Warning: This story contains mentions of suicide that may be triggering to some readers.

A Life Gone Too Soon

Wyatt Byron Bramwell had it all: he was a handsome, kind, funny, and smart 18-year-old with so much to offer. He was a beloved son, brother, grandchild, great-grandchild, cousin, and friend. Wyatt was born on a warm, beautiful summer day in Blue Springs, Missouri, on August 19, 2000; he took his life on a very similar beautiful summer day in Pleasant Hill, Missouri, on July 30, 2019.

Before his passing, Wyatt graduated summa cum laude from Pleasant Hill High School with a 3.8 GPA and membership in the National Honor Society. A gifted student, he was preparing to attend the University of Missouri College of Engineering. Everyone in our family was immensely proud of all Wyatt’s achievements during his brief 18 years on Earth; the future looked extremely bright. He was not a perfect human being, but pretty ideal for a teenager.

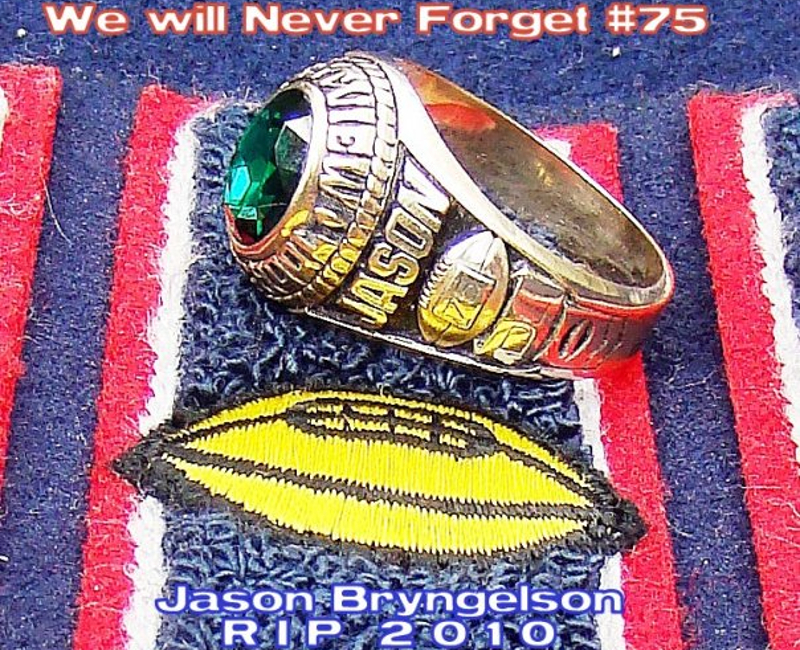

Athletics came naturally to Wyatt, who excelled at every sport he touched. He started playing tackle football with pads and helmets at age eight, focusing on it all the way to high school. His routine was intense but regimented, waking up weekday mornings by himself at 4:30 a.m., working out at the local gym before it was time for class. Wyatt also made sure to complete his course work, maintain a high GPA, and earn academic letters for his studies.

Wyatt missed his sophomore year of playing football due to an injury but supported the team any way he could, including attending practices and games, and recording them on video to watch later. He then made the varsity squad as a junior and senior. A starter and standout on both sides of the ball, he alternated between wide receiver, cornerback, and placeholder. It’s not an understatement to say Wyatt was one of the best on the field and on the team overall. He was a dynamo, a star in the making. Friday nights became “can’t miss” events, centered around Wyatt’s football schedule.

A Sudden Change

Wyatt’s last ever football game was in November of 2018, suddenly deciding to quit the sport after his senior season was over. This came as a surprise to everyone, as his dream was always to eventually play for a Division I university. He never offered a reason why, stating he simply wanted to focus on school. In hindsight, Wyatt had already begun to experience symptoms and suspected he might have CTE, which no one would know until later.

In May of 2019, Wyatt left on a scuba diving trip to Bonaire with his girlfriend and her parents, to celebrate graduating from high school. Upon their return, he demanded a family meeting and admitted he had:

- Received a speeding ticket prior to leaving on vacation

- Smoked marijuana a couple of times

- Been fired for absenteeism from his job at Walmart (and not laid off like he’d originally said)

- Tried to overdose one night (despite repeated urging to provide further details, Wyatt wouldn’t reveal when this occurred or what medication he’d taken)

Then Wyatt informed his parents he no longer wanted their help and was moving out. He relinquished his car, phone, and the expensive 18th birthday watch his parents had given him. For about two months, Wyatt was estranged from his mother and father, despite multiple attempts to communicate and reconcile. He lived for a while with a friend in Pleasant Hill before moving to a family member’s home nearby.

On the afternoon of July 30, 2019, an otherwise beautiful sunny Tuesday, Wyatt borrowed a car to retrieve belongings from a friend’s house. He’d said it was a simple errand and would return shortly. Instead, Wyatt traveled to a secluded area in his hometown and filmed a message on his phone, before taking his life.

In the video, Wyatt admitted to being depressed for a long time, probably since his freshman year. He also confessed to having racing thoughts and hearing voices he referred to as demons. He said, “My head is pretty messed up and damaged,” and that he’d covered it up with sports, video games, and hanging out with friends, but it only got worse over the years.

“I took a lot of hits through football,” said Wyatt. “I took a lot of concussions, and a lot of times I never told anybody about how I was feeling in my head after a hit, I just kind of kept playing which was not smart on my end. I know that.”

Wyatt also specifically requested his brain be donated for study, saying, “I feel like it’ll be closure for me and it’ll be closure for you guys to know that maybe I suffered from brain damage, maybe that was the reason.”

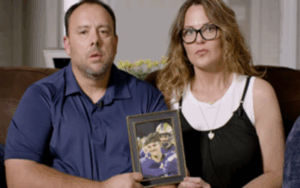

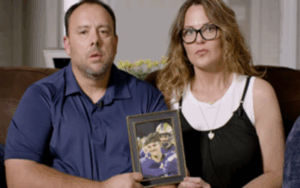

Bringing Meaning to Loss

Despite their overwhelming confusion and profound grief in the moment, Wyatt’s parents, Bill and Christie, were able to contact the UNITE Brain Bank and donate Wyatt’s brain for study, fulfilling his final request. We all nervously awaited the results, not really believing he suffered from CTE. After all, he’d been an excellent and committed student. He was beyond trustworthy, responsible, predictable and easygoing; that is, until his last 57 days, but couldn’t his behavior be attributed to the adolescence of a growing boy?

While Wyatt had played football since age six, he’d never even complained of headaches nor mentioned any concerns about his brain or CTE. He hadn’t displayed the behaviors of hearing demons or voices as he described before his death. All those who loved Wyatt remained confused and in a perpetual state of shock, having to come to terms with a new normal.

In September 2020, Lisa McHale of the BU CTE Center and the Concussion Legacy Foundation arranged a conference call between our family and Dr. Ann McKee to review the study findings. Dr. McKee revealed Wyatt suffered from stage 2 (of 4) CTE, the first teenager and, to date, youngest athlete to have such advanced pathology of the disease.

Bill and Christie shared Wyatt’s diagnosis in November 2023, as part of a New York Times special feature on young athletes who lost their lives and were later diagnosed with CTE.

“We were completely shocked to learn that Wyatt had CTE,” said Wyatt’s parents. “While this is very painful for us to share, we have several reasons for revealing all this publicly. One, so families can have open conversations about allowing their children to play contact sports while offering others’ patterns they may recognize. Two, we want Wyatt’s legacy to be more than his sudden suicide and to serve as a cautionary tale to all football parents, as he had no visible symptoms until it was too late. Finally, and ultimately, we hope by sharing Wyatt’s story, it can bring some meaning to our loss.”

______________________________

Suicide is preventable and help is available. If you are concerned that someone in your life may be suicidal, the five #BeThe1To steps are simple actions anyone can take to help someone in crisis. If you are struggling to cope and would like some emotional support, call the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988 to connect with a trained counselor. It’s free, confidential, and available to everyone in the United States. You do not have to be suicidal to call.

Are you or someone you know struggling with lingering concussion symptoms? We support patients and families through the CLF HelpLine, providing personalized help to those struggling with the outcomes of brain injury. Submit your request today and a dedicated member of the Concussion Legacy Foundation team will be happy to assist you.