Robert Fry

Danny Fulton

Drake Garrett

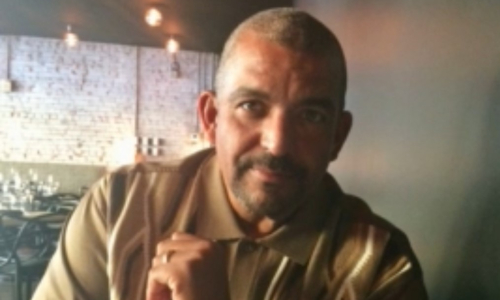

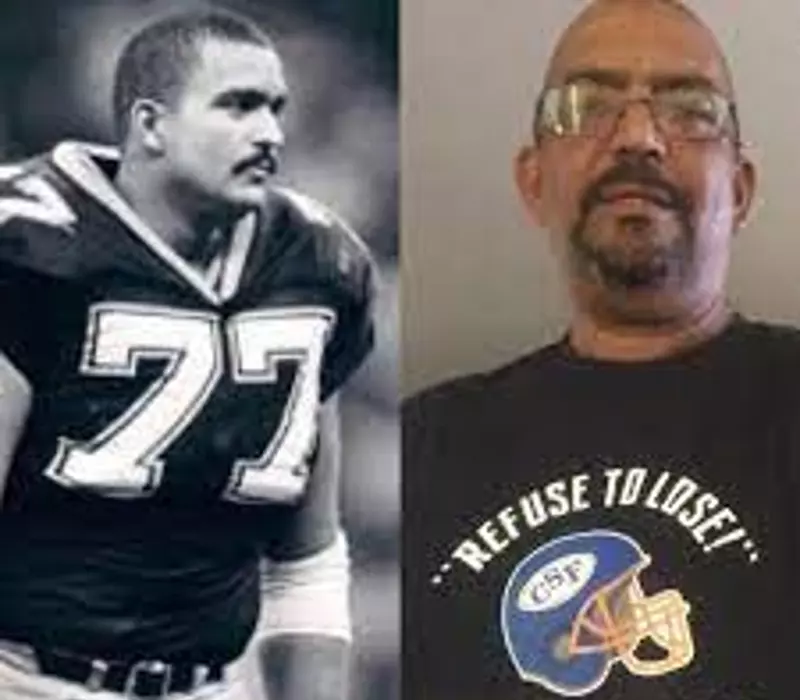

Daren Gilbert

Daren Gilbert was born October 3, 1963 in San Diego, CA. The Gilbert family relocated to Compton, CA, where Daren attended Emerson Elementary School, Ambassador Christian School in Downey, CA, and graduated in 1981 from Dominguez High School in Compton. Daren obtained his Bachelors of Science in criminal justice from California State University Fullerton and later received his Master’s Degree in Education Administration from California State University of San Bernardino.

In high school, Daren played both basketball and football. Football became his passion and he earned a full ride scholarship to Cal State Fullerton. He started in every game for three seasons and was the team’s co-captain. The CSUF Titans won the PCAA Championship in 1983 and 1984, played in the Cal Bowl in 1983 and the undefeated 1984 Titan team was inducted into the CSUF Hall of Fame in 2019. Daren was an all-star selection to play in the East-West Shrine game in 1985. That same year, the New Orleans Saints drafted him 38th overall. Today, he holds the record for the highest NFL draft round pick from Cal State Fullerton. Daren was a member of the first winning team for the Saints. Daren’s older brother, Darren Comeux, also played 10 years in the NFL and in 2009 his son, Jarron Gilbert, was drafted in the 3rd round by the Chicago Bears. All three are proud members of the NFLPA. After the NFL, Daren devoted his life to teaching and coaching. He coached several sports and positively impacted the lives of many youth in Southern California.

What happened to my best friend? A Wife’s Story

Daren had various struggles throughout life after playing in the NFL. Married 36 years, we worked diligently to solve most problems. Daren developed many tools to function in life. We were working with The Cleveland Clinic, Boston University CTE Center, and the NFLPA – The Trust to develop strategies to live a functioning life with CTE. COVID caused new problems. Many of the tools we were using were greatly impacted by COVID and Daren began to change into a different person.

COVID had a drastic impact on our relationship. The restraints of being confined and not following his daily routine made him angry and difficult to live with. I became scared and concerned. Most of his acts of anger were directed towards me and he didn’t remember doing the act after it occurred. My best friend turned into a stranger. Soon the CTE behavior consumed him. This began a downward spiral into a dark world. Daren was a beautiful person murdered by CTE.

On Thursday, August 4, 2022, at home, Daren suddenly and unexpectedly transitioned from this life to eternity. Daren is survived by his wife of 36 years, Alayna McGee Gilbert, his children Jarron Gilbert (Cassandra) and Kourtney Gilbert, and grandchildren Londyn, Jayda and Amari Gilbert, and Laila Criscione. Daren was a great human and will be greatly missed by all.

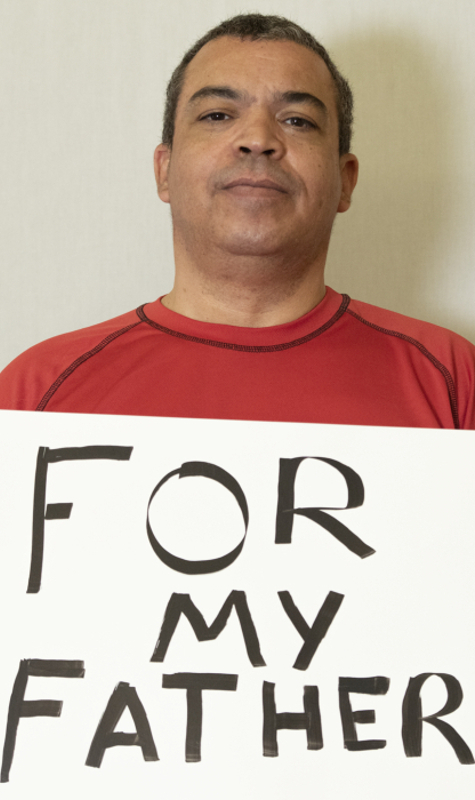

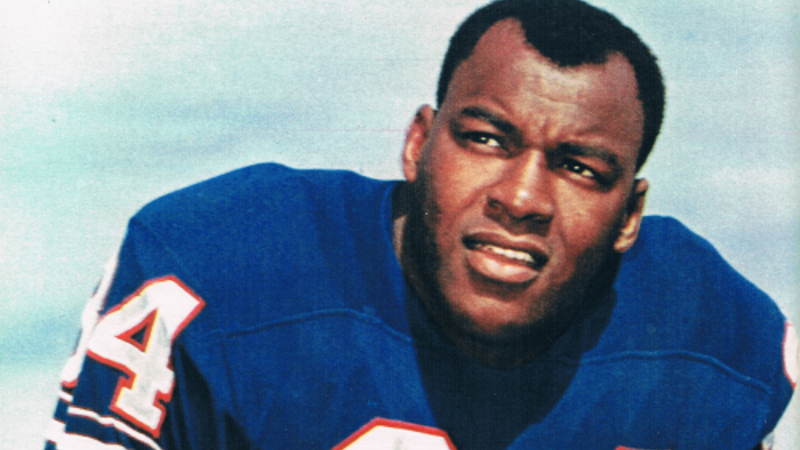

Cookie Gilchrist

“He always took a stand for the rights of others. He often stood alone in his beliefs against all odds. To me, though, he was just my dad.”

A million precious moments and memories

By Jeff Gilchrist

My dad was just my dad to me. Plenty of laughter, tickling, protection and endless affection and love were given to my brother and me.

I am truly humbled as a son, and as a man, to know how many lives he touched with his sincere, undivided attention. He loved to give, share and to live in the moment. This was an important example he embodied in me.

He always took a stand for the rights of others. He often stood alone in his beliefs against all odds. To me, though, he was just my dad. His spirit and essence lives inside of me, and he is not forgotten. His soul lives on with the many stories and tales of this legendary giant among men.

And yet, he was just my dad to me. I am truly grateful for the recent discoveries relating to impact head injuries that now explain the difficult last years of his life. They affected his memories and the moments which he had no control over due to the brain trauma he suffered playing years of pro football.

My precious dad suffered in a horrible way from this trauma. In many ways it stole part of my dad from me. Yet, he is and will always be my dad. My million precious memories will continue to keep him alive for me.

I would like to thank the Concussion Legacy Foundation for their hard work and tireless effort to bring awareness of this issue to all.