Todd Eagen

Ron East

Ray Easterling

Born to Elmer and Vivian Easterling in Richmond, Virginia, on September 3, 1949, Ray was the second of three, athletic boys. He grew up in what was a rural setting in Chesterfield County, roaming the creeks and fields as little boys do. He wrote in his third grade biography that he wanted to be a professional football player after watching his cousin, Carroll Dale, on television playing for the Green Bay Packers.

In the eighth grade, Ray was 4’10” and weighed 98 pounds. He was a wiry, little fellow! He was the one in pickup football the quarterback always told to “go long”. He tried out for his school’s football team, but they wouldn’t give him a uniform. Seeing his son’s intense desire to play football, his dad took him to a private school, obtained a scholarship for him, and the rest, athletically, is history.

Nothing had ever come easy for Ray. He was a fighter and a scrapper. His friend, Jimmy Lewis, would say that he had to rescue Ray from his scrapes!

At Collegiate School, Ray lettered in five sports and was voted the best all-around athlete his senior year. Then came the search for a college to give him a scholarship. His dad took him around Virginia and North Carolina to no avail. Finally, because his brother, Robert, was going there, he walked on at the University of Richmond. By his sophomore year he earned a scholarship to play football for UR.

His junior year play at cornerback was outstanding. By the time spring practice rolled around, pro scouts were in town to watch him. But it wasn’t to be an easy road. An injury to his knee put him in a cast for six weeks. Rehab included running the hills in a local park with his brother, Robert. He came back from the injury to play well his senior year at UR with numerous awards including All Southern Conference and Little All-American. He played in the Coaches All-American game. Coach “Bear” Bryant made a memorable impression on this college senior. In the spring of 1972, Ray was drafted by the Atlanta Falcons in the ninth round.

Arriving in Atlanta was a dream-come- true for Ray. If there wasn’t a party, Ray started one. But by the time he was back in Richmond for the off-season he was crying himself to sleep at night. He wondered, “if you get everything you ever wanted and still feel empty, what is life all about?”. The summer of 1973, Ray knelt in a cow pasture in rural Virginia and trusted Jesus Christ as his Lord and Savior.

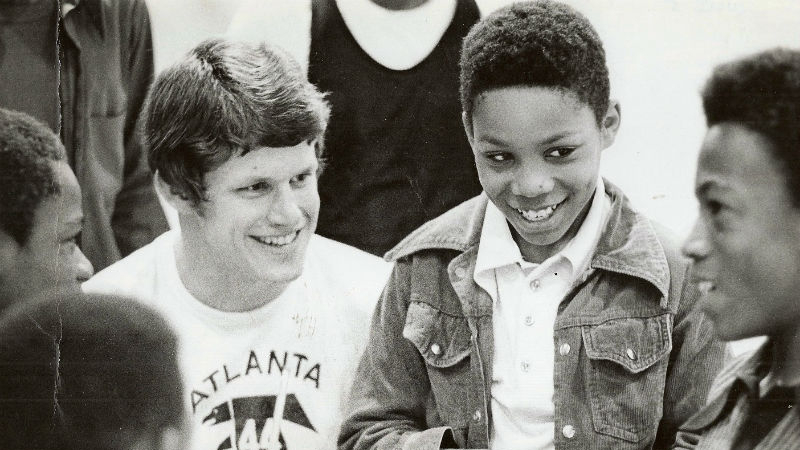

I share that in this context because it is the key to who Ray was when I met him. He was passionate about sharing his faith with anyone who would listen. He went from aimless youth to responsible, leadership on the Falcons’ team. When he returned to Falcons’ training camp that year, a changed man, his coach, Norm Van Brocklin, told him “if you hadn’t changed, we were going to cut you”. Ray believed that God gave him back the very thing that he had always wanted to do.

His passion for Christ led him to speak to youth groups, conferences, and retreats during the football season and all throughout the off-season. He made himself available to anyone who was in need of answers or help.

In January of 1975, Ray returned to Richmond and the Bible study he founded with his dear friend, Earl Nance. It was there that I met him. I was a senior majoring in music at Westhampton College (UR). Ray’s enigmatic personality and genuine faith were magnetic to me. I quickly fell in love with his ready smile, gentle leadership, hunger for God and His Word and gentlemanly ways. I was beyond excited when, even after I graduated and returned home, a dozen roses were delivered. It was at that point that my parents knew that something more serious than just dating was going on!

Ray proposed that summer and we were married on January 3, 1976 in Richmond. It was a fun life of speaking engagements coupled with working out in the off season; working hard to make the team and playing the games during the season. We were newlyweds; very much in love and enjoying our life together.

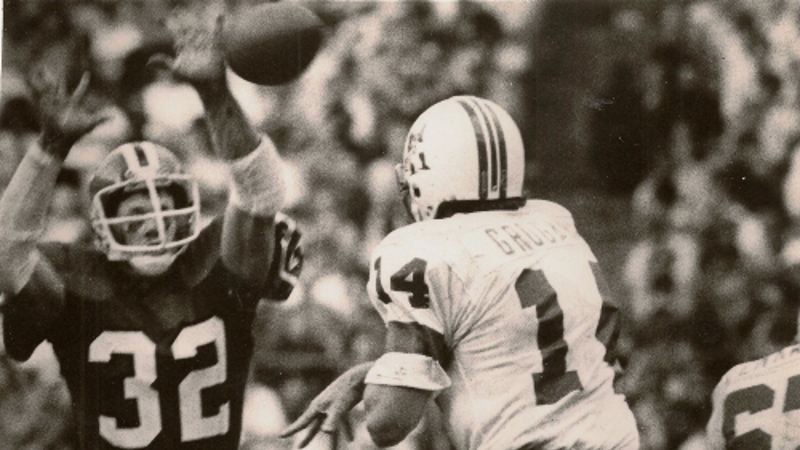

In 1974, Ray started at safety for the Falcons and played through the 1979 season. During his career, he tackled the likes of OJ Simpson, John Riggins and John Cappeletti. His best game was against Walter Payton in October of 1977 where Ray had 20 unassisted tackles and two interceptions. His job was quarterback of the secondary and he reveled in the task of reading the quarterback and communicating with his fellow defensive backs. That year, the Falcons’ “Gritz Blitz” held their opponents to 129 points, an all-time record that has never been broken.

Ray gave his all on the field. There was never a time when he considered loafing or giving less than one hundred percent. Ray never mentioned his concussions. It was a part of the game that no one ever saw except when a player was knocked out. He was seriously injured during the 1978 season with a dislocated elbow. It disabled him to the point where he had to use his head more to tackle.

During his final training camp in 1980 with the Falcons, he shared with me that he was getting stingers and seeing stars a lot. His right thumb went numb and the muscles in his arm began to atrophy. The team trainer took notice when, after not sleeping several nights, Ray asked for a sleeping pill. The trainer also saw the neurological damage apparent in his arm. After a series of examinations and being told that returning to play might bring paralysis, Ray decided to retire from professional football. He saw this as God’s merciful way of showing him that it was time to walk away.

During the 1980s Ray successfully built a financial services business. We enjoyed prosperity to a level not experienced during football. We had investments and a portfolio that would be the envy of most middle class Americans. Ray attributed his success to God’s blessings.

Upon turning 40, Ray began to experience serious problems with insomnia which, in turn, led to depression. He left the financial services business along with its excellent residual income and decided to take a new direction. He tried to start several businesses on his own over the next 9 years. His description of these decisions was “uncharacteristic” and “I didn’t do the due diligence I would normally have undertaken”. I found that I was living with someone I did not recognize. My normally disciplined husband took chances with our finances that ended in losing our house and all our savings.

Interaction with our friends gradually dwindled; he pushed away some very close friends in fits of temper. Ill humor was a constant companion.

In and out of various professions, Ray had difficulty working with others. It wasn’t until he brought his business home in 2007, that I noticed his inability to organize and keep track of details. Never one to tolerate messiness, his desk was a maze of phone messages and incomplete business plans.

I was at a loss to know what had happened to my precious husband. In December of 2010, I saw a blurb on the Internet about a former NFL player who had CTE. It took me to the case studies Drs. McKee, Stern, Cantu and Chris Nowinski had done on former athletes who were diagnosed with CTE. The symptoms and behavior matched Ray’s. I was and am so grateful to them for making their findings known.

The spring of 2011, Ray was diagnosed with dementia due to the concussions he sustained in professional football. We finally had our answer to the questions of “what” and “why.” The feelings of helplessness mounted as Ray’s symptoms worsened. The medicines available could only promise to stave off the march of the disease temporarily.

With the conviction that his time on earth was complete and that he was “ready to meet” his Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ, Ray took his life on April 19, 2012. The subsequent autopsy revealed moderately severe CTE in Ray’s brain.

I hope and pray that sharing Ray’s story has helped you understand what a devastating disease CTE is and how important the work that the Concussion Legacy Foundation and BU CTE Center are doing. Please consider doing all that you can to help in educating your friends and promoting this research.

Most of all, to God, be the glory! For He sustained us through a difficult time with His peace and provision.

Read more about Ray’s story in the New York Times here, and in a Christian Families Today newsletter here.

Dan Ehle

Louie Elias

Troy Ellis

Warning: This story contains mentions of suicide and may be triggering to some readers.

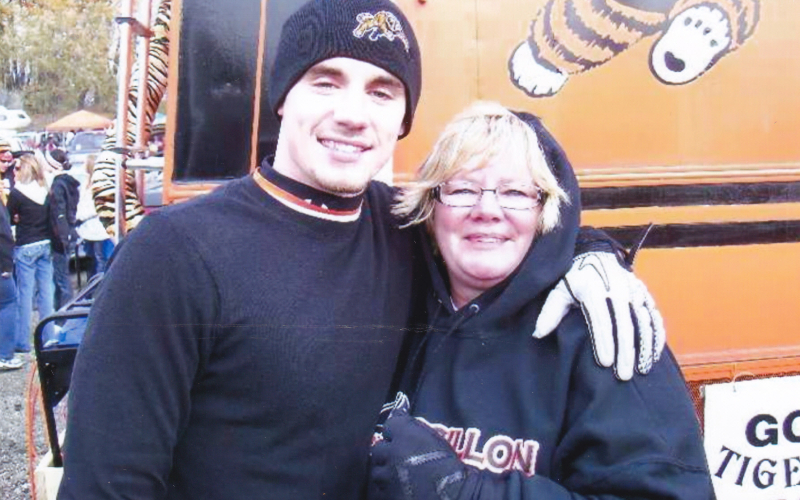

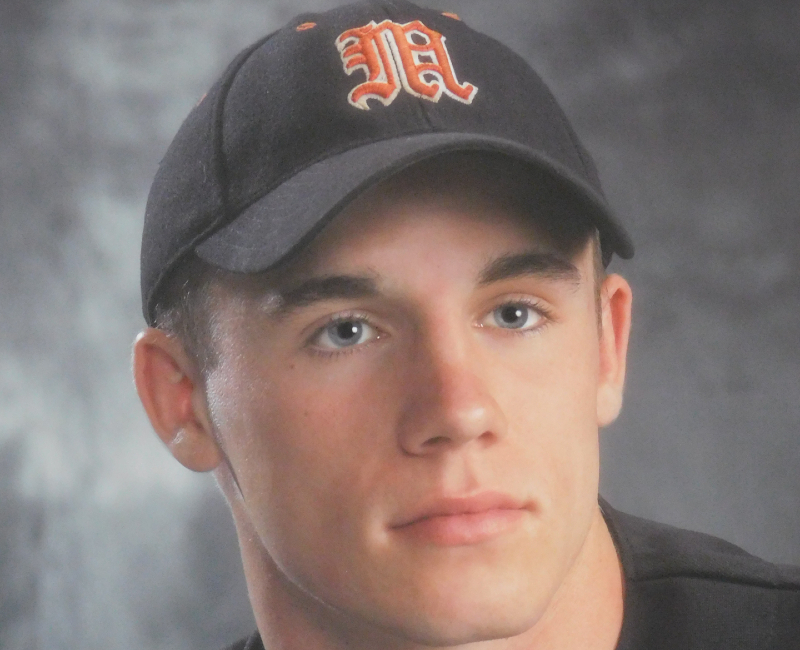

Troy Ellis had a big presence and an infectious personality. He was very handsome and charismatic. The boy could dance too, and he was the life of the party. He was often told how much he looked like Channing Tatum. Troy thought he could play Channing’s younger brother in a movie. He would say, “If I was given a dollar for every time someone told me I looked like Channing, I’d be a millionaire.” He was fun, energetic, lovable, and loved by many. He recited lines from movies on a regular basis, especially from the movie Forrest Gump, which always produced lots of laughs.

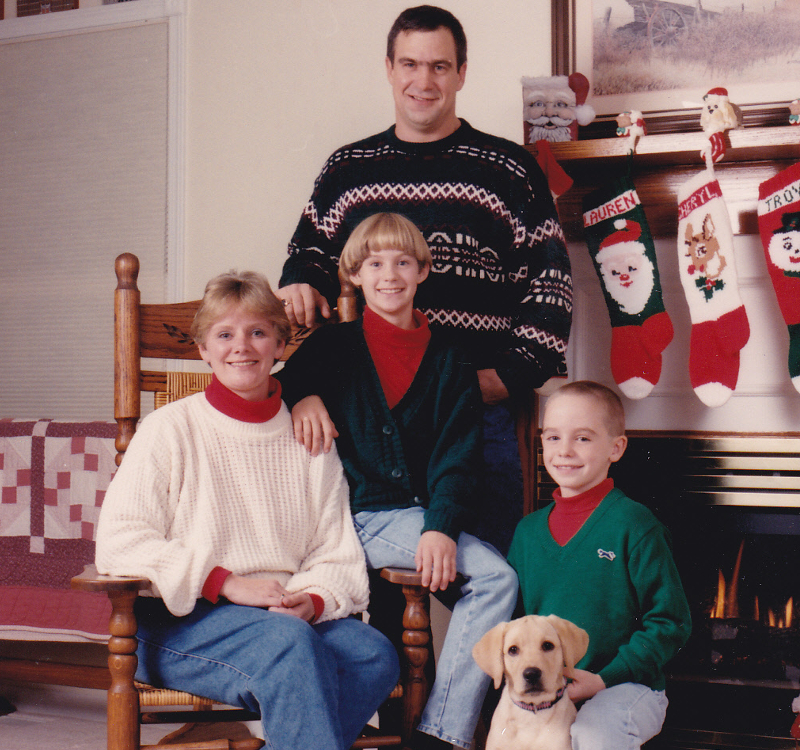

Troy Boy was a natural athlete, showing his abilities very early on in his life. He couldn’t even walk yet but was always reaching for a ball of some sort. When he was two years old, he received a baseball and glove as gifts. He slept with them and called it his “glub.” His older sister, Lauren, was also very athletic. I knew, as well as their father, that we were going to spend a great deal of our lives watching them play sports. They were talented and eager to compete. They made each other better and there were fights along the way. Both were voted “Most Athletic” by their peers in high school. His sister was his hero. Troy was Lauren’s best person and stood up for her when she was married.

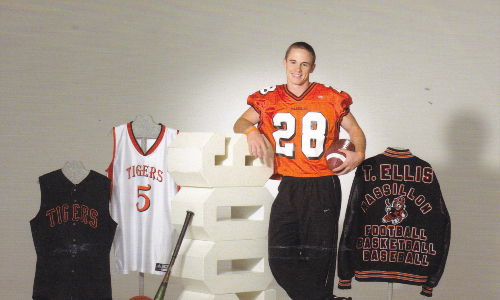

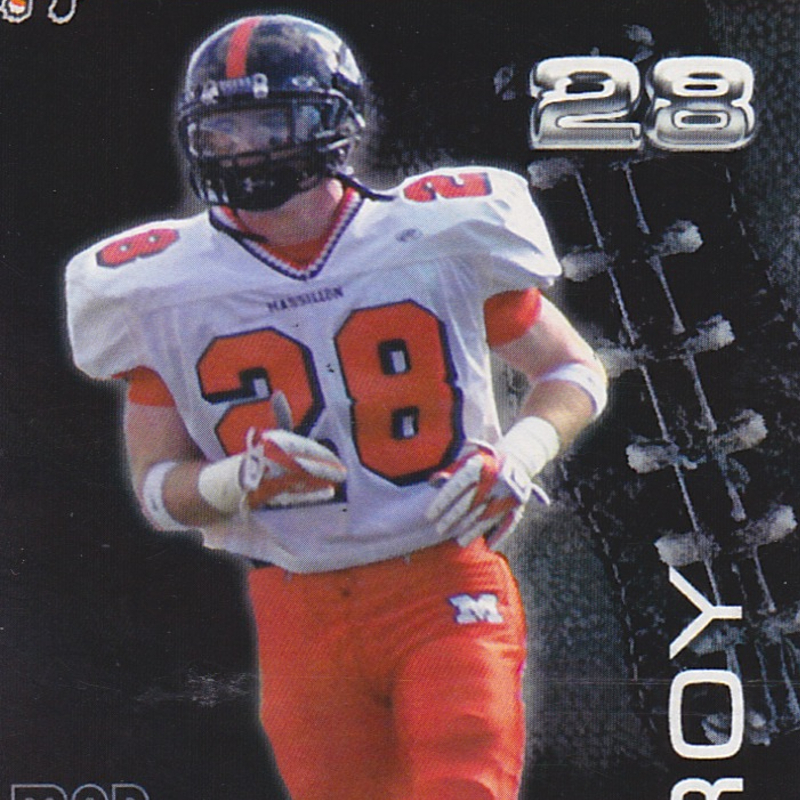

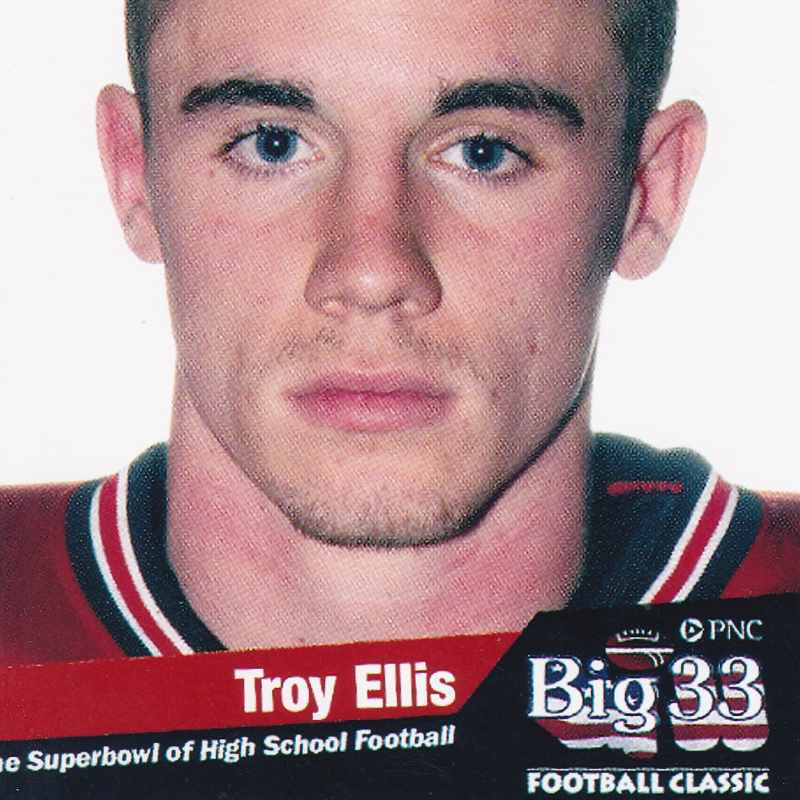

Troy played soccer, basketball, baseball, and of course, football, which he started in the fifth grade. He played for the storied Massillon Tigers in Massillon, Ohio. Football is close to godliness in Massillon. Troy loved the game. You are somebody when you are a Massillon Tiger. Little kids looked up to him and wanted his autograph. He was a three-year starter and never missed a game, playing cornerback, wide receiver, and punt returner. He was second team All-Ohio his senior year and was on the All-Stark County Team. He played in the Big 33 game in Hershey, Pennsylvania in 2006. He was a one-man highlight reel his senior year against Cincinnati Elder at the Cincinnati Bengals stadium. He had five interceptions in this one game (a record for the Massillon Tigers) while also recovering a fumble and returning it for a touchdown. He was named the game’s MVP.

Troy was known as a hard hitter and received the Bob Cummings Hardnose Award his senior year as voted on by members of the Massillon Tiger Booster Club. Former NFL player Chris Spielman also won the same award in the past. Troy received many accolades in the sports he played and he earned them all.

As his mother, I always thought baseball was Troy’s best sport. He was a four-year varsity starter in high school, the first at Massillon since 1975. He played second base and then shortstop. He played for the Stark County Stars in summer ball. A local reporter said, “Troy is the epitome of a leadoff hitter.” He went on to play shortstop at a junior college, Olney Central College in Illinois, for two years. While at Olney, he played a game at Busch Stadium. He also played Class A ball in Kentucky and played for the Canton Terriers.

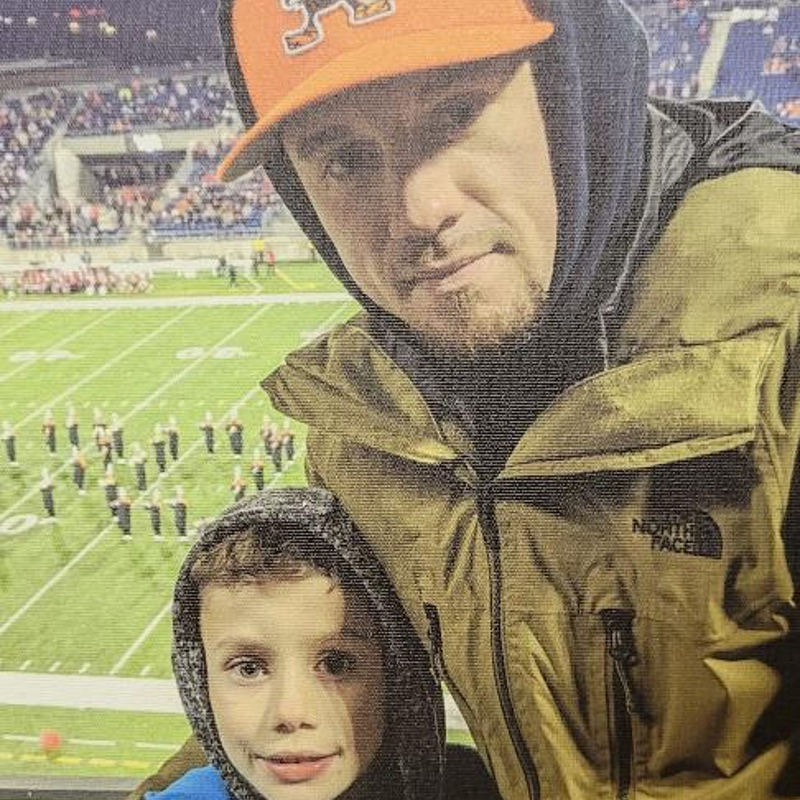

Troy had a son, Ashton, who was 10 at the time of Troy’s death. Troy and Ashton’s mother were no longer together, but he would get Ashton nearly every weekend. He enjoyed teaching him about baseball, football, and basketball. He installed a basketball hoop in his basement for Ashton. They would go fishing, golfing, roller skating, and played laser tag. He also shared his love of music and dancing with his son. Several years ago, Troy bought Ashton a pair of LeBron’s shoes in a large size that he has yet to grow into.

Troy was employed as a third generation plumber and pipefitter out of Local 94 in Canton, Ohio. His coworkers loved working with him. He also helped coach a middle school girls’ basketball team and was often known to lend a helping hand to others.

Troy had multiple head traumas from a young age. He fell out of a wagon and hit the back of his head on the cement floor. He fell off the side of the basement steps. He rode his bike down the deck steps. The front wheel came off of his bike and he fell face first into the sidewalk. The worst head injury was when he fell out of a tree at age eight and had a brain bleed. That was the worst day of my life, until the day he died. He was in the ICU for three days and in the hospital for a week. In time, he recovered and was cleared to continue playing sports. Additionally, he took a nasty pitch to the left side of his face while playing college baseball.

I would say around 2014 is when we started noticing changes in Troy’s behavior. He was very forgetful, erratic, angry, and engaged in risky and impulsive behavior. He started to struggle with life in general, including with money and getting in trouble with the law. He had relationship issues with family members, friends, and with women. In hindsight, I don’t think he was capable of settling down due to the CTE. I was so worried about him all the time. By 2020, the only thing predictable about Troy was his unpredictability.

In the early morning hours of December 26, 2021, Troy was believed to be the person who started a fire at his girlfriend’s home. The house was destroyed but fortunately no one was home at the time. Several hours later I received a call to go check on him. I did and he was distraught like I had never seen him before. He would not let me in the house. Shortly thereafter, he shot himself in the chest. As he was being loaded into the ambulance, he told me he was sorry. I could not see where he had been wounded but asked him if he was OK. He said, “I’m gone.” He told the paramedic to tell me he was sorry, that he loved me and this wasn’t my fault. He made the paramedic promise to tell me. Troy died three hours later. We did not get a chance to see or talk to him again.

The Massillon Tiger Community honored him after his death. Bracelets were made and sold with his football number on them and engraved “#28 Forever T.E.” Baseball hats were made with his number, as well as jerseys with a picture of Troy on the inside of the back of the neck. This way, Troy could “have their back.” Family members started a crowdfunding and all of the funds are being held for his son. The person at the mall who made the hats said, “We have made so many of these hats in memory of Troy Ellis. He must have been someone very special.”

I need to emphasize that I am not attempting to glorify Massillon Tiger football. I’m simply telling a true story about my son and his history of being a Tiger. Massillon football fans tend to over glorify their players. The kids are put on a pedestal and it’s just too much at times. The players in this program are more revered than those at most college programs. Many players have gone on to college and it has been a big letdown for them. I look at football through a totally different lens now.

After Troy’s death, his brain was donated to the UNITE Brain Bank, where researchers diagnosed him with stage 1 (of 4) CTE. Had I known more about CTE, I would never have allowed him to play football. I have learned so much more about CTE and the devastating consequences it brings. I would never advise anyone to play football, or any sport suspected of causing CTE. His glory days turned into his gory days because of CTE. Simply put, the glory days were not worth it. I strongly urge parents to do their own research into CTE and make wise choices for their children, including supporting CLF’s Stop Hitting Kids in the Head. I certainly wish that I had. It’s too late for me now.

Troy said to me, later in life, “Football is a violent game, played by violent men.” After he passed, we were told that Troy had shared with others that he had “demons in his head and he was scared for himself.” He also said there was something wrong between his ears. He never shared that information with us.

We are all devastated and continue to carry a heavy load of grief, and the guilt that comes along when a loved one takes their own life. We love and miss him constantly.

Suicide is preventable and help is available. If you are concerned that someone in your life may be suicidal, the five #BeThe1To steps are simple actions anyone can take to help someone in crisis. If you are struggling to cope and would like some emotional support, call the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988 to connect with a trained counselor. It’s free, confidential, and available to everyone in the United States. You do not have to be suicidal to call.

Are you or someone you know struggling with lingering concussion symptoms? We support patients and families through the CLF HelpLine, providing personalized help to those struggling with the outcomes of brain injury. Submit your request today and a dedicated member of the Concussion Legacy Foundation team will be happy to assist you.

James “Jimbo” Elrod

Andrew Erker

The morning of January 11, 2017 started out just like any other morning. Andrew got out of bed early to send me off to work with a big hug, kiss, an “I love you” and his typical, “Whatever you do today, just be a good person.”

Andrew’s number one priority in life was to be a good person regardless of the circumstance. He never failed to live up to that standard he set for himself. I would always receive a text late morning just to check in and see how my day was going. Not hearing from him at all that day in January made me a little uneasy. Driving home from work that night I knew in my gut something was very wrong. Andrew died by suicide earlier that day in our home.

This horrific tragedy came as a massive shock. Surely that wasn’t him. It didn’t make sense. Andrew had such a love for family, his friends and me. His enthusiasm for life, nature and wildlife was unmatched. He would light up a room with his smile. Andrew was the most selfless man I had ever known. His intentions to make everyone happy and be a better version of themselves were as pure as they come.

Something in his brain was not right that day and hadn’t been for a long time. Andrew was not the type to complain or ask for help. He refused to burden or worry anyone. He wanted to do it all himself and was determined to do so. I believe he suffered internally for longer than I knew or could ever imagine. Andrew’s sense of humor was one of his best qualities. He was constantly making everyone around him smile and laugh. For as long as I knew him he would joke about football messing up his brain. He believed it made him “stupid” even though he was thriving at work and nothing about his daily life made it seem like he was missing a beat. Joking about it I believe was his way of trying to tell me something wasn’t quite right without making me worry. When Andrew and I started talking about having a family his number one rule was that our kids would not play football. It was becoming clear to me that he was truly worried about the toll football took on his brain.

Andrew and I met at a bar in Kansas City in 2014. I was 22, still in nursing school and he was 27 living in Lincoln, Nebraska. He was home for a weekend and out with friends when we met. From the moment I met him I knew he was incredibly special and early on we both knew it was meant to be. He moved back to Kansas City the following year and we were married in April of 2016. Nine months later he was gone.

Andrew played tackle football from the time he was a child through his college career at Kansas State University, where he played safety. Andrew was not the biggest player on the field, but he was tough and known for his hard hits. I believe Andrew suffered several undiagnosed concussions during his time playing football. He told me about several games he didn’t remember after playing in them and times where he just didn’t feel quite right after games.

A few months before he died, I started noticing the forgetfulness. He couldn’t recall certain conversations or plans we made. Towards the very end of his life he became more irritable and his patience was diminishing. Although his anger seemed to be heightened in the last couple weeks of his life, I do feel as though his emotions were fairly well controlled. It seemed as though Andrew was somehow able to mask many of the typical signs and symptoms of CTE.

Andrew’s family and I decided right away to donate his brain based on his football history and his recent behavior. Andrew was always helping others so when donation became an option I knew he would jump at the chance to try and help save someone else’s life. Boston University was an obvious choice for us, and I could not be more grateful for how we were treated and supported during this incredibly difficult time. I felt as though Andrew was respected and appreciated by the researchers from the UNITE Brain Bank from day one. Seven months after he died, Andrew was diagnosed with Stage 3 (of 4) CTE. We were all shocked to see such advanced disease in a 30-year-old.

I want people reading Andrew’s story to understand the dangers and possible effects playing tackle football as a young child can have on your brain and your life. I want people to know that CTE can happen to anyone with a history of repeated head impacts like Andrew had. Choosing to put your child in tackle football at a young age could end up destroying their life and leaving their loved ones completely devastated. I know Andrew would have much rather sacrificed his football career for his life than his life for his football career.

I feel incredibly lucky to have fallen in love with a man who I know fought like hell against an uncontrollable brain disease to protect his friends and family.

__________________________________________________________

Suicide is preventable and help is available. If you are concerned someone in your life may be suicidal, the five #BeThe1To steps are simple actions anyone can take to help someone in crisis. If you are struggling to cope and would like some emotional support, call the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988 to connect with a trained counselor. It’s free, confidential, and available to everyone in the United States.

Are you or someone you know struggling with lingering concussion symptoms? We support patients and families through the CLF HelpLine, providing personalized help to those struggling with the outcomes of brain injury. Submit your request today and a dedicated member of the Concussion Legacy Foundation team will be happy to assist you.