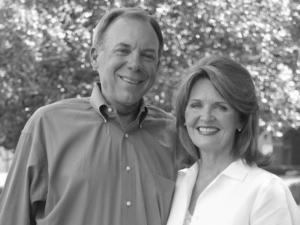

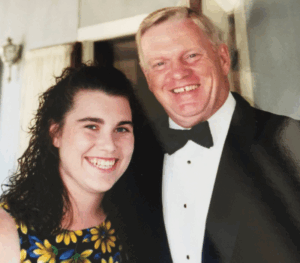

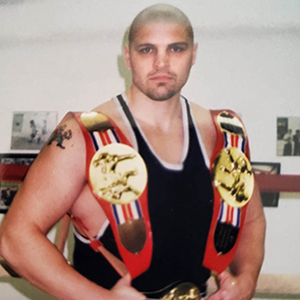

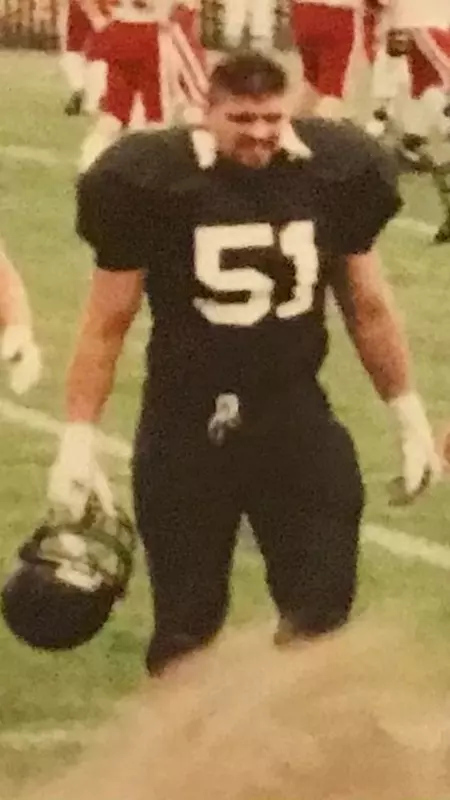

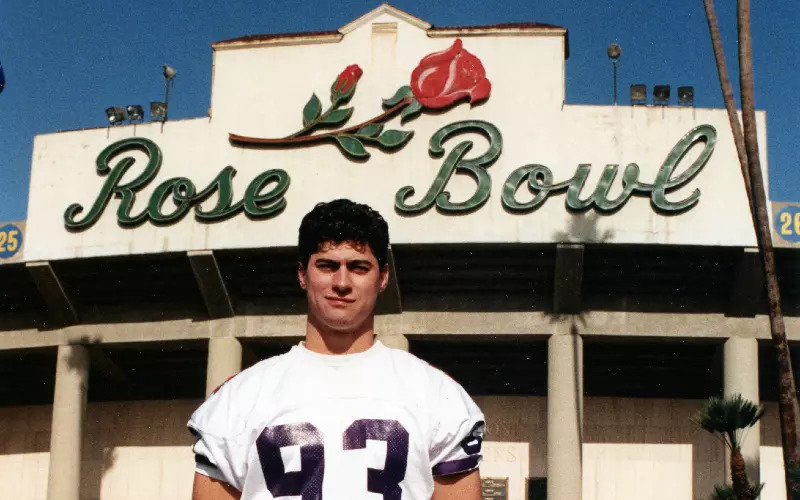

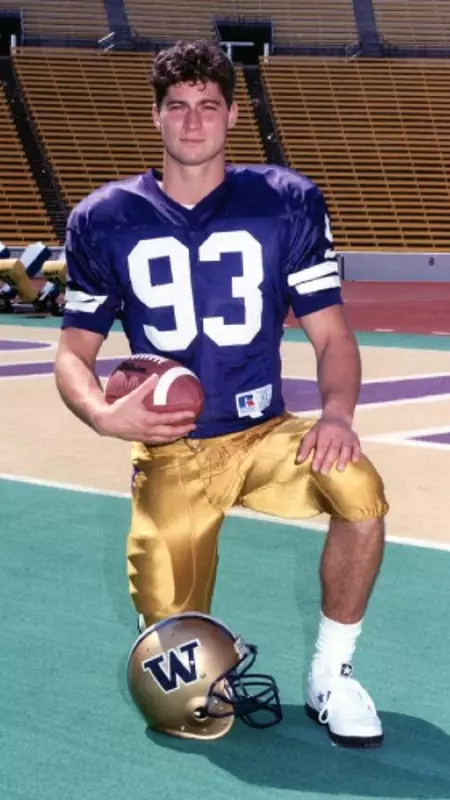

Retired Lieutenant Colonel Robert Gowan experienced a substantial share of head trauma during his athletic and military careers. He grew up playing football in Houston, Texas before walking on to the football and rugby teams at the Virginia Military Institute. This was in the 1980’s, well before concussions were widely regarded as a serious injury.

His sports teams were “old school” and prioritized toughness. For Gowan and his teammates, that meant playing through pain and leading into tackles with their helmets.

One of the earliest concussions Gowan can remember came during a high school playoff game in the Houston Astrodome.

“It was a toss sweep to their running back on my side. When I made contact the lights went out,” said Gowan. “I don’t remember the hit or much after it besides looking up at the scoreboard and seeing sparks and stars flying toward me, but I finished the game. Back then if you weren’t knocked out cold and put on a stretcher you got on your feet and kept going.”

Gowan has several similar stories, as do some of his former teammates. The common factor: if they could hide their symptoms enough to continue playing, they did. Gowan’s military experience was no different.

Decades of Service

Inspired by his father and grandfather’s service, Gowan knew he was interested in joining the Army after college. In May 1988, he was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the U.S. Army.

Gowan’s 25-year military career took him all over the world. His first major assignment was in Germany at the tail end of the Cold War. Serving as a nuclear weapon technical operations officer, Gowan witnessed the toppling of the Berlin Wall, the reunification of East and West Germany, and the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Gowan took on various roles at bases throughout the United States, Korea, and Kuwait, earning jumpmaster status and commanding an artillery battery for the 82nd Airborne Division along the way.

By the time of the 9/11 attacks, Gowan was a seasoned officer. The historic events that followed, including the U.S. invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, marked a momentous shift in his career. By 2003, Gowan was serving his first tour in Iraq.

“My military career was bisected by the events of 9/11. Everything became focused on supporting combat operations in Iraq and Afghanistan” said Gowan. “The second half of my career was very serious and intense. I saw a lot of casualties and fatalities in the men and woman I was providing support to.”

It was a new chapter in Gowan’s service and a life-changing experience. He remained committed to the Army and redeployed to Iraq in 2007 as part of a surge in U.S. Military presence before taking a post in Afghanistan in 2009. Gowan witnessed and personally experienced significant brain trauma throughout his career until retiring in 2014.

Common Brain Trauma in Military Service

Gowan knew about concussions from sports, so he was able to recognize their hallmark characteristics during military training and deployments.

At U.S. Army Airborne School at Fort Benning in 1989, for instance, Gowan landed hard during the final training jump before graduation.

“When I stood up, I was seeing double,” said Gowan. “I knew something was wrong, but I didn’t seek medical attention because it was my final jump of Airborne School. I recovered quickly enough to just move on, put it behind me, and head to Germany for my first duty assignment.”

Shaking off rough impacts was the norm. In fact, hard landings were common enough in the Airborne community that they have a saying about it: “feet, butt, head.” When a landing went wrong, usually your feet hit first, then your butt, then your head. The saying is a common reference among paratroopers to help brush off rough landings, which were often unpredictable, uncontrolled, and forceful.

Some jumps go off without a hitch, like the time Gowan completed a midnight jump onto an airfield in the mountains of northern Iraq with the 173rd Airborne Brigade, and some don’t. Even less technically challenging jumps can go wrong. Gowan’s daytime jump with the 82nd Airborne Division at Fort Brag in 1997, for example, was a comparably routine jump. At the time, Gowan was a battery commander leading a training mission. When he landed – feet, butt, head – he recognized another hallmark concussion symptom in himself.

“I remember thinking oh, boy, that was bad,” said Gowan. “As I regained awareness, I tried to speak, but I couldn’t because my speech was temporarily slurred. My first thought was that I knocked out all my teeth or broke my jaw, but when I felt they were intact, I realized it must be the hit to my head.”

Gowan felt like he didn’t have the luxury to pursue medical aid because he was in charge, so he proceeded with the mission. Gowan recovered quickly, completed the mission, and moved on. In hindsight, Gowan wishes he’d told the medical team.

Now that Gowan is retired, he wonders about the cumulative effect of these and several more traumatic incidents and how they impact his life today.

“I have concerns about the long-term effects. I have some memory issues and I have been diagnosed with PTSD,” said Gowan. “When you’re in a combat zone, you see and experience things that you can’t shake even if you want to. It’s hard to draw a direct line from a concussion or traumatic experience to later changes in functioning but the uncertainty, or the possibility, is hard to wrestle with.”

Gowan is familiar with Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) and knows that sub-concussive impacts, impacts to the head or body that don’t cause obvious concussion symptoms, can bring substantial long-term complications.

“I was on the delivering-end of mortar rounds in trainings, but I was on the receiving-end of mortar fire in Iraq. It’s hard not to worry about those blasts now,” said Gowan. “I was in Basra for just a few days in 2007 as part of a JSOC [Joint Special Operations Command] leadership recon and we got hammered by repeated mortar shelling. One blast in particular was so great if felt like my teeth were going to blow out of my head.”

Today, we understand better the risks soldiers who operate artillery, mortars, and anti-armor weapons are exposed to from concussive blasts and know TBIs are happening often. According to the Defense and Veteran Brain Injury Center (DVBIC), 414,00 TBIs were reported among U.S. service members between 2001 and late 2019.

“We know it’s a problem. The military has been studying this and working to minimize risks, but it is a big concern,” said Gowan.

Military training also comes with significant risk for injury. Servicemembers are asked to prepare for realistic situations.

“Military training is inherently dangerous,” said Gowan. “Whether you are training in vehicles, parachute jumps, combat simulation, or land navigation you tend to get banged around. You suffer trauma to various parts of your body.”

Retirement has given Gowan time to reflect on his own injury history, the servicemembers he worked alongside, and what the military community can do to prevent the worst outcomes of cumulative brain trauma.

Observations in a Combat Theatre

Beyond his own injuries, Gowan witnessed large scale combat and casualty trends in Iraq and Afghanistan after the introduction of improvised explosive devices (IEDs).

Gowan finished his first deployment in Iraq right as IED attacks were becoming more common. Initially dubbed “roadside bombs,” IEDs were a bigger problem when Gowan went back in 2007.

“That was how the enemy seemed to be most effective fighting against U.S. and coalition forces,” said Gowan. “When I was there in 2003, we didn’t have ‘up armored’ Humvees. As IED casualties became more common, the Army adapted.”

Beyond his own time in combat theaters, Gowan learned that a close friend from early in his military career at Fort Bragg was injured in an IED attack, losing both of his legs. Another servicemember close to Gowan, one of the ROTC cadets he mentored as an instructor at the Virginia Military Institute, suffered a severe TBI from an IED in Afghanistan.

“I know of a lot of exceptional men and women that were wounded and suffer from the effects of TBI. The issue hits very close to home,” said Gowan.

A 2017 study on post-9/11 veterans showed explosive blasts were the leading cause of reported traumatic brain injuries in Iraq and Afghanistan. Regardless of injury source, it is a staggering fact that 414,000 of the 2.7 million total troops deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan have been injured by TBI. Considering not all TBIs are reported, the proportion is likely even higher.

“I came into contact with a lot of people who were real heroes,” said Gowan. “I’m no combat hero and would never represent myself as such, but I was in close proximity to those men and women in support operations. I’ve seen and still feel the weight of their sacrifices.”

A New Mission After Retiring

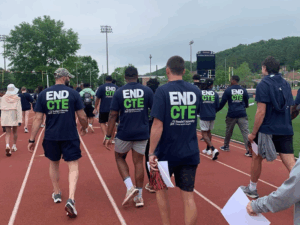

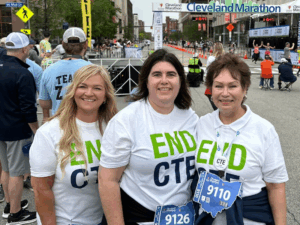

Gowan is grateful for his military career. Now, on the other side of service, Gowan is passionate about finding ways to improve the lives of service members impacted by brain trauma. That passion led him to Project Enlist. The goal of Project Enlist is to accelerate critical research on TBI, CTE, and PTSD in military veterans.

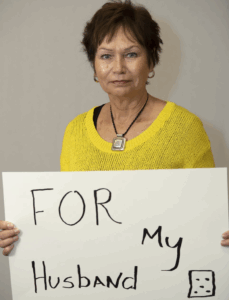

Gowan is giving back by pledging to donate his brain to the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Boston University, Concussion Legacy Foundation (VA-BU-CLF) Brain Bank. This gesture helps to raise awareness about the need for research and directly contributes to scientific breakthroughs in our understanding of military brain trauma.

“I’m an organ donor. I believe it’s a good thing to help other people after you’re gone,” said Gowan. “So, when I heard about being a brain donor for CLF, it was a natural thing for me. There’s still so much we need to learn about the effects of trauma and sub-concussive blasts.”

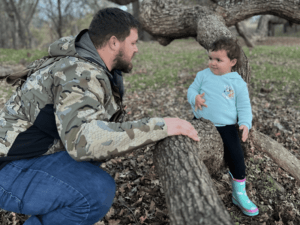

Gowan is recruiting other veterans to support Project Enlist because he feels the urgent need for this research. Many veterans, like Gowan, are also former athletes with previous brain trauma.

“I think about how so many military service members are also former athletes.” Gowan said. “I have an interest in the TBI, CTE, PCS, and PTSD interplay because this issue is a huge piece of the quality-of-life puzzle for me and for them. I know a lot of folks who are still struggling. It feels good to do something about it and know that we can do more than just endure.”

Veterans, even former military service members with asymptomatic exposure to brain trauma or no history of brain trauma at all, can support Project Enlist by pledging to donate their brain like Gowan has. CLF also offers personalized support to veterans fighting the effects of concussions or suspected CTE through the CLF HelpLine.

“Everything we do in the military is about improvement. How do we perform our mission better? How do we make a process more efficient, or safer?” said Gowan. “This mission is an extension of the same mentality. It’s a great opportunity to support veterans when they’re out of uniform and, hopefully, improve life for the generations that come after us.”

Lt. Col. Gowan is a brain pledge and peer mentor for the CLF HelpLine. Gowan spread the word about CLF and Project Enlist with the Institute for Veterans and Military Families (IVMF) in June 2021. Watch the interview here.