By Dr. Chris Nowinski, Concussion Legacy Foundation co-founder and CEO

For years, the erratic behavior of NFL All-Pro wide receiver Antonio Brown has been a cause for concern as many have watched and worried for his mental health. In Sunday’s Tampa Bay Buccaneers game, Brown had another episode of abnormal public behavior. After a sideline dispute with Bucs coaches, he took off his shoulder pads and jersey, threw his shirt and gloves into the stands, performed jumping jacks for the crowd, and walked off the field. He is no longer a member of the team.

Full video of Antonio Brown quitting in the middle of the game ????

????: @mmmmillah

pic.twitter.com/Bwi9yPACJ6— PFF (@PFF) January 2, 2022

A lot of people are worried and speculating that Antonio Brown is exhibiting signs of CTE. As a CTE researcher and CEO of the Concussion Legacy Foundation, I’d like to use this opportunity to educate the public on what we do know about the disease and how it progresses.

Like you, I wonder if Antonio Brown’s behavior is caused by CTE. We can’t know for sure today, because CTE can only be definitively diagnosed after death. However, the recent diagnosis of CTE in two former NFL contemporaries of Brown’s, Vincent Jackson and Phillip Adams, can provide insights into the two separate but related questions we’re trying to answer: does Antonio Brown have CTE and is it causing his destructive behaviors?

Question 1: Does Antonio Brown have CTE?

Vincent Jackson’s story gives insight into whether Brown may have CTE. Jackson was a 3-time Pro Bowl wide receiver for the Tampa Bay Buccaneers and the San Diego Chargers from 2005-2016. He was found dead in a hotel on Feb 15, 2021 at the age of 38.

Jackson’s brain was studied by Dr. Ann McKee at the VA-Boston University-Concussion Legacy Foundation Brain Bank, where she discovered he had stage 2 CTE.

Previous work from the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank has shown that the odds of developing CTE are not statistically related to how many concussions you have, but instead correlates with how many years of football you play. A football player’s odds of developing CTE go up by as much as 30% per year. Vincent Jackson started playing football at age 12 and played 11 years in the NFL.

Antonio Brown has now played 12 years in the NFL and according to ESPN started playing tackle football before high school, meaning he likely played more years than Vincent Jackson. On top of the years he’s played, Brown ranks 21st all-time in receptions, which means, among wide receivers and tight ends, he’s also among the most tackled NFL players of all-time.

In 2019, when Brown was asked if he had CTE, he told ESPN:

“If I had CTE I wouldn’t be able to have this beautiful gym, I wouldn’t be able to be creative. I wouldn’t be able to communicate. I’m perfectly fine.”

Those comments illustrate a fundamental misunderstanding of CTE. Later stage CTE (stage 3 and 4) is associated with dementia, but early-stage CTE (stage 1 and 2) is more associated with what is called neurobehavioral dysregulation, which includes violent, impulsive, or explosive behavior, inappropriate behavior, aggression, rage, “short fuse,” and lack of behavioral control.

Brown went on to say, “I didn’t take that many big hits. I had like one big hit in 10 years. Anybody who plays this game, they’re going to get hit hard. He didn’t hit me that hard. You know, I got up and walked off the field.”

Brown’s words are eerily similar to a statement Jackson made two years before his death when asked about CTE: “I was fortunate, trust me. I never took many major hits.”

The big hit Brown is referring to is the one below from Vontaze Burfict in 2016, which caused loss of consciousness and therefore by definition caused a significant traumatic brain injury (TBI).

I’m no doctor, but maybe Antonio Brown never recovered from this disgusting hit by Vontaze Burfict pic.twitter.com/7FKGRs9AiD

— Eric Rosenthal (@ericsports) January 2, 2022

Independent of whether Brown has CTE, TBI is also associated with acute onset of similar neurobehavioral symptoms. It’s plausible that the TBI could account for his abnormal behaviors since then.

However, the more concerning reality for all of us former football players is that it’s not the big hits, but the accumulation of all the smaller hits we never thought about, that cause CTE. 20% of former football players diagnosed with CTE have never had a formally diagnosed concussion.

Finally, it’s important to note that CTE is extremely prevalent among NFL players. A 2017 study from the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank revealed that 1 in 10 of the NFL players who died between 2008-2015 were diagnosed with CTE, and 99% of the 111 players studied had CTE. Accounting for the fact that families that noticed severe symptoms are more likely to donate, it’s likely a minimum of 10% of NFL players have CTE, and it could be many, many times higher.

Question 2: If Antonio Brown has CTE, is it causing his destructive behavior?

CTE was largely ignored by the medical community for the 80 years after Dr. Harrison Martland published Punch Drunk in the Journal of the American Medical Association in 1928. Therefore, we are still learning what symptoms are directly caused by CTE.

The evidence strongly suggests that stage 4 CTE causes dementia in most cases, but it’s not so clear which symptoms are regularly caused by early-stage CTE. But it would not be surprising if we eventually prove that the earliest stages of CTE are associated with an increased risk of psychiatric symptoms. A study on the earliest stages of Alzheimer’s disease found that pathology in the locus coeruleus (early-stage CTE also impacts the locus coeruleus) is associated with increased depression, anxiety, and sleep disorders.

What we have shown about CTE is that stages are most associated with age. That means everyone starts at stage 1, with microscopic CTE lesions in their brain, while they are getting exposed to repetitive head impacts, usually as a teenager or in their 20s (CTE has been confirmed in people as young as 17).

CTE then spreads to adjacent tissue and new parts of the brain, progressing at different speeds in different people due to differences in exposure, genetics, and more. Most football players who die in their 30s are diagnosed with stage 2 CTE. Aaron Hernandez was the youngest football player diagnosed with the more advanced stage 3 disease when he died at 27.

Earlier this year, former NFL player Phillip Adams shot and killed 6 people, including two young children. Adams then turned the gun on himself and died at the age of 32. His brain was studied by Dr. Ann McKee at the BU CTE Center, and she discovered he had stage 2 CTE with abnormally severe damage to the frontal lobe of the brain.

Investigators said they never found a motive for the murders. Toxicology revealed Adams was not under the influence of any substances at the time of the murders. Police reported finding numerous notebooks with “cryptic writing with different designs and emblems,” and his sister said his behavior had changed dramatically over the last two years.

“His mental health degraded fast and terribly bad,’’ Lauren Adams told USA TODAY. “There was unusual behavior. I’m not going to get into all that (symptoms). We definitely did notice signs of mental illness that was extremely concerning, that was not like we had ever seen. He wasn’t a monster. He was struggling with his mental health.”

When asked if the killings could be explained by CTE, Dr. Ann McKee said, “Severe frontal lobe pathology might have contributed to Adams’ behavioral abnormalities, in addition to physical, psychiatric and psychosocial factors. Theoretically, the combination of poor impulse control, paranoia, poor decision-making, emotional volatility, rage and violent tendencies caused by frontal lobe damage could converge to lower an individual’s threshold for homicidal acts — yet such behaviors are usually multifactorial.”

Phillip Adams and Antonio Brown were born 10 days apart and were both NFL rookies in 2010. But Adams had retired by 2015. Brown is still playing.

Answering the Question:

Based on everything we know about CTE today, it is possible that Antonio Brown has CTE, and that CTE is causing his behaviors. But you already knew that.

The bigger question is what do we do with this information?

First, we need to invest more in preventing and treating CTE.

Football is less obviously dangerous than it was in years past, with a number of rule changes introduced designed to reduce concussion risk and concussion protocols. But that doesn’t mean we’ll see a reduction in future cases of CTE. Most of the reforms made focus solely on concussion, not reducing CTE. And what’s not said enough is that all the changes may be completely offset by the fact that football players at every level are bigger, stronger, faster, and therefore creating higher magnitude impacts and more CTE. Even Junior Seau’s CTE now looks mild compared to more advanced cases we are now seeing in college football players who died in their 20’s.

We don’t invest nearly enough in learning how to meaningfully treat CTE, which not only impacts athletes but also military Veterans and victims of abuse.

In 2015, the NFL pulled $14 million from research designed to learn how to diagnose CTE. To wipe that headline off the front page, the NFL quickly announced a $100 million donation to brain research, but only put a few million of that towards CTE research, instead putting $60 million toward safer helmets, which isn’t going to make much of a difference in CTE but creates hope and headlines. (Did you hear about new position-specific helmets?) When you think about helmets and CTE, think about trying to prevent automobile deaths by only investing in better bumpers. It’s such a small piece of the puzzle.

Second, I think Tom Brady had it right when he said, “I think everyone should be very compassionate and empathetic towards some very difficult things that are happening.”

Antonio Brown’s mental health has been unraveling on a public stage for many years. CTE could be the cause of everything. Or it could not.

But that doesn’t change the fact that a staggering number of former football players, contact sport athletes, military Veterans, and others are suffering from CTE, and we don’t have answers.

At the Concussion Legacy Foundation, we’re trying to get those answers before it’s too late.

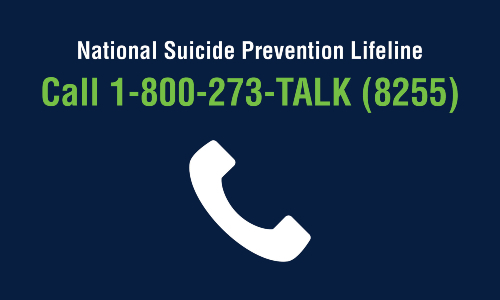

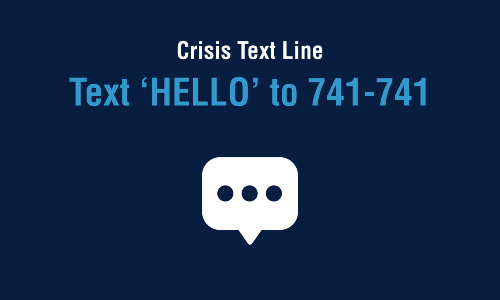

What we do know right now – and what we want to make very clear to Brown and anyone else like him who may be reading this: help is available. CTE is not a death sentence. Just because you have years of exposure to repetitive head trauma does not mean you are destined to exhibit certain behaviors. There are ways to take control of your brain health and we have a team at CLF ready to teach you how. Our HelpLine staff is filled with caring individuals who are here to assist patients and families suffering with CTE symptoms. We can connect you to treatment in your area and providers who understand what you’re going through. You are not alone.

If you’d like to join us in the fight against CTE, there are several ways to get involved. If you’d like to donate your time, sign up to participate in research. If you’d like to learn about the easiest way to prevent CTE, learn about Flag Football Under 14. If you’d like to make a donation, click here. If you’d like to stay educated on CTE, sign up for our newsletter.