Robert Sowell

Leonard Sparks

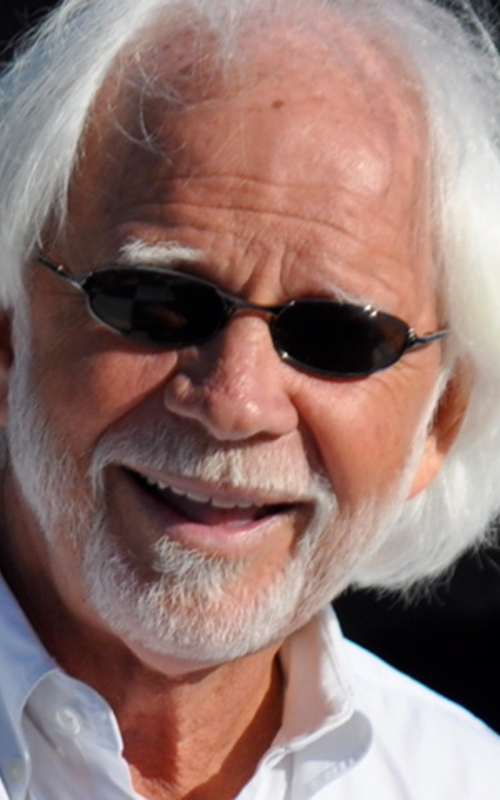

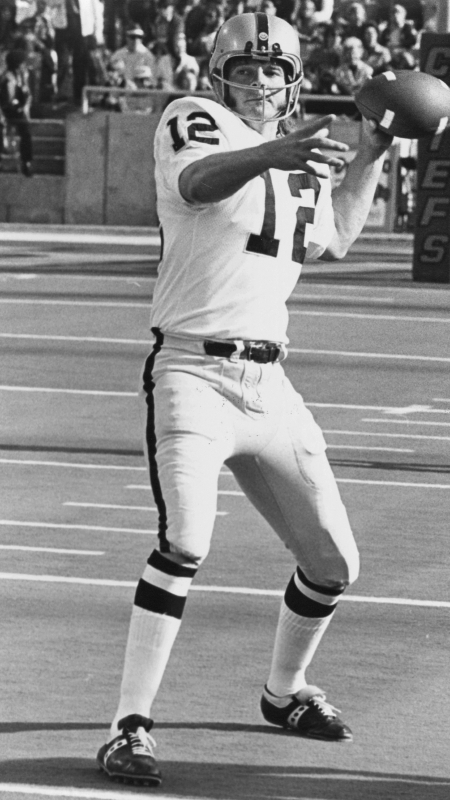

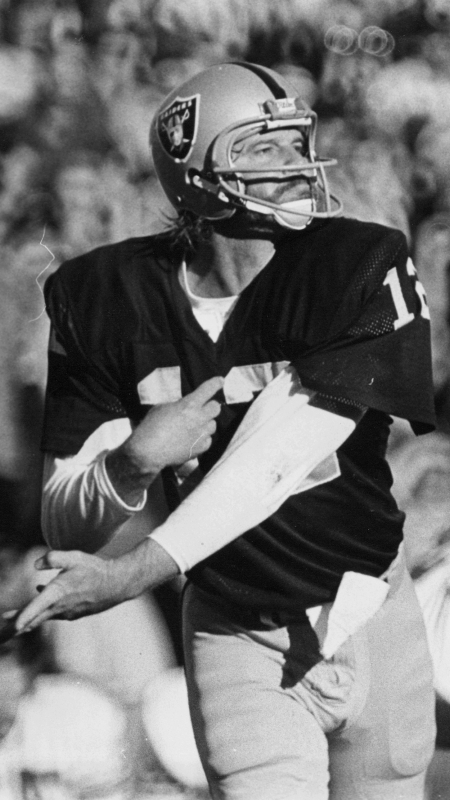

Ken Stabler

The full NFL story cannot be told without Ken ‘Snake’ Stabler. Some of the greatest moments of the 1970s included this football legend. After his death in July 2015, Ken Stabler was posthumously inducted in the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 2016.

Stabler was a stand out when he played college football for the University of Alabama under the tutelage of legendary Coach Paul “Bear” Bryant. He earned a National Championship ring with the Tide and in his senior year lead his team to a stunning 11-0 record, winning the Sugar Bowl where Stabler was selected as MVP.

Stabler was drafted in the second round of the 1968 NFL Draft by the Oakland Raiders. Stabler first attracted attention in the NFL in a 1972 playoff game against the Pittsburgh Steelers. After entering the game in relief of Daryle Lamonica, he scored the go-ahead touchdown late in the fourth quarter on a 30-yard scramble. The Steelers, however, came back to win on a controversial, deflected pass from Terry Bradshaw to Franco Harris, known in football lore as the Immaculate Reception. He also orchestrated other iconic plays; “Ghost to the Post”, “Sea of Hands” and the “Holy Roller.” Stabler had a remarkable 15-year career in the NFL and spent a decade with Hall of Fame owner Al Davis’ Silver & Black.

During his 10-year career with the Oakland Raiders, Stabler was the 1974 NFL MVP, made the Pro Bowl four times, was the NFL’s leader in touchdown passes twice, and earned a Super Bowl ring with a win over the Minnesota Vikings in Super Bowl XI. He also spent time with the Houston Oilers and New Orleans Saints during his playing days.

A remarkable career on the field and a remarkable man off the field, Stabler lived life to the fullest. He went on to entertain his legions of fans as a sports analyst for CBS, Turner Sports Network and for the University of Alabama’s Crimson Tide Sports Network. He also was a highly sought after public speaker and spokesman for various national and regional brands and corporations.

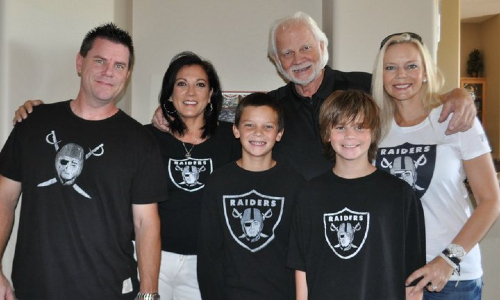

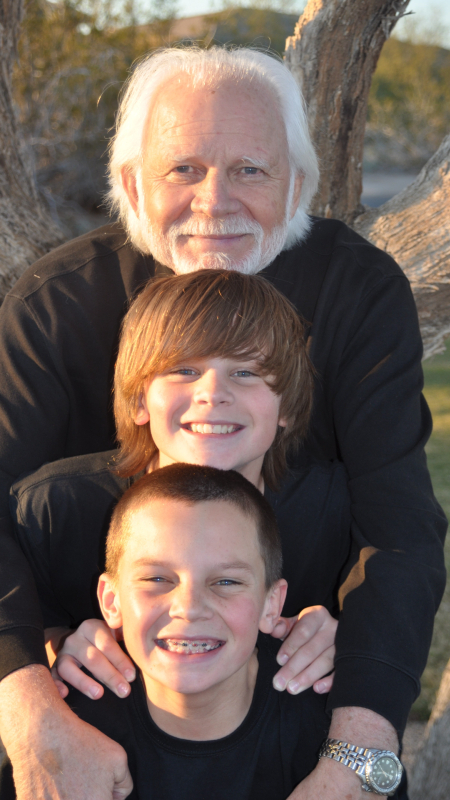

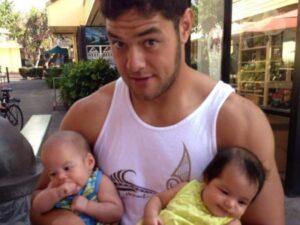

But the job Stabler coveted most was definitely that of being a Father. His greatest joy in life came in the gift of three beautiful daughters whom he adored; Kendra, Alexa and Marissa. And in 1998 when Kendra gave birth to twin sons, Jack and Justin, Stabler became Papa Snake and found glory in the best position ever, that of Grandfather.

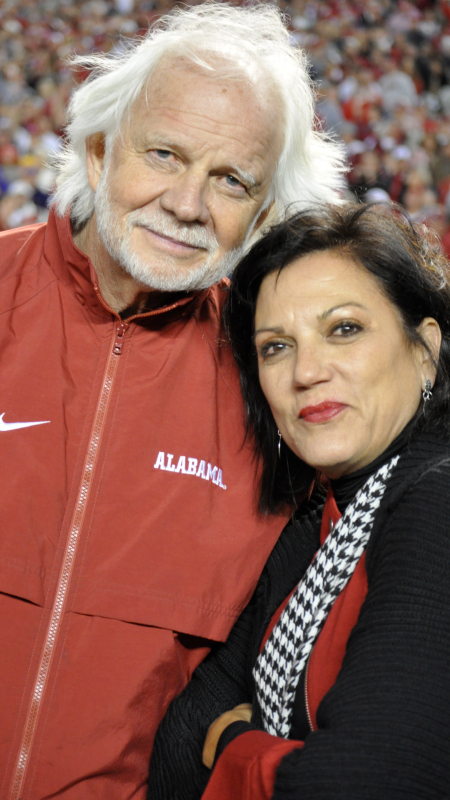

I was Ken Stabler’s partner the last sixteen and a half years of his life, or as I like to say, I played the fourth quarter with him and we won. Even though my life with Ken had nothing to do with the game of football there were parallels you could not deny; he was a fierce competitor, a leader and a victor in his campaigns to help those in need. Whether it be the $600,000 he raised through his celebrity golf tournaments to build the Ronald McDonald House in Mobile, Alabama or his contributions to Cystic Fibrosis of Alabama, the American Heart Association, the American Cancer Society and many other non-profits, he was there to lead the way and battle the cause presented. Stabler founded the XOXO Stabler Foundation, a 501(c)3, in 2003 to raise funds for various causes. Upon his death we have decided that the battle we must continue to wage a war against is that of traumatic brain injury caused by contact sports.

In my opinion, Ken may have eluded the worst of CTE. The beast of colon cancer trumped the impending perils of CTE. After interviewing his daughters and me, Dr. Ann McKee concluded that Ken must have done a “great job compensating for the level of brain damage” he sustained and what is now clearly documented.

His story may be different than most. Ken was of clear and present mind the day he walked into the hospital only to die of complications from the cancer that took his life five months after being discovered. We did see signs of what was to come and undoubtedly the CTE would have progressed to the point of robbing him of his mind.

His daughters, grandsons and I witnessed changes in Ken that were increasingly becoming more obvious. Kendra and I noticed him often repeating himself and he was sometimes confused at stop lights and four way stop signs. He had chronic headaches that went on for days, he described them to be like constant thunderous collisions in his head. The never-ending high pitched sound of tinnitus that simmered all day and night, making it difficult to sleep. He often would look at me and say, “bang, bang, bang” nodding his head all the while trying to explain the noise that just would not go away. He grinded his teeth to the point that he destroyed a bridge in his mouth. When sound and light continued to cause discomfort, he slowly surrendered some of the things he enjoyed the most; his love of music, the volume of sports and CNN. Even the simple day-to-day rituals of me cooking a meal would force him to leave the room and seek shelter in some place of quiet that never quite existed.

As deeply as we miss him in our lives, I think we would all agree that he had lived a great life, and when the clock finally stopped, maybe he had been as elusive with CTE as he had been on the field where he achieved such greatness. He will forever be missed in the lives of all who loved him and the millions of fans who cheered for him on Sundays. His light shines bright and it always will.

Jeff Staggs

Justin Strzelczyk

Lineman, Dead at 36, Exposes Brain Injuries

WEST SENECA, N.Y., June 13 — Mary Strzelczyk spoke to the computer screen as clearly as it was speaking to her. “Oh, Justin,” she said through sobs, “I’m so sorry.”

The images on the screen were of magnified brain tissue from her son, the former Pittsburgh Steelers offensive lineman Justin Strzelczyk, who was killed in a fiery automobile crash three years ago at age 36. Four red splotches specked an otherwise tranquil sea — early signs of brain damage that experts said was most likely caused by the persistent head trauma of life in football’s trenches.

Strzelczyk (pronounced STRELL-zick) is the fourth former National Football League player to have been found post-mortem to have had a condition similar to that generally found only in boxers with dementia or people in their 80s. The diagnosis was made by Dr. Bennet Omalu, a neuropathologist at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine. In the past five years, he has found similar damage in the brains of the former N.F.L. players Mike Webster, Terry Long and Andre Waters. The finding will add to the growing evidence that longtime football players, particularly linemen, might endure hidden brain trauma that is only now becoming recognized.

“This is irreversible brain damage,” Omalu said. “It’s most likely caused by concussions sustained on the football field.”

Dr. Ronald Hamilton of the University of Pittsburgh and Dr. Kenneth Fallon of West Virginia University confirmed Omalu’s findings of chronic traumatic encephalopathy, a condition evidenced by neurofibrillary tangles in the brain’s cortex, which can cause memory loss, depression and eventually Alzheimer’s disease-like dementia. “This is extremely abnormal in a 36-year-old,” Hamilton said. “If I didn’t know anything about this case and I looked at the slides, I would have asked, ‘Was this patient a boxer?’ ”

The discovery of a fourth player with chronic traumatic encephalopathy will most likely be discussed when N.F.L. officials and medical personnel meet in Chicago on Tuesday for an unprecedented conference regarding concussion management. The league and its players association have consistently played down findings on individual players like Strzelczyk as anecdotal, and widespread survey research of retired players with depression and early Alzheimer’s disease as of insufficient scientific rigor.

The N.F.L. spokesman Greg Aiello said that the league had no comment on the Strzelczyk findings. Gene Upshaw, executive director of the N.F.L. Players Association, did not respond to telephone messages seeking comment.

Strzelczyk, 6 feet 6 inches and 300 pounds, was a monstrous presence on the Steelers’ offensive line from 1990-98. He was known for his friendly, banjo-playing spirit and gluttony for combat. He spiraled downward after retirement, however, enduring a divorce and dabbling with steroid-like substances, and soon before his death complained of depression and hearing voices from what he called “the evil ones.” He was experiencing an apparent breakdown the morning of Sept. 30, 2004, when, during a 40-mile high-speed police chase in central New York, his pickup truck collided with a tractor-trailer and exploded, killing him instantly.

Largely forgotten, Strzelczyk’s case was recalled earlier this year by Dr. Julian Bailes, the chairman of the department of neurosurgery at West Virginia University and the Steelers’ team neurosurgeon during Strzelczyk’s career. (Bailes is also the medical director of the University of North Carolina’s Center for the Study of Retired Athletes and has co-authored several prominent papers identifying links between concussions and later-life emotional and cognitive problems.) Bailes suggested to Omalu that Strzelczyk’s brain tissue might be preserved at the local coroner’s office, a hunch that proved correct.

Mary Strzelczyk granted permission to Omalu and his unlikely colleague, the former professional wrestler Christopher Nowinski, to examine her son’s brain for signs of chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Nowinski, a former Harvard football player who retired from wrestling because of repeated concussions in both sports, has become a prominent figure in the field after spearheading the discovery earlier this year of C.T.E. inside the brain of Andre Waters, the former Philadelphia Eagles defensive back who committed suicide last November at age 44.

Tests for C.T.E., which cannot be performed on a living person other than through an intrusive tissue biopsy, confirmed the condition in Strzelczyk two weeks ago. Omalu and Nowinski visited Mary Strzelczyk’s home near Buffalo on Wednesday to discuss the family’s psychological history as well as any experiences Justin might have had with head trauma in and out of sports. Mary Strzelczyk did not recall her son’s having any concussions in high school, college or the N.F.L., and published Steelers injury reports indicated none as well.

Omalu remained confident that the damage was caused by concussions Strzelczyk might not have reported because — like many players of that era — he did not know what a concussion was or did not want to appear weak. Omalu also said that it could have developed from what he called “subconcussive impacts,” more routine blows to the head that linemen repeatedly endure.

“Could there be another cause? Not to my knowledge,” said Bailes, adding that Strzelczyk’s car crash could not have caused the C.T.E. tangles. Bailes also said that bipolar disorder, signs of which Strzelczyk appeared to be increasingly exhibiting in the months before his death, would not be caused, but perhaps could be exacerbated, by the encephalopathy.

Omalu and Bailes said Strzelczyk’s diagnosis is particularly notable because the condition manifested itself when he was in his mid-30s. The other players were 44 to 50 — several decades younger than what would be considered normal for their conditions — when they died: Long and Waters by suicide and Webster of a heart attack amid significant psychological problems.

Two months ago, Omalu examined the brain tissue of one other deceased player, the former Denver Broncos running back Damien Nash, who died in February at 24 after collapsing following a charity basketball game. (A Broncos spokesman said that the cause of death has yet to be identified.) Omalu said he was not surprised that Nash showed no evidence of C.T.E. because the condition could almost certainly not develop in someone that young. “This is a progressive disease,” he said.

Omalu and Nowinski said they were investigating several other cases of N.F.L. players who have recently died. They said some requests to examine players’ brain tissue have been either denied by families or made impossible because samples were destroyed.

Bailes, Nowinski and Omalu said that they were forming an organization, the Sports Legacy Institute, to help formalize the process of approaching families and conducting research. Nowinski said the nonprofit program, which will be housed at a university to be determined and will examine the overall safety of sports, would have an immediate emphasis on exploring brain trauma through cases like Strzelczyk’s. Published research has suggested that genetics can play a role in the effects of concussion on different people.

“We want to get a idea of risks of concussions and how widespread chronic traumatic encephalopathy is in former football players,” Nowinski said. “We are confident there are more cases out there in more sports.”

Mary Strzelczyk said she agreed to Omalu’s and Nowinski’s requests because she wanted to better understand the conditions under which her son died. Looking at the C.T.E. tangles on a computer screen on Wednesday, she said they would be “a piece of the puzzle” she is eager to complete for herself and perhaps others.

“I’m interested for me and for other mothers,” she said. “If some good can come of this, that’s it. Maybe some young football player out there will see this and be saved the trouble.”

A correction was made on June 16, 2007

:

A sports article yesterday about Justin Strzelczyk, a former National Football League player who was found post-mortem to have had early signs of brain damage that experts said was most likely caused by football concussions, misidentified the medical institution where Bennet Omalu, the doctor who made the diagnosis, is a clinical instructor of neuropathology. It is the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, not the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center.

When we learn of a mistake, we acknowledge it with a correction. If you spot an error, please let us know at [email protected] more

Pat Sullivan

Daniel Te’o-Nesheim

On behalf of our entire family, I would like to thank everyone for all the love and support shown to us since the passing of our beloved Daniel Te’o-Nesheim. Your prayers and various acts of kindness throughout the years continue to help us find peace and some sense of closure given that he was called home so suddenly. We also want to thank his lawyer Samuel Katz and his firm Athlaw LLP, his agent Eric Kaufman, Bobby Abdolmohammadi of Boston University, and Lisa McHale with the Concussion Legacy Foundation. We admire the guidance of the teams at the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank and the Concussion Legacy Foundation to help us navigate systems to find more in-depth answers and help us carry on Daniel’s legacy.

Daniel was born June 12, 1987 in American Samoa. He was always an energetic, humble boy with a smile that could lighten any mood. When he was 3, we moved to Seattle where he began playing soccer, baseball and basketball. When he was 12, we lost our dear father and our whole world changed.

In 2001, Daniel was given the opportunity to attend Hawaii Preparatory Academy (HPA), a boarding school in Hawaii. He flourished and continued to play basketball, baseball, and found a new love for football. Many times, you would find him in the weight room after hours training.

In 2005, Daniel graduated and was blessed with a D1 scholarship to the University of Washington. He was ecstatic to return to our father’s hometown and continue his football career where he chose to study art and photography. Daniel flew home to Hawaii as much as possible and visited his family and friends where he would continue to train and spend quality time with us.

On December 5, 2009, Daniel plowed his way into the UW record book by setting the school’s all-time sacks record with 30.

“If anyone on our football team or anyone in this conference deserves a record, it’s Daniel Te’o-Nesheim,” said then-UW head coach Sarkisian. “There is not a guy who practices harder.”

In 2010, Daniel was drafted by the Philadelphia Eagles in the 3rd round with the 86th overall pick. His lifetime dream came true. He continued this dream for five years, ending his career with the Tampa Bay Buccaneers in 2015. Daniel traveled home less during this time and after his career ended, he decided to return home for good. From 2015 to 2017, Daniel coached football back at HPA and he enjoyed every minute.

Seeing him more on a regular basis, we noticed Daniel complained daily of headaches and excruciating pain in various parts of his body. He forgot crucial commitments and unintentionally blew off friends. He would go to the grocery store with a list in his mind and only come back with two out of five things but felt he had purchased everything on his list. We thought this was just him getting sidetracked and harmless forgetfulness.

Although we occasionally confronted him about the differences we saw, he refused to seek help and would defiantly insist that everything was fine. He brushed off requests to see a doctor or he would forget about appointments, even with reminders.

Daniel’s untimely passing on October 29th, 2017 was like déjà vu to when our father passed. Both times were without warning and neither allowed any of us to say goodbye. However, this time around, I pledged to step up to find out why someone so young, vibrant, and essentially in good physical condition had gone so soon. More importantly, I will honor my brother and ensure that his legacy lives on through raising awareness about the causes, signs, symptoms, and impacts of concussions.

Even though he was the youngest sibling, Daniel tried to shield us from so much of his pain and suffering because he did not want to worry us with his struggles from football. It wasn’t until his passing that we learned about the grueling pain he endured from his years playing the game he loved. We now know about steps he took to get help with the physical, emotional, and neuropsychological agony he was facing every day. We learned after his passing that Daniel reached out to a former colleague four months before his passing about issues he was dealing with. Daniel knew this athlete was going through much of the same issues and was suffering from many of the same disabling symptoms. Daniel reached out for help. Thankfully, his friend introduced Daniel to Sam Katz of Athlaw LLP.

In early October 2017, Daniel traveled to Texas for a physical with the NFL. In true “protector” fashion, Daniel simply told us he had to “go finish some NFL things.” Unfortunately, the NFL scheduled Daniel’s neuropsychological and neurological tests for a different date and were unable to evaluate Daniel’s cognitive issues during his physical. This made it impossible for Daniel to be fully mentally and physically evaluated, despite Sam telling him how important it was for him to attend both appointments and get fully evaluated. Even amid his struggles, Daniel always put the kids he coached first because he wanted to inspire others. That’s just who Daniel was. Instead of going for his necessary appointments, Daniel showed up to a football game and inspired a youth team.

When he returned home, he said the appointment in Texas went well. The doctor said he had the ankle arthritis of a 70-year-old, degeneration in both of his knees, neck pain with movements, radiating pain in his back, shoulder pain that caused him difficulty with activities, among other substantial functional disabilities. Daniel mentioned that he may need to go back but never mentioned any more specifics beyond that.

The morning after his death, we were trying to find answers about what happened to Daniel. We recovered his paperwork from various medical exam records during the NFL. It looked like a college textbook. We read through these painful visits, unknown surgeries, and journal entries of experiences during the NFL. We saw daily reminders on his cell phone for simple, everyday tasks. We then realized the depth of his pain. When we found notes from Sam Katz, we reached out to Athlaw LLP and started to piece together the many parts of Daniel’s life that he kept to himself.

With Sam’s help, we were able to learn Daniel missed the neurology and neuropsychology portion of testing. Sam also let us know about the amazing work being done at Boston University by Dr. McKee and Dr. Jesse Mez. We were also made aware of the work by Dr. Chris Nowinski and the team at the Concussion Legacy Foundation and that we had the option of donating Daniel’s brain to Boston University’s Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy Center. Due to Daniel’s sudden death and him being so young, I called the medical examiner and insisted they perform the autopsy immediately as it was a very rare incident and we needed answers immediately. When my mother and I agreed to donation, I contacted the medical examiner at Kona Community Hospital and explained what we were trying to accomplish. The medical examiner was honored to help and performed the autopsy on October 30, 2017.

Daniel’s agent Eric Kaufman helped us realize Daniel was experiencing very major symptoms associated with CTE during his final years in the league. I wish I had known more about this degenerating disease that stems from repetitive head injuries so I would have been able to help Daniel seek the help he needed. Looking through and filling out surveys from BU, I began to see he had almost all the symptoms of CTE.

In the aftermath, knowing what we do now, we can look back and see the signs that we missed and were untreated for so long. We missed mental and behavioral changes from Daniel’s years of playing high school, through college for the University of Washington, and in the NFL, that are now obvious because we know more about the signs and symptoms of what he and many former players have gone through. Daniel loved football, and he gave his life to the sport, but a diagnosis and cure must be found for this terrible disease!

As we continue to face the realities of this life without Daniel, we are committed to furthering his legacy, celebrating his love of football but recognizing the risks it poses and trauma that can result from it, which contributed to his sudden death at an early age. Our family is committed to doing our part to raise awareness about concussions and CTE, including taking steps to protect our athletes, educating them on how to recognize signs and symptoms if affected, as well as developing a stronger network of support for struggling athletes and their families. Together with experts in the field, we join the ranks of affected families and are now passionate about making sure no one else has to go through the pain of losing a loved one to this disease as we did.

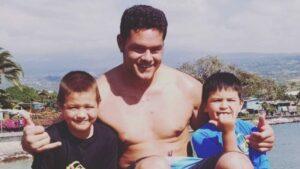

Our family misses Daniel tremendously. Daniel was like a big brother to his niece and nephews and his loss has hit them hard. We are comforted in knowing Daniel’s name and legacy lives on, as we have become advocates for concussion awareness, support, and research and have also created an award named after Daniel at HPA. Daniel loved the game of football and his unique love for inspiring children is why we created The Coach Daniel Te’o-Nesheim Award to acknowledge a senior football player who is recognized by coaches, staff, teammates, and peers as exhibiting the rare combination of qualities that made him special:

-Unrelenting effort

-Dedication

-Preparedness

-Quality execution

-The highest respect for competition

The award goes to a player who inspires teammates to elevate themselves, who is respected as a leader on and off the field, and who has a clear and honest love for HPA. Through this award, Daniel will live on through the youth he loved to inspire even during his darkest times.