felt he was a burden to those who loved him. In his suffering mind, Cameron felt we would all be better off without him.

Based on my experience with Cameron the little I had as his father, I believe his mind was so tortured and he was in so much mental pain, he was not thinking rationally when he took his own life. That is not what I would call selfish. Reading online from most since his death, Cameron was the kindest, most giving and thoughtful man many have ever known, and he would never do anything to intentionally hurt anyone.

Cameron grew up in Saegertown, PA and was an incredibly bright and intelligent kid. Due to the nature of my work in the Navy, I was often far away while he stayed with his mom and older sister in Pennsylvania. Cameron was close with the entire family and despite our physical distance, we still spoke often, and he had a very happy childhood.

Cameron continued to be an outstanding student in high school. He was part of the varsity wrestling team where he excelled but unfortunately experienced a couple of severe concussions.

Communication started to fade during Cameron’s sophomore year. After a few of his head injuries, he felt depressed and pulled away from us a bit. Recovery wasn’t going as expected and he became increasingly frustrated. We were able to reel him back in for a while and it seemed as if he was all set to attend college the following year.

That is, until a recruiter from the Marines reached out and asked if Cameron was interested in joining. The next thing we knew, he was off to boot camp only one week after graduating from high school. He told us he wanted to branch out from what he was accustomed to and have his own purpose in life. After boot camp, he served a four-year enlistment and was deployed for six months to Iraq.

Upon his return, Cameron seemed like a different person. We knew Cameron had suffered from traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) while in the Marines; once in a car wreck and another while on deployment in Djibouti. He was more withdrawn from the family and preferred to be alone. A counselor suggested he was struggling with PTSD, but it was never officially diagnosed. We believe his changes in behavior were linked to the head injuries he suffered both during his time playing contact sports and in the military.

There were so many cracks Cameron fell through. I don’t think he had access to the appropriate resources he was looking for and needed. I was told he was getting help, but no one had any records of his care when I checked. He was passed around from one person to the next until his honorable discharge from the Marines. Though he originally had a job lined up, things didn’t work out as planned. I know Cameron felt left behind, watching his friends from high school going off to college, getting married, and buying a house. Yet here he was with nothing to show for his service.

Cameron was popular, talented, and loved by his many friends and family members. Yet he felt alone in his struggles.

It’s hard to see a possible lesson the moment you get the phone call. It’s difficult to find a meaning when you’re attending the funeral with their anguished mother, sister, and devastated friends. It’s challenging to feel like you’ve somehow been educated in all matters of life and death and the moments in between when you’re struggling to find their last text messages and re-listening to voicemails and holding onto whatever lingering piece of them you have left.

But time as pushed forward and the pain becomes a second skin and the longing becomes commonplace, you realize a death like this, a death that is self-inflicted and self-decided and self-manufactured, is a death with a lot of lessons.

When my son chose to end his own life, I learned that we should not blame ourselves as a family (but it is a difficult task). While there were moments, I believe we could have intervened and things we could have said, the complexity of individual’s decisions and the way in which those choices manifest are too layered and mosaic to possibly understand. We use our own hindsight against us, but even when it is 20/20, it is a filtered view. It is colored in guilt and agony and while it seems clear, it is nothing if not blurry.

I feel situational depression and in the days since Cameron died, believe it is in no way even close to what Cameron must have felt suffering from his depression. The despair and hopelessness I feel as a failed father are so tortuous, I can’t even imagine what Cameron was going through in his final days. A month or so before he died, Cameron told me he was fine and he was working to get his back on track, but also afraid. He could not (or would not) share with me what he was afraid of. Only now do I realize how much he must have been suffering.

I believe there are two possible reasons why some say suicide is a selfish act. The first may be an attempt to comfort the suicide loss survivor(s) in an effort to help shift the guilt burden (blame) to the one who died. The second reason may be that it is easier for them to say “suicide is a selfish act” rather than really try to process why someone would take their own life. Being a suicide loss survivor gives one much more perspective – I hope to use this perspective to educate others.

After Cameron’s passing, his sister Kayleigh suggested donating his brain to the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs VA, Boston University, and the Concussion Legacy Foundation (VA-BU-CLF) Brain Bank. She had done some work and research in Boston for her PhD degree in psychology and recommended we reach out. We immediately agreed since it was a way to honor Cameron’s legacy and allow him to help others even after death. If his donation helps even one fellow veteran, he will have made a huge difference.

While there was no official diagnosis of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE), the researchers found disturbed white matter in Cameron’s brain. There is the possibility he was in the early stages of the disease, but it’s not definitive.

Since my son died by suicide, I learned that we rank death and, in turn, the level of mourning or heartache we should feel about it. While the result is the same, the manner in which a person dies somehow determines the manner in which the people left behind, should mourn. It’s strange, how we quantify death in order to fit our morals or beliefs or feelings of justice and vengeance.

I learned that death, itself, is strange.

I learned that while strangers react differently to the death of another stranger, depending on how they died, loves ones do not. Regardless of who or when or why or how, a loss is a loss to those who loved you most. The pain is the same. The sense of endless longing is the same. The forever wishes to see them one more time are the same.

I learned that if silence wasn’t considered a strength and vulnerability wasn’t considered a weakness, there would be far less funerals attended, and memorials visited.

I learned that there are moments in life, and in death, which do not come with answers. That while we so desperately need to understand the reasons why people do what they do or say what they say or believe what they believe, some things are not meant for understanding. That while it would calm our minds and hearts to know that our questions have conclusions, sometimes, it isn’t about our peace of mind. It is about theirs.

I learned that those left behind are not alone in their pain, nor are they particularly set apart because of it. Others have felt what you’ve felt and have tasted the tears you have tasted and have struggled to adequately describe it all. Just like you.

I learned that there is no single, foolproof path towards healing. While some need to talk, others desperately require the comfort of silence. While some seek solitude, others feel safe in a sea of strangers. While some need to saturate themselves with memories, others need distance and time before thinking about the one they lost. No way is right or wrong.

And I learned that, yes, there is a lesson to be learned at the end of every life, regardless of how that life was lost. That when the pain becomes a second skin and the longing becomes commonplace, you will be changed in a way that is both hurtful and helpful. Despite efforts to get him help, he slipped through our grasp. It is now that I must come to terms with the most brutal outcome for a parent: We could not save him.

And it is that knowledge that, perhaps, can help someone else.

Before it is too late.

I would highly encourage other families of veterans to consider donating their loved one brains as part of Project Enlist. Brain donation helps researchers gain a better understanding of the unique effects of military brain trauma exposure. I myself have also pledged my brain in the hopes of helping advance research for the next generation of veterans and servicemembers.

Suicide is preventable and help is available. If you are concerned that someone in your life may be suicidal, the five #BeThe1To steps are simple actions anyone can take to help someone in crisis. If you are struggling to cope and would like some emotional support, call the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988 to connect with a trained counselor. It’s free, confidential, and available to everyone in the United States. You do not have to be suicidal to call. If you’re not comfortable talking on the phone, consider using the Lifeline Crisis Chat at https://988lifeline.org/chat/

Are you or someone you know struggling with lingering concussion symptoms? We support patients and families through the CLF HelpLine, providing personalized help to those struggling with the outcomes of brain injury. Submit your request today and a dedicated member of the Concussion Legacy Foundation team will be happy to assist you.

Robert “Dice” Allardice

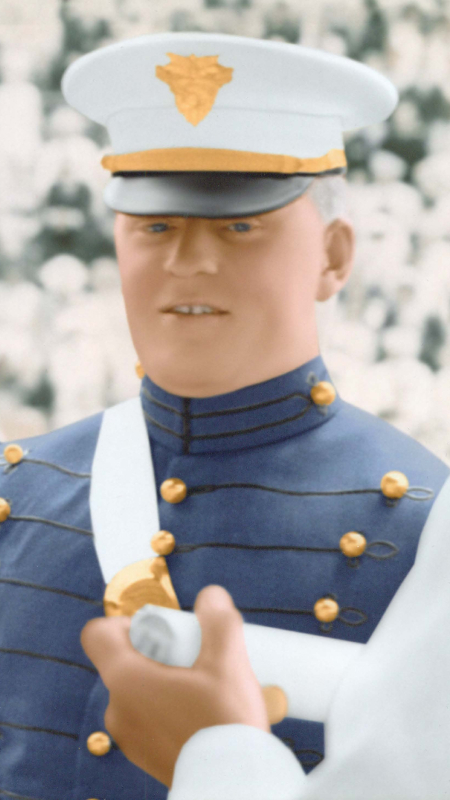

Robert Duncan Allardice was born on July 21, 1947 in Plainfield, New Jersey and moved to Pittsburgh, PA as a child. He was one of six siblings (5th born) four brothers and two sisters. He participated in Boy Scouting and was an Eagle Scout. He earned two varsity letters in football as a DE and HB at North Allegheny High School, one varsity letter in wrestling (180 lb. class) and three varsity letters in track and field for discus where he held a record (which legend has it…still stands). He was captain in track and field and co-captain in football. He went on to play football and wrestle at West Point, graduating with the class of 1969.

In October of 1968 while playing for the West Point football team as a defensive tackle, number 86, Dice sustained three concussions in one week, followed by a broken neck the very next week.

Dice appeared to recover, enough so that he graduated with the class of 1969 and was commissioned in the Quartermaster Corps. He was, however, not medically qualified for the combat arms. While at his first duty station he was rear ended in an auto accident. The resulting injury, along with those sustained at West Point, led to his medical retirement from the Army in September 1970. He joined the work force and had a successful life.

In 1996, the effects of the injuries that had taken away his dreams to serve his country began to manifest themselves more seriously. By his retirement in 2006 he was noticeably struggling, increasingly confused and losing his ability to communicate. His disease progressed quickly, systematically stripping him of his quality of life. During his courageous battle and before he lost his ability to communicate he made the decision to donate his brain to the UNITE Brain Bank for research. Robert passed away at the Durham VA’s Long-Term Community Living Center on November 7, 2014. As the story goes, 10 Games, 4 rushes for 26 yards, and Stage 3 Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE).

Dice became the first known West Point graduate to have died with the disease known as Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE), confirmed by Dr. Ann McKee and the research team at Boston University.

While the effects of his injuries at West Point took away his dreams as an athlete and the ability to serve his country, he never wavered in his love for West Point and his country. I believe, without a doubt that in choosing to be a Legacy Donor, Dice knew he could help to make a difference in the sport he loved. His brain donation places him at the forefront of research being done to develop safeguards to protect against brain injury, diagnose CTE in the living, and eventually find a cure for what is said to be a preventable neurodegenerative disease.

“Dice” was a man who believed that everyone he met held the potential to be his friend. He owned an infectious knee-buckling laugh, and could dance like no other. He was bound by his ties to West Point and the members of the Long Grey Line. He lived Duty, Honor, Country every day. Integrity was how he lived his life. He was fiercely loyal and an honorable man.

Make an online gift in memory of Robert.

Read Robert Allardice’s West Point story here.

Kevin Ash

Brother, Son, American Hero

Kevin Ash loved people. Throughout his life he was a team player, a leader, and a protector of others who understood what it was to struggle and to overcome.

He grew up in the small town of Owatonna, Minnesota with his mother Joy Kieffer and his father Daniel Ash and step-mother Gloria Ash, who lived in Austin, Minnesota. Kevin Ash grew up with his two siblings: older sister Erica and younger brother Conner. As a child, Kevin was quiet, but driven, always striving to overcome learning disabilities. He continually pushed himself to accomplish what was needed to move forward.

Kevin found his place in athletics, where he excelled from a young age. He played tennis, ran track, participated in youth intramural wrestling, and played 4 years of high school football.

He was tenacious. Kevin knew what he wanted and how to make it happen. During his senior year of high school, between football and track season, he signed up for the Owatonna Invite open wrestling tournament, even though he hadn’t wrestled since he was nine years old. To everyone’s surprise, including the bewildered high school wrestling coach, Kevin took third place.

With his physical prowess and big heart, Kevin wanted to serve and protect others. He knew that a career in law enforcement and possibly the military was the path for him. He graduated from high school in 2001, and enrolled in the local community college to begin his work toward a law enforcement degree.

His plans changed after 9/11. Kevin regarded the attack on American soil as an attack on our national identity. It was a personal call to action. Such acts of terrorism had no place in the US, the country he loved. He felt called to protect others and immediately decided to enlist in the Minnesota Army National Guard, where he could be a citizen soldier.

His love for working out, achieving athletic goals, and being part of a team all helped him successfully complete basic training. Kevin never gave anything less than 110% and the Army National Guard gave him the chance to combine his drive and talents with his desire to serve. He was an asset to his unit.

Immediately after completing basic training, Kevin’s unit, the Minnesota Red Bulls, was sent to Kosovo on a police mission. They assisted UN-sanctioned forces in the area. His work included searching houses, confiscating contraband weapons, and locating landmines.

On base, Kevin spent his time laughing, joking, and pulling pranks with his friends. He went to the movies and made frequent contact with his family back in Minnesota, even sharing a picture of a Humvee he somehow got stuck over a gap, balancing on two wheels, 10 feet off the ground. The photo showed he and his comrades standing underneath the truck laughing.

During that first deployment, he was just a 20-year-old guy, out in the world, working hard and enjoying life with his buddies.

When he returned home, he took up martial arts, naturally got his black belt, and started to teach classes.

Things began to change drastically during Kevin’s second deployment to Iraq where he endured the longest deployment allowed for a Minnesota Army National Guard unit: 22 months.

During that time, Kevin was a combat infantryman in Fallujah and was regularly exposed to improvised explosive devices (IEDs). He didn’t share as much about that experience with his family.

But Kevin continued to give 110% to his unit and was recognized for his actions in Iraq, receiving commendations including the Iraq Campaign Medal, the Army Achievement Medal, the Army Good Conduct Medal, National Defense Service Medal, Combat Infantryman Medal, and the Global War on Terrorism Service Medal, adding to his medals from his service in Kosovo.

Kevin truly believed that his service in Operation Iraqi Freedom, Operation Enduring Freedom, and Operation New Dawn was to ensure safety and freedom for everyone, no matter their differences.

When he returned home in 2007, Kevin began fighting a very different battle. He experienced blackouts, dizziness, and symptoms similar to PTSD. He was newly married and his wife had difficulties understanding his mood changes, outbursts, struggles with sleep, night terrors, depression and anxiety. Family members agreed that Kevin had changed after his time in Iraq and encouraged him to seek help through the VA.

While the local VA hospital ascribed his symptoms to PTSD, he fell short of the number required for an official diagnosis. Kevin didn’t want to pursue that line of inquiry anyway because he felt it would have been a black mark on his record and wouldn’t allow him to continue serving in the military or to pursue a career in law enforcement.

Despite difficulties with his memory, Kevin still managed to complete his associate degree in law enforcement in 2009. However, Kevin was unable to secure a position in his desired field. He decided to focus on a military career, earning the rank of Sergeant just prior to his final deployment to Iraq and Kuwait.

Although he was already struggling with symptoms of what we now know was CTE, Kevin volunteered for this deployment because he thought being with his military brothers was the right thing to do.

Several months after reaching Kuwait, Kevin began sending ominous emails saying goodbye to family members, and that he wouldn’t make it back from his deployment. His family worried that he was suicidal and reached out to the military to alert them. Within 24 hours of a phone call by his mother to the Minnesota Chaplin for the Red Bulls, Kevin was evaluated and it was determined that he should be removed from his tour of duty. He was evacuated to Germany, eventually completing his term with the Warrior Transition Unit in El Paso, TX. After receiving psychiatric help for suicidal ideation, anxiety and depression, Kevin was honorably discharged at Fort Bliss in 2012.

Kevin’s struggles continued as he isolated himself from his friends and family. His young wife filed for divorce. He became completely withdrawn, taking a third shift job at a factory that would allow him to work alone.

To help himself cope, Kevin returned to athletics. He began working out, focusing on training to complete in Iron Man event. He started to get into mixed martial arts, and joined a rugby team that seemed to give him a new band of brothers. Slowly, his family thought he was swinging back around to connection, to joy, and to life.

On September 21, 2013, Kevin made an unremarkable tackle in rugby game. The game would mark the beginning of the end of Kevin’s life from CTE. At the time, no one understood how such a routine tackle resulted in such a catastrophic Traumatic Brain Injury. He started breathing erratically, prompting a 911 call, and the first responders called for ambulance transportation. When he arrived at the hospital Kevin’s Glasgow Scale was a 2 (a score of 3 or less indicates the person is totally unresponsive to a set of defined stimuli). The impact on Kevin’s brain was unlike anything the doctors had ever seen, as the neurons throughout Kevin’s entire brain seemed to have sheared away from each other. No one could explain how that hit had caused such a devastating injury.

Kevin was placed in a medically induced coma for two weeks to allow the brain swelling to go down. Kevin experienced continuous seizures as he woke up from the coma.

For two months, he was hospitalized in St. Paul, then moved to the Minneapolis VA hospital for another six months. Kevin was a puzzle to his doctors and therapists who were unable to easily stabilize him and account for such extreme symptoms. He did not respond to treatments in what were typically expected manners. The TBI left Kevin blind, hearing impaired, and with early onset dementia. He was unable to sit or stand on his own, and he struggled to control movements on the right side of his body. The 31-year-old former soldier and athlete was unable to care for himself without assistance and he required constant one-on-one supervision.

Despite his many challenges, Kevin could talk and he often said he felt like he was trapped in a nightmare he couldn’t escape. He said he dreamt in colors and in his dreams he could run, see, and be part of the world again. He could not understand what had happened to him and his life.

Kevin continued to show symptoms that doctors wrote off as anxiety, depression, PTSD, or consequences of the concussion from the rugby tackle. Doctors and therapists never considered that his condition was related to the concussive and nonconcussive IED incidents and combat missions from his deployments. Kevin knew there was something more to his story, but his family struggled to find anyone who would take his whole history into account.

After eight months of hospitalization, Kevin was moved to a group home, where his family insisted that he participate in physical therapy, horse therapy, and contribute by volunteering at a cat rescue. He went to a local fitness center and worked out with a personal trainer secured by his family. His recovery seemed to be going well, but then his rehabilitation progress stopped. His family watched as this young, strong, independent, loving man lost his love of life, his ability to care for himself and he eventually became unable to roll over, sit, walk, or even swallow.

After suffering a fall at his care facility, Kevin’s condition deteriorated rapidly and the medical professionals attributed the decline to “failure to thrive.” He was transferred back to the VA medical hospital in Minneapolis, MN, where he was evaluated, and finally he entered hospice care. Kevin was released from his struggles after just 34 years on this earth when he passed on January 15, 2017.

Since Kevin’s death, his family questioned everything that had happened during Kevin’s deployments, and the final four years of his life. Why had an ordinary rugby tackle resulted in such trauma to his brain? Why had his behavior changed so radically after his second deployment? What was everyone missing?

Their search for answers led them to donate Kevin’s brain to Boston University’s CTE Center where research could provide Kevin with the opportunity to continue to serve and could provide answers for their family.

In July 2017, Dr. Ann McKee called Kevin’s mother and confirmed her suspicions that Kevin’s brain had begun to deteriorate long before the rugby accident. The tackle and subsequent TBI only accelerated his deterioration. Dr. McKee confirmed that Kevin had CTE, likely from the years of concussive impacts to his brain from IED’s and combat. The blow from the rugby tackle was the proverbial final straw.

The last 10 years of Kevin’s life, with all the symptoms that appeared following his first Iraq deployment, started to fall into place. His family is just beginning to understand exactly how much his life and his mind endured. They donated his brain in hopes that through this ultimate sacrifice and service we can start to understand the impact of CTE and diagnose it sooner.

An untitled poem written by Sgt. Kevin Ash

Kevin Ash wrote this poem during one of his tours in Iraq. His mother, Joy, estimates he wrote it around 2006.

Inspired by pain and anger

I continue to force my body to drive on.

This madness inside of me drowns the voices all around me.

Gripped by war, I continue to live on.

Why am I full of this thing inside me?

What is it?

This darkness, this hole that cannot take shape.

I cannot fight its ever-changing shape as it starts to surround me, drinking the light around it.

But even so my feet will not move.

I will not run!

They stay planted in the blood stained ground

Like that of aged oak trees standing against the test time.

Tim Attaway

Daniel Brabham

Daniel Brabham was an Air Force veteran, a teacher, a family man, an accomplished college and professional football player, and a lifelong crusader for change.

A former operator with Shell Chemical, native of Greensburg and resident of Prairieville, he passed away Sunday, January 23, 2011, in Baton Rouge, at the age of 69. He belonged to Carpenters Chapel United Methodist Church in Prairieville. He also formerly taught high school chemistry and math in Tangipahoa Parish. He was a veteran of the U.S. Air Force Reserves. He attended the University of Arkansas and LSU, receiving a bachelor’s degree in vocational agriculture and numerous academic recognitions through honor societies: Omicron Delta Phi, as well as being an Academic All-American.

He played football at college and professional levels, receiving distinction as an All-Southwest Conference recipient (1962) and as the third leading rusher in the SWC during his first year as a fullback. He was the first-round draft pick for the Houston Oilers and later traded to the Cincinnati Bengals, his career spanning from 1963-1968. He was a lifelong crusader for change, having smoking banned in his workplace in the 1980s and founding the Louisiana Fisherman’s Forum. He enjoyed genealogy (tracing his family history to Scotland and organizing reunions), handgrabbing for catfish (featured sportsman in Louisiana Conservationist and in a filmed documentary), aviation (acquired his pilot’s license), writing poetry and music, and spinning yarn surrounded by family and friends. Additionally, he was a steam locomotive and history buff, a self-taught player of the guitar and piano, and an avid reader.

Darrell Burris

On a cool November day in 1934, in a small Oklahoma house with a dirt floor, Darrell Gene Burris began his journey, touching the lives of thousands. What day, exactly, that was, became a point of contention, because the doctor went on vacation and ultimately forgot the exact date he was born.

“I remember,” his mother Ruby would tell him. “I was there.”

From that humble start, Darrell began a life filled with service to others, not only because it was his faith, but also part of his being. He helped his late father Gene Burris paint and wallpaper houses at a very young age. When his sister Paula (Burris) Casey and brother Randy Burris were born, he helped his mother shower them with love.

When he was just 17-years-old, he saw a tall, beautiful girl walking to school and asked if she wanted a ride. Despite being a baseball, basketball, boxing, and football star as well as a handsome high school teen, she told him “no.” Day after day he would drive by her and ask again until finally, she agreed to have a coke with him after school. Less than a year later, when Mary Lou Porter was just 15-years-old she and Darrell snuck off to get married.

For six months they kept their marriage a secret by continuing to live with their families and longing to be together. Her father was furious and threatened to annul the marriage when he discovered it. Darrell fought to keep Mary Lou and they remained married for 35 years until one freezing day in 1987 when she was taken too soon in a tragic car accident on the Overholser Bridge on Route 66 near Bethany, Oklahoma. She was just 50-years-old. He would never remarry.

Besides Darrell’s love for his wife Mary Lou, he loved his family and many friends. He enjoyed the service members he met during his basic training in the U.S. Army at Ft. Sill, Ft. Polk and Ft. Belvoir. He excelled at artillery, but one day he confessed to his commanding officer that he didn’t think he could ever kill another person because he was a Christian. Instead of sending him for further combat training, they sent Darrell to the Ft. Belvoir print shop, where he learned a trade that would carry through the rest of his life.

Civilian life allowed Darrell to use his printing skills by working at several companies including OPUBCO while always dreaming of owning his own shop. In 1979 in Oklahoma City he finally achieved his goal and opened Burris Printing. The company printed material for many clients including Braum’s Ice Cream & Dairy, the National Weather Service Training Center in Norman, Oklahoma, and Stucky’s Diamonds in Houston, Texas, just to mention a few.

When his granddaughter Sarah Katheryn was born, Darrell and Mary Lou’s lives changed forever. After his wife’s death, it was his time with Sarah he said, that saved him. “You’re going to have to learn how to use the dishwasher,” Darrell remembered Sarah telling him. At age 6, Sarah literally saved him when he accidentally caught his kitchen on fire while cooking as he watched a basketball game on TV despite the house filling with smoke. There were also times Sarah tried to force him to eat his vegetables and she would later find them hidden in his napkin. Darrell struggled with diabetes and she would frequently find his freezer full of Nutty-Buddies and chocolate milk.

His Yukon, Oklahoma home frequently became a favorite place for his granddaughter’s giggling teenage friends to hold their slumber parties and New Year’s sleepovers. To this day, a whole generation of Yukon graduates, teachers, and administration staff refers to him as “Papa.”

After retiring from printing, Darrell joined the team at Lowe’s working part-time, always promising his customers 10% discounts. He enjoyed using his time away from Lowe’s at the Yukon Bowling Alley where he volunteered to teach over a hundred children in youth bowling classes. Many of his students even went on to win tournaments. Darrell’s family and friends lost track of the number of perfect score-300 games he bowled but each game would bring a gold ring he kept lined up in his sock drawer.

Darrell joined his wife Mary Lou in Heaven on Wednesday, April 22, 2020. His granddaughter Sarah and his sister Paula lovingly held his hands while playing his favorite Elvis songs.

Those left behind are his sister, Paula (Burris) Casey and husband Mike Casey of Oklahoma City, brother Randy Burris and wife Vicki of Sautee Nacoochee, Georgia, son Michael Burris and wife Susan of Yukon, son Samuel Burris of Los Angeles, California, granddaughter Sarah Burris of Washington, D.C. as well as nephews Michael Siekel and wife Jeri of Oklahoma City, Scott Wallace and wife Jennifer of Southlake, Texas, nieces Jennifer Burris and Andee Allen of Georgia as well as great-nephews and nieces Lucas, Lilyan, Jacob, Brandon Kyle and Dee.

Neurologists were never able to fully diagnose Darrell’s dementia. There were suspicions of Alzheimer’s Disease, questions about CTE and others. So, Darrell donated his brain to the Boston University’s study with the Veterans Administration investigating how concussions can contribute to degenerative brain diseases. The family’s hope is that their struggles to diagnose him and searches for solutions for care can help other families.

Shayne Casteel

Ron Condrey

Ron Condrey was a recently retired veteran of the US Navy from Salisbury, NC, finishing his career as a Master Explosive Ordnance Disposal (EOD) technician and Master Naval Parachutist in 2017. He dedicated himself on countless occasions over 14 deployments, conducting missions around the world in direct support of the Global War on Terrorism. His actions were recognized by numerous meritorious commendations, and for Valor. Throughout his 25 years of military service, Ron sustained a variety of injuries during combat and training, the most harsh of which included a variety of Traumatic Brain Injuries (helicopter crash, Humvee rollover, a fall down a mountain, and repeated blast exposures) and extensive orthopedic injuries, all of which posed significant challenges both during his career and as he made the transition through retirement to find new purpose in the civilian world.

A true warrior whose passion was to serve his country and inspire others, he found purpose outside the military by honoring and supporting our country’s military men, women, and families through his passions of skydiving, athletics, and the outdoors. He captained the Navy’s Warrior Games team and volunteered with Combat Wounded Coalition, Spike’s K9 fund, Navy SEAL Foundation, and Blue Skies for The Good Guys and Gals Warrior Foundation. After retiring from the Navy, Ron and his wife joined Team Fastrax professional skydiving team, traveling the country in support of our veterans and Gold Star families.

Ron ultimately died from the invisible wounds of war, stemming from his Traumatic Brain Injuries (TBIs). He lived in a suicidal state for nearly three years as he transitioned out of the military into civilian life. He felt that he had become a shell of the warrior he once knew: losing executive functioning skills, increased decision-making time, emotional uncontrolled bouts of anger, pushing everyone around him away. For a warrior, these losses meant that his defenses were weak, which resulted in his increased hyper-vigilance and a lack of trust in anyone and anything, to include himself. The TBI symptoms and misdiagnosis of Post-Traumatic Stress (PTS) set him into a downward spiral of depression.

Humans know very little about the brain, and doctors found it easier to diagnose Ron with PTS rather than the unknowns of TBIs. They gave him pills and convinced him that he was haunted by the visions of war, which had not affected Ron to date. Ron went to war expecting to see what he saw and returned a stronger warrior for it. Trusting doctors, Ron went through Prolonged Exposure treatment to “heal his PTS”. Instead of helping, this treatment only emboldened Ron’s feelings of worthlessness. Ron spent years of his life trusting doctors and addressing PTS when he could have been focused on the TBIs. While we have no certain answers about how to heal the brain, and the symptoms of PTS and TBIs overlap, their treatments for the most part do not. For a warrior, a visible wound and scar is a sign of pride. Invisible wounds inevitably result in judgement from bystanders and often loved ones, as they provide no immediate visual story or reminder. Yet they contain pains within the individual for which humans have no pill.

Ron would want his life to inspire you to get out and accomplish something greater than yourself: something you feel is just outside your reach. If something sounds like an extreme challenge, he would tell you not to hesitate and to attack it. He loved the quote, “Life begins at the end of your comfort zone.” Ron has never stopped inspiring, and anyone who met Ron would know that he is grateful his brain and story continue to give back through the Concussion Legacy Foundation.