“You typically get the testimony after someone has made their way to the other side of healing. Well, I’m right in the midst of it all, and now serve as my own shelter from the storm.”

1. What did you know about concussions while playing youth sports?

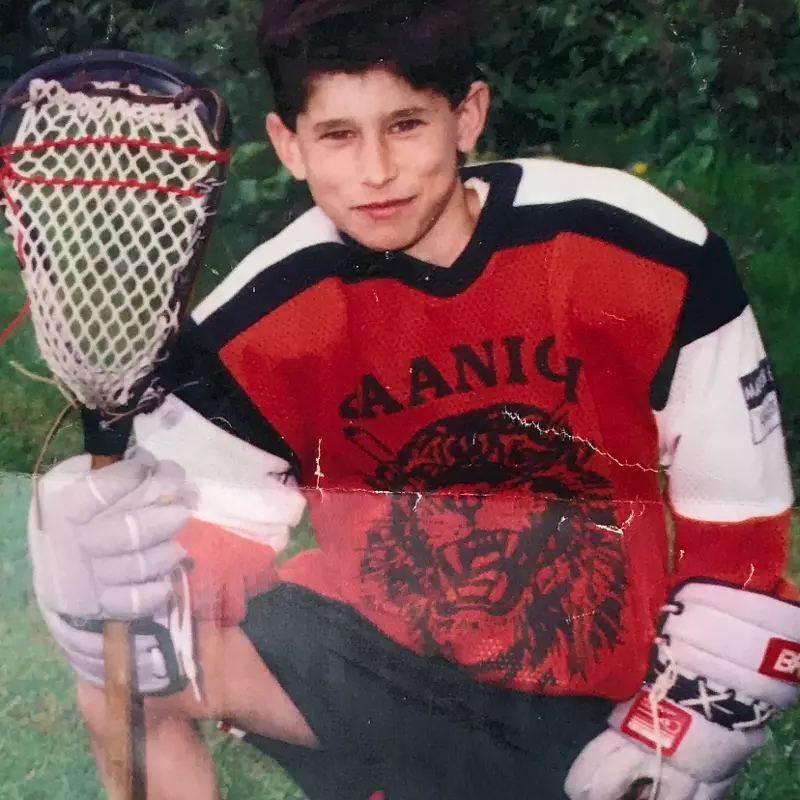

I didn’t know what a concussion was until I suffered one in 10th grade. My coaches at the time weren’t educated on the impact of head injuries; I learned through trial and error. A goal line stop that put our team in position to win became a stale joke from my head coach: “Don’t knock yourself out again!” Having complete disregard for my body as a defender was praised. My senior year superlative was, “Most likely to give someone whiplash.” I figured it was a part of the game and came with the territory. “You’re either the hammer or the nail…”

I also remember my brother taking a hit on the sideline during a preseason youth game. I jumped the ramp and ran onto the field because I immediately knew what happened. A concussion ended his playing career. He was probably a bigger football fan than me so to see him call it quits weighed on my spirit for a while. He didn’t have the same enthusiasm for the game after that.

2. You suffered two concussions this past season that led to Post-Concussion Syndrome (PCS). What was that experience like?

Concussions are unfortunately a part of the game, but they aren’t always reported as such. There is more research being done to remove the head from the tackle and protect the defenseless player. You see guys now wearing neck collars, and some teams requiring Guardian Caps over helmets during practice. It’s a pretty nuanced topic in my opinion. Players playing through concussions is also a prevalent part of football culture. We all saw the situation with Tua Tagovailoa and what was blatantly apparent as negligence. There is neglect within the current concussion protocol across the board. As a professional athlete we are conditioned to focus on the main thing no matter what, which is our job security. There’s a quote I’ve heard my entire career from coaches: “The best ability is availability.” This is the same mentality carried by athletes who play through injuries. You can’t secure a job if you’re not available to perform.

The number one priority should be player safety. Every level of football should be intentional about enacting player safety measures. I can relate from personal experience. I suffered two concussions in back-to-back games, where the second could’ve been avoided had I healed fully before returning to play. I was told I cleared protocol without a concussion, so I was unsure why I didn’t feel normal. I voiced my emotional distress as my anxiety intensified. I soon learned that this injury isn’t understood by many in the profession. There is still a lack of education from all involved including players. You can’t suppress and fight your way through a brain injury. You will be forced to surrender as your body heals. I now tell myself every day, “Quality of life is more important than job security.”

3. How did things progress from the first concussion to the second? Did you experience any symptoms?

After the first hit my body went limp from the neck down. I was able to get up after a few seconds and stumbled a bit looking to see if anyone saw from the sideline. That’s when the referee pulled me from the game to be checked for a concussion. I was told I cleared protocol and was allowed to return to the field. I suddenly was no longer able to manage emotions as my anxiety spiraled downward from there. The game ended and my frustration was at an all-time high. A week later I lost consciousness on impact during a second hit and couldn’t remember anything as I walked out of the medical tent. Chronic headaches, light sensitivity, and brain fog were symptoms that lasted long enough for my team to place me on IR for the remainder of the season. I had to completely detach from my normal life and start from scratch in my recovery.

4. How has your PCS affected relationships with teammates, friends, family, and people close to you?

There is a sense of loneliness dealing with PCS because it removes you from your normal headspace. It’s an invisible weight I carried on my shoulders daily. My dreams were sinister, so nightfall brought immense anxiety. I became emotionally dysregulated and drifted in survivor mode. Thankfully my faith has kept me upright. As self-sufficient as I am, I’m not afraid to ask for help when I’ve done all I can on my own. The relationships with my family and teammates have kept me levelheaded during this time. It’s very easy to slip into depression when you thrive in solitude. I made the necessary adjustments and stuck around people who cared about me. There is truth in the saying, “The lone wolf dies.” You can’t get through this alone without a solid community around you.

5. People often say athletes know what they sign up for in regard to concussion awareness. Do you think athletes are aware of the impact concussions can have, especially if not treated properly?

Athletes don’t always think about it, but we take the risk every time we step on the field. We all expect to be treated properly and it doesn’t always happen post-concussion. Everything is reactive instead of proactive. Player safety isn’t seriously considered until someone’s pockets are hurt, life threatening injuries occur, or a player dies. I always say it’s the responsibility of those involved to make yourself aware of the risks you take playing this game. Nobody ever thinks it can happen to them until it does.

6. Have any treatments helped improve your symptoms?

Cognitive behavioral therapy for sure. I also worked with a vestibular specialist for balance and neuromuscular retraining. After the season I transitioned over into visceral manipulation and cranial sacral therapy. I’m now working with a clinical neuropsychologist at the Concussion Institute. My physical therapists put a plan together for me to make a full recovery by next season. I look forward to being further ahead than I was before my injury.

Dr. Schwartz from the Institute also mentioned Dr. Chris Nowinski’s advocacy for concussion safety. I did my research on it and made a pledge to the foundation.

7. Was there anything in particular that drove you to that commitment to research?

As pro athletes, we are conditioned to think this game will reward us for playing through pain. Once I realized it didn’t owe me anything, I started taking more accountability for my health. I’ve used football as an outlet and vehicle my entire career, but I won’t turn a blind eye to the neglect I’ve experienced. CLF is making room for those who support strengthening player safety. The only way we’ll see change is through research and policy shifting. Having uncomfortable conversations around concussions in sports is necessary. It’s time we all look in the mirror.

8. Why do you want to tell your story?

You typically get testimony after someone has made their way to the other side of healing. Well, I’m right in the midst of it all, and now serve as my own shelter from the storm. Somewhere along the way I learned to appreciate uncertainty and exit the loop of fear. I speak not only in regard to what I endured, but also for anyone else who is silently suffering from PCS.

9. What is your hope for the future of football?

Football is growing globally and as more players leave the game, others join. I hope we continue supporting what research shows and educate on the impact of repeat head injuries. The game is more than X’s and O’s; there’s no real-life counsel in your playbook. You can’t take it with you when you leave the game. I hope the culture of dismissing injuries shifts so more athletes don’t lose their mind, or their lives when the game ends for them.

10. How do you hope to use your role as a Concussion Legacy Captain to impact your sport?

My voice is one of the most powerful tools God gave me. I have many tangible experiences to reference. Instead of clinging to false hope, I decided to actively join the change I wish to see.

11. Finally, what would your message of hope and inspiration be to others who might be recovering from a concussion right now?

Be firm and advocate for yourself! Listen to your body. We are much stronger when we’re honest and vulnerable about what we feel. The clichés are true. Be hopeful in the presence of discomfort. Go back to a point in time where life was simple. Rediscover your joy and sit in these moments a little longer. Edit your life and the people around you. Lean on your family, close friends, and most importantly your faith. Get outside in nature and adventure again. Dedicate this challenging season of life for deeper self-mastery. When you wake up and put two feet on the ground, be determined your pain will subside. I channeled the same approach I had for football into healing. Only in my suffering did I find true peace. It may feel like you’re going from one extreme to the next, but your story too will end in triumph.