Chad had an outstanding athletic career. He began playing football at ten years old at Dexter School, a boys private day school in Brookline, Massachusetts. He was selected to the State Boys soccer team and played varsity hockey and football at Noble and Greenough School. He then went on to become a three-year starting varsity defensive back at Columbia University. After college, Chad took up tennis and participated in the U.S. Father and Son Championship at the Longwood Cricket Club with his father. Later in life, he became an avid golfer.

Chad was one of the brightest people I have ever known. Chad was a precocious reader with an exceptional curiosity about everything from the evolution of all living creatures, the geographic wonders of the earth, the significance of studying ancient cultures and architecture, and even the evolution of ethics and moral behavior.

When he was ten years old, we visited the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston to see the Pompeii exhibit. He described the experience as the moment when he knew he wanted to study the history of Roman and Greek civilizations. He would continue this passion and go on to major in the Classics at Columbia University.

He would often tell the story about how he chose this study. He called me one evening and said he needed to declare his major and I asked him what really interested him. He said, “Latin and Greek.” I said go for it and he said, “Well, it will not get me anything except maybe being a pharmacist with Latin words for prescriptions.” We laughed when, in the fall playing varsity football at Columbia, the coach said they did not know how to help him through the semester since no one had ever played football and majored in the Classics.

His passion for ancient civilization led him to travel extensively in and around Italy and Greece, visiting remote sites, particularly lesser-known ruins in Sicily and out of the way Greek islands. His scope of knowledge was extraordinary. He could converse for hours on subjects from the Roman poet Catullus to Grecian urns. His enthusiasm for Greek and Roman architecture and sculpture was contagious. I will treasure his intellect and his enthusiasm for sharing his repository of knowledge.

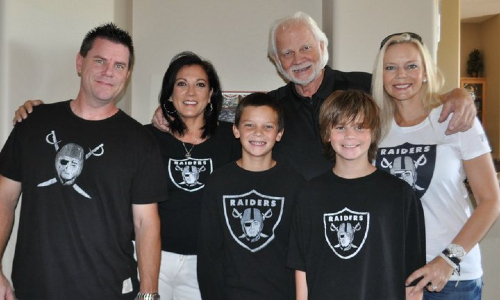

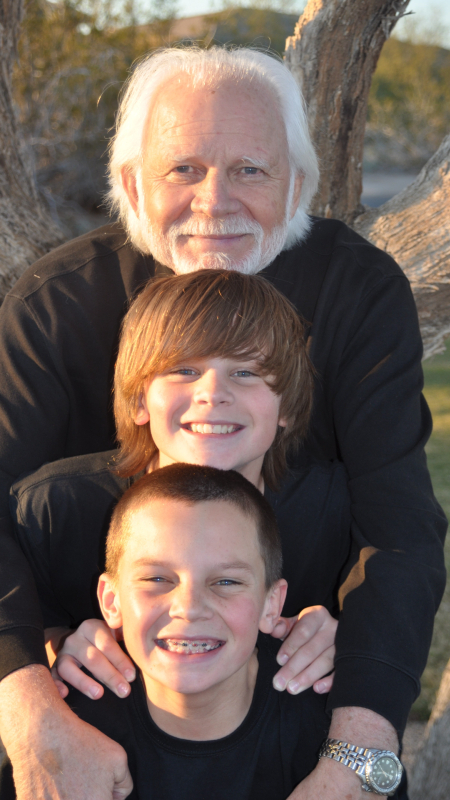

I will forever remember how wonderful he was to his two younger brothers, Adam and Gavin. They recall at ages 10 and nine travelling with Chad to New York to visit me in the hospital. They remember visiting his fraternity at Columbia, thinking how cool it was that there were so many video games in his room. They remember him taking me out of the hospital and taking us all to dinner.

I will cherish his letters from summer camp in the Adirondacks. I will cherish our pack trip to the Tetons, sleeping in the wilderness and fishing on the Snake River. I will never forget his face when I drove him to his first away game at Thayer Academy as a freshman at Noble and Greenough School. The boys on the Thayer team were all powerfully built, and he looked at me and said, “Those guys are really big. How am I going to handle this?” Then, just like that, he looked me in the eye, winked and got out of the car.

When, where and how did he devolve into an addict and alcoholic and lose his job, his home, and his relationship with his siblings due to his raging and violent behavior?

Did his CTE begin when he was 15 or 18 or did it begin when he was younger? What was the tipping point? When did his sometimes-arrogant intellect morph into narcissistic sociopathic behavior?

When did his aggressive behavior frighten us to the point where my other sons did not want me to see him alone? He blamed his addiction on my father who was an alcoholic. He blamed it on the opioids he was prescribed after a football injury at Columbia.

Did he know something was wrong? Was there anything we could have done? Were there warning signs? After enabling him for years, my family suggested I not see him. He continued down the path of his addiction, which became primarily alcohol.

He befriended an elderly woman named Ruby in his neighborhood who used to drag him off the curb after one of his routine binges. She became his substitute mother and tried to get him help to no avail. What were the demons in his brain?

Sadly, by the time he wanted to try to stop drinking and work his way back to recovery, his liver was failing. He bought a fancy juicer and would call me and ask how to make healthy smoothies. He tried to cook and eat healthy, again calling me to talk him through recipes.

We spent last summer trying to get him on a liver transplant list, but his body was not able to recover. He was in and out of the hospital until he was too weak to be on his own. When the liver fails, everything breaks down and he had to suffer through painful belly drainage every few days as his liver was not able to remove toxic waste.

To the end, he never discussed dying but three days before he passed, as I sat next to his bed, he reached over and brought my head into his chest and hugged me. He said, “I love you.”

He died on a summer afternoon at Massachusetts General Hospital two hours after I kissed him goodbye. I am not sure what made me decide to donate my son’s brain to Boston University’s CTE Center, where researchers diagnosed him with stage 1 CTE. It seemed this would be a way for his life to go on having meaning. But maybe it was also that I wanted to know what happened to bring him to this tragic end. Somehow, I wanted his life and incredible mind to have been for something greater than his death.