Kendal Keys woke up on July 26, 2018, and said enough was enough. He had been trying to see his older brother Kenny for months but the two failed to connect despite both being in Las Vegas. This time, he didn’t give Kenny a choice – he picked him up and drove to their dad Kenneth Sr.’s place for dinner.

With Kenny in tow, Kendal blasted Chance the Rapper’s “Blessings.” Kenny was dozing off, but Kendal couldn’t stop smiling.

“I was just happy because he was with me,” Kendal remembers.

At one point on the drive, Kendal asked Kenny a simple question. Kenny delivered a completely incomprehensible answer. Kendal’s heart sank. He had seen this before.

The two arrived at their dad’s place and Kendal walked into the bathroom and looked himself in the mirror. We can do this, he told himself. It was too late to take Kenny back to his psychiatrist that night, but he would plan to take him there first thing in the morning.

Kenneth Sr., Kenny, and Kendal enjoyed each other’s company over dinner. Kenny and Kendal were back laughing at and with each other like they had their whole lives. Kendal offered to step out and get some water bottles for everyone, hoping to get Kenny back in the car so they could discuss the need for an appointment the next day. Instead, Kenneth Sr. offered to come along and Kenny opted to stay behind.

At Walmart, Kendal and Kenneth Sr. ran into a family friend who told them to say hello to Kenny for her. Father and son both remarked on the breathtaking sunset above the mountainous Las Vegas horizon on the drive home.

When they opened the door back at Kenneth Sr.’s place, Kenny wasn’t where he’d been when they left.

“As soon as I didn’t see him on the couch, I just knew he was dead,” Kendal said. “I didn’t know how but I just knew he was gone.”

“You only got one Kenny.”

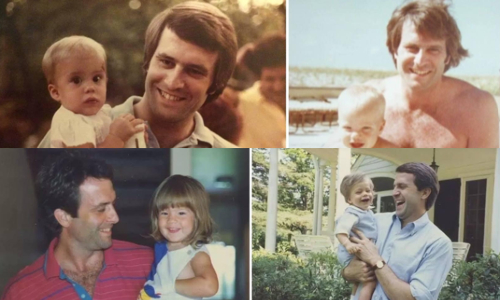

Kenny Keys, Jr. was born on February 25, 1993, to Kenneth Keys Sr. and Syvonne McNair in San Diego, California.

Kenneth Sr. grew up in Florida as one of 13 children. He loved watching his Miami Dolphins on Sundays but Kenny’s energy as a toddler often got in the way.

“I would make him run down the hallway,” said Kenneth Sr. “When I’d say, ‘Go!’ he would run down the hallway and around the living room. It was the only way to tire him out and he’d just fall asleep.”

From a young age, Kenny exhibited a coolness with everything he did. People gravitated to him.

“Teachers would tell me how Kenny had a smile that could stop a bus,” Kenneth Sr. said.

Kenneth Sr. was a correctional officer for the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation and then a prison counselor. He often made visits to school to speak to students. Kenneth Sr. was a former college basketball player with the height to prove it. Kenny used his dad’s height to manufacture an autograph line full of kids who were convinced his dad played in the NBA.

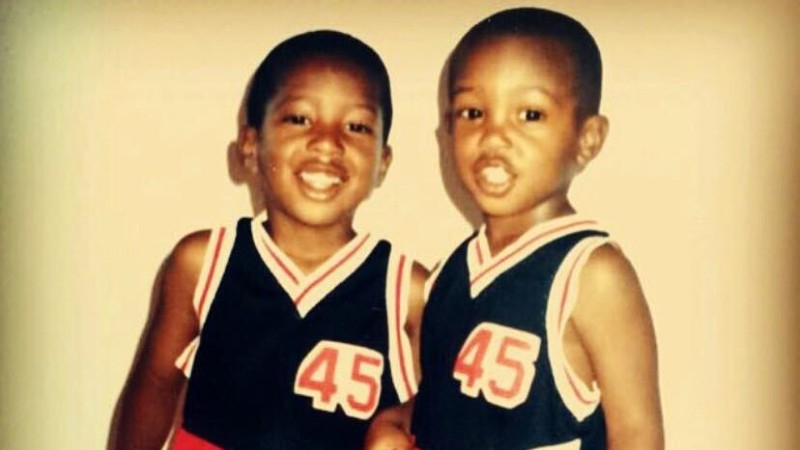

Kenny’s mother Syvonne also worked in law enforcement. They called Kenny “The Judge” because he could always see right from wrong and settle disputes between his siblings, Kendal and Kaitlyn. Kendal was born less than a year after Kenny and then Kaitlyn came five years later, in 1999.

Kendal had the benefit of following Kenny’s lead and the curse of trying to fill his shoes.

“He was the complete role model,” Kendal said. “He knew that I needed guidance and everywhere I went he always told me where to go.”

“Effortlessly cool.”

The Keys boys were two peas in a pod, always playing sports together. Kenny usually won and he’d let Kendal know all about it, which led to a near-constant cycle of playing, fighting, and making up.

Throughout life, it wasn’t just losing to Kenny that irked Kendal. It was how easily everything came to Kenny.

“He didn’t even want to be prom king and he won prom king,” Kendal said. “He didn’t have to try. I was the one who had to try all the time to be liked or whatever.”

The boys ran track, played basketball, and starting in 2006, played middle school football. It was there that Kenny developed a reputation for laying out heavy hits to opposing receivers and nonchalantly walking away from the damage afterwards.

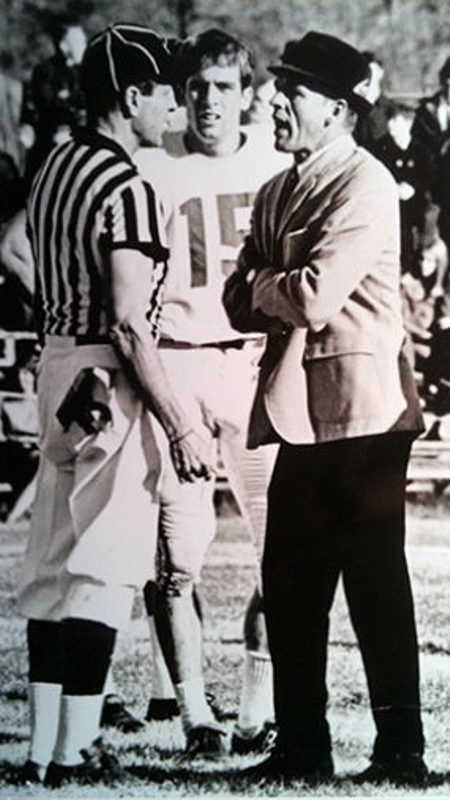

At Helix High School, Kenny continued to star in track and basketball and didn’t play football until he was a senior. At tryouts that year, the coaches challenged him with a one-on-one drill against one of the team’s biggest players. Kenny knocked him out cold. With Kenny as a starting safety, Helix went 12-1. Kenny’s play in just one high school season earned him a Division I scholarship offer from UNLV.

44 Magnum

In his first football season at UNLV, Kenny picked up where he left off at Helix. He appeared in all 13 games, starting five, recorded 45 tackles and two interceptions wearing No. 44 for the Rebels. The hard hits continued and earned him a new nickname. “The Judge” was now “44 Magnum.”

Kenny made the Dean’s List that year and returned to Helix High to catch one of Kendal’s games. Kendal knew his big brother was in the stands and caught the first touchdown of his career. As he came off the field, Kendal was surprised to see Kenny come all the way down to the sideline to celebrate.

“He wanted us all to better ourselves,” Kendal said. “He wanted everyone to be successful. He didn’t hate on anybody.”

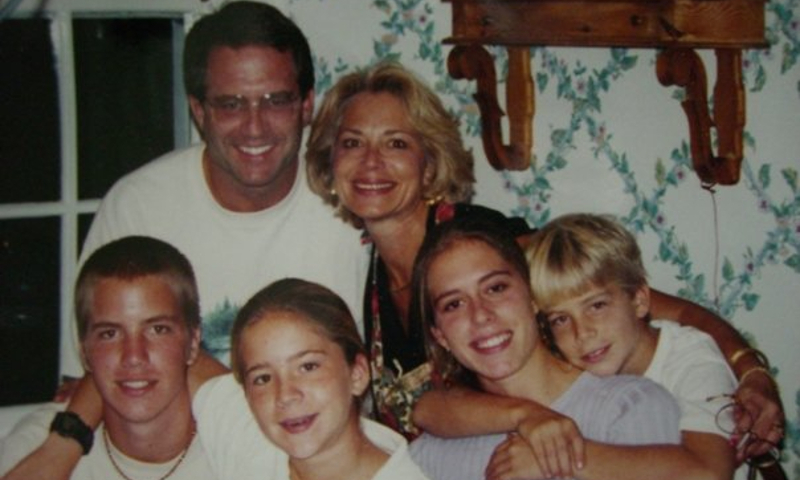

Kendal blazed his own trail as a receiver at Helix and earned the attention of college scouts. Initially, he had no interest in playing with Kenny at UNLV. He was more attracted to the bigger stage and bluer turf of Boise State and signed to play there in 2013. Local papers in San Diego wrote about the impending matchup of the Keys brothers in the Mountain West Conference.

But Kendal’s career in Boise was over before it started. After enrolling in fall 2013, he was expelled from the school. The expulsion marred Kendal’s chances of enrolling elsewhere, but Kenny convinced the UNLV coaches that Kendal was more than his mistakes. They took Kenny’s word and Kendal signed with UNLV, thrilled with the opportunity to play college football with his big brother.

With Kendal now set to move in with Kenny, Syvonne warned Kendal that she had noticed something was off with his brother. At first, Kendal didn’t see what she was talking about. If anything, Kenny seemed like he was back at Helix. Everyone loved him and once again, Kenny was showing Kendal the ropes on campus.

But slowly, Kendal noticed what his mom was describing. Typically, Kendal couldn’t be around Kenny for more than ten minutes without busting out laughing at something he did or said. But this Kenny was quiet and more distant. Kendal frequently caught him staring off into nothing.

The behavior affected his standing in school and on the UNLV team. Kenny was routinely late or completely absent from spring and fall camp. He barely played his sophomore season.

Kenny would also say bizarre and alarming things to Kendal. He once joked that Kendal should drink Drano with him. Fearful Kenny would hurt himself, Kendal never let his brother out of his sight. But once, after Kendal took a nap, he woke up to find Kenny gone. He returned three hours later. When asked where he was, Kenny flatly told Kendal he went to the Vegas strip and considered jumping off a building.

“We gotta get you out of here.”

Kendal knew something was wrong but shouldered the burden of trying to fix his brother. He wouldn’t tell his mom everything because it would have led to dozens of calls a day. He wouldn’t tell Kenneth Sr. for fear of disappointing the father who cherished his children’s successes.

“It was like we were always the trophies,” Kendal said. “We were always on a sports team and his friends would come to see us. So, we felt like we didn’t want to ruin that.”

Kenneth Sr. tried to connect with Kenny, but his calls went unanswered. Kendal always picked up but kept details about Kenny to a minimum. In October 2013, Kenny’s internal battle reached a breaking point. He finally called his father back.

“Dad, I need your help,” Kenny said.

Kenny had just left a psychiatric hospital he was admitted to after trying to take his life.

Kenneth Sr. started corresponding with members of the UNLV coaching staff. He set a meeting with UNLV head coach Bobby Hauck in November 2013 to discuss Kenny’s progress. Kenneth Sr. asked his sons to join him for the meeting, but only Kendal showed up. Hauck informed Sr. that Kenny completely flunked out of the fall term at UNLV. He could maintain his scholarship if he returned to school in January.

Kendal had to tell his father that Kenny missed the meeting because he was in a psychiatric hospital again after making a second attempt on his life.

Kenneth Sr. took his rental car to the hospital to find a heavily sedated Kenny. Kenneth Sr. couldn’t stand to see his beloved son with the bus-stopping smile medicated to the point of looking like a zombie. He combed Kenny’s hair and promised to do what it took to get him out of the hospital.

Kenny was on heavy doses of medications to keep him calm. At the facility, doctors would test different drugs on Kenny until they found what worked. Kenneth Sr. took Kenny to all his meetings and visited him frequently throughout his stay. He was released in January 2014.

Kenny was diagnosed with major depressive disorder and psychosis, as well as marijuana and amphetamine abuse. Psychiatrists concluded Kenny’s sudden onset of symptoms may have been triggered by marijuana use and THC.

He made it back before Hauck’s deadline, but UNLV and the NCAA would have to see Kenny’s psychiatry report before clearing him to play. Kenneth Sr. assumed there was little chance they would deem Kenny eligible to keep playing. But they did.

“If they only looked in our eyes.”

With Kenny out of the hospital, Kendal had his brother back. Kenny was quieter than before but more importantly, stable. As his dosage of medication lessened, Kendal saw someone closer to the old Kenny return. In conversations about the last few months, Kenny didn’t remember the suicide attempts or any of the alarming things he said to Kendal.

With Kenny cleared to play, the Keys brothers could finally share the same field at UNLV. On Kendal’s first day of practice in spring 2014, none of UNLV’s receivers were eager to step up to Kenny in a one-on-one drill. Kendal never balked at an opportunity to prove himself and volunteered. He was quickly humbled by his big brother. In another drill, Kendal caught a pass and was running across the middle of the field before being stripped from behind. Kendal knew how much his coaches hated fumbling and was ready to blow up on whoever stripped him. But he turned around to see a smiling Kenny.

“I’ll never forget that,” Kendal said. “My brother is really out here. We have the same parents, now we’re on the same team.”

Their first season together offered a glimpse at a bright future. Kendal broke on the scene with 24 catches as a true freshman and Kenny recorded 42 tackles, many worthy of the “44 Magnum” moniker.

Kenny suffered two diagnosed concussions in his football career, and his family thinks many undiagnosed ones as well. He often said he finished games without knowing what half the game was in or where he was. Not only did Kenny’s nonchalant nature after big hits potentially hide concussion signs, Kenny also learned from a teammate to keep his helmet on when he was on the sideline so nobody could see his eyes.

Kenny saw a psychologist with some frequency since he returned to UNLV in 2014. But in his junior year, Kenny called his dad again.

“Dad I feel like I’m hurting everybody,” Kenny said.

Kenny again expressed thoughts of self-harm. Kenneth Sr. insisted there were countless people who loved Kenny and needed him to be strong.

Despite his unquestioned ability, Kendal says the coaching staff didn’t love giving Kenny playing time. He was routinely outworked in practice and in the weight room and coaches gave starting jobs to other players. But when UNLV went down in games, Sr. says Kenny was brought in to clean up the mess. On multiple occasions he led the team in tackles despite not starting the game.

Kenny’s fifth and final season at UNLV in 2016 was his brightest. He recorded 66 tackles and five pass deflections.

The 2017 NFL Draft came and went without Kenny’s name getting called. An AFC East team was interested in signing him as an undrafted free agent, but Kenny was still recovering from shoulder surgery and the team passed on signing him for the time being.

While Kenny wouldn’t be playing professional football, he had plenty to celebrate. After high school, Kenneth Sr. challenged Kenny. Plenty of people go to college, but the real achievement was graduating. After Kenny graduated from UNLV, Kenny went straight to his father with his degree.

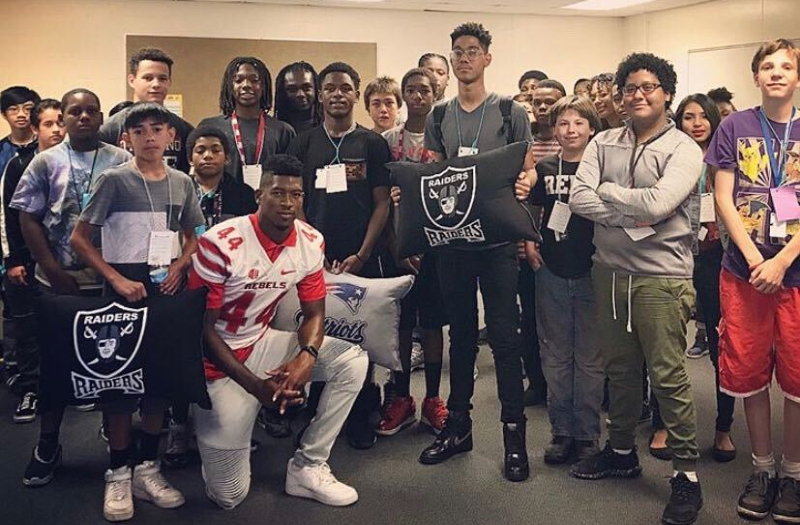

Kenny studied education and sociology. He had ambitions of being a mentor for the next generation and was a beloved volunteer at Paradise Elementary School in Las Vegas.

Kenny was frustrated at not being able to find a job immediately after graduating. He worked at a warehouse and stayed in shape for a potential shot at the NFL. He got a boxer named Cali who was glued to his side. Kenneth Sr. moved to Vegas in May 2017 and noticed Kenny seemed down at times, but he was always talkative and invigorated whenever he was around Cali.

One afternoon in July 2018, Sr. came by the warehouse to deliver Kenny’s favorite homemade meal of collard greens, cornbread, and ribs. When he dropped off the food, Sr. noticed Kenny looked drained.

Sunset

Kenneth Sr. and Kendal will never forget the sunset they saw on their drive back to Kenneth Sr.’s home on Thursday, July 26, 2018 and the memory it triggers.

They arrived back that evening with bottles of water and the Pepsi Kenny asked for. When Kenny wasn’t immediately in sight upon arrival, Kenneth Sr. assumed he was using his master bathroom on the left side of the house. Kendal had an ominous feeling about where Kenny was and made a beeline to the bedrooms on the right side.

Moments later, Kendal left the room and yelled in agony to his father. Kenny had taken his life. He was 25 years old.

“I could see the pain that he was going through.”

Sr. sought answers after Kenny took his life. When Kenny’s toxicology report came back negative, he found relief in knowing Kenny did not have any drugs or alcohol in his system upon his death.

His search for answers then led him to the UNITE Brain Bank, when a member of UNLV’s athletic department gave Kendal a tip for Kenneth Sr. to call the number for brain donation. Sr. obliged.

Before the tip, the family hadn’t considered how Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) may have played a role in Kenny’s story. CTE is a degenerative brain disease found in athletes, military Veterans and others with a history of repetitive brain trauma.

Dr. Ann McKee, Director of the Brain Bank, performed the pathology report on Kenny’s brain. She detailed her findings to the Keys family on a call. Kenny had Stage 1 (of 4) CTE.

“The way that Dr. McKee explained it, I could see the pain that he was experiencing,” Kenneth Sr. said. “That doesn’t explain why he did what he did, but I can see why he was hurting.”

Early symptoms of CTE typically appear in a patient’s 20’s or 30’s and can include depression, aggression, paranoia, impulse control problems, and suicidal thoughts. The connection between CTE and suicidality is still unclear to researchers but it is part of ongoing research at the UNITE Brain Bank. Research has shown a link, though, between concussion and suicide risk. One study found those who suffer a concussion are twice as likely to take their own lives.

On their last drive together, Kenny told Kendal how excited he was to watch him finish his football career at UNLV. With a year of eligibility left, Kendal chose to keep playing. He joined the Rebels at fall camp a week after Kenny’s death.

“Kenny is suffering that much and in that much pain, but he’s thinking about me playing?” said Kendal. “I needed to get back out there.”

They played different positions, but Kendal exhibited a similar physicality and reckless abandon to Kenny. After Kenny was diagnosed with CTE, Kendal realized how important it was for football players to take care of their brains.

“Speak up about concussions,” Kendal said. “If you are feeling some type of way about your head, don’t let your ego get in the way. Because it could cost you your life.”

Kenneth Sr. echoed those thoughts with a message to parents.

“After a couple of concussions, you want to err on the side of caution,” Kenneth Sr. said. “Go ahead and remove them from that sport. Better to have them here than to not have them here.”

Kenny meant a lot to so many. Many of his former teammates chose to memorialize him through tattoos and custom jewelry.

Torry McTyer played in the defensive backfield and was good friends with Kenny at UNLV. He was in training camp with the Miami Dolphins when he heard Kenny took his life. In response, McTyer and his family raised thousands of dollars for the Keys family. In the 2018 NFL season’s “My Cause, My Cleats” week, McTyer chose suicide prevention as his cause with cleats that said, “In Memory of Kenny Keys.”

“You always feel like you could have done something different,” McTyer said in a story for MiamiDolphins.com. “It’s a helpless feeling. But I want people to know who Kenny Keys is. I want people to realize that things like this are happening everywhere and they can be prevented.”

After she lost two of her children, Kenneth Sr.’s mother once told him there was no pain like losing a child. He now can understand his mother’s grief. He has focused his attention on trying to protect other parents from his tragedy.

“I spent 26 years saving people’s lives and I couldn’t save my own kid,” Kenneth Sr. said. “I’ve got to help somebody. If I could just help one kid, save just one kid’s life, or educate some parents and let them know how serious these concussions are then I’ll be good with that.”

Kendal internalized guilt for Kenny’s suicide for a long time. He dreams about Kenny nearly every night, always imagining the two of them laughing and being goofy together.

He wants to honor Kenny’s legacy by encouraging other athletes to seek mental health resources and be honest about their symptoms. He implores anyone struggling to reach out and when they do see a mental health professional, to bring someone with them who can speak to their issues and eliminate the chances of getting misdiagnosed.

“When you go get help, don’t go in there knowing or demanding or trying to think you can do it yourself,” Kendal said. “Let the professionals do what they’re paid to do.”

Kendal has joined our roster of mentors for the CLF HelpLine. He hopes to be a resource for other football players who are battling the effects of concussion or struggling with their mental health.

When Kenny left the psychiatric hospital in winter 2013, he gave his Helix High letterman’s jacket to his dad.

After Kenny died, Kenneth Sr. found the jacket again. In one of the pockets, Kenneth discovered a folded handwritten note Kenny wrote while in the hospital thanking his dad for everything he had done for him. Kenneth Sr. He holds the note and the memories of Kenny tight.

“He was a good kid, man,” said Kenneth Sr. “He was special.”

Suicide is preventable and help is available. If you are concerned that someone in your life may be suicidal, the five #BeThe1To steps are simple actions anyone can take to help someone in crisis. If you are struggling to cope and would like some emotional support, call the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988 to connect with a trained counselor. It’s free, confidential, and available to everyone in the United States. You do not have to be suicidal to call. If you’re not comfortable talking on the phone, consider using the Lifeline Crisis Chat at www.crisischat.org.

If you or someone you know is struggling with concussion symptoms, reach out to us through the CLF HelpLine. We support patients and families by providing personalized help to those struggling with the outcomes of brain injury. Submit your request today and a dedicated member of the Concussion Legacy Foundation team will be happy to assist you.