Curtis Sellick

Stephanie Servis

Dennis Shippey

Beloved husband, father, son, brother and Coach

Growing up in Davenport, Iowa, Dennis L. Shippey knew what it was like to get up and go to early morning swim workouts. For him it was fun and little did he know that the sport of competitive swimming would become his passion, his career and his friend.

Once he entered Davenport West High School (’62), Shippey quickly became a state figure in swimming. He was state swimming champion in breaststroke and runner-up in the 200 Individual Medley. His accomplishments placed him as an All-American swimmer in the breaststroke for two consecutive years. In 1996, Dennis was inducted into the Iowa Sports Hall of Fame as a high school swimmer athlete.

After high school, Dennis accepted a swimming scholarship to Eastern New Mexico University (Portales, NM). There he majored in health and physical education. This Greyhound swimmer went on to become an NAIA All-American breaststroker and champion.

When Shippey graduated from ENMU in May 1969, he was drafted into the Army. In 1970, Dennis and I married. Shortly thereafter he was drafted and proudly served with the 101st Airborne Division in Vietnam. After military service, Dennis entered the Master’s program for Health and Physical Education at the University of Northern Iowa. As part of a graduate internship with the university, he served as the assistant coach for swimming and diving while completing the program.

From graduate school, Shippey moved to Elkhart, Indiana, where he was head coach for swimming and diving at Elkhart Central high for two years before relocating to Texas in 1976. In August of 1976, he moved his family to Pasadena where he would coach both boys’ and girls’ swimming. Coach Shippey remained in this position until retirement. Actually he held a dual assignment for Pasadena ISD as coach and aquatic coordinator from 1988-2004.

During the years at J. Frank Dobie High School, Coach took numerous swimmers to state competitions in Austin. His teams won District Championships and showed good standings at the Regional competitions. He was honored on more than one occasion as District Swim Coach of the Year for Boys and District Swim Coach of the Year for Girls.

At 55-years-old, Dennis was diagnosed with Early On-Set Alzheimer’s. With that diagnosis came a shocking reality of what life had in store for him and for us. With the support of doctors and our district, Dennis was able to work 1.5 years after the diagnosis. Then at that point there were obvious indications that he was struggling with the daily routine of coaching and being director over the district swim programs. So in 2004, Dennis retired and was honored by over 200 former swimmers and swim parents at a Retirement dinner. Most who attended gave testimony to the impact Coach had on their personal lives. Then in 2007 Dennis was honored by the Texas Swim Coaches Association with the Theron Pickle Lifetime Achievement in Swimming award. At a state conference in Austin, Shippey was presented with a coveted ring than only 7 recipients had received before him.

Dennis never accepted his diagnosis. He knew he had some memory problems, but maintained his determination to live life to its fullest. Through swimming and biking he maintained his mental and physical abilities. He started swimming in the YMCA, United States Masters and Senior Games competitions at the state and National level. With Senior Games he became a national champion and was inducted into the Texas Senior Games Hall of Fame in June 2011 (the first swimmer for that state). In US Masters swimming he achieved All-American status on a national championship relay while competing with his best friend, Bruce Rollins, on the The Woodlands Masters team. With the help of Bruce, Dennis competed as a national champion at the YMCA Nationals in Florida. Shippey’s highest honor was being recognized as Top Five in the World FINA rankings in 2008. That statistic was revealed at the Hall of Fame Banquet in Bryan, Texas.

Doctors, family, and friends believe that the progression of Alzheimer’s was held back by Dennis’ athleticism and desire to keep active. With the help of his best friend, Bruce, he entered every swimming competition available. The two traveled as a team until the last 18 months when Dennis could no longer travel safely and follow the process of competition.

When Dennis was not swimming, he was biking. With the help of his son, Scott, Coach Shippey rode the 2005 RAGBRAI (444 miles, 7days across the state of Iowa). So, the normal routine for any given day of retirement at the Shippey house was a bike ride in the morning then a swim workout with the high school kids in Pasadena.

Throughout the years of treatments, doctors continually questioned their diagnosis. They did not believe Dennis had the profile or conditions of Alzheimer’s, but there was no other explanation or known treatment.

The last 18 months of Dennis’ life were met with wandering on foot over 40 miles from home and being found near death in a field 3 days later; an unrelated hospitalization that put him in the hospital for 9 weeks experiencing respiratory arrest on ventilator followed by extensive blood clots in both legs; extreme aggression against loved ones and finally placement in a specialized dementia care facility where he died in August 2011.

In June 2011, as a way to honor the legacy of his dear friend, Bruce Rollins nominated and presented Dennis with the Texas Senior Games Hall of Fame Award at a state banquet. This was just a few weeks before his death but he was able to attend surrounded by family.

Six weeks before Dennis’ passing, I received information about brain donations with the Concussion Legacy Foundation. I had tried for over one year to find a place for donation and nothing was readily available. It was amazing to me that this brain-donation program would solicit brains with no concussion histories to be used for control purposes. Our family wants to thank Dr. McKee, Dr. Stern, and Dr. Nowinski for their global research in searching for answers that can help families in the future.

Dennis Shippey is survived by his wife, Linda (Pearland, Texas), son Scott, wife Melissa, and grandchildren Luke and Mia (Austin, Texas), as well as his daughter Sondra and her children Ian, Aaron, and Hannah (Pasadena, Texas).

Robert Shisslak

Much to my disgust, he put peanut butter on his pancakes and ketchup in his macaroni and cheese and was still the person I named as my hero in Kindergarten. Robert Shisslak could strike up a conversation with absolutely anybody and it is something my mother always tells me I inherited. He raised me on the Oldies on vinyl, Ford trucks, fishing and Forrest Gump but still refused to buy me a Nerf gun because I’m a girl. He also told me I would be going to military school and be unable to date until I was 35. After throwing many temper tantrums because I actually believed he would ship me off to the Navy, I can say that while I’m proud of our Navy and my dad, the thought of even basic training terrifies me. By the time I got my first boyfriend, Dad could not do much about it since he was already gone. Dad died on April 12, 2011 and I still half expect him to walk through the door with a BJ’s bag full of useless things we will never use; but hey, they were on sale!

I asked our daughter Abigail to write a short little something about her dad and in less than 5 minutes she wrote the above paragraph. She captures her dad in the perfect light. My husband of 14 years and 10 months was the kindest man I knew and the type of guy who would give the shirt off his back to someone who needed it.

Robert (Drew as he was known to his family and friends) grew up in Central and then Western Pennsylvania, the youngest of 4 children and the only boy. He entered the Navy right after high school. He often told stories of his days living on an aircraft carrier. Following his military career, he became employed at McDonnell Douglas where he was chosen to be a part of the Space Shuttle Endeavor assembly team. Robert also had the gift of being a good listener. Robert was a Court Officer for the Massachusetts Trial Court where he would often encounter newly arrested individuals who just needed someone to listen.

Robert was everybody’s friend, but to me, he was my one-of-a-kind husband, companion, best friend, the father to our wonderful and beautiful daughter who can never be replaced.

Chad Short

Brent Simpson

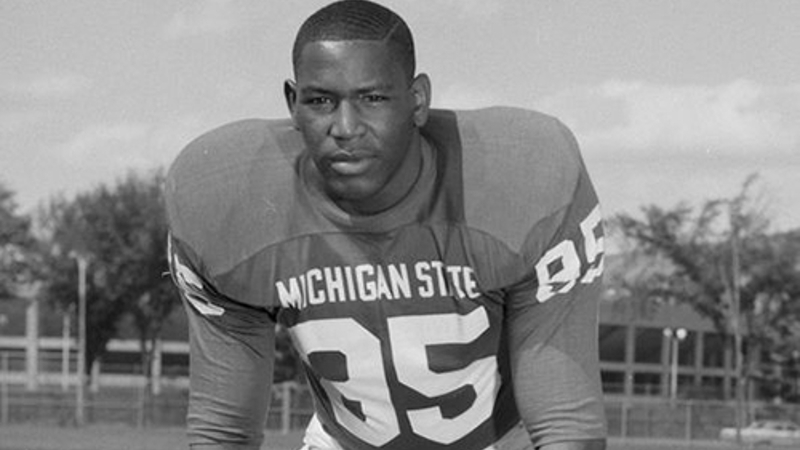

Charles “Bubba” Smith

Read this excerpt from Spartan Verses by Pat Gallinagh; edited by Jim Proebstle, author of Unintended Impact.

Pat and Jim were teammates of Bubba’s at Michigan State University during the 1965 and 1966 seasons, when they won back-to-back National Championships.

Every now and then you run into a character who is “bigger than life.” Charles “Bubba” Smith of Beaumont, Texas at 6 ft. 7 in. and 270 lbs. did both literally and figuratively fit that mold. Bubba was a passenger on the “underground railroad” of talented black athletes from the Jim Crow south that prohibited players from playing in the South. He, along with many others, was actively recruited by Coach Duffy Daugherty of Michigan State University in the sixties in what was to become one of Duffy’s hallmark achievements. Given a choice, Bubba probably would have preferred playing at a major university in his home state, like the University of Texas or Texas A&M.

By far the biggest member of the Spartan freshman football team in 1963, it was impossible for him to blend in with the thousands of new students pouring into East Lansing from all over the world. He stood out like a giant oak in an apple orchard. Many students stared at him in disbelief and rather than shy away from the fact that he was a behemoth, Bubba played the role to the hilt using his comedic talent to pretend to be a dim-witted, bumbling, good-natured oaf. A skill he would parlay into a successful acting career in Hollywood. He was a teaser and practical joker pushing his teammates’ buttons and his coaches to their limits with his pranks. In reality, Bubba was a good friend to those around him and never actively sought out the notoriety that just naturally presented itself.

There were some members of the college community who thought football players were modern day Neanderthals who dragged their knuckles on the ground as they prowled the campus. Others felt the football scholarships were a form of color-blind affirmative action for the intellectually challenged. Bubba was neither uncivilized nor stupid, although his persona did often catch the attention of the administration and coaching staff as his celebrity peaked during his senior year. The many Bubba sighting and urban legend stories that still exist to this day on the MSU campus are telltale of a man who easily adapted to the “big stage.”

With his enormous physical talent, he was often accused of not using it to the fullest on the field. There may have been some truth to that at times, but if so, it probably had more to do with peer pressure than not making an effort. When you are the biggest kid in your class you are often chided for using your superior strength and size by your classmates. Being labeled a class bully was not a coveted title back then or now, so unless prodded to do so by teammates or coaches, he sometimes may have appeared that he wasn’t trying very hard. And, it may have been because he didn’t have to. We should ask Terry Hanratty, Notre Dame’s QB who was permanently knocked out of the 10-10 Game of the Century, what he thought after a crushing tackle by Bubba in 1966. In any event, most teams ran their offense away from him as the fans in the stands chanted, “Kill, Bubba, Kill.” In the locker room Bubba was a very unique actor and just one of the guys adding tremendous chemistry and humor to a determined team of athletes.

The pros knew what they were doing when he was selected as the number one draft pick in 1967. He helped lead Baltimore to two Super Bowl performances in his five years with the Colts, winning Super Bowl V in 1971. After the Colts he spent two seasons each with Oakland and Houston. As one of the best pass rushers in the game, Bubba often drew two blockers, yet was effective enough to make two Pro Bowls, one All-Pro team and be recognized through the Vince Lombardi Trophy. Bubba Smith was enshrined in the College Football Hall of Fame in 1988. The Big Ten Defensive Lineman of the Year Award bears his name. It is not documented to what extent he experienced concussions during his playing years. Clearly, there was significant punishment. What is known, however, is that the Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) discovered in Bubba’s brain by neuropathologists at Boston University Medical Center was classified as Stage III CTE with symptoms that included cognitive impairment and problems with judgment and planning. Bubba died on August 3, 2011 at the age of 66. Smith was the 90th former NFL player found to have had CTE by the researchers at the UNITE Brain Bank out of their first 94 former pro players examined.

He was likely on his way to the NFL Hall of Fame until landing on a sideline marker in an exhibition game that curtailed his playing career and headed him into his acting career. Between 1979 and 2010, Bubba appeared in various roles in over twenty-two movies and television performances. Probably his most noteworthy efforts came in his role of Moses Hightower in the Police Academy movies and his role with Dick Butkus in the “taste great…less filling” Miller Lite commercials. It was this beer commercial contract that led to his proudest moment. When he realized that he was being used as an instrument to promote drunkenness; he walked away from his contract. His matured social consciousness took both strength and courage to break such a lucrative deal. He valued integrity over money. In the final analysis he was just Bubba: friendly, easy to approach, generous and never getting “too big” as a result of his success.

Bubba Smith is survived by his son, Nathan Hatton.