Kelly Catlin

Kelly was born a triplet on November 3, 1995 in Arden Hills, Minnesota. She, her sister Christine, and her brother Colin were a superpowered trio from the very beginning.

All three children were tremendous athletes and students, but Kelly’s intensity and competitiveness always stood out. Colin introduced her to cycling when she was a teenager and she never looked back. Cycling was a vehicle for her competitiveness and perfectionism and she loved it. She could always do more and do better on the bike.

Kelly started dominating competitions against her peers in high school, and before long she was beating members of the University of Minnesota men’s cycling team while she was still in high school. The cycling community took notice. In 2014, she attended a camp organized by the US Olympic Committee and was chosen to train for the 2016 Olympics in Rio de Janeiro.

She trained with USA Cycling in places like Colombia and Manchester while she balanced dual degrees in Biomedical Engineering and Chinese at the University of Minnesota. In Rio, she and the U.S. team won silver while we watched her race on a track for the very first time. In addition to the Olympic medal, Kelly won a remarkable five USA U23 National Championships. At home, Kelly became a local legend, speaking at assemblies and cycling clubs in Minnesota, and encouraging young riders.

After finishing her undergraduate degree, Kelly tried to balance three enormous commitments. She still competed internationally, started racing for Rally UHC Cycling in Minnesota, and enrolled at Stanford in Fall 2018. Her list of commitments was piling up.

“The truth is that most of the time, I don’t make everything work. It’s like juggling with knives, but I really am dropping a lot of them. It’s just that most of them hit the floor and not me,” she wrote in a VeloNews journal.

But on she went, unable to say no and motivated to do all she could.

“Kelly wanted to achieve perfection in everything she did, never wanted to show weakness, always wanted to make everyone proud, and first and foremost, never wanted to let anyone down,” said her coach Andy Sparks.

On January 5, 2019, Kelly suffered a concussion in a training event in California. The crash left cracks in the front and back of her helmet. The next day, she left the California event to train with the U.S. national team in Colorado. Kelly complained to us of severe headaches, dizziness, nausea, and sensitivity to light. Depression and an altogether different Kelly soon followed.

Our perpetually determined daughter began embracing nihilism. Training usually invigorated her, but workouts now left her feeling apathetic. In our phone calls, Kelly spoke like an entirely different, more detached person. Like a robot.

With Kelly now back at Stanford, she emailed us a suicide note. She said her thoughts were constantly racing and her mind was spinning. We immediately called the school, and campus police halted her suicide attempt. After 72 hours in a psychiatric unit and a week in a hospital, we stayed with Kelly in California for a week.

She seemed chipper. She just needed some time alone to rest. Everything was fine, she said. We flew back to Minnesota.

In our now daily calls, Kelly updated us on her return to school and her group therapy sessions, which she deemed worthless and a waste of time. She resumed training at an absurd level, completing three high-intensity workouts per day and going 11 days without rest at one point. But new health issues arose.

Kelly’s first suicide attempt caused hypoxic damage and elevated her cardiac enzymes, resulting in shortness of breath. Her concussion symptoms also returned. She had to close her eyes in an Uber ride to beat a headache and reduce nausea. Now unable to train, she was ruled out of participating in the UCI track world championships in Poland in late February. Kelly was devastated and told us she contemplated ending her cycling career.

We called and texted Kelly during the first week of March to try and encourage her to embrace some much-needed rest. After Wednesday we received no response. On Friday morning, March 9, my wife Carolyn called Stanford police. They found Kelly had died by suicide in her apartment the night before.

The news gutted our family and the cycling community at large. How could someone with such limitless potential choose to end her life? As we grieve, we must also learn from Kelly’s life to prevent more of these horror stories from happening in the future.

We believe a combination of her personality, overtraining, and her concussion caused her mental health to deteriorate. Kelly’s relentless determination, which allowed her to fly to such great heights, led her to deny she was in trouble or accept help at the first signs of struggle. When she needed to slow down, she did the opposite, training harder than ever on top of a challenging workload. Her persistence had paid off previously, but it wasn’t helpful when she was all the while suffering from a concussion.

Her muscles may have gotten brief rest, but her brain never did. We want to share the story of Kelly’s death because it would have been so easily preventable and other people can be saved. I believe a single person recognizing Kelly’s Post-Concussion Syndrome could have made all the difference.

If one medical person had shown her this article, or explained that her confusion, apathy, despair, trouble concentrating, trouble sleeping and heart problems were due to Post-Concussion Autonomic Dysregulation, she would have rested like she needed to. This wonderful, gifted person would be alive today. All of her symptoms probably would have improved with two weeks of good rest. Many athletic programs have set protocols for return to activity after concussions. She was seen and evaluated for her head injury at both the Olympic Training Center and at Stanford Medical Center, but to our knowledge they neither put her on a concussion protocol and return to activity protocol, nor advised her coaches to institute and enforce such a protocol.

After her death, we donated Kelly’s brain to the UNITE Brain Bank in Boston to investigate any possible damage caused by her concussion and to seek explanations for her neurologic symptoms in the last few months of life. We hope the results of her brain study and her story can save future athletes from a far too common fate.

Suicide is preventable and help is available. If you are concerned that someone in your life may be suicidal, the five #BeThe1To steps are simple actions anyone can take to help someone in crisis. If you are struggling to cope and would like some emotional support, call the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988 to connect with a trained counselor. It’s free, confidential, and available to everyone in the United States. You do not have to be suicidal to call. If you’re not comfortable talking on the phone, consider using the Lifeline Crisis Chat here.

If you or someone you know is struggling with lingering concussion symptoms, ask for help through the CLF HelpLine. We provide personalized help to those struggling with the outcomes of brain injury. Submit your request today and a dedicated member of the Concussion Legacy Foundation team will be happy to assist you.

Ronnie Caveness

David Cerbin

Tony Cesario

Joseph Chernach

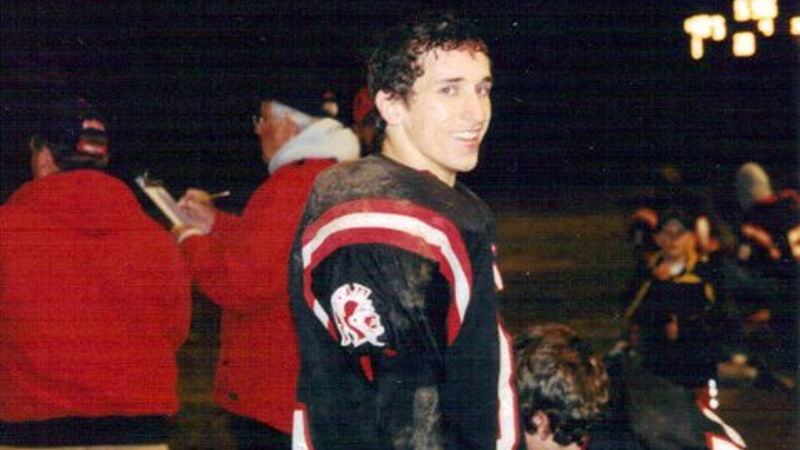

Joseph Chernach traveled to his next journey on June 6, 2012. With his Forest Park Trojan and Green Bay Packer jerseys, his difficulties and struggles with depression finally came to end at the age of 25.

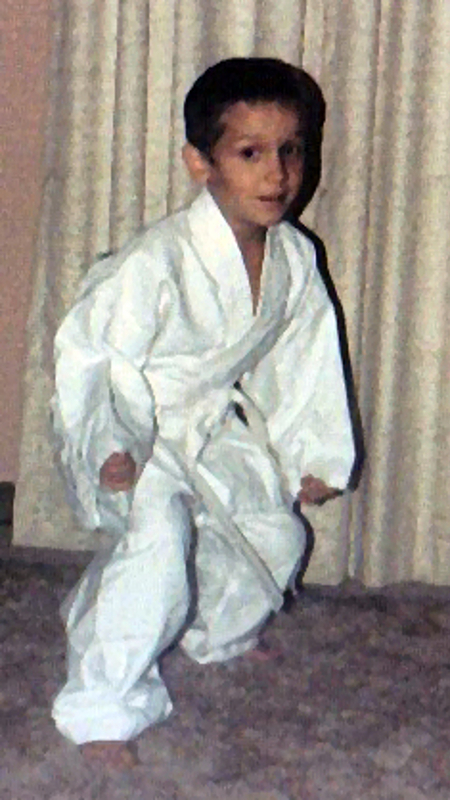

Joseph was a competitive and talented athlete from an early age, playing summer baseball, wrestling since the age of six and throughout high school, a pole vaulter in track, and pop-warner, JV and Varsity football in high school. He won many medals and trophies from grade school through high school.

He was the Michigan High School Upper Peninsula pole vault champion, Michigan High School state wrestling champion, named all U.P class D defensive back, all State class D defensive back, MVP of football along with senior athlete. He was proud to play in the Michigan High school state football finals in 2004 with the Forest Park Trojans.

His greatest accomplishment was graduating with high honors from Forest Park High School in 2005.

He also attended Central Michigan University in Mt. Pleasant, Michigan with plans to graduate with a degree in Physical Therapy.

Joseph was baptized at the Northfield Lutheran Church, Hixton, WI, and confirmed at the United Christ Methodist Church in Crystal Falls, MI. His Facebook page reflects his religious views as “God Loves Me.”

Joseph was fun, active and lived for making people laugh and his sense of humor touched many. He was a fan of the Michigan Wolverines, Milwaukee Brewers and Green Bay Packers. He loved to fish and deer hunt in Wisconsin on the family farm.

Joseph leaves behind many family and friends, father Jeffrey Chernach, mother Debra (Fred) Pyka, brothers Tyler (Michelle) and Seth, sister Nicole, step-sister Samantha, Grandmother Lolly, nieces Braylee and Layla and the Forest Park Class of 2005.

A yearly scholarship has been set-up in his memory.

Joseph Chernach Memorial Scholarship

Forest Park High School

801 Forest Parkway

Crystal Falls, MI 49920

In Joseph’s final few years, he suffered with depression and unable to overcome all the struggles and difficulties with life. CTE was destroying his brain until he could no longer go on with life here. Looking at his headstone in the cemetery is very heartbreaking knowing he is gone. We will never see him graduate college, marry, become a father, and live a happy, healthy and successful life.

We will always wonder what he would have accomplished in his lifetime and we know he will be waiting to see us all again, until that time comes, we are left with the devastation of losing him and living our lives without him. We are all grateful for having him in our lives for almost 26 years. Until we meet again, our love goes with you and our souls wait to join you.

For almost 20 years, the NFL covered up and denied evidence to the connection between brain damage and football. How many people have died from this brain disease whose families are unaware? How much progress could have been made for research, a cure, and the safety and health of everyone had this evidence been made public 20 years ago?

I have contacted the news media, local congressman, senator, representative, the National Federation of High schools and the White House with my son’s story and concerns with sports, head trauma and CTE. The safety and health of our children are at risk. I hope someone will finally listen.

We love you and miss you Joseph and we’ll all be together again one day soon.

We are grateful to the Concussion Legacy Foundation for the research and diagnosis to finally give us the answers to what caused Joseph’s depression and early death. Joseph never played college or pro-sports and we do not know of any concussions during his middle or high school years. This is the report we received from Dr. Ann McKee at the BU CTE Center in December 2013:

“Fixed tissue samples were received from Sacred Heart Pathology Department, Eau Claire, Wisconsin on 9/6/12. There were no obvious abnormalities. However, microscopic analysis of the tissue revealed considerable pathological tau deposits as neurofibrillary tangles throughout the frontal brain regions. There were also very severe changes in the brainstem, with numerous tau neurofibrillary tangles in the locus coeruleus, an area of the brain thought to play a role in mood regulation and depression. The changes in the frontal lobes and locus coeruleus were the most severe I’ve seen in a person this age. These findings indicate Stage II, possibly Stage III (with Stage IV being most severe) CTE and are particularly noteworthy, given the young age of the subject.”

Read more about Joseph and his story from his parents and BuzzFeed News.