Holly Matson

Luke Matson

Ollie Matson

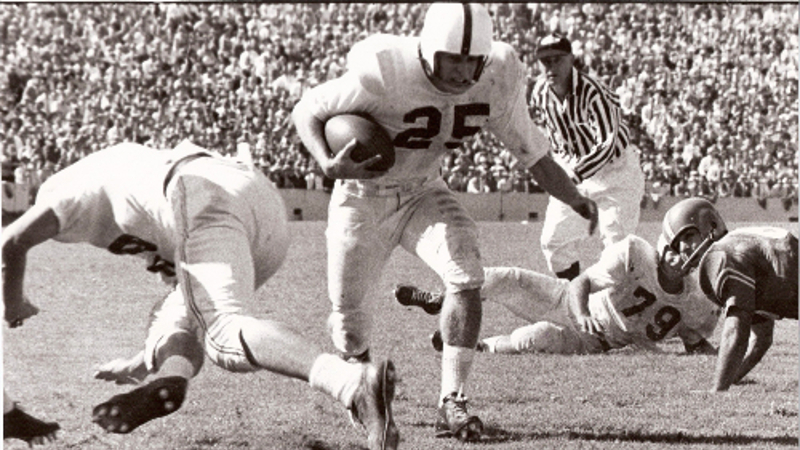

Most athletes can only dream of reaching the pinnacle in just one sport, let alone two. Ollie Matson was not like most athletes, however. Not only is he a member of both the College Football Hall of Fame and the Pro Football Hall of Fame, he also won two Olympic medals with the U.S. Olympic track and field team in 1952.

Matson started playing football as a freshman at George Washington High School in San Francisco before joining the University of San Francisco Dons as a star two-way player. He was a 1951 Heisman Trophy finalist following his senior season, when he led the country in both rushing yards and touchdowns. While Matson finished ninth in Heisman voting, his performance led the Chicago Cardinals to select him third overall in the 1952 NFL Draft. Matson went on to play 14 seasons for the Cardinals, Rams, Lions, and Eagles. Throughout his career, Matson was a six-time Pro Bowler, and his 12,799 career all-purpose yards at the time of his retirement ranked second all-time only to Jim Brown. Matson is a member of the NFL 1950s All-Decade Team and was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1972 and the College Football Hall of Fame in 1976.

Upon retiring from football, Matson joined the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum as its director of special events, where he remained until retirement in 1989. Outside of work, Matson dedicated his life to others. He was a passionate volunteer who spent much of his free time mentoring children, especially those in juvenile hall and corrections. Matson also served as a football coach for nearby Los Angeles High School.

But family always came first and foremost.

“My grandfather was a gentle giant, soft-spoken and disciplined,” said Matson’s granddaughter Lara Parker. “He made sure to spend time with all of his children and grandchildren, even though they were scattered throughout the country.”

In addition to being with family, Matson followed a strict daily routine of his favorite activities, including cooking and gardening. He stayed active by walking every day from his home to L.A. High School and back. He also loved watching horse racing but had to stop when his memory began to worsen, as he would forget how to return home from the track.

Once Lara graduated from college, she moved back to Los Angeles to help take care of her grandfather, who had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. As the only person around him full-time, Lara was able to see his changes firsthand. Though Matson never talked about the injuries he sustained while playing football, his wife and twin sister often commented on the amount of hits he took. There were occasions he stayed in bed for days with a headache, only to take the field again as if nothing happened. One particular college game comes to mind: a 1951 matchup against the University of Tulsa. Matson was specifically targeted and hit by the other team for being a Black player.

The always determined Matson slowly started acting in unrecognizable ways, becoming almost childlike at times. Once he reached his 70s, he could no longer drive and did not have the capacity to stay active. There were moments he would forget how to do simple tasks like taking a shower. Matson would get down to play with his grandchildren, but not have the strength to get back up. And though he remained stubborn, he fortunately was never aggressive or physical around people. While Matson’s family originally attributed his decline to Alzheimer’s and old age, they sensed something else more serious might be in play, as news about former football players diagnosed with CTE became widespread.

After Matson’s death in February 2011 at the age of 80, his family made the decision to donate his brain to the UNITE Brain Bank. Researchers diagnosed him with stage 4 (of 4) CTE and noted it was one of the most severe cases they had seen at that time. In fact, they were shocked he was able to survive so long in his condition.

“We discussed the donation before his death, suspecting he was in the end stage of CTE,” said Lara. “The hope was to help future families from suffering like we did.”

Though the Matson family wasn’t surprised by the diagnosis, they were startled by the severity. Because Matson mostly kept everything to himself, they didn’t know how much he was struggling.

“He must have known something was wrong but couldn’t express it,” said Lara. “Was he depressed? Sad? Frustrated? It’s painful to know the strongest person you know was suffering internally and we couldn’t help.”

Lara and the rest of the Matson family want other families who may be in a similar situation to learn from their experience. They are strong supporters of CLF’s Stop Hitting Kids in the Head campaign, which aims to convince sports to eliminate repetitive head impacts under the age of 14 to prevent future cases of CTE. She urges other parents to reevaluate their young children’s involvement in contact sports and the potential risks of pursuing this path.

“Ultimately, we want Ollie’s donation to help further this crucial research so we can truly understand the impact of concussions and related traumatic brain injuries,” said Lara. “We also want others to know no matter how bad something may seem, you’re not alone, and there is a strong network of other families like ours who understand.”

Robert D. Mattix

Ed Mayer

Frederick R. McClelland

R. Wayne McDaniel

Long before he succumbed to stage 4 CTE, Wayne McDaniel was an extremely talented athlete, lettering each year of high school in baseball, basketball, and football. It was his football prowess that earned him a four-year scholarship to the University of Florida. Upon graduation from UF, he coached football and baseball before joining the UF Office of Development, serving as the alumni association’s executive director for 27 years. He, like so many victims of CTE, was a highly motivated and talented individual. There was nothing he couldn’t do. But that would change.

I am Melissa, Wayne’s wife. We were together over 30 years throughout the slow, destructive path of his CTE. I write this with the hope that other spouses, sons, and daughters who are currently living with the collateral damage of this disease might at least have a sense of what may lie ahead.

When we first met, Wayne was at the top of his game both professionally and personally. His extraordinary good looks (what a face!) and athleticism were captivating, but what I really could not live without were his sharp wit and talent for making absolutely everything fun. Only now, as I look back on our first 10 years together, am I able to recognize the first harbingers of what was to come. Two of those signs still burn in my brain. The first was a noticeable decrease in financial aptitude. It concerned me so much that I chose to keep my name and finances separate when we married, which turned out to be a godsend. I strongly encourage anyone noticing even a hint of change in financial habits to act immediately to protect what you have.

The second sign something was off was Wayne’s sudden desire to withdraw from social interactions with longtime buddies. He didn’t seem to have the energy to spend a full weekend with friends at their lake house or attend a reunion with his old teammates. Around this time, I became both protective and defensive. To save face for Wayne, I publicly blamed myself as the reason for his refusal. I didn’t realize what I was doing to protect my husband caused others to perceive me as a selfish snob and a recluse. This added to us becoming increasingly isolated at a time we needed companionship most.

The second decade of Wayne’s life with CTE brought edginess, distrust, and impatience. I remember stressing about the “why” of it all. This man — who had been so loving and warmhearted — was now quick to anger and to criticize the smallest things. He could keep it together with others outside, but inside our home, a new, sometimes frightening persona might appear. Was this male menopause? Grumpy old men’s disease? Too much stress at work? Too much self-medication with booze? CTE was still unknown to me; I needed answers but was too protective of my husband’s privacy to go public with my concerns.

Fortunately, around this time we accepted an invitation to visit the North Carolina mountains. This completely different environment with new people and experiences improved Wayne’s demeanor so much, it was like a welcome prescription from the doctor. Our impulsive decision to invest in mountain property improved our quality of life, and “quality of life” became my mantra, a goal which would help me focus in the years to come.

As I witnessed Wayne’s escape into a simpler mindset, I realized he was sicker than anyone knew. Shock, anger, and bargaining, the early parts of the five stages of grief, had already been happening for some time. I was fearful and depressed, but still ready to fight. Fortunately, the backdrop of my new mountain home in Asheville, N.C., was a mecca for alternative naturopathic and herbal medicine. In the years that followed, I devoured hundreds of hours of continuing education classes, sitting beside doctors and nurses with a medical mindset I didn’t know existed. It was in those courses I learned about foods, herbs, and natural compounds which might at least relieve some of my husband’s infirmities.

By the third decade of Wayne’s life with CTE, I finally became aware of the disease after watching the movie Concussion and the publicity surrounding Aaron Hernandez’s murder conviction and suicide. Almost certain my husband had it, I approached brain and memory doctors in our primary residence of Gainesville, Fla. However, Wayne’s denial that anything was wrong cast me in the light of a hypervigilant wife, and his refusal to have an MRI or submit to a psych test stopped further analysis.

We found the amino acid theanine (think green tea or matcha) helped calm Wayne to the point he could actually relax. Tyrosine is another amino acid often used by Alzheimer’s patients to achieve similar mood-lifting results. The Ayurvedic herb bacopa was also calming, and when Wayne took it regularly, his focus improved. These natural alternatives helped greatly as we maneuvered the last five years of my husband’s life. Not only did they calm him, but they also made him not hostile.

Toward the end of Wayne’s life, however, his primary doctor made me stop giving him anything natural. I had fought hard not to do that, but by that point, I was ready to give up. Soon after stopping the natural alternatives, my husband became violent, biting, kicking, and hitting anyone who came near him. By then, he was in the hospital, so I explained what was happening to the doctor on call. She researched tyrosine, the supplement I thought he was missing most, and she approved it. Shortly after I gave it to Wayne, he started to calm down. I’m not saying this works for everyone, but it did prove the viability of tyrosine to me and that particular doctor. Unfortunately, Wayne’s stage 4 CTE won the fight, and his organs failed him. He died on May 3, 2022. His death certificate lists five organ-related causes and the additional diagnosis of stage 4 CTE and Alzheimer’s disease from the UNITE Brain Bank.

Now, one year later, I dwell on the reality that there may be thousands, even tens of thousands of middle-aged men who have tau plaque growing in their brains. This is happening to them because they were dynamic, motivated athletes who did not know they were sacrificing their brains for sports. In doing what it took to earn scholarships or for the sheer joy of competing and gaining respect, they may have sacrificed their capacity to love, to learn new things, to manage their finances, even to manage their lives.

These men strive to seem as functional as possible to the outside world. But inside, they are sick. In their own homes, their spouses and children are also hurt by collateral damage from this disease. Something must be done to recognize there is a plague of CTE out there, and many victims and their loved ones may not even be aware of it.

I wish the naturopathic community would be more vocal about herbs and natural, nonpharmaceutical compounds that might help at least some of those suffering from CTE and their loved ones get through the bad days and long years. Raising awareness of the suffering from CTE is also a worthy cause. We all should do whatever we can to help the Concussion Legacy Foundation make that happen.

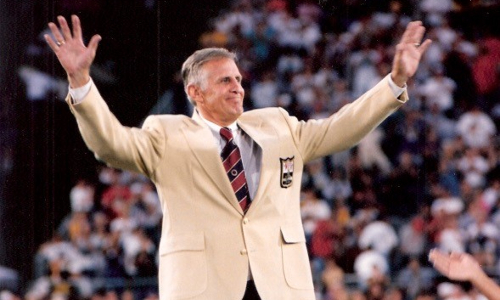

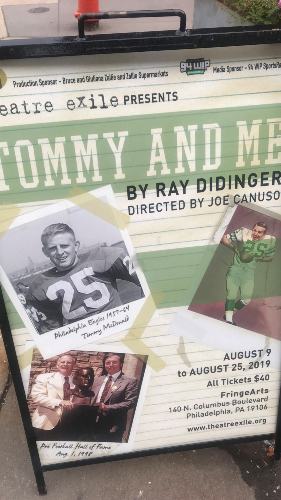

Tommy McDonald

Tommy McDonald told anyone he could to follow their dreams – that anything was possible. He said it because he lived it.

McDonald was born in Roy, New Mexico in 1934. As a kid, McDonald was small but extremely quick. He would give his dad cash he won in footraces. Knowing his son had considerable talent but very little chance of getting noticed by college coaches in Roy, McDonald’s father moved the family to the bigger city of Albuquerque when McDonald late in his sophomore year of high school.

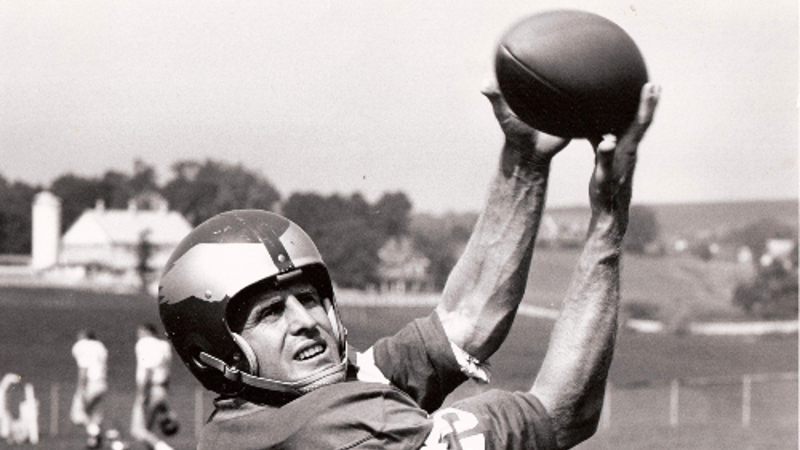

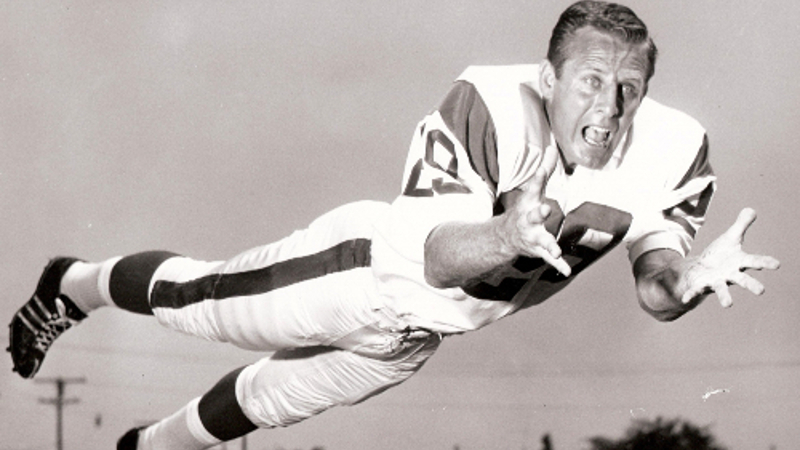

In an era without the assistance of high-tech receiver gloves, many pundits stated McDonald had the best hands in the NFL. McDonald appeared on the cover of Sports Illustrated in October 1962 with the caption “Football’s Best Hands.” But the statement applied to McDonald’s ability to catch footballs, not to the literal shape of his hands. In Albuquerque, McDonald’s father held Tommy back a grade to allow him to grow. In exchange for delaying his schooling, McDonald’s father supped up a motorbike for Tommy to ride around town with. One day, a car cut McDonald off while he was riding, leading his bike’s clutch to snap and completely sever a third of McDonald’s left thumb off.

Despite that, McDonald dominated New Mexico athletics. He won five gold medals in the state track meet, set his city scoring record for basketball, and set the state scoring record for football as a running back. His exploits earned him a scholarship to play running back for Oklahoma University.

One could argue his career at Oklahoma was one of the best in college football history. In McDonald’s three seasons of varsity play in Norman, the Sooners never lost a game, winning two National Championships over the span. In 1956, McDonald finished third in Heisman voting and won the Maxwell Award, given to the best all-around player in the country.

In 1957, the Philadelphia Eagles drafted McDonald 31st overall in the NFL Draft. McDonald’s exuberance, grit, and production instantly connected him with the city of Philadelphia. When McDonald scored the first touchdown in the 1960 NFL Championship at a snowy Franklin Field, Eagles fans mobbed him in the corner of the endzone.

The Eagles beat the Green Bay Packers 17-13 that day. After the game, legendary Packers coach Vince Lombardi said, “If I had 11 Tommy McDonalds, I’d win a championship every year.”

One of McDonald’s trademarks was springing up quickly from the turf after big hits. Teammate Chuck Bednarik once accused McDonald of getting up too quickly after such hits. But at 5’9,” 175 pounds, McDonald used every tactic he could to convince opponents they could not get the best of him.

McDonald’s son Chris estimates his dad bounced up after a big hit and went back to the huddle following a concussion dozens of times.

There were some hits McDonald could not downplay. He told a story of getting knocked out cold in San Francisco and waking nearly 10 hours later in Philadelphia. Another time, a Dick Butkus hit left McDonald unconscious for more than a minute. He missed only two plays before returning to the game.

“If you looked like you were OK and your cobwebs were clearing, they sent you back in,” said Chris.

McDonald finished a decorated NFL career in 1968 as a member of the Cleveland Browns. He missed only three games in 12 seasons. At the time, a decade in the NFL still meant you would need to find a day job after retiring. His requited love for the people of Philadelphia led him to make the city of brotherly love his permanent home.

He lived outside of Philadelphia and ran an oil painting and plaque business. He and his wife Patricia had four children together. His boundless energy could have powered the stadium’s lights, leading Eagles’ brass to invite McDonald to countless games, team events, golf tournaments, and autograph signings. But after days full of smiling and posing for pictures, he loved nothing more than loading up the family car and going out to Chinese food in Philadelphia’s center city.

“He never bragged about his stats,” said McDonald’s daughter Tish. “He was just dad.”

Just dad became just grandpa. He loved attending his five grandchildren’s games, where he was famous for providing tips to the young players and infamous for pulling pranks on his fellow spectators.

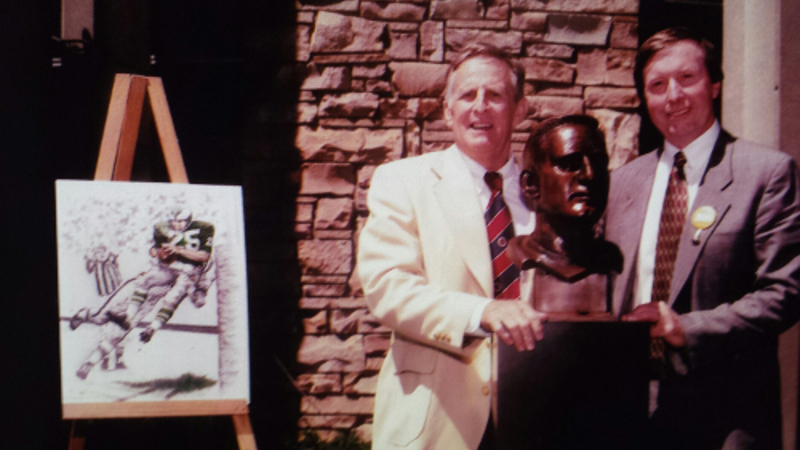

In the 1950s, a young Eagles superfan named Ray Didinger frequented Eagles’ training camp in Hershey, Pennsylvania with his family each summer. He delighted in getting to hold Tommy McDonald’s helmet and interact with his hero as the team walked on to the practice field. 40 years later, Didinger, then a decorated Philadelphia sportswriter, led a campaign to get McDonald inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame. In 1998, McDonald got a call he wondered if he would ever receive. He was to be enshrined in the Hall of Fame that summer.

After Didinger introduced McDonald to the audience in Canton, Chris and many of the family members expected McDonald to share his story of overcoming a small stature and a small town to inspire kids across the country to never give up on their dreams. McDonald went in a different direction. He cracked jokes, tossed his 35-pound Hall of Fame bust up in the air, played the Bee Gees’ “Stayin’ Alive” from a boombox, and chest-bumped all his fellow inductees.

Some members of McDonald’s family were surprised by Tommy’s speech. But for the same reasons he flung himself up from big hits as a player, McDonald explained to his family that his on-stage antics were a way to hide his pain.

By then, McDonald became emotional very easily. His father had passed away four years earlier and his mother was too ill to attend the ceremony. Having been extremely close with both parents, McDonald guessed he would unravel if he started talking about them in a conventional speech. He chose to keep it light instead.

McDonald’s emotionality was one of the first signs of change in his later years. His memory came next.

McDonald had driven the same route from his home in King of Prussia, Pennsylvania to Lincoln Financial Field in Philadelphia dozens of times a year for the past six decades.

But on his way back from a Philadelphia Eagles event in 2008, Tommy McDonald called his wife.

“The car could have been on autopilot, he’s been there for 50 plus years,” said Chris. “But he was totally lost.”

Whenever his memory failed him, McDonald, who never cursed, lamented about “these dang concussions.”

For most of his senior years, McDonald stayed active by playing tennis and racquetball. But McDonald’s cognitive issues escalated when he became more sedentary.

After his induction, McDonald eagerly returned to the Hall of Fame every summer. He loved the honor of being in football’s elite fraternity and enjoyed celebrating each year’s new class of honorees. But McDonald’s memory regressed to the point where returning to Canton provided too many opportunities where he could fail to remember someone’s name. He stopped going entirely.

“He didn’t trust his mind,” said Chris.

Outside of the bursts of emotion, the memory loss and the associated frustration, the McDonald family says Tommy maintained a positive spirit throughout his life. Chris and Tish remember him often saying, “I’m above the grass,” through a giant grin.

In 2015, Didinger produced a play, titled Tommy and Me. The play celebrated the odds McDonald overcame throughout his life and showed how McDonald made an indelible impact on Didinger’s life. The entire McDonald family attended the first reading of Tommy and Me. McDonald was delighted throughout the reading.

“That was my way of repaying him a little bit,” said Didinger in 2016.

As McDonald aged and his cognitive problems first emerged, Tish, Chris, and their siblings Sherry and Tom assisted with his care. Chris read news of other former NFL players suffering from Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE). The family heard from other football families about former players struggling in similar and different ways as Tommy. It led Chris to decide to donate his father’s brain to research after he died.

“If he could help another player out and make the game better and safer for today’s player,” said Chris. “Then he’s all for it.”

In the mid-2010’s, McDonald’s wife Patricia suddenly contracted Lewy bodies with dementia. She died on January 1, 2018. On the way back from her funeral, Tish remembers her father staring back at him, eyes agape. It was only then that he realized his wife of 55 years was gone.

“That was how bad it got,” said Chris. “He was really out of it.”

Eight months later, on September 24, 2018, Tommy McDonald passed away at age 84.

Chris followed through on brain donation and McDonald’s brain was studied first at the University of Pennsylvania then at the UNITE Brain Bank in Boston.

Tommy McDonald holds several amazing distinctions. He is the shortest player in the Pro Football Hall of Fame. He is one of the last players to play without a facemask. His Oklahoma Sooners’ winning streak of 31 games seems immortal. He holds the Eagles’ record for receiving yards in a game. Now, he is one of the many former NFL players to be diagnosed with CTE.

Dr. McKee, Director of the Brain Bank, diagnosed McDonald with Stage 4 (of 4) of the degenerative brain disease. She said McDonald’s brain pathology explained the massive memory loss he experienced in the last decade of life.

“What I found was classic for long-standing CTE,” Dr. McKee said in a 2021 interview with the Philadelphia Inquirer. “It had all the characteristic lesions around vessels involving a considerable extent of the brain.

For the McDonald family, the diagnosis confirmed what they had already come to realize: more than 20 seasons of football filled with dozens of concussions had done severe damage to Tommy’s brain. Just as proud as McDonald was each year to return to Canton, they are proud to help Tommy give back to the game he loved through CTE research.

Chris and Tish believe their dad’s story of overcoming his size and circumstances, the story he didn’t tell at his Hall of Fame induction, is one anyone can take to heart.

“His number one thing would be to not let anybody tell you, ‘You can’t do it,’” said Chris of his father. “If you have a goal in life, stay determined and persevere.”

For other children of CTE, their message is to relish every moment you get with your parent.

“Enjoy every single day that he’s here, even if it’s a small percentage of him,” said Tish. “Because when they’re gone, they’re gone. You never get to hug them again, give them a simple ‘hello’, or tell them you love them.”

Keli McGregor

Former Rockies president Keli McGregor’s legacy lives on

DENVER (AP) — It’s been a year since Rockies President Keli McGregor, a 6-foot-7 fitness fanatic and former NFL player who was the picture of health, died on a business trip in Utah at age 48, sending shock waves through the club and the Colorado sports and business community.

His legacy lives on in many ways big and small, both in Colorado and in Arizona, where the planning and construction of the Rockies’ new spring training complex in Scottsdale consumed much of his final years.

Wednesday marks the one-year anniversary of McGregor’s death, and reminders of him are everywhere.

The Rockies have painted his initials “KSM” over purple pinstripes inside a giant baseball in right center field. Some players still have his picture on the leaflets handed out at his memorial taped to their lockers.

“I think you see it in the organization that he helped build,” catcher Chris Iannetta (FSY) said. “I think you can see it in the spring training complex that he helped build and I think you can see it off the field in the relationships that he had.”

Manager Jim Tracy said: “I think the first place and the best place to start would be take a walk through our spring training complex. In addition to the Keli S. McGregor fitness area, his fingerprints are all over our spring training complex.”

Iannetta said Colorado’s 12-4 start was directly attributable to the team’s move to spiffy new digs in the Phoenix area. No longer do the Rockies have to make two-hour bus trips between Phoenix and Tucson, where they were often forced to face minor leaguers because other teams were reluctant to bring their front-line players and starting pitchers to Hi Corbett Field.

Iannetta said the players were refreshed when the season started and had already hit stride several weeks earlier instead of having to do so in April, when the Rockies have traditionally gotten off to slow starts.

“I think it’s the continuity of the lineup, the continuity of the guys playing on consecutive days, not having to travel, and facing better pitching,” Iannetta said. “Teams were reluctant to bring their No. 1s down to Tucson, and when we played the Diamondbacks, they never showed us their starting staff anyway. So, I think we’ve benefited from that.”

Regardless of the wins or losses, “he would be proud of us because we go out there every single night and play hard and that’s all he ever asked for,” slugger Troy Tulowitzki (FSY) said.

“And I think not only on the baseball field but I think being good role models off the field is really what he appreciated and standing for the right things,” Tulowitzki said. “And in this clubhouse we have a bunch of really good guys on and off the field and that’s what he’d be most proud of.”

On Wednesday, the Rockies will dedicate a baseball field in his honor in nearby Lakewood, where he grew up.

McGregor, a former NFL tight end, had passed a physical just before spring training last year. He’d later caught a cold, but nothing that would have kept him from accompanying other team officials on a business trip to Salt Lake City.

When he didn’t meet them in the lobby one morning for their flight home, police were called and found his body in his hotel room. It was later determined the father of four died from a viral heart infection.

McGregor’s loss shook the sports communities across Colorado, where he was a multi-sport athlete at Lakewood High School, starred as a tight end at Colorado State and was drafted by the Denver Broncos. He also played for the Colts and Seahawks before going into coaching and then embarking on a career in sports administration, joining the Rockies in 1993.

Commissioner Bud Selig called McGregor “one of our game’s rising young stars.”

His widow, Lori McGregor, told the Denver Post during spring training that tests after her husband’s death revealed he had a degenerative brain disease called chronic traumatic encephalopathy, which causes memory impairment, emotional instability, erratic behavior and depression and eventually develops into full-blown dementia.

She said her husband suffered a couple of concussions in college and was transfixed one day when he saw an ESPN report on former NFL players suffering from debilitating depression. Although he displayed no symptoms, he wanted his brain and spinal cord donated to the Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy based out of Boston University, she said.

CTE can develop when an athlete is exposed to hits that result in concussions or even as a result of repetitive nonconcussive contact, according to the center.

A cross-section of his brain was tested and came back positive for CTE, Lori McGregor said, telling the Post: “That has truly been the answer to my prayers about this, because I understand now that’s why Keli went, that’s why God took him. Because CTE is ugly and there’s no way to treat it. I really, honestly know that’s why (the heart virus) happened.

“He let a great man die a great man.”