Rob Lytle

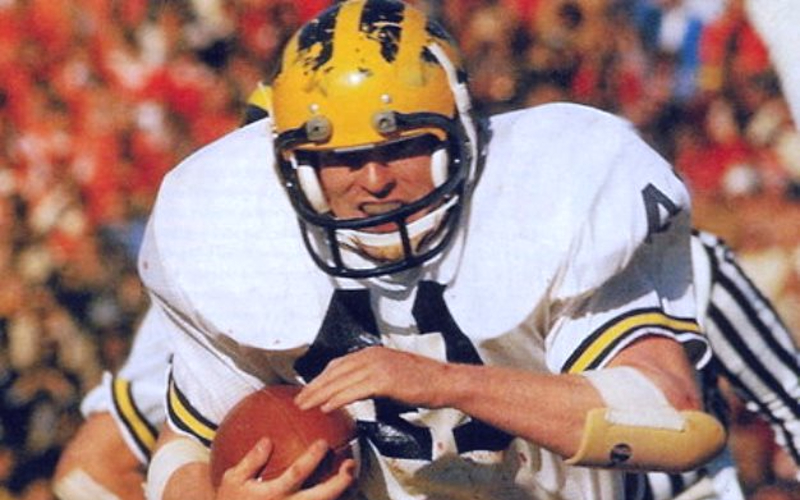

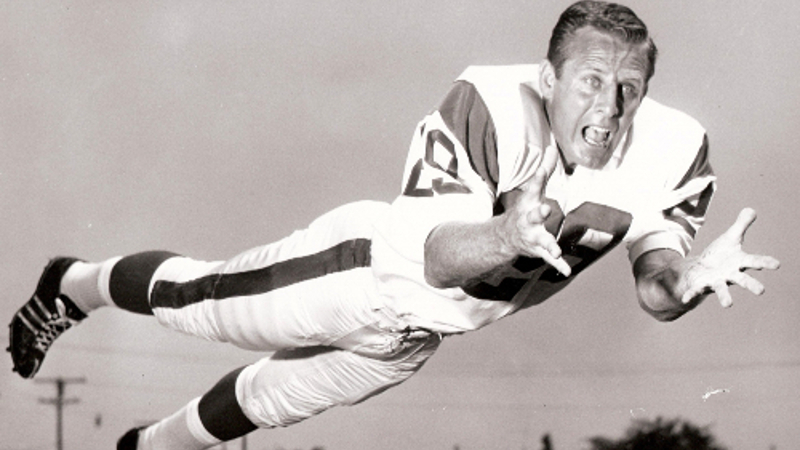

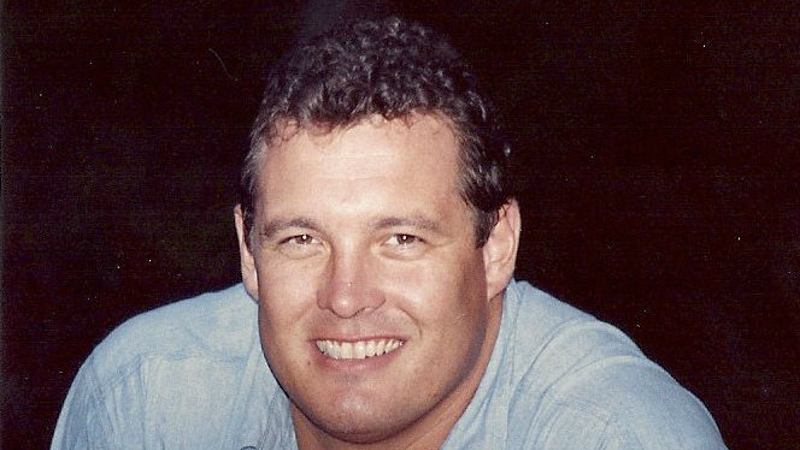

Adding 11 + 20 + 10 gives you 41. My husband, Rob Lytle, wore number 41 on the football field for the Fremont Ross Little Giants, Michigan Wolverines, and Denver Broncos. He wore it in the Rose Bowl and the Super Bowl. Rob died on November 20, 2010. How heartbreaking that he would die on this day.

The events of that day weigh on my heart. Our daughter, Erin, and I were shopping in Columbus. I had left Fremont—the small Ohio town where Rob and I lived—in the morning before Rob was awake. Never a morning person, lately rising from bed and starting a new day had become almost more than he could bear. While leaving town, though, I realized I had forgotten something. At home, I caught Rob freshly awake and struggling to walk down the stairs. As he descended the stairs, I watched his knees refuse to bend. He leaned against the railing, which strained and wobbled loose from the wall, failing against the weight of supporting my suffering husband. Rob grimaced. His many years of football had devastated his body. My heart winced.

Knee operations in the teens had led to an artificial left knee and multiple shoulder surgeries had led to an artificial right shoulder. Rob had mangled fingers that pointed in all different directions. He suffered from vertigo, incessant migraines, and eighteen months earlier had survived a stroke. In recent months, his mood had soured and his spirit seemed beaten. He was distant and depressed—forgetful and lost in our conversations—a cloudy shade of the man I had loved for forty years.

Standing together in the kitchen, Rob prepared to devour a breakfast quiche of eggs, cheese, and sausage. I fussed with a Christmas setting on the table. Just the night before we had carried eight loads of Christmas decorations down three flights of stairs while carols sang on the radio in the background. I kissed Rob goodbye before his first bite, not realizing that this would be my last contact with him.

Every moment in life is precious.

While shopping, Erin and I got the call that Rob had had a heart attack. Life flashed before me. I saw our first kiss and first dance, our last fight and last hug. Was Rob alive? The doctors wouldn’t share anything over the phone. I prayed, wept, and hoped as Erin drove us two hours north from Columbus to Fremont.

Once at the hospital, Erin and I were joined by Kelly (Rob and I’s son). A young doctor ushered us into a conference room. I will never forget the sight of my children falling to the floor in anguish as we heard the news. Our Rob—my Rob—had died. They had just lost their hero, and I had just lost my husband.

The next day, the Concussion Legacy Foundation, then the Sports Legacy Institute, called and asked if we would donate Rob’s brain for their research on head trauma. I had never heard of them or the cause before the call. Rob played in an era when a concussion meant only that you had had your bell rung and where the first fix for an injury was to rub some dirt on it while the second was a series of painkilling injections.

Still, Rob had mentioned many times in conversation that he suffered at least twenty-four concussions that he remembered during his career. One stood out, and I can remember us laughing about it. In 1978, during the AFC Championship game versus the Oakland Raiders, Rob had smashed into Jack Tatum near the end zone and fumbled. Except the referees disagreed and ruled that Rob was down before he lost the ball. Oakland coach John Madden fumed it was a fumble and sprinted along the sidelines screaming at officials. Denver scored a touchdown on the next play, won the AFC title, and played in Super Bowl XII.

In our talks, Rob had told me he didn’t know what happened on the play because he had been “out cold.” He also admitted that he remembered little of the AFC Championship because of the concussion he suffered versus Pittsburgh one week earlier. “I had to play, Tracy,” I can remember Rob saying.

Never did I think that all these concussions could have caused Rob’s changing personality. Rob and I recognized how football had abused him physically and emotionally. What we never realized was the mental destruction the game caused. After the Foundation studied his brain, doctors diagnosed Rob with moderate-to-severe CTE. They told us it was a “miracle” that Rob held a job and functioned in society given the advanced state of his brain’s decay. They were shocked he had been able to mask his suffering. Rob’s somber mood, mental fumbles, issues remembering dates, and recent withdrawn personality came into sharper focus. Before this moment, we had not realized the connection between these problems and football.

Rob’s years of repetitive, violent collisions on the football field had caused CTE. And CTE had caused the change in my best friend of forty years.

Rob was a Fremont Ross Little Giant both on the track and football field where he dreamed as a little boy of becoming a professional football player. We had known each other since 7th grade, but it was while running track our junior year of high school that our lives intertwined. I was captain of the girls’ team, and Rob was the star for the men. During practice one afternoon, the girls were short a starting block and needed to borrow one from Rob. Easy enough. Except everyone was afraid to approach him. He was the star, the fastest on the team, and his sometimes-brash mouth plus the “don’t mess with me” scowl he wore when competing intimidated most.

Not me. When I asked if we could use his starting block, a smile spread on his face and his eyes softened. “Of course,” he replied, and our friendship began.

We dated through high school, spending nearly all our time together. Rob gained over 2,500 rushing yards for Fremont, and in 1972 the Ohio United Press International and Associated Press voted him all state. Coaches from colleges across the country sought Rob’s services. They even knew to call my parents’ house when they needed to find him.

I remember winter nights when the two of us would be outside laughing while digging tunnels or building forts in the snow outside my house. The phone would ring inside as recruiters called to make their pitches, and my mom would holler at us from the window. “Tell them to call back,” Rob would say and laugh. I suppose I could have known then that for him family would always come first.

Rob narrowed his college choice to Ohio State and Michigan—Woody Hayes and Bo Schembechler. Woody would visit Fremont and sit with Rob for hours talking Civil War history and military strategy, favorite subjects for each. He told Rob that he could play as a freshman. Bo said simply: “You’ll never be as great as you are right now. We have six halfbacks already at Michigan. If you come here, you’ll be number seven. Anything that happens after that is up to you.” Instantly, a father-son relationship developed between Rob and Bo.

Rob and I attended Michigan together. When I moved in, several older girls laughed when I told them that my boyfriend played football. “Won’t be your boyfriend for long,” they scoffed. “Good luck,” they mocked. I guess we proved them wrong.

While at Michigan, Rob was a member of three Big Ten championship teams. He ran for 3,317 yards and scored 26 touchdowns. Rob currently ranks 8th in rushing yards in school history and 11th in all-purpose yards with 3,615 on 579 touches. As a senior in 1976, Rob ran for 1,469 yards, was named first team All-American, and the Big Ten’s Most Valuable Player. He finished third in that season’s Heisman Trophy balloting behind Pittsburgh’s Tony Dorsett and Southern California’s Ricky Bell. In 2015, the National Football Foundation inducted Rob into the College Football Hall of Fame.

Before his senior, All-American season, Bo asked Rob if he would play both fullback and tailback—requiring him to sacrifice carries, yards, and a shot at the Heisman Trophy—so they could maximize their talent on the field. Rob made the switch willingly. Michigan led the nation in total offense and won the Big 10 championship that season. Bo always preached, “The team, the team, the team.” Later, Bo would state many times that he felt Rob was the best teammate and toughest player he ever coached—perhaps the greatest praise Rob received for playing football.

Humility, self-sacrifice, and putting teammates above himself mattered to Rob. He loved football and lived to play the game.

We married on June 3, 1977, in Fremont. Since Rob was drafted in the second round by the Denver Broncos, we moved to Denver to begin our lives. Rob was fortunate to spend all 7 years of his professional career with Denver. As a rookie, he scored a touchdown in Super Bowl XII. Even though Denver lost to Dallas, it was an exciting moment in our lives.

While a Bronco, Rob worked at Cotrell’s Clothing Store in the offseason and involved himself in many charities. He served as honorary chairperson for the Listen Foundation, worked with the United Way, and helped with the Special Olympics. He was a fixture at fundraisers during those years.

Injuries filled Rob’s professional career, and it seemed we lived in operating rooms and hospitals. He always worked to overcome them, though, and return to the game he loved. Still, the body—and mind—can only bounce back so many times before it screams no more. In 1984, Rob’s final knee operation was more than his body could conquer. While playing for Denver, Rob scored 14 career touchdowns and ran for 1,451 yards to go along with 562 receiving yards. He reached the pinnacle of his profession, but left regretting that injuries kept him from ever playing to the level that he knew he could reach.

We returned to Fremont in 1984, where Rob worked in his family’s 5th generation men’s clothing store. Retirement was difficult for Rob. Though his heart longed to continue playing, his body could no longer take the physical toll of football. On many nights in the first years after leaving football, we would retreat to the couch after Erin and Kelly had fallen asleep and Rob would sob as I held him. He missed football, but even more he missed the purpose and direction the sport gave him. He believed that he had failed, despite playing seven seasons in the NFL, because he never achieved the impossible goals he had for himself. Over time, we put the pieces together, but Rob’s longing for the game never faded.

Rob closed his family’s store in 1989, and then worked for Bowlus Trucking and Turner Construction. Rob later became involved in the banking business and was vice president and business development officer for a regional bank in Northwest Ohio when he died.

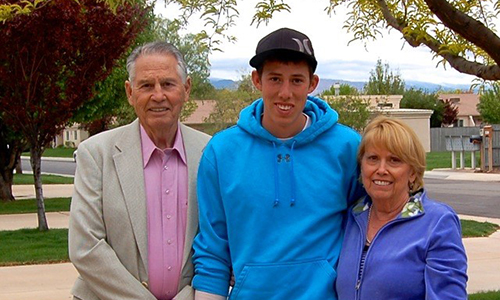

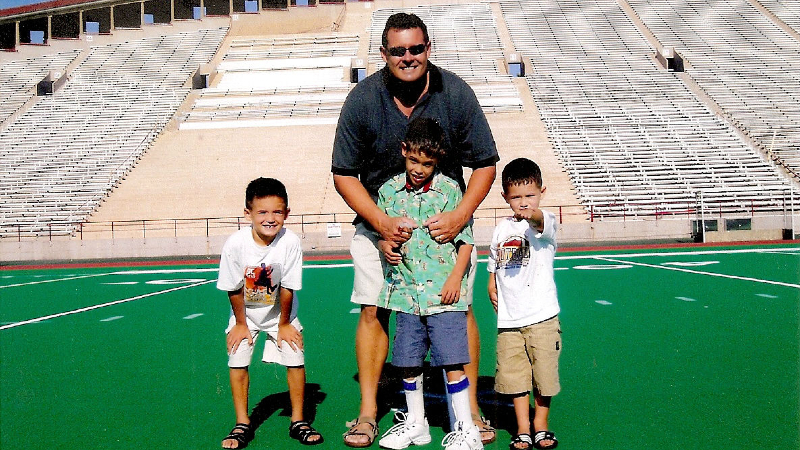

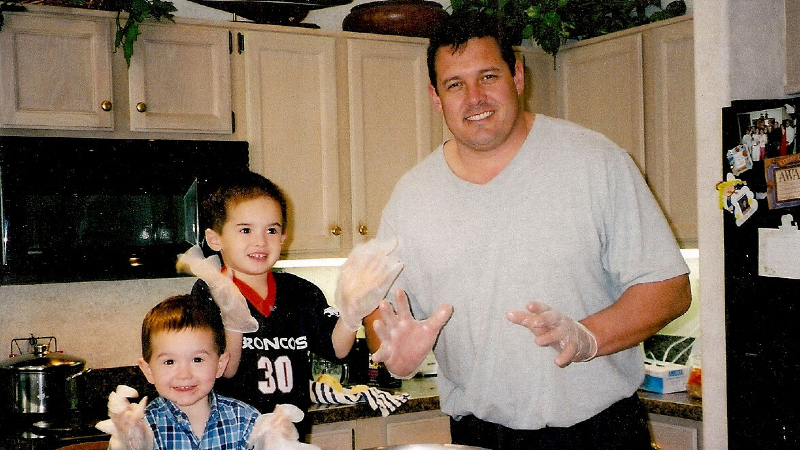

During these years, Rob was a wonderful father and friend. We spent every Sunday with Erin, Kelly, and friends in some pick-up game of softball or football. The lasting memory of Rob for so many people is seeing him with a big smile on his face, surrounded by laughter, and immersed fully in a game or activity with his kids.

Once again, Rob became involved in the community. He was a Rotary president, YMCA board member, and assistant football coach. He served on the board of his favorite organization, the Sandusky County Board of Developmental Disabilities, and they even named their new facility after him because of all the support he gave.

Rob was blessed with a kind and genuine spirit. He invested himself in helping others, and lived his life filled with passion. Rob always wanted to make a difference in people’s lives while striving to include them and put a smile on their faces, which he could almost always do thanks to his sense of humor. Rob believed that every person was important and had a story to tell. He taught our children to be kind, considerate, compassionate, and to care for others. Rob filled our children’s hearts and minds with pleasant memories of meaningful times spent together.

We remember Rob as a loving father who shared the fun and pain of raising a family. Rob always listened, loved, and helped. More than anything else, he loved his family.

Rob wasn’t perfect, but he tried with everything he had.

Charles Mackey

My heart stopped one day in 2006. Charlie did not remember how to get home.

We were on vacation in Mexico where we had rented a condo for several weeks. The condo was situated eight to ten blocks uphill from the little downtown area. To walk to town the route, was one street down and another street up. We had walked it many times.

I felt like I had suddenly taken a punch to the stomach. Then disbelief and denial, until two weeks later it happened again and he was truly lost. A month after we returned home he suffered a small stroke. An MRI confirmed the worst—there were considerable abnormalities in Charlie’s brain. Our doctor in Moab, Utah referred us to Dr. Norman Foster, the Director of the Alzheimer’s Research Center at the University of Utah.

And so began the eight year journey of our “long good-bye.”

In real life, the bulk of Charlie’s career was working in the professional football world as a talent scout, an enviable job he sincerely loved. He traveled constantly from one college campus to another, one practice to another, in and out of rental cars, hotels, and airplanes; seeing “every inch of the USA,” as he used to say. Charlie and I were married in the middle years of his career. It was wonderful to travel with him as he scouted football practices, timed players, while seeing college games all over the country. We watched bowl games and playoff games, and spent one month every April in Chicago for the draft meetings. Twice we were in Hawaii for the Hula Bowl, once traveling with the Chicago Bears to Berlin for an exhibition game between the Bears and the 49ers. Even though his heart and his head were football, he had no trouble switching gears to pursue other interests-reading, poetry and music, just to name a few.

Charlie read constantly. During his early life, he read all the classics, later becoming a serious student of Spanish Colonial history. He read books on everything “New Mexico” (I think we drove on every back road in the state) and often memorized his favorite poems (I did a double take one day when I saw that he was reading the poems of Pablo Neruda, in Spanish). His devotion to his Catholic faith grew as he read book after book on theology, the saints, and the encyclicals of the various popes. He ordered so many books on religion from our local library, the librarian asked him if he was a priest!

He usually listened to classical music, with one exception—Mexican Rancheros—and together we discovered a love for operas. This was Charlie, always surprising me with his myriads of interests. He could do anything with his hands from creating lovely carvings to working with silver jewelry. He even tried painting. He was a meticulous craftsman, a popular handyman, in plumbing, electrical, laying tile, woodworking, or whatever was needed. Our landscaping was cut, mowed, trimmed and then cut, mowed and trimmed again. When the time came that he could no longer read or work with his hands, his interests of course narrowed and he became very happy watching Nova or Nature on television. John Wayne DVDs became his very favorite pastime the last couple of years of his life.

Charlie, was a solid principled man. Once he made a decision he could not be swayed. He was fiercely devoted to his church and was a caring considerate man of the less fortunate. I will always remember his comment that “the poor loved God more because they needed Him more.” It was not uncommon for him go out and help the gardeners or empty our trashcan when the men came by in their truck. Sometimes he went outside with a sandwich or six pack of beer for the workers. Very often he over-tipped the waitress, commenting that “she must be trying to raise three kids” (and then he would give the bus boy another tip).

In contrast, he did not suffer fools gladly, especially the materialistic or boastful. Charlie led a privileged life in the professional football world but never bragged about where he had been and who he knew, you had to drag it out of him. When he wore his Super Bowl ring, it was often turned to the inside unless he was working. I loved that he had real respect for women; a man using bad language around a woman could find himself being promptly escorted outside; the same with the obnoxious cell phone person.

How frustrating it was to deal with my husband as his memory became impaired, along with his very difficult behavior. This six foot three, strong healthy man declined by inches; he who had never broken a bone, suffered a serious injury, been in a hospital, or even taken an aspirin. When he was in social situations, he stopped entering into the conversations, as it was impossible for his brain to process the conversation fast enough to reply. Every day I had to adapt to a new Charlie and figure out a way to cope. This insidious illness robbed him of his ability to take care of finances, think clearly and logically, use good judgment, understand what he had just read, or write letters. He gradually withdrew from his children and grandchildren. My life as his caretaker vanished and his life became my life.

Months and trips to Salt Lake City went by. The doctors watched him and tested him in every way imaginable. Charlie was having more issues with memory and we were both frustrated with each other. I was also having a hard time dealing with his erratic behavior. A second MRI gave the doctors enough information to determine that he had “enormous and confluent” white matter disease, along with other irreversible vascular damage. The doctors told us that medical science had no way to stop the disease from progressing—he had five to ten years.

Close to the time we received Charlie’s diagnosis, Dr. Robert Cantu and Dr. Ann McKee at Boston University Medical School had begun to report their research findings on chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) in deceased football players, linking it to brain trauma from concussions and concluding that CTE continues to progress as it destroys the brain. I was unaware of their work.

Flash forward to 2013. Charlie was in a care center in Salt Lake City. Still unaware of the research being done, I happened to watch the Frontline documentary, “League of Denial” which laid out the published findings of Dr. Cantu and Dr. McKee about CTE along with other medical research on brain trauma. The documentary also included interviews with people associated with the NFL and their reaction. What a shock!

The rest is history. I searched for more information on traumatic brain injuries and ultimately focused on the Concussion Legacy Foundation and Boston University. I contacted Dr. McKee in Boston by email and within a day her team responded. In time, our family made the decision that we would donate Charlie’s brain for their research when he passed away.

Charlie just plain loved his life. I can see him now, throwing out his arms and saying, “What a beautiful day! How much more could a man want but to have a day like this and be with his girl.”

“His girl” was this lucky wife whose husband told her almost every day that he loved her.

Painfully for me, during his last few years he reminded me that we had had a beautiful journey. He needed nothing more and was anxious to meet God. This was his way of indirectly saying to me to be grateful for the beautiful 26 years we had been married. It was the closest he ever came to talking about his illness. This man had no regrets and was perfectly at peace.

After years of caring for my husband with a constant struggle, confusion, sorrow and hopelessness, life suddenly had a purpose. A feeling of great comfort came over me for the first time since that day when my heart stopped in 2006; a realization that maybe the tragedy of his illness could contribute to something meaningful.

Eight months after he passed away, in October 2014, the clinical study and research on Charlie was completed. It was determined Charlie had advanced CTE with a trace of Alzheimer’s and vascular dementia. Although the news was sad, it was a relief to better understand what Charlie had been going through. Dr. McKee told me Charlie must have been very heroic to have suffered with all three diseases without complaint.

Our family is most grateful for the love and sensitivity shown to us by Dr. Ann McKee, Dr. Todd Soloman, Lisa McHale, Patrick Kierman and their team. We spent hours with them on conference calls as they gathered information on Charlie’s life and football career.

We want to express our sincere gratitude to Chris Nowinski and Dr. Robert Cantu who founded the Concussion Legacy Foundation. These two men started asking questions, looking for answers, and found the first donors for Dr. McKee, which we now know lead to the discovery of CTE in professional football players. Without them it may have been years before CTE was linked to contact sports. Chris, Dr. Cantu and Dr. McKee have dedicated their lives to this continuing research, tirelessly working to promote safer sports. Our families’ hope is that the legacy of Charlie and the other athletes who have donated their brains to this valuable cause will be helpful in bringing to light the urgency of understanding brain trauma.

Excerpts From Charlie’s Obituary

Charlie prepared all his life to meet God, and so it was on January 22, 2014 he left this world and completed his journey. He passed away peacefully in his sleep after a long battle with dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Charlie was born in Mescalero, New Mexico, and October 17, 1934 to parents Charles and Katherine Mackey, the youngest of three brothers and one sister. He was of Mexican/American decent; his father being Anglo and his mother Mexican. They moved to Tularosa, NM where Charlie spent most of his young school years. His youth in Tularosa “was glorious”, as he often remarked, always longing to go back to New Mexico. He seemed to identify more with the Spanish side of his world, being fluent in Spanish and loving the people and culture. His Grandfather Miller was a veteran of the Civil War for which he was very proud, and he cherished his Grandfather’s Civil War Reserve Medal.

When Charlie was fifteen his parish priest arranged for him move to Phoenix, AZ and enroll in St. Mary’s Catholic Boys School. He went to school there through high school. At St. Mary’s he was a three star athlete, culminating in a four year football scholarship to Arizona State. At ASU he was homecoming king, a four-year football letterman, and captain his senior year.

After graduation Charlie was drafted by the San Francisco 49’ers, later moving to the Baltimore Colts. He interrupted his professional football phase to fulfill his obligation to the R.O.T.C., serving his country in Korea. While in Korea he played football for the Army, winning the Far East Kimchi Bowl.

Returning to civilian life he spent five years as a football coach at Missouri. The next 22 years he was with the Dallas Cowboys and Tom Laundry as a talent scout. The last eight years of his career he was with the Chicago Bears and Mike Ditka. His career was exciting and successful, but if he were to tell you of what he was most proud it would be his service to his country and his Mexican/American heritage.

Charlie is survived by his wife Diane whom he adored, son Jon, brothers Richard and Howard Mackey; children Melanie and David Watson, Pearson and Sharon Frank, Carter Frank, and five wonderful grandchildren, Laura, Kody, Sam, Savannah, and Cheyenne, who all loved and cared for him during his long illness. Charlie will forever be in our hearts. We miss him.

A memorial mass [was held on March 26, 2014] at St. Vincent de Paul in Salt Lake City, internment [followed] at the Utah Veterans Memorial Park.

In lieu of flowers, love your loved ones and bless every new day.

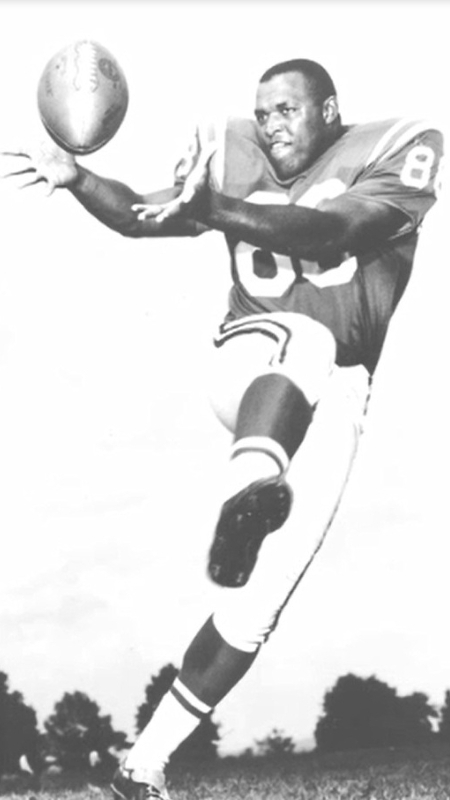

John Mackey

John Mackey made a difference – in football, in business, and in life. A star tight end at Syracuse University, his impact was so significant that the university retired his jersey number – 88 – in his honor in 2007. While at Syracuse, he quietly and peacefully made inroads into the discrimination that permeated society, building lifelong friendships that transcended ethnicity and socioeconomic backgrounds.

Selected by the Baltimore Colts in the second round of the 1963 draft, John played nine seasons with the Colts before finishing his playing career with the San Diego Chargers in 1972. In 10 seasons in the NFL, he earned Pro Bowl honors five times, including his rookie season. In 1992, he was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame, only the second at his “revolutionized” tight end position to be so recognized. To this day, Mike Ditka – the first tight end to be inducted in the Hall of Fame – describes John as the greatest to ever play the game.

In 1970, John became the first president of the National Football League Players Association following the merger of the NFL and AFL. He spent the next three years leading the union through turbulent times, fighting for better pension and disability benefits for players, and gaining free agency that today’s NFL players still enjoy. It was a battle that some contend kept him out of the Pro Football Hall of Fame for 15 years.

Off the field – and for nearly three decades after his football career ended – John was as committed to advocating for those in need as he was to football – and in particular, Syracuse University and the Syracuse Orange, and Baltimore and the Baltimore Colts. Although he and former U.S. Congressman Jack Kemp (an NFL veteran himself) had different political perspectives, they partnered to launch a non-profit to give an educational advantage to disadvantaged children. He actively supported the civil rights movement that changed the course of history. He reached out to others, whether it was to offer guidance on career choices or to advocate for recognition of an under-appreciated teammate. At John’s funeral in 2011, in fact, his Syracuse teammate, former Denver Bronco Floyd Little, told mourners what John wrote to the Pro Football Hall of Fame in support of Floyd’s candidacy: “If there’s no room for Floyd Little in the Hall of Fame, please take me out and put him in.”

That’s the kind of person John Mackey was.

He was also my college sweetheart. We started dating as freshmen at Syracuse, thanks in part to our friend Ernie Davis, a teammate of John’s who loaned him the money to pay for our first date. John and I married in 1964, raised a son and two daughters together, and had just begun to enjoy our grandchildren when John was diagnosed with frontotemporal dementia. He was just 59 years old.

Until then, I thought we would grow old together. I thought we would watch our children’s children grow up. Instead, over the last 11 of our 47-year marriage, I watched the love of my life lose every memory of the family, the friends, and the game he treasured. Over those 11 years between his diagnosis and death, the compassionate person who cared so much for others, the man who stood up for the underdog, the mentor who provided guidance to so many young people, the citizen who gave back to the community – the loving husband, father, and grandfather – slowly regressed to a childlike adult.

Despite the ravages of the disease, there was one constant in John’s mind – he was a Baltimore Colt. When his disease progressed to the point where hygiene became an issue, a fake message from the NFL’s then-commissioner Paul Tagliabue convinced John to brush his teeth. He proudly wore his Super Bowl V and Pro Football Hall of Fame rings, yet it was absolutely heartbreaking to hear him ask friends and fans alike, “Do you want to see my rings?” Even in the fog of dementia, the Baltimore Colts and the National Football League broke through.

Although dementia robbed John of his powerful voice, the disease gave him the ability to influence the discussion about head trauma, to inform active and former players about the dangers, and to impact the future of sports medicine and player safety. His private battle with dementia became the public face of the link between head trauma, chronic traumatic encephalopathy, and related ailments. He was the catalyst for the 88 Plan that provides financial assistance for those affected, for the advocacy and fundraising efforts of his Baltimore Colt teammates that changed the conversation from blaming the player to protecting the future, and for my own involvement in the Concussion Legacy Foundation. When John died on July 6, 2011, a few months shy of his 70th birthday, the widespread media coverage focused as much on these and other post-diagnosis accomplishments as on any of his other achievements in life. Even in illness and in death, he changed the world.

That, I believe, is John Mackey’s greatest legacy. What will your legacy be?

Sylvia Mackey

Mrs. #88

Ollie Matson

Most athletes can only dream of reaching the pinnacle in just one sport, let alone two. Ollie Matson was not like most athletes, however. Not only is he a member of both the College Football Hall of Fame and the Pro Football Hall of Fame, he also won two Olympic medals with the U.S. Olympic track and field team in 1952.

Matson started playing football as a freshman at George Washington High School in San Francisco before joining the University of San Francisco Dons as a star two-way player. He was a 1951 Heisman Trophy finalist following his senior season, when he led the country in both rushing yards and touchdowns. While Matson finished ninth in Heisman voting, his performance led the Chicago Cardinals to select him third overall in the 1952 NFL Draft. Matson went on to play 14 seasons for the Cardinals, Rams, Lions, and Eagles. Throughout his career, Matson was a six-time Pro Bowler, and his 12,799 career all-purpose yards at the time of his retirement ranked second all-time only to Jim Brown. Matson is a member of the NFL 1950s All-Decade Team and was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1972 and the College Football Hall of Fame in 1976.

Upon retiring from football, Matson joined the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum as its director of special events, where he remained until retirement in 1989. Outside of work, Matson dedicated his life to others. He was a passionate volunteer who spent much of his free time mentoring children, especially those in juvenile hall and corrections. Matson also served as a football coach for nearby Los Angeles High School.

But family always came first and foremost.

“My grandfather was a gentle giant, soft-spoken and disciplined,” said Matson’s granddaughter Lara Parker. “He made sure to spend time with all of his children and grandchildren, even though they were scattered throughout the country.”

In addition to being with family, Matson followed a strict daily routine of his favorite activities, including cooking and gardening. He stayed active by walking every day from his home to L.A. High School and back. He also loved watching horse racing but had to stop when his memory began to worsen, as he would forget how to return home from the track.

Once Lara graduated from college, she moved back to Los Angeles to help take care of her grandfather, who had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. As the only person around him full-time, Lara was able to see his changes firsthand. Though Matson never talked about the injuries he sustained while playing football, his wife and twin sister often commented on the amount of hits he took. There were occasions he stayed in bed for days with a headache, only to take the field again as if nothing happened. One particular college game comes to mind: a 1951 matchup against the University of Tulsa. Matson was specifically targeted and hit by the other team for being a Black player.

The always determined Matson slowly started acting in unrecognizable ways, becoming almost childlike at times. Once he reached his 70s, he could no longer drive and did not have the capacity to stay active. There were moments he would forget how to do simple tasks like taking a shower. Matson would get down to play with his grandchildren, but not have the strength to get back up. And though he remained stubborn, he fortunately was never aggressive or physical around people. While Matson’s family originally attributed his decline to Alzheimer’s and old age, they sensed something else more serious might be in play, as news about former football players diagnosed with CTE became widespread.

After Matson’s death in February 2011 at the age of 80, his family made the decision to donate his brain to the UNITE Brain Bank. Researchers diagnosed him with stage 4 (of 4) CTE and noted it was one of the most severe cases they had seen at that time. In fact, they were shocked he was able to survive so long in his condition.

“We discussed the donation before his death, suspecting he was in the end stage of CTE,” said Lara. “The hope was to help future families from suffering like we did.”

Though the Matson family wasn’t surprised by the diagnosis, they were startled by the severity. Because Matson mostly kept everything to himself, they didn’t know how much he was struggling.

“He must have known something was wrong but couldn’t express it,” said Lara. “Was he depressed? Sad? Frustrated? It’s painful to know the strongest person you know was suffering internally and we couldn’t help.”

Lara and the rest of the Matson family want other families who may be in a similar situation to learn from their experience. They are strong supporters of CLF’s Stop Hitting Kids in the Head campaign, which aims to convince sports to eliminate repetitive head impacts under the age of 14 to prevent future cases of CTE. She urges other parents to reevaluate their young children’s involvement in contact sports and the potential risks of pursuing this path.

“Ultimately, we want Ollie’s donation to help further this crucial research so we can truly understand the impact of concussions and related traumatic brain injuries,” said Lara. “We also want others to know no matter how bad something may seem, you’re not alone, and there is a strong network of other families like ours who understand.”

Tommy McDonald

Tommy McDonald told anyone he could to follow their dreams – that anything was possible. He said it because he lived it.

McDonald was born in Roy, New Mexico in 1934. As a kid, McDonald was small but extremely quick. He would give his dad cash he won in footraces. Knowing his son had considerable talent but very little chance of getting noticed by college coaches in Roy, McDonald’s father moved the family to the bigger city of Albuquerque when McDonald late in his sophomore year of high school.

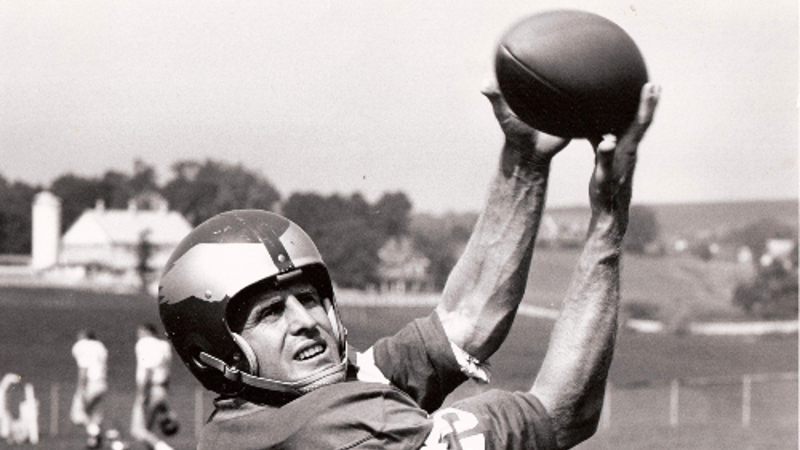

In an era without the assistance of high-tech receiver gloves, many pundits stated McDonald had the best hands in the NFL. McDonald appeared on the cover of Sports Illustrated in October 1962 with the caption “Football’s Best Hands.” But the statement applied to McDonald’s ability to catch footballs, not to the literal shape of his hands. In Albuquerque, McDonald’s father held Tommy back a grade to allow him to grow. In exchange for delaying his schooling, McDonald’s father supped up a motorbike for Tommy to ride around town with. One day, a car cut McDonald off while he was riding, leading his bike’s clutch to snap and completely sever a third of McDonald’s left thumb off.

Despite that, McDonald dominated New Mexico athletics. He won five gold medals in the state track meet, set his city scoring record for basketball, and set the state scoring record for football as a running back. His exploits earned him a scholarship to play running back for Oklahoma University.

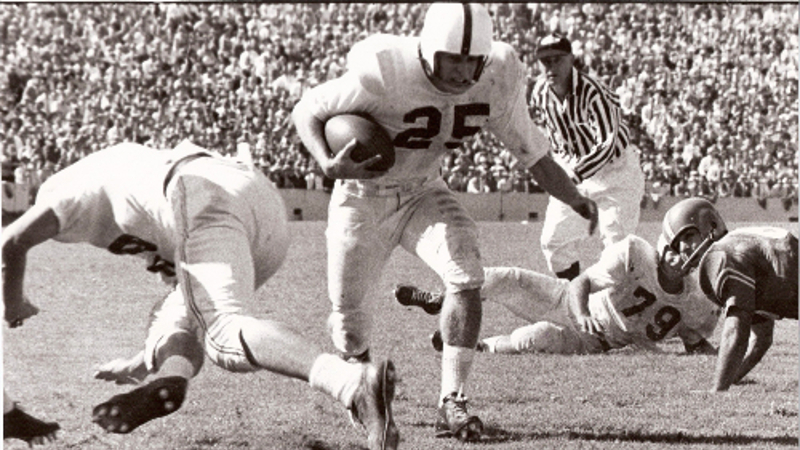

One could argue his career at Oklahoma was one of the best in college football history. In McDonald’s three seasons of varsity play in Norman, the Sooners never lost a game, winning two National Championships over the span. In 1956, McDonald finished third in Heisman voting and won the Maxwell Award, given to the best all-around player in the country.

In 1957, the Philadelphia Eagles drafted McDonald 31st overall in the NFL Draft. McDonald’s exuberance, grit, and production instantly connected him with the city of Philadelphia. When McDonald scored the first touchdown in the 1960 NFL Championship at a snowy Franklin Field, Eagles fans mobbed him in the corner of the endzone.

The Eagles beat the Green Bay Packers 17-13 that day. After the game, legendary Packers coach Vince Lombardi said, “If I had 11 Tommy McDonalds, I’d win a championship every year.”

One of McDonald’s trademarks was springing up quickly from the turf after big hits. Teammate Chuck Bednarik once accused McDonald of getting up too quickly after such hits. But at 5’9,” 175 pounds, McDonald used every tactic he could to convince opponents they could not get the best of him.

McDonald’s son Chris estimates his dad bounced up after a big hit and went back to the huddle following a concussion dozens of times.

There were some hits McDonald could not downplay. He told a story of getting knocked out cold in San Francisco and waking nearly 10 hours later in Philadelphia. Another time, a Dick Butkus hit left McDonald unconscious for more than a minute. He missed only two plays before returning to the game.

“If you looked like you were OK and your cobwebs were clearing, they sent you back in,” said Chris.

McDonald finished a decorated NFL career in 1968 as a member of the Cleveland Browns. He missed only three games in 12 seasons. At the time, a decade in the NFL still meant you would need to find a day job after retiring. His requited love for the people of Philadelphia led him to make the city of brotherly love his permanent home.

He lived outside of Philadelphia and ran an oil painting and plaque business. He and his wife Patricia had four children together. His boundless energy could have powered the stadium’s lights, leading Eagles’ brass to invite McDonald to countless games, team events, golf tournaments, and autograph signings. But after days full of smiling and posing for pictures, he loved nothing more than loading up the family car and going out to Chinese food in Philadelphia’s center city.

“He never bragged about his stats,” said McDonald’s daughter Tish. “He was just dad.”

Just dad became just grandpa. He loved attending his five grandchildren’s games, where he was famous for providing tips to the young players and infamous for pulling pranks on his fellow spectators.

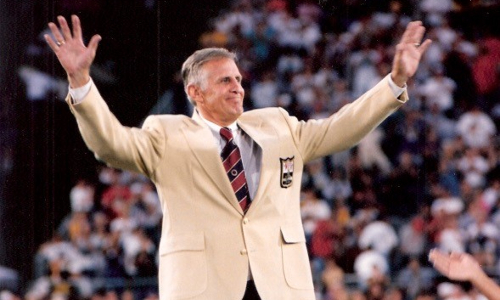

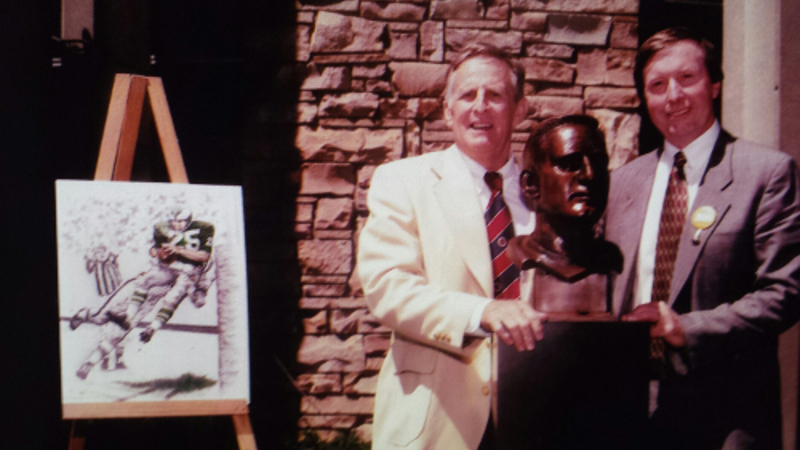

In the 1950s, a young Eagles superfan named Ray Didinger frequented Eagles’ training camp in Hershey, Pennsylvania with his family each summer. He delighted in getting to hold Tommy McDonald’s helmet and interact with his hero as the team walked on to the practice field. 40 years later, Didinger, then a decorated Philadelphia sportswriter, led a campaign to get McDonald inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame. In 1998, McDonald got a call he wondered if he would ever receive. He was to be enshrined in the Hall of Fame that summer.

After Didinger introduced McDonald to the audience in Canton, Chris and many of the family members expected McDonald to share his story of overcoming a small stature and a small town to inspire kids across the country to never give up on their dreams. McDonald went in a different direction. He cracked jokes, tossed his 35-pound Hall of Fame bust up in the air, played the Bee Gees’ “Stayin’ Alive” from a boombox, and chest-bumped all his fellow inductees.

Some members of McDonald’s family were surprised by Tommy’s speech. But for the same reasons he flung himself up from big hits as a player, McDonald explained to his family that his on-stage antics were a way to hide his pain.

By then, McDonald became emotional very easily. His father had passed away four years earlier and his mother was too ill to attend the ceremony. Having been extremely close with both parents, McDonald guessed he would unravel if he started talking about them in a conventional speech. He chose to keep it light instead.

McDonald’s emotionality was one of the first signs of change in his later years. His memory came next.

McDonald had driven the same route from his home in King of Prussia, Pennsylvania to Lincoln Financial Field in Philadelphia dozens of times a year for the past six decades.

But on his way back from a Philadelphia Eagles event in 2008, Tommy McDonald called his wife.

“The car could have been on autopilot, he’s been there for 50 plus years,” said Chris. “But he was totally lost.”

Whenever his memory failed him, McDonald, who never cursed, lamented about “these dang concussions.”

For most of his senior years, McDonald stayed active by playing tennis and racquetball. But McDonald’s cognitive issues escalated when he became more sedentary.

After his induction, McDonald eagerly returned to the Hall of Fame every summer. He loved the honor of being in football’s elite fraternity and enjoyed celebrating each year’s new class of honorees. But McDonald’s memory regressed to the point where returning to Canton provided too many opportunities where he could fail to remember someone’s name. He stopped going entirely.

“He didn’t trust his mind,” said Chris.

Outside of the bursts of emotion, the memory loss and the associated frustration, the McDonald family says Tommy maintained a positive spirit throughout his life. Chris and Tish remember him often saying, “I’m above the grass,” through a giant grin.

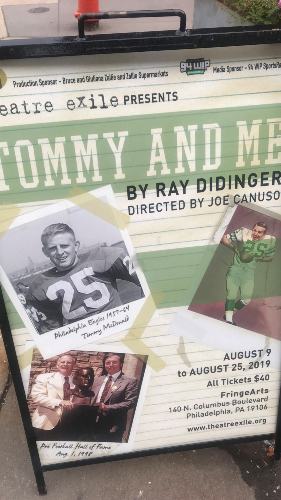

In 2015, Didinger produced a play, titled Tommy and Me. The play celebrated the odds McDonald overcame throughout his life and showed how McDonald made an indelible impact on Didinger’s life. The entire McDonald family attended the first reading of Tommy and Me. McDonald was delighted throughout the reading.

“That was my way of repaying him a little bit,” said Didinger in 2016.

As McDonald aged and his cognitive problems first emerged, Tish, Chris, and their siblings Sherry and Tom assisted with his care. Chris read news of other former NFL players suffering from Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE). The family heard from other football families about former players struggling in similar and different ways as Tommy. It led Chris to decide to donate his father’s brain to research after he died.

“If he could help another player out and make the game better and safer for today’s player,” said Chris. “Then he’s all for it.”

In the mid-2010’s, McDonald’s wife Patricia suddenly contracted Lewy bodies with dementia. She died on January 1, 2018. On the way back from her funeral, Tish remembers her father staring back at him, eyes agape. It was only then that he realized his wife of 55 years was gone.

“That was how bad it got,” said Chris. “He was really out of it.”

Eight months later, on September 24, 2018, Tommy McDonald passed away at age 84.

Chris followed through on brain donation and McDonald’s brain was studied first at the University of Pennsylvania then at the UNITE Brain Bank in Boston.

Tommy McDonald holds several amazing distinctions. He is the shortest player in the Pro Football Hall of Fame. He is one of the last players to play without a facemask. His Oklahoma Sooners’ winning streak of 31 games seems immortal. He holds the Eagles’ record for receiving yards in a game. Now, he is one of the many former NFL players to be diagnosed with CTE.

Dr. McKee, Director of the Brain Bank, diagnosed McDonald with Stage 4 (of 4) of the degenerative brain disease. She said McDonald’s brain pathology explained the massive memory loss he experienced in the last decade of life.

“What I found was classic for long-standing CTE,” Dr. McKee said in a 2021 interview with the Philadelphia Inquirer. “It had all the characteristic lesions around vessels involving a considerable extent of the brain.

For the McDonald family, the diagnosis confirmed what they had already come to realize: more than 20 seasons of football filled with dozens of concussions had done severe damage to Tommy’s brain. Just as proud as McDonald was each year to return to Canton, they are proud to help Tommy give back to the game he loved through CTE research.

Chris and Tish believe their dad’s story of overcoming his size and circumstances, the story he didn’t tell at his Hall of Fame induction, is one anyone can take to heart.

“His number one thing would be to not let anybody tell you, ‘You can’t do it,’” said Chris of his father. “If you have a goal in life, stay determined and persevere.”

For other children of CTE, their message is to relish every moment you get with your parent.

“Enjoy every single day that he’s here, even if it’s a small percentage of him,” said Tish. “Because when they’re gone, they’re gone. You never get to hug them again, give them a simple ‘hello’, or tell them you love them.”

Keli McGregor

Former Rockies president Keli McGregor’s legacy lives on

DENVER (AP) — It’s been a year since Rockies President Keli McGregor, a 6-foot-7 fitness fanatic and former NFL player who was the picture of health, died on a business trip in Utah at age 48, sending shock waves through the club and the Colorado sports and business community.

His legacy lives on in many ways big and small, both in Colorado and in Arizona, where the planning and construction of the Rockies’ new spring training complex in Scottsdale consumed much of his final years.

Wednesday marks the one-year anniversary of McGregor’s death, and reminders of him are everywhere.

The Rockies have painted his initials “KSM” over purple pinstripes inside a giant baseball in right center field. Some players still have his picture on the leaflets handed out at his memorial taped to their lockers.

“I think you see it in the organization that he helped build,” catcher Chris Iannetta (FSY) said. “I think you can see it in the spring training complex that he helped build and I think you can see it off the field in the relationships that he had.”

Manager Jim Tracy said: “I think the first place and the best place to start would be take a walk through our spring training complex. In addition to the Keli S. McGregor fitness area, his fingerprints are all over our spring training complex.”

Iannetta said Colorado’s 12-4 start was directly attributable to the team’s move to spiffy new digs in the Phoenix area. No longer do the Rockies have to make two-hour bus trips between Phoenix and Tucson, where they were often forced to face minor leaguers because other teams were reluctant to bring their front-line players and starting pitchers to Hi Corbett Field.

Iannetta said the players were refreshed when the season started and had already hit stride several weeks earlier instead of having to do so in April, when the Rockies have traditionally gotten off to slow starts.

“I think it’s the continuity of the lineup, the continuity of the guys playing on consecutive days, not having to travel, and facing better pitching,” Iannetta said. “Teams were reluctant to bring their No. 1s down to Tucson, and when we played the Diamondbacks, they never showed us their starting staff anyway. So, I think we’ve benefited from that.”

Regardless of the wins or losses, “he would be proud of us because we go out there every single night and play hard and that’s all he ever asked for,” slugger Troy Tulowitzki (FSY) said.

“And I think not only on the baseball field but I think being good role models off the field is really what he appreciated and standing for the right things,” Tulowitzki said. “And in this clubhouse we have a bunch of really good guys on and off the field and that’s what he’d be most proud of.”

On Wednesday, the Rockies will dedicate a baseball field in his honor in nearby Lakewood, where he grew up.

McGregor, a former NFL tight end, had passed a physical just before spring training last year. He’d later caught a cold, but nothing that would have kept him from accompanying other team officials on a business trip to Salt Lake City.

When he didn’t meet them in the lobby one morning for their flight home, police were called and found his body in his hotel room. It was later determined the father of four died from a viral heart infection.

McGregor’s loss shook the sports communities across Colorado, where he was a multi-sport athlete at Lakewood High School, starred as a tight end at Colorado State and was drafted by the Denver Broncos. He also played for the Colts and Seahawks before going into coaching and then embarking on a career in sports administration, joining the Rockies in 1993.

Commissioner Bud Selig called McGregor “one of our game’s rising young stars.”

His widow, Lori McGregor, told the Denver Post during spring training that tests after her husband’s death revealed he had a degenerative brain disease called chronic traumatic encephalopathy, which causes memory impairment, emotional instability, erratic behavior and depression and eventually develops into full-blown dementia.

She said her husband suffered a couple of concussions in college and was transfixed one day when he saw an ESPN report on former NFL players suffering from debilitating depression. Although he displayed no symptoms, he wanted his brain and spinal cord donated to the Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy based out of Boston University, she said.

CTE can develop when an athlete is exposed to hits that result in concussions or even as a result of repetitive nonconcussive contact, according to the center.

A cross-section of his brain was tested and came back positive for CTE, Lori McGregor said, telling the Post: “That has truly been the answer to my prayers about this, because I understand now that’s why Keli went, that’s why God took him. Because CTE is ugly and there’s no way to treat it. I really, honestly know that’s why (the heart virus) happened.

“He let a great man die a great man.”

Tom McHale

Beloved husband, father, son, and brother

When he died in May, 2008, at the age of 45, Tom McHale became the second former NFL player diagnosed with CTE by the research team at the CSTE at Boston University School of Medicine. Tom was my husband, the father of my children, brother to four siblings, and my very best friend. I hope that sharing Tom’s story will bring attention to the very misunderstood and unappreciated danger of concussions. I hope to help others understand just how devastating the long-term impact of repetitive sports-related head trauma can potentially be. I would hope that the awareness of these consequences will lead to a profound cultural change in how we perceive and respond to sports-related, and other, head trauma.

Tom and I met in August, 1986, as I was entering my sophomore year at Cornell University. I was just 19 years old; he was 23. I was a manager in charge of the defensive line for the Cornell Big Red and Tom was a defensive lineman.

Tom was kind of “larger than life” on the Cornell team. He had given up a full scholarship and a starting position on the defensive line at the University of Maryland to transfer to the Ivy League university to attend Cornell’s top-rated School of Hotel Administration. He’s been described by many to have been in a class all his own, breaking school records and earning All-American honors. When his years of eligibility were up at Cornell, Tom went on to play nine years in the NFL with the Tampa Bay Buccaneers, the Philadelphia Eagles, and the Miami Dolphins.

Tom loved football; but it, by no means, defined him. It was his character that made Tom stand out. I never saw in him even the hint of a suggestion that he thought himself better than another. He filled a room with his presence and always drew a crowd around him. Yet he left so many who met him with the feeling that they had been the most important person in the room and that Tom had been riveted by whatever they had to say.

It always seemed that Tom had goals for his life, and he expected to succeed. He had a great deal of confidence in his abilities and he was proud of his accomplishments; but he never allowed success to go to his head. He always maintained that the ability to play football at its highest level is a God-given gift and he was grateful for the opportunity.

He was passionate about life. He had a beautiful smile and he smiled often. He loved music. He was fascinated by world history. He was enamored by, and gifted in the art, of cooking. But most of all, he was passionate about his faith, unswerving in his desire to do what is right, extremely devoted to his family, and incredibly loyal to his friends.

Tom and I were married on February 3, 1990. We were married for eighteen years and I truly believe that Tom brought me more happiness during those eighteen years than most people will experience in a lifetime.

We had three sons over the years. TJ was born in 1994, Michael in 1998; and Matthew followed in 1999. Tom was devoted to his boys and they adored their father, their coach, their hero.

The fairy tale ended on May 25, 2008 when Tom died from an accidental overdose. It’s still hard to believe it could have ended so tragically. And I still cannot revisit the memory of that day without experiencing physical pain. But truly, looking back, I realize that Tom had been slipping away from us for some time. It just became official and final on May 25th.

There is no way to adequately describe the change in Tom over the years except to say that it was so gradual that I’m not sure when I actually became aware of it. I just know that there came a day several years before he died that I could no longer deny that there was something terribly wrong with my husband. The man that I so admired had become like a shell of his former self, almost as if the spark was slowly being extinguished. And the man that remained made me feel at times that I was living with a stranger.

It wasn’t as though this stranger was a bad guy. He wasn’t. He just wasn’t my Tom. The man who once loved to get up and watch the sun rise had trouble getting out of bed at all. The eternal optimist who approached goals with great confidence had difficulty following through on his intentions.

The man who relished his friends and his family picked up the phone less and less frequently. The man who used to plan lunch while eating breakfast and plan dinner while eating lunch even began, more often than not, leaving the cooking to me.

What appeared to be symptoms of depression may have first come to my attention when Tom complained one night that the pain that he lived with as a result of so many years of pro ball had become too great to be on his feet all day.

He said that owning and operating restaurants, that which he had dreamed of since he had been a boy, was no longer enjoyable. He got out of the business. But that didn’t help. Eventually, he got help for his depression and we hoped that that would be the answer. It wasn’t.

Then one day, Tom confided that he was physically dependent on doctor prescribed pain meds. And so began a terrifying and difficult battle against opiate addiction. And as crazy as it may sound, I was relieved because I now had an explanation for what had happened to my husband and that brought me hope that I would one day have him back.

I believe that Tom fought with everything he had left in him to win that battle. But even in the absence of the drugs, I didn’t see my old Tom return. Though there were glimpses, they didn’t last. And I became increasingly concerned that there was something else going on and more and more afraid that I would never have back the incredible man I married.

When Tom died, I had never heard of CTE, nor did I have the slightest suspicion that the changes I had been seeing in my husband had anything to do with his lifetime of participating in contact sports. And yet when I learned of his diagnosis and saw images of his brain, when I heard Dr. McKee’s explanation of the pathological findings…that Tom’s brain exhibited significant pathology in areas that control inhibitions, impulsivity, insight, judgment, memory, and emotional lability,…my heart ached. But, for the first time in a long time, I felt I was beginning to understand.

I often wonder what Tom would have thought if he had heard of CTE. I wonder whether it would have made a difference for him to know that his inability to live up to the expectations he set for himself might actually have had a neurological cause.

I know that for me, for our boys, and for the many loved ones he left behind, knowing had made a tremendous difference. I have no doubt that I would have agonized over the years, wondering whether it was possible that CTE had been a factor in my husband’s struggles and ultimately in his death.

I’m extremely grateful for the insight that his diagnosis provides. I’m even more grateful to the researchers at the CSTE for their dedication and determination to discover how to diagnose, treat, and prevent this devastating disease so that future athletes need not experience the kind of turmoil that Tom experienced and that their families need not endure the agony of watching helplessly from the sideline.

I know that everyone who had the pleasure of knowing Tom during his lifetime would agree what a tremendous loss was brought about by his death. It is my fervent hope and prayer that all who knew and loved Tom will help me keep the memory of him alive for our boys so that they will remember him as he had been and will grow up to proudly be just like their dad.

Click here to read the New York Times article.

Click here to watch a video about Tom McHale.