Bill Troup

Max Tuerk

Max Tuerk was a force to be reckoned with from birth: he came into the world a whopping 9 pounds, 8 ounces, ready to make his mark. His massive smile lit up his face. He was gregarious and outgoing. He was never hesitant nor fearful and jumped into new experiences with excitement and an eagerness for adventure. Max loved to be around people and had many friends. He was known for his warmth, loyalty, and fun-loving spirit. He had a personality to match his size.

Under the smile and playful, adventurous spirit, was a will of steel. He knew what he wanted and was relentless in pursuing his goals. In middle school, he secretly carved “USC – NFL – HOF” onto his desk. He was able to achieve two of those lofty goals during his short life.

Max was very close with his siblings and was unquestionably the leader of the Tuerk squad. He was sometimes affectionately called “Officer Max” because he always kept Drake, Abby, and Natalie in line! He was fiercely loyal and was their mentor and protector. He always encouraged his siblings, especially in sports. He loved to watch a fierce competition as much as he loved to participate in one – once offering Natalie $5.00 if she could get a red card in soccer! Max had special relationships with his parents as well. He bonded with his dad over sports, competition, grilling, and beer. He and I enjoyed travel, adventures, and playing games together. As anyone who knew Max can attest, he loved to eat and appreciated good food. It was a true pleasure to cook for him and we shared many wonderful meals as a family.

Beyond his determination, Max’s defining characteristic was his loyalty. He was devoted to his family, friends, teammates, and coaches. He loved football, not for fame or for money, but for the camaraderie and bonds he established with his teammates, whom he considered brothers. He had zero tolerance for negativity or backbiting, which he would quickly squelch. He never complained about coaches, playing time, or teammates. He was known to stand up for the underdog on the team. This is one of Max’s most important legacies: every time we find ourselves gossiping or criticizing, we remember Max and pause. We want to live up to the high standards he set.

Max loved sports from an early age – any sport, any time. He just loved to be part of a team and to be with his friends. He started out in taekwondo, soccer, and baseball, but found his true love when he began playing tackle football in the 4th grade. Max was the ultimate competitor. He never took a play off. He gave every bit of himself to his game and inspired those around him to do the same. He was a natural leader who inspired confidence in teammates and coaches.

Football came to dominate Max’s life in high school, and it became clear he was blessed with great talent to go with that amazing determination and work ethic. Max helped lead his Santa Margarita High School Eagles to win the State Championship his senior year, playing both offensive tackle and defensive end. He was selected as an Army All-American his senior year and received 30 D-I football scholarship offers. Max signed with USC, ticking the first item off the list he carved into his desk years before.

Max made history at USC as the first freshman to start at left tackle. Max’s first game at left tackle was also coach Clay Helton’s first game as offensive coordinator, and it was a big one against Oregon in the Coliseum. Coach Helton was a bit nervous before the game and asked Max, “Are you going to be OK?” Max smiled and assured him, “I’ve got you, Coach.” There Max was inspiring others, as usual.

Throughout his USC career, Max played all five offensive line positions. He was admired and respected by his teammates and was twice voted team captain. Although there was a great deal of turmoil at USC during his time there, including multiple head coaching changes and a different offensive line coach each year, Max loved USC and was a true Trojan. He made wonderful friends, joined a fraternity, and fell in love. Unfortunately, Max’s senior season was cut short when he tore his ACL against Washington on October 8, 2015. Not to be deterred from fulfilling his dream to continue in football, Max decided to leave USC to prepare for the NFL draft. Despite his injury, Max was selected by the San Diego Chargers with the 66th overall pick in the 2016 NFL draft. The second item on his list was checked off.

We first noticed changes in Max’s behavior after the draft. Normally outgoing and gregarious, Max began to isolate himself and stopped communicating with his family. This concern intensified once Max moved to San Diego with the Chargers. He became extremely paranoid and suspicious, and his behavior turned increasingly erratic. The move from the camaraderie he had known and loved his whole life to the world of professional sports was a challenging transition. He was convinced that members of the Chargers were trying to sabotage him and his paranoia soon extended to his family. He began to believe we were collaborating with his enemies to harm him.

This behavior was extreme, alarming, and confusing. Initially, we worried drug use was causing this erratic behavior. But it soon became clear Max was experiencing a mental health crisis. Max’s mental illness led him to make choices that were extremely detrimental to his future. To make matters worse, he had no insight into the fact he was ill, which absolutely devastated us. We wanted nothing more than for Max to get the help he so desperately needed, but he was unable to recognize he needed help. Instead, he thought we were trying to harm him. All those years of playing through the pain and refusing to acknowledge any weakness had made it virtually impossible for Max to ask for or accept help.

He continued to isolate himself from his family, friends, and support system. In this altered state of mind and in isolation, he sought alternatives to enhance his chances of success in the NFL, leading to his choice to take performance enhancing drugs. This was completely out of character for Max and led to his suspension by the Chargers before his second season. At this time, Max was persuaded to see a psychiatrist, who prescribed Max with antipsychotic medication. The medicine did seem to help Max for a time. He was dropped to the Chargers practice squad after his suspension but was picked up by the Arizona Cardinals and looked to make a fresh start. But the second season unfolded much the same as the first. Max was simply not the same physically or mentally and at some point, stopped taking his prescribed medication. He was dropped by the Cardinals after the 2017 season.

Max returned home to southern California and tried to remake his life. His symptoms made it difficult for him to maintain a job – he struggled with hallucinations, psychosis, and extreme depression. Although still lacking insight into his condition, he was aware something was seriously wrong and made every effort to take care of himself. He believed he could fix what was going on in his brain and was extremely disciplined about his food intake and exercise. He had always been able to take care of things on his own. Why should this be different?

Max’s symptoms became increasingly severe and could not be managed without medication. Max had several serious incidents and was hospitalized twice. The second hospitalization was triggered by threats of violence to his family. Max was not violent before this incident and had always been considered a gentle giant. This was devastating for all of us, but particularly for Max. He could no longer recognize himself. He had been the protector of family and friends his whole life. This was not who he was. Finally, Max gained insight into his illness and voluntarily accepted treatment.

Max approached treatment as he approached everything in his life, with steely determination. He was going to have the life he dreamed of and deserved, and we were filled with admiration watching him fight. He had to deal with paranoia, psychosis, hallucinations, and a depression he described as the deepest darkness he had ever faced. He also dealt with mental fog, headaches, and what we later found out to be cardiac symptoms. He was battling a mental illness while watching everything he had ever dreamed of evaporate before his eyes. Max’s pain was unbearable and excruciating for our family. The mental demons Max faced were wreaking havoc on him, but he puffed out his chest and “fought on.” He never complained or despaired. He believed he would be able to get his life back.

Max managed his mental health and maximized his new reality. He was working part time, going on daily hikes with me, eating, exercising, and taking care of himself. We know he was struggling with all of this, but he was very stoic and never let on that he was in pain.

On June 20, 2020, Greg, Max, and I took a beautiful hike together. Max collapsed on the trail. Paramedics were called and helicopters arrived, but Max died on the trail with us. We learned after his death that he had an undiagnosed cardiac condition known as cardiomegaly, or an enlarged heart, which caused his death. His death was a tragic loss and has left a gaping hole in our lives. But we feel comforted that he was in a beautiful place doing something he loved, with the people who loved him most in the world.

We were looking for answers in the dark days of Max’s mental illness – why was this happening to this proud and capable young man? We knew something was terribly wrong with his brain but there was no help to be found. No one understood what was happening and no one could help Max when he did not want help. We suspected Max had CTE and Greg reached out to Dr. Chris Nowinski at the Concussion Legacy Foundation for help in these dark days. Chris provided warm understanding and helped us to feel a bit less alone.

When Max died unexpectedly on that trail, one of our first calls was to Chris to arrange for Max’s brain donation. We hoped and prayed we could get to the bottom of what had happened to our beautiful, strong boy. Max’s brain was studied by Dr. Ann McKee, and he was diagnosed with stage 1 (of 4) CTE. In addition, his brain showed significant white matter damage and there was a cavum septum pellucidum between the hemispheres of his brain. His brain had been damaged by all the years of impact he sustained playing the sport he loved. We were not surprised as we knew something was dreadfully wrong in Max’s brain.

Max never had a diagnosed concussion, but there is no doubt he had several. Sometimes after a particularly tough game, he would seem unusually sad, quiet, and aloof. Of course, he never acknowledged that anything was wrong or he was in pain. Once he was in the NFL, he had debilitating headaches and would require darkness and silence. But more important than these probable concussions, he experienced nonconcussive head impacts repeatedly from the age of nine. As a lineman who played offense and defense until reaching college, Max’s brain absorbed hit after hit, setting the stage for the disease that would take everything from him and take him from us.

Football was Max’s life. But that love cannot begin to compare with the pain and suffering he experienced at the end of his life. It was absolute hell physically and emotionally. And we now know it was all preventable. He could have played the sport he loved in a much safer way. He could have played flag football until he got to high school, saving his brain from the countless hits he absorbed between fourth and ninth grade.

Max and I hiked daily in his final months of life, and I feel very connected to him each time I walk on “our trail.” One day when I was hiking, I felt Max speaking to me very loudly – my determined boy had something to say. I dictated these words on the trail; I have never written a poem in my life, and I am certain this came directly from Max and was meant to be read and to make a difference:

They are born with the heart of a warrior.

That heart swells with the words of those around them:

“Play through the pain”

“Take one for your team”

“Never give up”

And their brain responds.

This is who they are. They are buoyed by the words of those around them:

“You’re a leader”

“You’re so strong”

“Never show weakness”

“You’re a beast”

You understand that you cannot stop to answer the call of pain. That would be a weakness and above all, you cannot show a weakness.

Your brain takes this in and adapts.

They make you a hero. A star. Everyone knows your name.

It creeps in slowly.

Headaches that won’t go away. The confusion. The blackouts. How can it be there? That doesn’t happen to you.

You continue to play, but your shimmer slowly starts to dull.

You understand there’s a tangle inside your brain. Something isn’t right. But that same strength of character that led you to excel will not allow you to ask for help.

Eventually, the monster inside your brain robs you of everything. You can no longer do what you love. You can no longer trust those around you. You are in so much physical and mental pain.

You are so very, very alone.

Your suffering is immense.

Everyone who made you into a hero are quick to turn away.

The fame is ephemeral. And the cost was immense.

The very sense of self at its core is shattered from the pinnacles of success to the depths of despair.

To be so capable and successful and to be reduced in so many ways. It’s just intolerable.

The monster.

Tommy Vaughn

A historic career

Tommy Vaughn grew up in Troy, Ohio as the oldest of five children and shouldered the responsibility that many eldest siblings are dealt. Vaughn had to help care for his young siblings but still found time to play sports with neighborhood friends. He started playing tackle football in local parks when he was seven years old.

Along with football, Vaughn lettered in baseball and basketball at Troy High School. While he received scholarship offers for all three sports, he followed his love of football and accepted a scholarship to Iowa State University. There, he would become the Iowa State Athlete of the Year in 1963 and an Academic All-American in 1964.

For his athletic accomplishments, Vaughn would later be inducted into the respective Hall of Fames for The City of Troy, Iowa State University, and Troy High School.

After his decorated college career ended, Vaughn was drafted by the Detroit Lions and married his college sweetheart, Cynthia, in 1965. They had two children, Terrace and Kristal.

Vaughn never missed a game in his seven-year career in the NFL. During those seven years, there were three times he woke up in a hospital room after being knocked out in a game. After the third knockout, a doctor warned him of the dangers of continuing to play if he suffered more concussions. In 1972, Vaughn chose his health and his family over football and retired at the age of 29.

Life after football

Growing up, Vaughn was raised to be humble. Despite being an NFL star, Kristal Vaughn says she never saw her dad think he was better than anyone else. He always made time to sign autographs for young fans and his bright personality followed him wherever he went.

When she speaks about her dad, she remembers him far less for his football accolades and much more for his kindness and intellect.

“He was an intelligent, happy, nerd,” said Kristal. “He was like Sheldon from The Big Bang Theory, but athletic.”

Vaughn enjoyed a robust life after football. He acted in the movie Paper Lion, earned his master’s degree, was a general manager at the Chrysler Corporation in Detroit, the President of Union National Bank of Chicago, and a high school teacher. Despite his success in business and education, Vaughn couldn’t stay away from the game for long.

“He loved teaching the game,” said Kristal. “My dad was the most giving, caring person in the world.”

He became an assistant coach of the World Football League’s Detroit Wheels and then later for his alma mater at Iowa State University, the University of Wyoming, the University of Missouri, and Arizona State University.

Later, Kristal heard from many of Vaughn’s former players and students. Many of them told her about how coach or Mr. Vaughn never gave up on them.

Much to his dismay, Vaughn often worked long hours in coaching. After a long day, Vaughn often woke his children up to bake pies. The activity served two purposes: squeeze in precious family time and satisfy his legendary sweet tooth.

“I never got to know my real daddy”

For all the wonderful moments the Vaughns shared together, their household was not always a safe place.

Shortly after Vaughn retired from the NFL, his family noticed him become more anxious. Kristal remembers her father’s anxiety first manifesting into violent outbursts. She says her father always had a soft spot for animals, but he began taking his anger out on the family dog.

As Vaughn’s symptoms progressed, Kristal says his anxiety and agitation led to physical violence toward her mother and siblings.

When Vaughn moved the family from Detroit to take a coaching job at ISU, Kristal says her parents separated for six months because Vaughn didn’t resemble the man her mom Cynthia fell in love with.

The type of man Cynthia once knew was one their children would never get to meet.

“I never got to know my real daddy,” said Kristal. “And that’s not fair.”

When the family was in Iowa, Vaughn was prescribed medications to help manage his symptoms. Terrace caught on that his father was taking “puppy uppers” and “doggy downers” to regulate his emotions and behaviors. He told his sister to remind their father to take his pills if he was acting out. Tommy Vaughn was later diagnosed with bipolar disorder.

To cope and to protect herself, Kristal learned from a young age to remove herself from the situation whenever things at home became hostile. A self-described nerd herself, Kristal found refuge in books at her local library.

“I learned to not try to soften it,” said Kristal. “Don’t get involved with it, let them have their moment. Things will calm down.”

In 1985, Vaughn took a coaching job at Arizona State University. While in Arizona, Vaughn’s short-term memory began to decline. Kristal remembers her father would frequently repeat himself but would deny the repetition when anyone brought it to his attention.

Through her role as a social worker at a rehabilitation center that served brain injury patients, Cynthia gained a better understanding of how to work with her husband’s symptoms. She encouraged him to begin seeing a psychiatrist in Scottsdale who prescribed better medications to help stabilize Vaughn’s behavior.

Medications helped, but only to a point. Vaughn’s verbal filter disappeared over time, leading him to say vulgar or hurtful things to those around him, only to forget he said them minutes later. This pattern led his wife and children to follow the motto of, “if he didn’t remember, it didn’t happen and move on.”

As Vaughn aged, his mood swings and behavioral changes took a turn for the worse. In his late 60’s, he was the lieutenant governor of the Optimist Club youth program in Arizona. Every week, Optimist Club leadership met for breakfast at a local diner. One day, Vaughn misinterpreted a comment a waitress made and threatened her. Management asked Vaughn to leave and to never come back.

Vaughn suffered from panic attacks for much of his post-football life. At first, the episodes occurred every few months. By 2013, the attacks became weekly occurrences, usually triggered by trivial matters.

In 2015, Cynthia decided to bring Vaughn to the Barrow Institute in Phoenix, Arizona where he was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease.

Vaughn had been on a progressive downslide for years, but his football career and extensive concussion history was never discussed as a culprit until he reached his early 70’s. Vaughn began to connect the dots between the repetitive head trauma he endured throughout his football career and the symptoms he struggled with for much of his life. He later told his family he wanted his brain to be donated to the UNITE Brain Bank for CTE research.

As things worsened, Vaughn’s family desperately needed support to help manage his declining condition. That support came from an NFL contemporary of Vaughn’s.

“I have to be grateful for the 88 Plan,” said Kristal. “There is help out there. You’re not by yourself.”

The 88 Plan is named after Hall of Fame tight end and Legacy Donor John Mackey, who wore number 88 in the NFL and played in the league with Vaughn. Mackey died in 2011 after a long battle with what was eventually diagnosed as CTE. His public struggle with the disease led to the 88 Plan, which provides $88,000 a year for families of former players living with dementia.

Eight months after starting to receive 88 Plan benefits, Vaughn died at age 77. His family fulfilled his wish to have his brain studied, and Brain Bank researchers posthumously diagnosed him with Stage 3 (of 4) CTE.

“Do you guys get this?”

After she learned her father had CTE and not Alzheimer’s, Kristal was immediately taken back to a traumatic memory.

Kristal has a history with traumatic brain injury herself and suffers occasional seizures as a result. Once, in the last years of her father’s life, she was coming out of a seizure, laying down on the floor. She came to as her dad was pounding her head into the ground, screaming at her to wake up. In the chaos, Vaughn got frustrated at Cynthia and struck her as well.

“30 years ago, he would never have done that,” said Kristal. “He had the biggest, most beautiful heart.”

To other families with loved ones affected by possible CTE, Kristal wants to ensure they never abandon their loved one, but to also always prioritize their own safety. She says the lesson she learned as a child – to remove herself and to not engage with her father when he became aggressive – is vital to caregiving for someone with potential CTE. In her experience, her father would always calm down if given enough time.

She also urges those in power in the NFL to take player welfare more seriously and consider how a former player’s symptoms of CTE can devastate a family.

“I want to ask them, ‘Do you guys get this?’”

Despite the tremendous adversity she and her family have faced, Kristal retains an eternal sense of optimism. Her lasting message to other CTE families is one of resilience.

“We made it,” said Kristal. “We survived this. You can too.”

If you are being physically hurt by a family member or loved one, know it is not your fault and there is help available. For anonymous, confidential help, 24/7, please call the National Domestic Violence Hotline at 1-800-799-7233 (SAFE).

Are you or someone you know struggling with symptoms of suspected CTE? We support patients and families through the CLF HelpLine, providing personalized help to those struggling with the outcomes of brain injury. Submit your request today and a dedicated member of the Concussion Legacy Foundation team will be happy to assist you. Click here to support the CLF HelpLine.

Edward Voytek

Frank Wainright

Fulton Walker

Before Bo Jackson, Deion Sanders, Tim Tebow, or Kyler Murray blurred the lines between professional football and baseball, there was Fulton Walker. Walker grew up in Martinsburg, West Virginia and started playing tackle football at eight years old. He raced past defenders in youth football and shined on the baseball diamond. His exploits became the stuff of legend. Walker’s son Kevin was born when Fulton was in high school, so Kevin was well versed on his dad’s athletic prowess by the time he grew up.

“I was sitting in one of my P.E. classes and the teacher tells me how my dad was the best athlete to ever come out of West Virginia,” Kevin said. “He was saying, ‘I watched him play a baseball game one day and rob a home run and then that night run a punt back.’”

Walker was a four-sport letterman for Martinsburg High School and a key player at home as well. He would rush back home from games and track meets to mow his family’s yard and to split wood for a fire.

After he graduated from Martinsburg, the Pittsburgh Pirates selected Walker in the 25th round of the 1977 MLB Draft. He opted instead to attend West Virginia University, where he watched many football games as a kid and where he could play both football and baseball.

Walker became one of the first Black athletes to play for the WVU baseball team. In football, he played running back and returned punts for the Mountaineers as a freshman. He made headlines his first season by returning a punt 88 yards for a touchdown against Boston College.

He switched to defense his junior season and held a larger role on the team. Coach Don Nehlen arrived at WVU for Walker’s senior season and immediately counted Walker as one of his favorite players.

“You have certain guys on your football team that really enjoy the game – it doesn’t matter if it’s Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday or Saturday, they like to play and Fulton was one of those guys,” Nehlen would later say. “You’d go out there on Tuesday and he was grinning and then on Wednesday he was grinning. He was very popular on our football team.”

Walker’s popularity was not contained to the Mountaineers locker room. Kevin Walker saw his dad get stopped by friends and strangers his whole life. Fulton could not go to a cookout or a grocery store without someone wanting to stop and chat with the local legend.

“He was always pulled one way or another for conversation and one minute turned into 30 minutes and we’d be hours late for things. And he would always stop. He always had time,” Kevin said. “He’d never act like he was Superman. You know, he was just a regular old guy from a little country town.”

Walker’s senior season at WVU was a huge success. He finished with 86 tackles and two interceptions for the team in a season that would be credited with turning the football program around. The Miami Dolphins selected Walker in the 6th round of the 1981 NFL Draft.

His cool, upbeat, down-to-earth personality made him just as much of a locker room favorite in Miami as he was in Morgantown. Walker’s next-door neighbor in Miami was Dolphins star quarterback Dan Marino. Walker and Marino bonded over the rivalry between their alma maters, Walker’s West Virginia and Marino’s Pittsburgh, which is serendipitously known as “The Backyard Brawl.”

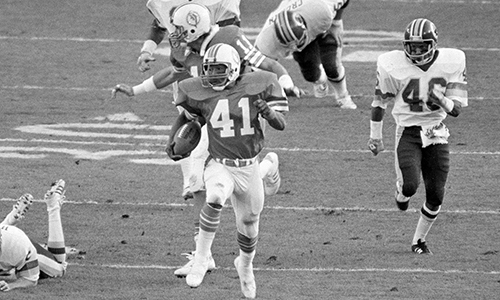

Walker played five seasons with the Dolphins as a cornerback and a special teams ace. His career highlight came when he became the first player to return a kickoff for a touchdown in a Super Bowl when he sprinted 98 yards for a touchdown to give the Dolphins a 17-10 lead in Super Bowl XVII in 1983.

No one could catch Fulton Walker that day, or most days for that matter. But Kevin did. Once.

“We were walking to my aunt’s house and he was like, ‘Man you wanna race?’ and I said let’s do it,” Kevin said. “And we ran pole to pole and I beat him.”

Walker tried to put an asterisk on the defeat by claiming he did not have the right footwear for the occasion. But 13-year-old Kevin let everyone in his junior league baseball dugout know he beat the Super Bowl record-holder.

After two more injury-riddled seasons with the Los Angeles Raiders, Fulton Walker retired from football in 1986. Playing primarily special teams, Walker only saw the field for a handful of plays each game. But the impacts he was involved in on kick and punt returns count among the fastest and most violent in the sport. After football, Walker had his ankles fused, his vertebrae fused, and took more than a dozen pills a day to alleviate pain in his neck and to help him sleep.

“His injuries, you’d think it was from motorcycle wrecks or something. But he just played football. So yeah, you’re tough. But your body can only take so much,” Kevin said.

With football behind him, Walker went back to WVU to earn his master’s degree in Industrial Safety. Kevin says Walker was extremely sharp and could handle a very large workload. For years he managed a trucking company in West Virginia and then became a teacher and coached football and baseball back at Martinsburg High. He satisfied his itch to stay physically active by playing golf and softball as often as he could.

Walker then started to struggle with his memory. He would forget where he put his keys, leave his car running, go to the store and forget why he went by the time he got there, and repeat himself in conversations. These short-term memory issues affected his ability to work. He would forget how to use certain computer systems he mastered the week before. Eventually, the state of West Virginia determined he needed to go on full disability.

The memory battles caused Walker to get frustrated with himself. He took his frustrations out on others and slipped into depression.

“My problem is I can’t multi-task. I can’t get my brain full of stuff because it puts me in a place of confusion,” Walker said in an interview with Katherine Cobb in September 2016. “Stuff in the present I can have problems with, but stuff in the past, I still have good recollection. I have to write things down now, so I remember. It is what we guys have been going through but we didn’t understand what was going on. It’s been frustrating and overwhelming sometimes.”

When Kevin saw his dad almost daily, his decline was less noticeable. But when he moved away to North Carolina and saw his dad less frequently he noticed how steep his fall was. Kevin knew his dad needed help and set up appointments for neurological testing in Orlando and Atlanta. Those tests showed Walker suffered from dementia, which qualified him for benefits from the NFL’s “88 Plan,” named after Hall of Fame tight end and CLF Legacy Donor John Mackey.

On the night of October 11, 2016, Kevin called his dad to let him know he would need to switch cars with him for Kevin’s upcoming work trip. Kevin arrived the next morning and grabbed the keys his dad had left out on the counter. He chose to let his dad sleep rather than to say goodbye. As Kevin was driving home from the meeting later that day, he received a call that Fulton was being rushed to the hospital.

Kevin drove to meet his dad at the hospital, but it was too late. Fulton Walker was pronounced dead on October 12, 2016 at 58 years old. He died from a heart attack.

Walker’s funeral in Martinsburg was full of testaments to his humility, generosity, and ability to make those around him feel like they, not him, were the Super Bowl record holder in a conversation.

Kevin and the family decided to donate his brain to the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank after his death to see if his cognitive and emotional problems could be attributed to Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE). Dr. Ann McKee, Director of the Brain Bank, diagnosed Walker with mild CTE in his dorsolateral frontal and temporal cortices.

Fulton Walker loved football too much for the family to hold ill will against the sport for its role in his CTE. Instead, Kevin believes his dad would have opted to play flag football as a kid and would advocate for the next generation to do so as well. Kevin points to Barry Sanders’ training in flag football to increase his elusiveness to show how playing flag football improves ballcarriers’ open-field skills.

Kevin knows that playing pro football when his father did and now are two different financial realities. He thinks today’s NFL players have the liberty of shortening their careers and protecting themselves in a way his father’s generation did not.

To other children who have parents that spent a life in contact sports and who might be at risk for CTE, Kevin urges you to stay aware, and take action to get help sooner than later if you see signs like mood swings or forgetfulness.

Kevin will always remember his dad for his work-ethic, humility, laid-back personality, and as a pioneer for two sport athletes.

Are you or someone you know struggling with lingering concussion symptoms or possible Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE)? We support patients and families through the CLF HelpLine, providing personalized help to those struggling with the outcomes of brain injury. Submit your request today and a dedicated member of the Concussion Legacy Foundation team will be happy to assist you.

David Walters

David was born on March 3, 1980, at 9:06 p.m. He weighed 10 lbs. 1oz and was 22 ½” long. My first born and only son. My dream came true: I was a mom! As I held and cuddled my sweet baby, for the first time alone, I whispered how much I loved him and all the plans I had for him; stroller walks to the park, birthday parties, trips to the zoo, and the vow to always protect him from any harm. He was my little angel, my blessing from God. I was a stay-at-home mom. I was going to be there to see all his firsts!

David was a good-natured person. He was kind and gentle with others with a good sense of humor. He was a devout man of God, protective of his family, adored his niece, a true friend, loved animals, and had a bonding way with autistic children. David took strong interest in several sports at a young age beginning with baseball, then paintball, mountain biking, weightlifting, and football.

David began midget football at age 11. When he was a young teen, his grandfather instilled in him the importance of finding something he liked to do, be it a sport or occupation, and giving it his all. David loved football and he learned that weightlifting would make him better at it, so lifting weights became a passion. David’s excellence in the weight room at Cherokee High School in Marlton, New Jersey earned him offensive playing time on the football team all four years.

His hard work in high school paid off. He was offered 11 Division I football scholarships, including one Big Ten offer. David committed to the University of Iowa the summer before his senior year of high school.

When a new coaching staff began in Iowa, David decided to transfer to Wake Forest University in North Carolina. He began his career as a Demon Deacon in 2000. He continued to excel in the weight room and became an impact player, receiving and delivering big hits every game. He stood out for his last two seasons playing offensive tackle.

During the 2002 season, David received a severe concussion during a game but somehow continued playing to the game’s end. He was cleared medically to play the next game, the remainder of the season, and the Seattle Bowl game. I think this final season was the beginning of the end.

After graduating from Wake Forest with a degree in sociology, David went on to play professionally for the Canadian Football League’s Montreal Alouettes. When the CFL decided to let go of almost all their American offensive players, David moved to central Florida where he pursued a career in weight training and nutrition. David did everything he could to stay on his feet, but he struggled to manage the pain he accumulated from years of football.

Eventually, David re-settled in New Jersey. He married and began a new profession as a bricklayer and stone mason. His pain continued, though, and he was caught in a slow but nightmarish spiral of pain and addiction to pain pills.

In 2008, when David was 28, he was diagnosed with Post-Concussion Syndrome. His neurologist described the years of damage as “a lightning storm” in his brain. Talking through David’s concussion history, they estimated 11 concussions or more over his career. He was at high risk for developing serious cognitive issues later in life, and he was facing incredible pain.

Within three years, David’s marriage crumbled. He moved back home with me in 2012 as his pain grew worse. David developed rheumatoid, osteo, and psoriatic arthritis at a young age because of the abuse his body took, and treatments offered little relief. David underwent three unsuccessful surgeries to fix his knees. Then an unsuccessful elbow surgery, leaving him with no cartilage and the elbow of an 80-year-old man. He was told he needed shoulder surgery but couldn’t get around to it because of the constant pain in his head and body.

Through all of this, David’s memory declined to a frightening stage. His difficulties went from “What did I eat for my last meal?” to “I don’t remember Dad giving me this living room set for when I am able to move out on my own again.” His moods grew worse, and he felt extreme irritation over trivial matters. And there were seizures. More and more small seizures, four Grand Mal Seizures, and increasing aggression and violent behaviors.

The kind, gentle, patient David that I knew, my true son, was almost gone. The sweet, appreciative, compassionate David, barely a part of who he’d become. His words in the beginning, when he was thinking about where he felt his life was going, still cause me to cry.

“If I ever have a son, I will never let him play football.”

“Mom, you know one of these seizures, I might not pull through. I don’t want to live like this anymore. I thought of killing myself twice now, but only stop because I don’t want you to come home and find me that way. I don’t want to hurt you Mom.”

David’s list of symptoms grew. Difficulty thinking, planning, and carrying out tasks. Short term memory loss, confusion, mood swings, and impulsive/erratic behavior. Loss of motor skills, tremors, and loss of balance. Aggression, irritability, suicidal thoughts, depression, and apathy.

“You’ve done everything to help me. You take me to all my doctor appointments. You are always encouraging me. You are the best Mom God could have ever given me. We’re a team. I love you, Mom. Thank you, Mom. You love me for me. You help me see things in a different light. I can’t stand the pain in my head. You could never understand the pain in my head. It won’t stop. I pray for God to take me.”

In July 2016, David’s internal rage had become almost completely external. I had to do the most difficult thing in my life. I could no longer care for my slowly dissolving son. I could no longer allow him to continue living in my home. He had to go out on his own, as pathetic as that now feels to say.

He struggled but survived on his own for two more years. I had a pipeline to God’s ears more than ever. Please Lord, make David’s pain stop; please Lord, help him, please, please, please.

David’s downward spiral started because his pain from concussions and other injuries was too much to bear. The college medical staff administered opioids, which we know can lead to addiction. Then, controlled opioids by doctors outside of collegiate walls; addiction. Rehab. Clean. More pain. More opioids. Addiction. Clean. Surgeries. Confusion. Rage. Pain. Out of control pain. Accidental opioid overdose …

On Monday, July 23, 2018 at 9:15 p.m., four days before my 61st birthday, I received every parent’s nightmare phone call. My son, my boy, my beautiful boy, my baby, was gone. God answered my prayers and David’s prayers; David’s pain was no more. No more pain in his head, no more pain in his broken body due to football. He is with his beloved grandparents and great-uncle. He is living in glory with our Lord. This is not how I wanted this prayer to be answered, in this way, but it is what God had planned for my David.

I am still, a year later, trying to accept my loss. I can only hope to help others who are dealing with PCS and suspected CTE in their loved one, to let them know they are not alone. I am here to help in anyway I can through listening and sympathizing with my whole heart. To honor David in the way he would have wanted; to help others on his behalf. The last outward sign of my love for him. David wanted to donate his brain to science, but we were unable to follow through on this wish. I feel David would be happy to know I am trying to spread the word and help others like him. When David passed, in lieu of flowers, a request for donations in his name to the Concussion Legacy Foundation was set up. He would be proud that so many good people who loved him have donated.

David found his soul mate the year before he passed. He was to start his dream job the day after he passed, in a hospital where plans for a flourishing new career were to begin. A few days after David passed, he came to me in the most vivid dream. I try to remember it in my times of uncontrollable grief; he is standing in front of me, smiling, arms wide open saying, “I’m ok Mom.” I know he is, but I am not. I am grateful for all the Concussion Legacy Foundation has, is, and will be doing for our afflicted loved ones, and for us, their parents, family and friends.

Are you or someone you know struggling with lingering concussion symptoms or what you believe may be CTE? We support patients and families through the CLF HelpLine, which provides personalized help to those struggling with the outcomes of brain injury. If you are seeking guidance on how to choose the right doctor, find educational resources, or have any other specific questions, we want to hear from you. Submit your request to the CLF HelpLine and a dedicated member of the Concussion Legacy Foundation team will be happy to assist you.

Joe Walton

Andre Waters

Since the former National Football League player Andre Waters killed himself in November, an explanation for his suicide has remained a mystery. But after examining remains of Mr. Waters’s brain, a neuropathologist in Pittsburgh is claiming that Mr. Waters had sustained brain damage from playing football and he says that led to his depression and ultimate death.

The neuropathologist, Dr. Bennet Omalu of the University of Pittsburgh, a leading expert in forensic pathology, determined that Mr. Waters’s brain tissue had degenerated into that of an 85-year-old man with similar characteristics as those of early-stage Alzheimer’s victims. Dr. Omalu said he believed that the damage was either caused or drastically expedited by successive concussions Mr. Waters, 44, had sustained playing football.

In a telephone interview, Dr. Omalu said that brain trauma “is the significant contributory factor” to Mr. Waters’s brain damage, “no matter how you look at it, distort it, bend it. It’s the significant forensic factor given the global scenario.”

He added that although he planned further investigation, the depression that family members recalled Mr. Waters exhibiting in his final years was almost certainly exacerbated, if not caused, by the state of his brain — and that if he had lived, within 10 or 15 years “Andre Waters would have been fully incapacitated.”

Dr. Omalu’s claims of Mr. Waters’s brain deterioration — which have not been corroborated or reviewed — add to the mounting scientific debate over whether victims of multiple concussions, and specifically longtime N.F.L. players who may or may not know their full history of brain trauma, are at heightened risk of depression, dementia and suicide as early as midlife.

The N.F.L. declined to comment on Mr. Waters’s case specifically. A member of the league’s mild traumatic brain injury committee, Dr. Andrew Tucker, said that the N.F.L. was beginning a study of retired players later this year to examine the more general issue of football concussions and subsequent depression.

“The picture is not really complete until we have the opportunity to look at the same group of people over time,” said Dr. Tucker, also team physician of the Baltimore Ravens.

The Waters discovery began solely on the hunch of Chris Nowinski, a former Harvard football player and professional wrestler whose repeated concussions ended his career, left him with severe migraines and depression, and compelled him to expose the effects of contact-sport brain trauma. After hearing of the suicide, Mr. Nowinski phoned Mr. Waters’s sister Sandra Pinkney with a ghoulish request: to borrow the remains of her brother’s brain.

The condition that Mr. Nowinski suspected might be found in Mr. Waters’s brain cannot be revealed by a scan of a living person; brain tissue must be examined under a microscope. “You don’t usually get brains to examine of 44-year-old ex-football players who likely had depression and who have committed suicide,” Mr. Nowinski said. “It’s extremely rare.”

Editors’ Picks

How to Ensure a Peaceful Trip With Your Extended Family

Will Free Beer Make Travelers More Responsible?

Can I Confront the Woman Who Stole My Late Sister’s Evening Gowns?

As Ms. Pinkney listened to Mr. Nowinski explain his rationale, she realized that the request was less creepy than credible. Her family wondered why Mr. Waters, a hard-hitting N.F.L. safety from 1984 to 1995 known as a generally gregarious and giving man, spiraled down to the point of killing himself.

Ms. Pinkney signed the release forms in mid-December, allowing Mr. Nowinski to have four pieces of Mr. Waters’s brain shipped overnight in formaldehyde from the Hillsborough County, Fla., medical examiner’s office to Dr. Omalu in Pittsburgh for examination.

He chose Dr. Omalu both for his expertise in the field of neuropathology and for his rare experience in the football industry. Because he was coincidentally situated in Pittsburgh, he had examined the brains of two former Pittsburgh Steelers players who were discovered to have had postconcussive brain dysfunction: Mike Webster, who became homeless and cognitively impaired before dying of heart failure in 2002; and Terry Long, who committed suicide in 2005.

Mr. Nowinski, a former World Wrestling Entertainment star working in Boston as a pharmaceutical consultant, and the Waters family have spent the last six weeks becoming unlikely friends and allies. Each wants to sound an alarm to athletes and their families that repeated concussions can, some 20 years after the fact, have devastating consequences if left unrecognized and untreated — a stance already taken in some scientific journals.

“The young kids need to understand; the parents need to be taught,” said Kwana Pittman, 31, Mr. Waters’s niece and an administrator at the water company near her home in Pahokee, Fla. “I just want there to be more teaching and for them to take the proper steps as far as treating them.

“Don’t send them back out on these fields. They boost it up in their heads that, you know, ‘You tough, you tough.’ ”

Mr. Nowinski was one of those tough kids. As an all-Ivy League defensive tackle at Harvard in the late 1990s, he sustained two concussions, though like many athletes he did not report them to his coaches because he neither understood their severity nor wanted to appear weak. As a professional wrestler he sustained four more, forcing him to retire in 2004. After he developed severe migraines and depression, he wanted to learn more about concussions and their effects.

That research resulted in a book published last year, “Head Games: Football’s Concussion Crisis,” in which he detailed both public misunderstanding of concussions as well as what he called “the N.F.L.’s tobacco-industry-like refusal to acknowledge the depths of the problem.”

Football’s machismo has long euphemized concussions as bell-ringers or dings, but what also alarmed Mr. Nowinski, 28, was that studies conducted by the N.F.L. on the effects of concussions in players “went against just about every study on sports concussions published in the last 20 years.”

Studies of more than 2,500 former N.F.L. players by the Center for the Study of Retired Athletes, based at the University of North Carolina, found that cognitive impairment, Alzheimer’s-like symptoms and depression rose proportionately with the number of concussions they had sustained. That information, combined with the revelations that Mr. Webster and Mr. Long suffered from mental impairment before their deaths, compelled Mr. Nowinski to promote awareness of brain trauma’s latent effects.

Then, while at work on Nov. 20, he read on Sports Illustrated’s Web site, si.com, that Mr. Waters had shot himself in the head in his home in Tampa, Fla., early that morning. He read appraisals that Mr. Waters, who retired in 1995 and had spent many years as an assistant coach at several small colleges — including Fort Valley (Ga.) State last fall — had been an outwardly happy person despite his disappointment at not landing a coaching job in the N.F.L.

Remembering Mr. Waters’s reputation as one of football’s hardest-hitting defensive players while with the Philadelphia Eagles, and knowing what he did about the psychological effects of concussions, Mr. Nowinski searched the Internet for any such history Mr. Waters might have had.

It was striking, Mr. Nowinski said. Asked in 1994 by The Philadelphia Inquirer to count his career concussions, Mr. Waters replied, “I think I lost count at 15.” He later added: “I just wouldn’t say anything. I’d sniff some smelling salts, then go back in there.”

Mr. Nowinski also found a note in the Inquirer in 1991 about how Mr. Waters had been hospitalized after sustaining a concussion in a game against Tampa Bay and experiencing a seizure-like episode on the team plane that was later diagnosed as body cramps; Mr. Waters played the next week.

Because of Dr. Omalu’s experience on the Webster and Long cases, Mr. Nowinski wanted him to examine the remaining pieces of Mr. Waters’s brain — each about the size of a small plum — for signs of chronic traumatic encephalopathy, the tangled threads of abnormal proteins that have been found to cause cognitive and intellectual dysfunction, including major depression. Mr. Nowinski tracked down the local medical examiner responsible for Mr. Waters’s body, Dr. Leszek Chrostowski, who via e-mail initially doubted that concussions and suicide could be related.

Mr. Nowinski forwarded the Center for the Study of Retired Athletes’ studies and other materials, and after several weeks of back-and-forth was told that the few remains of Mr. Waters’s brain — which because Waters had committed suicide had been preserved for procedural forensic purposes before the burial — would be released only with his family’s permission.

Mr. Nowinski said his call to Mr. Waters’s mother, Willie Ola Perry, was “the most difficult cold-call I’ve ever been a part of.”

When Mr. Waters’s sister Tracy Lane returned Mr. Nowinski’s message, he told her, “I think there’s an outside chance that there might be more to the story.”

“I explained who I was, what I’ve been doing, and told her about Terry Long — and said there’s a long shot that this is a similar case,” Mr. Nowinski said.

Ms. Lane and another sister, Sandra Pinkney, researched Mr. Nowinski’s background, his expertise and experience with concussions, and decided to trust his desire to help other players.

“I said, ‘You know what, the only reason I’m doing this is because you were a victim,’ ” said Ms. Pittman, Mr. Waters’s niece. “I feel like when people have been through things that similar or same as another person, they can relate and their heart is in it more. Because they can feel what this other person is going through.”

Three weeks later, on Jan. 4, Dr. Omalu’s tests revealed that Mr. Waters’s brain resembled that of an octogenarian Alzheimer’s patient. Nowinski said he felt a dual rush — of sadness and success.

“Certainly a very large part of me was saddened,” he said. “I can only imagine with that much physical damage in your brain, what that must have felt like for him.” Then again, Mr. Nowinski does have an inkling.

“I have maybe a small window of understanding that other people don’t, just because I have certain bad days that when I know my brain doesn’t work as well as it does on other days — and I can tell,” he said. “But I know and I understand, and that helps me deal with it because I know it’ll probably be fine tomorrow. I don’t know what I would do if I didn’t know.”

When informed of the Waters findings, Dr. Julian Bailes, medical director for the Center for the Study of Retired Athletes and the chairman of the department of neurosurgery at West Virginia University, said, “Unfortunately, I’m not shocked.”

In a survey of more than 2,500 former players, the Center for the Study of Retired Athletes found that those who had sustained three or more concussions were three times more likely to experience “significant memory problems” and five times more likely to develop earlier onset of Alzheimer’s disease. A new study, to be published later this year, finds a similar relationship between sustaining three or more concussions and clinical depression.

Dr. Bailes and other experts have claimed the N.F.L. has minimized the risks of brain trauma at all levels of football by allowing players who sustain a concussion in games — like Jets wide receiver Laveranues Coles last month — to return to play the same day if they appear to have recovered. The N.F.L.’s mild traumatic brain injury committee has published several papers in the journal Neurosurgery defending that practice and unveiling its research that players from 1996 through 2001 who sustained three or more concussions “did not demonstrate evidence of neurocognitive decline.”

A primary criticism of these papers has been that the N.F.L. studied only active players, not retirees who had reached middle age. Dr. Mark Lovell, another member of the league’s committee, responded that a study using long-term testing and monitoring of the same players from relative youth to adulthood was necessary to properly assess the issue.

“We want to apply scientific rigor to this issue to make sure that we’re really getting at the underlying cause of what’s happening,” Dr. Lovell said. “You cannot tell that from a survey.”

Dr. Kevin Guskiewicz is the director of the Center for the Study of Retired Athletes and a member of U.N.C.’s department of exercise and sport science. He defended his organization’s research: “I think that some of the folks within the N.F.L. have chosen to ignore some of these earlier findings, and I question how many more, be it a large study like ours, or single-case studies like Terry Long, Mike Webster, whomever it may be, it will take for them to wake up.”

The N.F.L. players’ association, which helps finance the Center for the Study of Retired Athletes, did not return a phone call seeking comment on the Waters findings. But Merril Hoge, a former Pittsburgh Steelers running back and current ESPN analyst whose career was ended by severe concussions, said that all players — from retirees to active players to those in youth leagues — need better education about the risks of brain trauma.

“We understand, as players, the ramifications and dangers of paralysis for one reason — we see a person in a wheelchair and can identify with that visually,” said Mr. Hoge, 41, who played on the Steelers with Mr. Webster and Mr. Long. “When somebody has had brain trauma to a level that they do not function normally, we don’t see that. We don’t witness a person walking around lost or drooling or confused, because they can’t be out in society.”

Clearly, not all players with long concussion histories have met gruesome ends — the star quarterbacks Steve Young and Troy Aikman, for example, were forced to retire early after successive brain trauma and have not publicly acknowledged any problems. But the experiences of Mr. Hoge, Al Toon (the former Jets receiver who considered suicide after repeated concussions) and the unnamed retired players interviewed by the Center for the Study of Retired Athletes suggest that others have not sidestepped a collision with football’s less glorified legacy.

“We always had the question of why — why did my uncle do this?” said Ms. Pittman, Mr. Waters’s niece. “Chris told me to trust him with all these tests on the brain, that we could find out more and help other people. And he kept his word.”