Eugene Merlino

Gene and Kelly Merlino first met in New York City. Gene was charming, generous, good-looking, ambitious, and humorous, all of which initially attracted Kelly to him. The rest, as they say, was history.

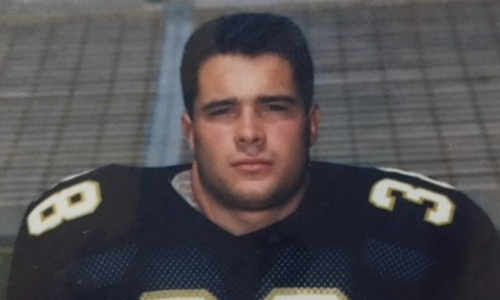

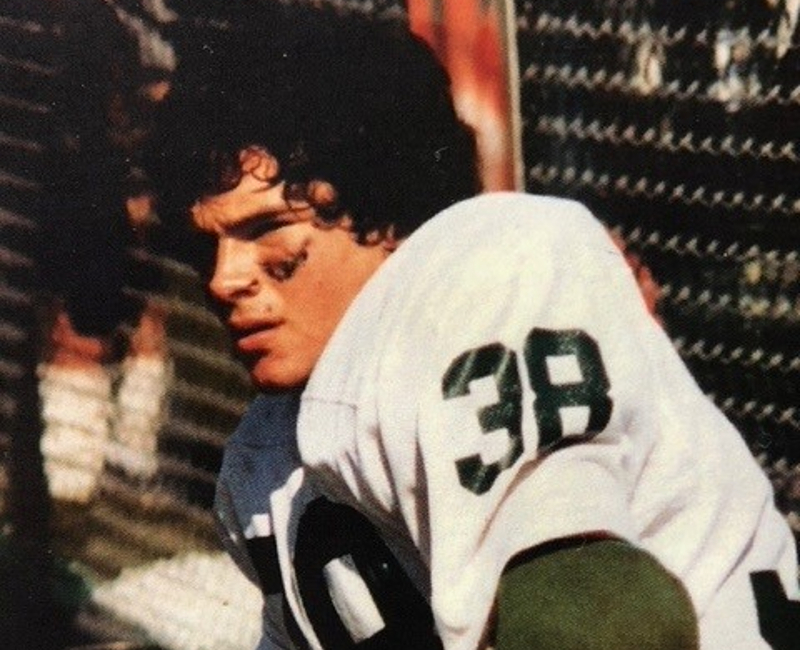

As they grew closer, Kelly learned more about Gene’s beginnings: he was full of life and loved all kinds of sports and being active. On land, he could be found playing football, wrestling, skiing, or riding his dirt bikes and motorcycles. In the water, he enjoyed boating, scuba diving, and water skiing. But his first love was always football. He loved the comradery, being part of a team, and the values it instilled in him. He played the sport starting in third grade, throughout high school, and earned a spot on the Army football team at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point.

The Merlinos dated for a few years before getting married in 1998. They settled down in Mendham, NJ and had three sons: Max, Louis, and Ryder. To Gene, nothing was more important than family. Kelly and the boys were his entire world. They spent the summers up at their lake house in the Adirondacks. They always loved having a house full of family and friends. Gene loved entertaining on their boat and teaching kids to water ski and go tubing. Though everything seemed wonderful in the beginning, Kelly sometimes saw flashes of a different Gene.

Gene had been only a few years removed from football by the time the couple met but was already feeling the aftereffects of the numerous concussions he suffered while on the field.

First were the constant migraines. There was frequent times Gene could barely tolerate any light or sound, so at times he had to stay by himself in a basement, in complete darkness, to find relief. Then there were the nosebleeds; Kelly remembers certain moments when he was profusely just gushing blood everywhere.

Still, on the good days, Gene was an amazing husband, father, and friend. He took great pride in providing a stable life for his wife and kids. He coached Max’s football team and made it a priority to attend his children’s games. He loved being a mentor for the players he coached and teaching them about the philosophy of a team sport, which he fully believed could be applied to many aspects of daily life. But eventually, the number of good days started to disappear. Gene experienced periods of brain fog where he could not think straight, organize his thoughts, or recall memories, even if they had occurred recently.

Kelly kept a journal to help herself cope with the changes in Gene. The journals in turn helped to track Gene’s symptoms and the changes in his personality. She didn’t realize until reflecting on the entries how severe the personality and behavioral changes were and how quickly they were happening. Looking back on her entries now, she says her days mostly revolved around trying to help her husband and keep her family safe while her life became entirely consumed by chaos.

“It was terrifying and difficult to process for the entire family,” said Kelly. “We struggled with the question, ‘How does someone you love change before your eyes with no explanation?’”

As Gene entered his 40s, his personality shifted drastically. Each new day brought a waiting game to see how he would act. The majority of the time, Gene’s mood dominated the energy in the home which inevitably trickled down to Kelly and the children. He was unpredictable and could be fine one moment, but moody or frightening the next. Impulsiveness and rage were part of the new normal. The once social Gene became withdrawn, self-destructive, paranoid, overly negative, and not present. He struggled to follow conversations and would get easily frustrated. Work became more and more difficult due to the deteriorating of his executive functioning skills. He struggled with organizing, following directions, and would lose large gaps of time. Sleep became elusive and he’d stay up all night with his mind racing. He could snap at anyone on a whim, from family to strangers.

“Towards the end of his life it was like he was a shell of the man he used to be,” said Kelly. “He would constantly tell us that he was a burden to us all and we would be better off without him.”

In 2013, Gene was featured on a GQ docuseries called Casualties of the Gridiron, which looked at the impact of concussions on football players. Cameras documented his difficulties, Kelly’s experience as a caregiver, and their journey finding help and answers for Gene.

“I have this, I call it sponge head or fog head. It just doesn’t go away,” described Gene of his struggles in one clip. “I wake up every morning and I open my eyes and there it is again. It starts to become so overwhelming.”

Gene continued to battle symptoms in his early-mid 40s before passing away on July 9, 2021 at the age of 55.

Back in 2012, Gene had gone by himself to Boston without telling anyone, wanting to donate his brain to research. He knew he had all the symptoms of CTE and suspected he might have the disease. When Gene returned home, he gave Kelly the official paperwork and let her know he wanted to donate his brain when he passed. After his passing, she fulfilled his wish and his brain was studied at the UNITE Brain Bank, where researchers diagnosed Gene with stage 2 (of 4) CTE.

Upon hearing the results, Kelly, her sons, and family felt relief knowing their suspicions were confirmed. They now had an explanation for why he morphed into a completely different person.

Kelly is sharing her husband’s story to help raise awareness around CTE. For too long, Kelly and her sons felt as if they needed to keep Gene’s behavioral changes a secret which needed to be kept to protect Gene. There was very little help for Gene, for her, or their children. She wants other families to know they are not alone. There are resources available, such as the CLF HelpLine, which can provide personalized support and guidance to anyone struggling from a brain injury.

Her biggest piece of advice to other families and caregivers?

“When they tell you what they’re feeling and experiencing, please believe them, and support them as best as you are able to,” said Kelly.

Julian Merlino

Julian Alexander Merlino loved dancing hip hop from the time that he was 5 years old. As a young boy, Julian was diagnosed with depression and anxiety, which made him feel shy and insecure. Whenever he danced hip hop on stage, his fears would disappear. Little did he know, his years of dancing hip hop would be a great transition into playing football. Julian began to play football in the 7th grade.

Unfortunately, during the first game, he took a helmet-to-helmet hit and was concussed. He was out for several games and missed numerous days of school.

In 8th grade, Julian suffered another concussion. This one kept him out for two weeks and the remainder of the season.

He played for almost two more seasons as a running back — #26. Julian was a beast on the field. During his freshman and sophomore years playing football, Julian never complained of concussions, probably because he knew that if he was concussed one more time he’d be out of football for good. However, Julian’s friends would notice that he was visibly shaken and unwell after games.

During his sophomore season, Julian began to miss football practices and school. He began losing interest in his greatest passion. His behavior became aggressive and he was irritable. Two months later, on December 30, 2017, Julian took his life at age 15.

Julian loved spending time with his family, girlfriend, and friends. He enjoyed discovering the newest hip hop music. When he wasn’t in his hometown during the school year and playing football, he enjoyed endless summer days boating and surfing on the lake with friends. He was a jokester and prankster. Julian is missed terribly by his family and friends.

In search of some answers and to help others, Julian’s family donated his brain to the UNITE Brain Bank. Julian was the youngest brain donor in the history of the Brain Bank.

A message of hope from Julian’s parents and sister:

We want anyone reading this who may be feeling chronic debilitating pain, desperate, lonely, or depressed to know that things will get better! Don’t let your struggles define you! Reach out to a friend, family member or coworker. You are loved! With help and support you will feel well again. You are not alone! Don’t give up hope!

Julian’s mom, Elsa, is a mental illness and suicide support advocate for families who have lost a child or family member to suicide. Elsa personally writes letters of hope to others who have suffered the unimaginable. It’s a simple gesture to let these moms know they are not alone. When suffering from suicide grief, it means the world to these moms and family members that they are not alone.

Suicide is preventable and help is available. If you are concerned that someone in your life may be suicidal, the five #BeThe1To steps are simple actions anyone can take to help someone in crisis. If you are struggling to cope and would like some emotional support, call the 988 Lifeline at 988 to connect with a trained counselor. It’s free, confidential, and available to everyone in the United States. You do not have to be suicidal to call. If you’re not comfortable talking on the phone, consider using the Lifeline Crisis Chat at www.crisischat.org.

If you or someone you know is struggling with lingering concussion symptoms, ask for help through the CLF HelpLine. We provide personalized help to those struggling with the outcomes of brain injury. Submit your request today and a dedicated member of the Concussion Legacy Foundation team will be happy to assist you.

The Merlino family would also like to bring awareness to the Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance (DBSA). The vision of the DBSA is for wellness for people living with mood disorders (depression and bipolar disorder). Their mission is to provide hope, help, support, and education to improve the lives of people who have mood disorders.

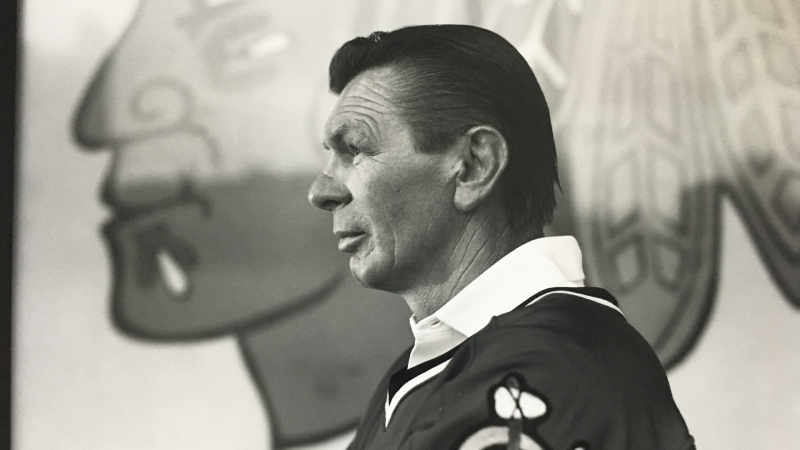

Stan Mikita

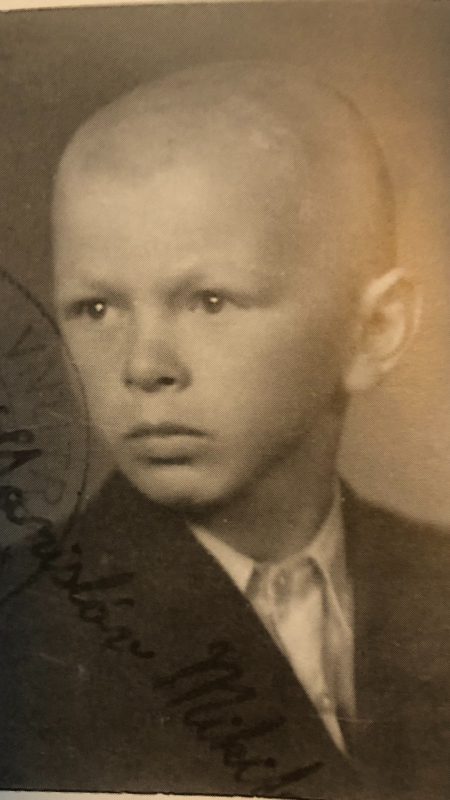

It is important to understand the manner in which our father lived his life: his compassion for others, his ability to meet a stranger and make a friend, and his devotion to family and friends defined him. Our father was born in Sokolce in 1940, then a part of communist Czechoslovakia. At the age of 8, his aunt and uncle visited to ask if they could adopt Stan and raise him in Canada. Stan’s mother, Amelia, and father, George, refused. Then came the miscommunication that would change the course of Stan’s life: the hungry 8-year-old came in to ask for a snack. When Stan was sent back to bed without his snack, he cried. His parents thought he was upset because he wanted to live in Canada, so they changed their minds and let him go. That small moment set in motion a series of events that greatly impacted our dad’s life.

When he arrived in Canada, Stan did not speak the language. He looked different than the other kids and he was not with his “real” family. Even though he was 8 years old, he was placed in a Kindergarten classroom due to his lack of English language skills. He was bullied, he was called a DP (displaced person, a great insult), he had no friends, and in his mind, he didn’t have his family.

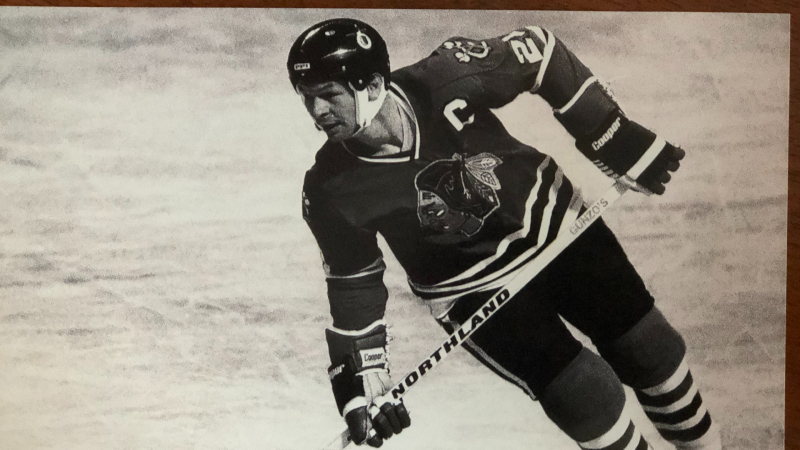

In the midst of that great loneliness, he found the game of hockey, which would go on to become a great joy of his life. While our dad’s professional hockey accomplishments were many, we are most proud of his legacy of giving back and caring for others.

Those early moments upon his arrival in Canada made a lasting and profound mark on our dad. He learned what it was like to be alone in a world full of people, and how to reach out to others who felt that way. Our dad was a husband, father, and grandfather who fiercely loved his family above all else. A friend who would always lend a hand and never missed an opportunity to pull a prank. A kid from Czechoslovakia who never forgot the sacrifices his parents made, his feelings of being different and left out or his humble beginnings. A selfless Chicagoan who felt a duty to give back. A human who saw other people with differences as simply that – people.

As a father, he taught us by example about acceptance, compassion and patience, often reminding us that it doesn’t cost anything to be nice to people. He stressed that everyone is equally worthy of respect and kindness; that people are more alike than they are different. Our dad would ask us if we wanted to go to a track meet or a visit a hospital with him. He never qualified these outings as doing charity work or made note that some of the participants would be mentally, physically or medically challenged. We were just going to cheer some people on. We accompanied him to be “huggers” at the Special Olympics when he helped start the program in Chicago. When our dad and Uncle Irv founded AHIHA (American Hearing Impaired Hockey Association) in 1973, we were all involved from the beginning, helping any way we could. AHIHA is still going strong, fielding the US Deaf Olympic Team. The next generation of Mikitas, the grandchildren, continue to support the program by volunteering on and off the ice. Many of our good friends are AHIHA families. On Thanksgiving we would go to Larabida Children’s Hospital to play and have lunch with the kids and their families.

Several years ago, our father began declining mentally. Almost overnight, our mother’s partner of 52 years was mentally gone but physically still here. Our loving father and doting grandpa was suddenly confused and different from the person we knew.

This new journey was a change for all of us. As a family we decided that it was important to share news of his dementia. Our public statement was met with sorrow, understanding, compassion, love and support for both Stan and our family. We knew we were not alone in this journey, ours was just going to be a little more public than most because of Stan’s name and notoriety.

This is not a path any family foresees for a loved one, but it is, unfortunately, one that unites many of us. One amazing revelation was that once people knew that Stan was suffering with dementia, almost everyone who reached out to us had a family member or loved one fighting the same battle.

Because of the way our dad lived his life, during the end of his life, we were supported and loved by so many of the people he had touched. Friends, former teammates and rivals, kids he visited at schools and hospitals, old neighbors and strangers all reached out to offer comfort and share memories.

In keeping with the way he lived his life as a giver, it was our father’s idea to donate his brain to the UNITE Brain Bank upon his death. He made his wishes abundantly clear, and as he said in his book, “This is a serious issue, and I am willing to be part of a test group. While I’m alive, I will gladly cooperate with the investigation of post-concussion syndrome. It’s the least I can do.” He visited Boston in 2013 to undergo baseline testing with Dr. Stern. He knew this was not diagnostic testing and he would not be receiving any medical treatment to help his memory loss, but that this information would be able to help others in the future. He told our sister Meg after the testing, “I told them they could have my brain, but not yet, I’m still using it.”

Our dad ended his book, Forever a Blackhawk with this quote, “By now, I thought for sure that I would be forgotten. Instead, I am still being remembered. How lucky can a guy be?” We were lucky to have him as a dad and friend, and we are honored to continue Stan’s wish to give back.

-The Mikita Family

Jill Mikita – wife

Meg Mikta

Scott Mikita

Jane Mikita Gneiser

Chris Mikita

Bobby Miller

Jackson Miller

Courtney Mills

Nick Miniati

Nick was a vivacious child and a charmer. He was always a balance between rugged and sensitive; shy and intense; carefree and caring.

He grew up surrounded by his family, making memories with his brother, cousins, and friends whether it was playing games in the backyard, golfing, fishing, kayaking, visiting the White Mountains of New Hampshire, Chatham, the Caribbean or trips to Disney World, where he went more times than he could count!

Nick kept the people he liked close and was fiercely loyal to his family and friends. He was always there to lend a helping hand, watch sports, or just hang out.

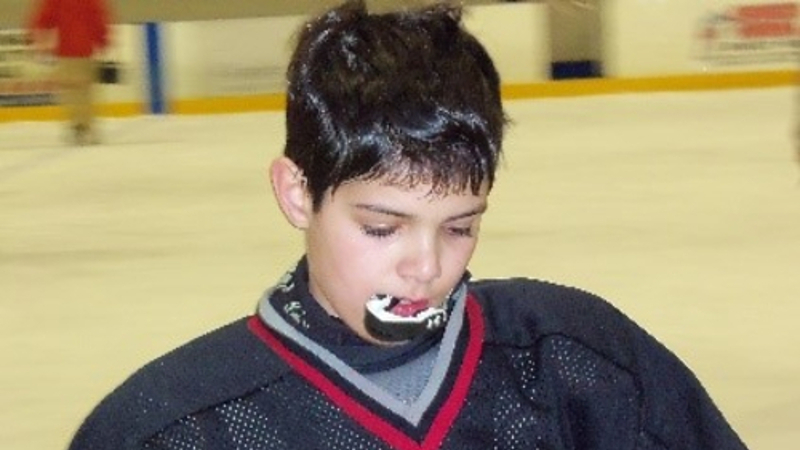

Some of his earliest and closest friendships came from hockey, which was his passion from the first time he put on a pair of skates.

When he looked in the stands, he always saw his mom there and often other family members cheering him on. He could always find his dad watching rink side, near the goalie net because he wanted the best view of Nick when he scored a goal!

Nick carried with him his father’s voice booming: “Skate hard!

Nick played with grit and determination. He was never afraid to go up against larger opponents and battle it out in the corners. In early adolescence, he suffered two significant concussions that we sought treatment for.

But the extent of Nick’s head trauma was not limited to those two diagnosed concussions. Later in life, Nick revealed to his family how he had his “bell rung” more times than he could remember. He never considered these incidents as concussions or told us about them when they happened.

Nick hid the physical and emotional pain he was in from others. His friends never knew what he was going through and, initially, neither did we. But his suffering began to manifest in ways we could pick up on.

We noticed he had immense difficulty sleeping and was plagued by waves of headaches. He didn’t tell us when his head bothered him, but we could tell he was in pain when he had to step away from TV or video games.

His mental health also declined as he entered his early 20’s. He had mood swings. He lost his motivation and his sense of drive. He began to isolate from others and showed signs of depression.

Nick was seeing a family doctor and began seeing a therapist. There was reason for optimism from how the sessions were going. But even after seeking help, we still saw Nick suffer from many of the same problems.

On September 7, 2020, Nick died by suicide at the age of 22.

Upon Nick’s death, we donated his brain to the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank. There, researchers found Nick did not have CTE, but said he could have eventually developed the disease later in life. Researchers also reported Nick had damage to his frontal lobe, and had brain bleeds deep inside his brain. They noted those types of brain bleeds were greater than expected for his age and may be related to his repetitive head impacts.

Our goal in sharing his story is to highlight the connection between brain trauma and suicide. A 2018 study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association found those who were diagnosed with concussion or mild TBI were twice as likely to die by suicide than those who had not been diagnosed with a concussion or mild TBI. A 2019 study from the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston found teenagers with a history of concussions reported having thoughts of suicide and feeling sad or hopeless at higher rates than teenagers without a history of concussions. The more educated players, coaches, and parents can be about the signs and symptoms of concussion, the safer our kids can be. If you notice a change in behavior on or off the ice, speak up!

Something happened in Nick’s brain that we do not fully understand. But with more research like the work being done at the UNITE Brain Bank, we hope to prevent another family from going through the unbearable pain of losing a child.

Suicide is preventable and help is available. If you are concerned that someone in your life may be suicidal, the five #BeThe1To steps are simple actions anyone can take to help someone in crisis. If you are struggling to cope and would like some emotional support, call the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988 to connect with a trained counselor. It’s free, confidential, and available to everyone in the United States. You do not have to be suicidal to call.

Are you or someone you know struggling with lingering concussion symptoms? We support patients and families through the CLF HelpLine, providing personalized help to those struggling with the outcomes of brain injury. Submit your request today and a dedicated member of the Concussion Legacy Foundation team will be happy to assist you. Click here to support the CLF HelpLine.

Shannon Mocca

Jim Mohr

Warning: This story contains mentions of suicide and may be triggering for some readers.

Jim Mohr grew up in Arcadia, California, in a very loving family. He was the youngest son of Ed and Janet Mohr. As a child, Jim spent his summers on Newport Beach, California where he developed his love for surfing and all water sports. Jim had the fondest of memories growing up in his family and considered them some of his best life experiences.

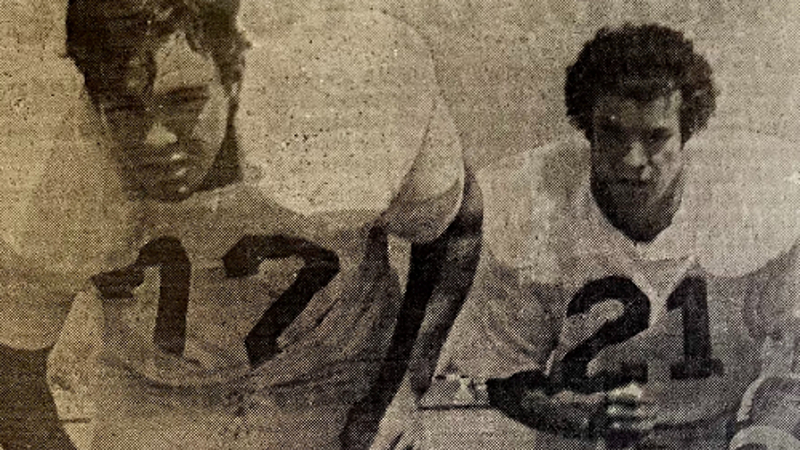

Jim started playing Pop Warner Football at the age of 8. An extremely gifted athlete, he excelled at this sport and quickly became a standout player. Jim LOVED the game of football. He loved the off-season weight training, practices and the camaraderie of his teammates. The combination of his raw talent, work ethic, and natural leadership abilities led him to be an exceptional high school player. Described by his teammates as a “one man wrecking ball who played with reckless abandonment,” Jim started his freshman year on varsity as both the running back and defensive back. He was also the punt receiver and played almost the entire game in every game in his four years at Arcadia High.

His accomplishments included being elected to the first team L.A. Times All-San Gabriel Valley football team in 1977 and 1978. In 1978, he scored 21 touchdowns, rushed for 1,322 yards and averaged 8.3 yards per carry. Jim was named by the L.A Times and the Pasadena Star as Running Back of the Year and All-San Gabriel Valley Defensive Back of the Year along with being selected Most Valuable Player in the Pacific League and named to the All-CIF First Team. Jim was selected to play in the Shrine All Star game, and he was elected co-captain by his teammates with John Elway. He started at both running back and defensive back, helping the North defeat the South 35-15.

Jim went on to play running back, defensive back, and punt returner for Northern Arizona University until he suffered a knee injury requiring ACL reconstruction surgery which ended his football career in his sophomore year. After graduating with a degree in finance, he moved to San Diego to begin his financial advisory career and founded the Mohr Financial Group in 1984. His genuine care for helping people, attention to detail, and unparalleled work ethic led to a very successful career. For almost four decades, Jim worked tirelessly as a financial planner to care for his beloved clients’ needs. Every day, he led by example through his dedication, work ethic and knowledge.

I met Jim in 1986. My co-worker, who was his college football teammate, introduced us. I was taken by his handsomeness, charisma, and understated confidence. I thought Jim came to our office to see his friend so I was surprised when a few weeks later he called to ask me out on our first date to the Huey Lewis and the News concert. We were instantly smitten and were married a year later!

Life with Jim Mohr was my biggest gift. I loved his passion for life, his abundance of energy, his love for adventure, his genuine kindness, compassion, and his warm laugh! As disciplined of a worker as he was, he had the ability not to take himself too seriously and made sure he scheduled in plenty of fun!

Jim loved the beach and was happiest surfing, body boarding and scuba diving. We were able to travel often and spending time with friends was important. Jim was the friend who would make sure to stay in touch with his high school and college friends and would be the organizer of their yearly reunions. He loved his annual boys surfing trips to Samoa, Fiji, Costa Rica, and Nicaragua where he was known to get barreled on a long board in the 10-14 footers acting like it was nothing! He was crazy brave.

We were blessed with three beautiful children; Michael, Kaitlin and Patrick. Raising our family was our biggest joy. Jim was very active with the kids and made sure his relationship with each of our kids was his top priority while running his business. Some of my fondest memories were all the neighborhood whiffle ball games and beach activities he organized for the kids. Jim was not only a father to our children, but as they grew up, he became a best friend and mentor as well. He was their rock and provided a supportive space as they faced life’s challenges. Our kids remark how he taught them to work hard and have a little fun, but more importantly he showed them how to treat everyone with love and kindness. Jim had a genuine way of making everyone he interacted with feel special and loved, a quality we all aim to embody in his absence. We were lucky to have such close relationships with our kids and make very happy family memories throughout the years!

In 2018, Jim and I were at a sweet spot in our lives where we were enjoying the fruits of our labors. Our children were adults and were thriving in their own lives, Jim was successfully in the process of transitioning his practice to our oldest son who had been working with him for the past several years, and we just bought a second home at the base of the Sierra Nevada mountain range near Lake Tahoe, Nevada. We were looking forward to enjoying all the activities that come with retirement: skiing, hiking, biking, travelling and future grandkids! Life was very happy and good.

It was in October of 2018 when Jim’s anxiety and insomnia became more frequent than in the past. We had just returned from Nevada and Jim was back in the office seeing clients. I distinctly remember one day seeing a frozen look of despair on Jim. I had never seen that look before on him. I asked what was wrong. Jim said, “I don’t know what’s wrong with me. I get this gripping feeling of anxiety that comes out of nowhere and it’s a terrible feeling.”

Thinking the cause was situational, I told him I was sure it’s the stress of coming back to work and getting back into the work routine. I shared how I was feeling stress about that as well. Jim had an annual checkup scheduled and his doctor prescribed an anti-depressant for the anxiety. I thought this was too aggressive a treatment, but Jim asked me to support him on this decision because he wanted to give it a try.

In December of 2018, Jim said he was feeling great. 2019 was a very happy year. Our daughter got married and we were enjoying our time in Nevada setting up our new home and enjoying all the fun activities of Lake Tahoe. Life was very happy and good… until 2020.

We started a big landscape remodel project in January 2020. Jim was very excited about this and poured his energy into all the details of the planning process. He would get up early and work all day with the crew. It was a labor of love for him. Everything he did, he gave 100 percent. I started to notice that Jim was having a difficult time remembering details that were discussed even with writing them down. Jim took frequent and detailed notes his whole life, but now he was slow in actually writing the notes.

On Mondays, we would have a morning meeting with the contractors. Jim was slower in his speech delivery and in his note writing so I offered to be the note taker. He shared with me how he was having a hard time understanding all the details of the project. He kept saying he was overwhelmed and felt confused. Thinking it was situational, I told him that I was confused with all these details as well but we will learn all the new systems we were installing. Looking back, I realize that in years prior, Jim never was confused about home improvement projects. He loved all the details and enjoyed every project.

A situation occurred that I felt was a “light switch” moment. The irrigation system we installed was having a water pressure problem. It was a frustrating situation, but Jim’s reaction was so uncharacteristic of him. Jim was a “there’s no problems only solutions” type of man. He came inside, hugged me and sobbed. I was stunned at his reaction. Jim was not afraid to show emotion, but this was not the reaction I was expecting.

The world then went into lockdown due to COVID-19 and his anxiety only intensified. Normally the voice of calm reason, he was feeling intense worry about the situation. Jim was experiencing severe insomnia which seemed to amplify the anxiety. His facial expression seemed to be in a constant state of worry. The whole world was in a state of anxiousness due to the pandemic, so I hoped his intense anxiety was situational.

Jim told me he thought he had early onset of dementia or Alzheimer’s Disease. He was worried about his constant state of confusion and memory loss. Having seen Jim’s beloved dad struggle with Alzheimer’s, I didn’t think that was the case because Alzheimer patients don’t know they are losing their memory. Jim’s symptoms of memory loss, confusion, anxiety, and insomnia worsened. The week prior to Jim’s death, I don’t think he slept more than two hours. I remember waking up and seeing a look of frozen horror on Jim’s face. I will never forget that look as it haunts me to this day. That was the face of severe suffering.

I began to realize there may be more to these “situational” symptoms. A few days later, Jim shared with me that as he was driving, he had to pull over because he didn’t know where he was or where he was driving to. He shared how he was fighting to control his feeling of anxiousness and it took him about 10 minutes to figure out where he was. That was when I realized I needed to pay attention and get some help. Jim agreed it was time to schedule an appointment with the doctor. I told Jim I was there to support him 100 percent.

Two days later, on May 10, 2020, Jim died by suicide. My family and I were devastated and shocked. He left a heartfelt letter which provided much insight on how he was struggling with depression, anxiety, memory loss, confusion, and pain.

Our oldest son, Michael quickly voiced his suspicions of CTE, and our family was in agreement to have his brain studied. Jim shared with Michael a few years earlier how he was worried he may suffer from CTE in the future due to all the times he “got his bell rung.”

Researchers at the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank diagnosed Jim with Stage 3 (of 4) CTE. I cannot express how grateful I am to the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank study and to the Concussion Legacy Foundation. The CTE finding helped me understand why Jim suffered the way he did before his death. When I was waiting for the findings, I found it so very helpful to read other Legacy Donors stories. I found similarities and differences in how CTE symptoms present. Those stories shed light on a subject I was unaware of and yet living with in plain sight. Jim hid his symptoms until he couldn’t hide them anymore as CTE took over.

So many times after hearing someone died of cancer, I see “After a brave fight, they lost the battle to cancer.” I believe all victims of CTE fight a brave fight. It’s just a battle that ultimately feels like it can’t be won at this time. As family members affected by CTE, we can help to prevent the battle. We can keep telling the stories of our loved ones.

Jim Mohr loved the game of football and he would want to save the game. Jim once said, “Living with constant anxiety is horrible and I hope none of you experience it.” Tackle CAN and SHOULD wait if we want to reduce the risk of CTE among football players.