“J LEE”

Our family is very grateful and honored to have the opportunity to share the life of Jeremiah Lee as a donor to the UNITE Brain Bank.

The extraordinary thing about death is that it honors one’s life. In life, Jeremiah believed he had no honor. In death just the opposite is true. We’d like to think, that had Jeremiah known or believed the truth, he would not have done what he did, or at least would not have been so hard on himself. Jeremiah left this earth way too soon, as he felt his life was no longer worth living. He somberly thought he had let down every person that he loved. He was embarrassed by his actions, by his dependency on alcohol, and for the way his life had evolved; for he knew his life originally had great promise and purpose.

We were the typical “sports family” taking in football, wrestling, and baseball; in between sports we shared hunting, fishing, horse riding, and raising cattle. Jeremiah loved sports, especially football and wrestling, and because of his love he excelled as an athlete.

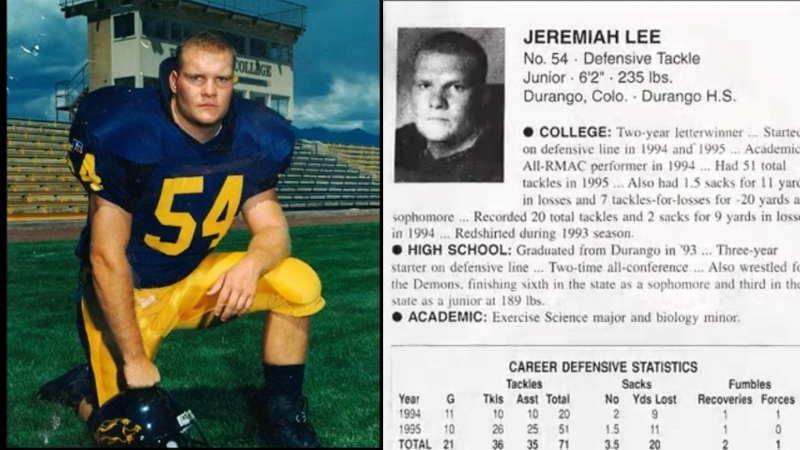

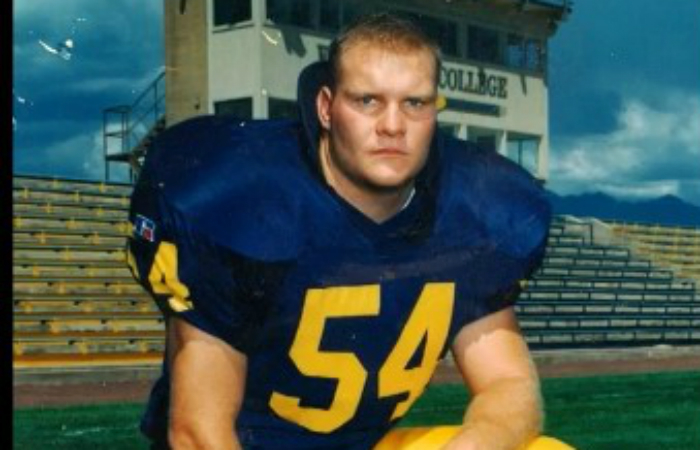

Karl Mecklenburg of the Denver Broncos was his role model, but his one true paradigm was his father; Wayne Lee, played Defensive Tackle in high school and at the University of Northern Colorado. In 1960, Wayne was drafted by the Denver Broncos as a Guard. Jeremiah took in all of the knowledge, instruction, and coaching his father had to offer and was a natural from day one. Even though Jeremiah wasn’t big in stature he followed in his father’s footsteps and played Defensive Tackle. Jeremiah played football wholeheartedly through middle school, high school, and earned a football scholarship to Ft. Lewis College in Durango, Colorado. During his senior year at Ft. Lewis he coached the line of his college team. He was a natural team leader on the field and on the mat. He was very well respected by his teammates, as well as players from the opposing teams. He took the hard hits on the line, and he hit back twice as hard. He never ever quit; he would take the hard hits that “rung his bell”, and would get right up, continue on with the game, and push through his pain. His football buddies said, “Jeremiah hit so hard that no one wanted to go up against him for they knew they were going to get hit, and hit hard!” His friends endearingly called him “J Lee”.

Jeremiah graduated from Ft. Lewis College in 1998 with a bachelor’s degree. In between his Junior and Senior years at Ft. Lewis, Jeremiah attended Trinidad College to get his training and certification in Law Enforcement. Upon graduating the police academy, he was hired by the City of Durango Police Department and served 18 years on the city force. He then moved on as a deputy for the La Plata County Sheriff’s Department. During this time he served as a School Resource Officer, obtained the rank of Sargent, married and had 3 children, coached middle school football for several of the years, and became the “sports and 4-H dad”; he deeply and dearly loved his children. Jeremiah received several honors as Officer of the Year, and just months before he died Jeremiah was honored by the Colorado Cattleman’s Association as Officer of the Year for the Sheriff’s Department.

As a child and young adult, Jeremiah loved life. He loved to cook, and created his own recipes. He was an avid hunter and fisher, also taught by his father, and was extremely passionate about the great outdoors. Although he was a true man’s man, he was a gentle giant. He never passed up an opportunity to share his love of nature with his comrades, and although his life was busy and hectic he was always very dedicated and committed to his friendships; he never let anybody go by the wayside, not even his elementary and high school friends. Jeremiah also never passed up an opportunity to go out of his way to lend a helping hand whether it be a stranger, a family member, or a friend.

The truth is, all whom encountered Jeremiah loved and respected him. Jeremiah knew no stranger; he strived to, and more often than not made friends with each and every person he acquainted. He was well known, respected, and loved by his entire community. In the “good cop, bad cop scenario”, Jeremiah was the “good cop”. He always gave everyone the benefit of the doubt, and in a crisis/emergency situation he readily put all others before himself, and literally gave the shirt off his back. He was not trying to be a hero; he never thought of himself as such, it just came natural to him. 8 months prior to his death he was in a head on collision; and although he sustained very serious injuries and yet another head trauma his concern was not for himself, but for the other driver. He readily went into “football mode”, and managed to squeeze himself out of his badly crumpled squad car in order to rescue the driver that had swerved into his lane. Her family deemed him a hero on that snowy day, and publicly recognized Jeremiah as her “guardian angel”.

Despite all the respect Jeremiah earned from sports and his community, his most defining moment seemed to be the overwhelming life changes he faced all at once; the loss his father, losing his job with the city, and a divorce. He felt like a complete failure and his dependency on alcohol became increasingly prevalent. He seemed to be scatter brained; going from one task to the next, never completing anything. He undoubtedly had lost his love for life. All of us close to Jeremiah witnessed the most drastic change in his last few months; an escalating change, spiraling all too quickly out of control. Suffering from depression and PTSD; his memory failing, his paranoia and anxiety palpable, his hallucinations became his reality. Outbursts of impulsiveness and anger caused great distress, and Jeremiah seemed to no longer distinguish reality from truth. The changes were so significant that the question of CTE was raised by his closest college football buddies.

Jeremiah; our beloved son, brother, father, uncle, and friend left this earth on October 13, 2017; one day before his 43rd birthday. The outpour by his community was most incredible. One of the most profound events ever witnessed in the small town of Durango was Jeremiah’s memorial service. Two massive fire engines; ladders towering into the sky and toward one another suspended, in all enormous glory, the pride of our nation’s flag. Down below; in full dress uniform, all branches of first responders stood at attention with heads solemnly bowed, silent with upmost reverence. They lined both sides of the long path that lead his family into the gymnasium of the college where Jeremiah had graduated 19 years before. Friends, and family packed the stadium to give due honor and tribute to his life.

Jeremiah Lee was a very proud, yet humble man. He never recognized the impact he had made on his community; nor was he aware of how much he was loved or how much he would be missed. We would give anything to have him back, if even for just a moment to convey to him the monumental impact he so freely bestowed on so many. Jeremiah was undoubtedly an asset to his family, to his friends, and to his community. He will never be forgotten, and will forever and most honorably be remembered not for who he was when he died, but for whom he was when he lived.

The fact that we share Jeremiah’s life is to help raise awareness of the seriousness of repeated hard hits and concussions. Thank you to all research team members of Boston University. Your professionalism, compassion, understanding, sensitivity, and organization are most deeply appreciated.

Philippians 4:8

Finally, brothers and sisters, whatever is true, whatever is noble, whatever is right,

whatever is pure, whatever is lovely, whatever is admirable,

if anything is excellent or praiseworthy, think about such things.