The Damage Done

Peter Grant ’83 played interhall football for Notre Dame’s Grace Hall. Dave Duerson, a classmate and casual acquaintance of Grant’s from the dorm, was an All-American defensive back and an 11-year NFL veteran who won two Super Bowl rings. Their athletic careers could not have been more different.

Peter Grant ’83 played interhall football for Notre Dame’s Grace Hall. Dave Duerson, a classmate and casual acquaintance of Grant’s from the dorm, was an All-American defensive back and an 11-year NFL veteran who won two Super Bowl rings. Their athletic careers could not have been more different.

But Grant and Duerson were alike in competitive passion. They played hard. And in the end, the game did not distinguish between them. It turned their intensity into an insidious, mysterious disease. Years removed from their last athletic collisions, they suffered a toll far worse than aching knees or arthritic hips, a loss impossible to repair or replace. They lost themselves and, within days of each other last February, their lives.

Collisions

Spero Karas ’89, the Atlanta Falcons team physician, talks about the intricate, delicate calibration of the brain in a way that suggests he keeps his in fine working order: “Brain cells communicate through ion channels, a normal flux of sodium and potassium and calcium, and then less implicated, of course, magnesium. There’s a fine balance of these as cells communicate with each other in the brain.”

To explain how a high-speed collision can jostle that communication into incoherence, Karas reduces it to a layman’s image: think of the brain at impact, he says, as a racquetball bouncing around a court. “You can imagine those cellular processes going haywire during a blunt-force trauma.”

That’s how someone suffers a concussion. When a collision generates g-forces strong enough to interfere with brain-cell functioning, the immediate effects are familiar: wooziness, confusion, slurred speech. “There’s still no treatment for it, there’s still no medication, there’s still no really firm diagnostic tool,” Karas says. “There’s very much still that we don’t know.”

Doctors do know that a player should never return to competition until the symptoms have subsided and an objective level of neurological functioning has been restored. Computerized testing before an injury occurs, now common at all levels for athletes in high-impact sports, establishes their baseline level of cognitive ability. After a concussion, they must return to that level before receiving clearance to play. This method identifies subtle variations in memory, orientation and reaction time that observation alone might miss, which helps prevent debilitating injuries to vulnerable brains that can occur if players return too soon.

But there’s another hazard, more difficult to identify, and possibly more dangerous: the cumulative effect of hit after hit after hit that never causes a diagnosed concussion. “Linemen might take a thousand, fifteen-hundred hits to the brain every season. That’s the nature of the position,” says neuropsychologist Robert Stern, co-director of Boston University’s Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy — the “brain bank” that investigates trauma-induced disease. “They may not complain of any symptoms, or few symptoms, or irregular symptoms.”

Nothing, in other words, that keeps a player off the field. Yet each collision could be contributing to the development of a degenerative condition with far worse consequences. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) is the contemporary term for the disease forensic pathologist Harrison Stanford Martland identified in 1928 as dementia pugilistica. Punch drunk.

Repeated blows to the head can lead to this mental state that causes symptoms similar to — and, Stern says, often diagnosed as — Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, Lou Gehrig’s disease or the more general term, dementia.

Neuropathologist Ann McKee examines brains donated to the research center, which now has more than 70 from deceased football and hockey players, boxers, and military veterans who experienced combat trauma. On thin slices of the brain stems, McKee identifies the pathology that distinguishes CTE from those comparable diseases. An accumulation of the protein tau inhibits brain-cell function. The condition progresses slowly, but nothing can detect CTE in a living patient. More and more cells die and, depending on the areas of the brain affected, memory loss, mood or behavioral changes offer the first indication of a downward spiral that no treatment can prevent.

A fog

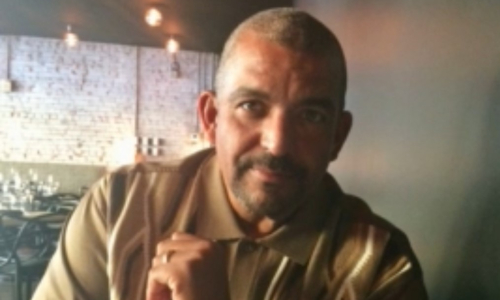

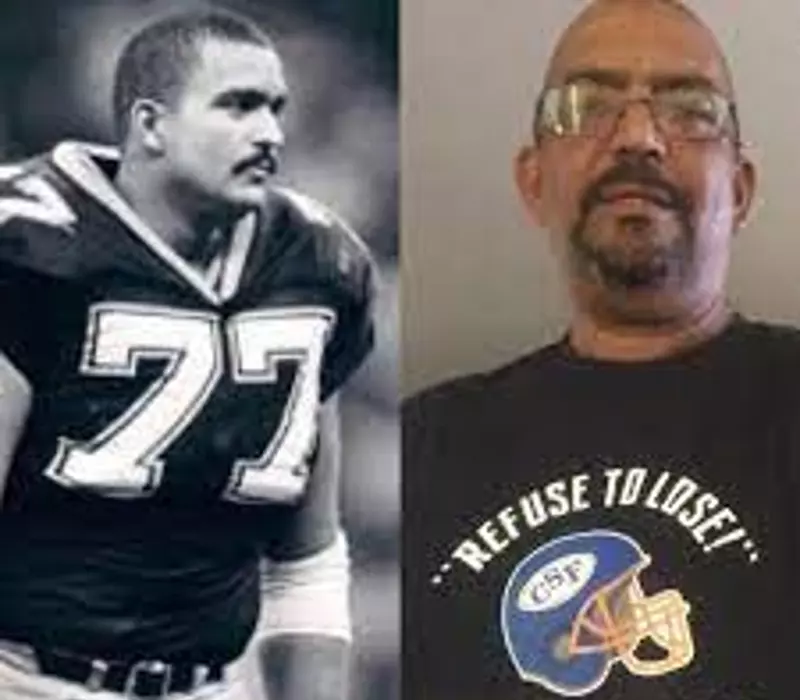

Before she got to know him, Dave Duerson’s future wife, Alicia, feared him. He played with such ferocity that she couldn’t imagine him acting any other way. Their first meeting dispelled that notion, and they stayed together for more than 25 years. “He was so sweet and kind,” Alicia told The New York Times. “He could leave the game on the field and go back to being Dave.”

For more than a decade that included Super Bowl titles with the Chicago Bears and New York Giants, he left the field and went back to being a loving husband and doting father to the couple’s four children. But sometimes just getting home after games was a challenge. In interviews after his death, Alicia recalled driving him because he felt too foggy to be behind the wheel himself.

Tregg Duerson ’08 doesn’t remember much about his father’s “Double D” football persona but recalls him “sleeping like a whole day” to recover from the physical punishment of NFL games. To Dave Duerson, the symptoms — dizziness, nausea, headaches — were routine. With some rest, he was ready to go again.

One report estimated that Duerson suffered 10 concussions, a number that sounds low to Tregg, given his dad’s aggressive reputation and the era when he played. “I think it was a much different culture than today.” And that number doesn’t even account for the untold number of normal hits that he just slept off.

Questions

Repeated blows to the head — whether or not they are severe enough to produce concussions — are a known cause of CTE, but those collisions alone are not enough to trigger the disease. Otherwise every former athlete in a high-impact sport would be debilitated later in life.

A growing body of research, especially the identification of CTE in 14 of the 15 deceased professional football players who donated their brains to Boston University’s study, has stirred public concern. And it’s not just pros, the people who exposed themselves to the risk for decades dating back to youth football. At age 21, University of Pennsylvania defensive end and team captain Owen Thomas committed suicide. His parents donated his brain, which had the telltale buildup of the protein tau associated with CTE. An anonymous, deceased 18-year-old high school football player is the youngest person ever shown to have the disease.

Stern notes that the prevalence of CTE among his center’s subjects reflects, in part, a self-selected group whose mental problems gave them or their families an incentive to seek a posthumous explanation. Still, 14 out of 15 professional football players is a startling statistic, especially for a condition all but absent among the general population. Although the victims have a history of repeated head trauma in common, the underlying susceptibility — why them and not their teammates? — remains a mystery.

“Are some people genetically more prone to developing the disease? Is it things like the age at which someone starts getting their head hit, or the overall duration of the exposure to brain trauma? Or the repetitiveness without rest in between hits?” Stern says. “We just don’t know any of those answers.”

Multiple hits

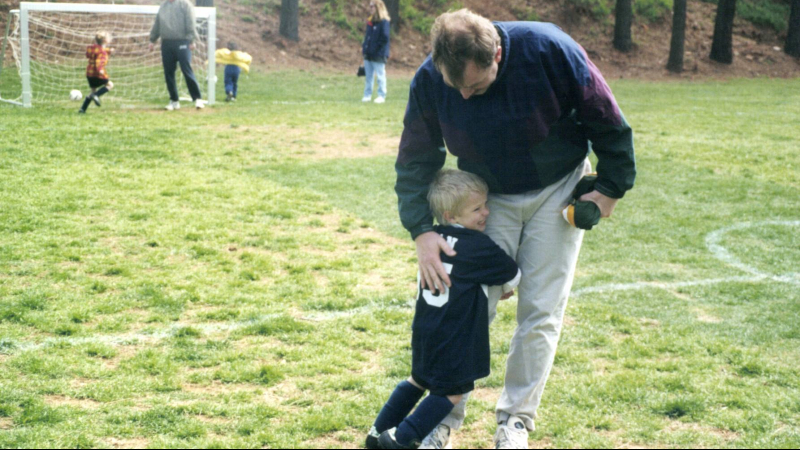

Katie Grant ’11 can only imagine her father as a high school athlete. If Peter Grant played football and hockey anything like he competed against his son, Zachary, “I’m sure he was very intense,” Katie says with a laugh.

He must have been. By his own account, Grant suffered seven concussions, including two that put him in the hospital. Once he was carted off the field, unconscious.

The specifics of the injuries — the circumstances, the severity, the length of recovery — have been lost in the retelling and the vague recollections of family and friends. “We also don’t know,” Katie Grant says, “if he took the full amount of time to heal after them.”

That’s a crucial piece of information. Using an individual’s baseline results, doctors today determine when players can return based on computerized, objective measurements. In the late 1970s, when Grant played high-school sports, identifying how many fingers a trainer held up might have been enough. “Now what’s important is screening, avoiding a second injury to a compromised brain,” Karas says. “That’s where the catastrophic, irreparable damage occurs.”

It’s possible that Peter Grant suffered that kind of irreparable damage before he even graduated from high school.

Long-term fears

Tim Ridder ’99 remembers his concussion and its aftermath the way most people might recall their 4th birthday party. “Remembering,” he says, “is kind of a funny word to throw in there.” From a video of his sideline evaluation and recollections of family and friends — but not from memory — he has cobbled together an account that has become the story.

During a preseason practice as a ND freshman offensive lineman in August 1995, Ridder suffered a concussion on one play and, unaware, returned to the line of scrimmage for the next. After the snap, he never moved from his stance. Assistant coach Joe Moore barreled toward him, raging. But when Moore got there, he found Ridder dazed and in tears, and summoned the doctor.

Longtime Notre Dame sports-medicine specialist Dr. Jim Moriarity went to work, with a camera recording the examination for teaching purposes. In addition to answering Moriarity’s questions, Ridder follows the doctor’s finger with his eyes, touches his nose, and wobbles trying to put one foot in front of the other like a drunk driver failing a field-sobriety test. “I think at that point I told them I had won the Blue-Gold game on my own,” Ridder says, “and I had never even been a part of the Blue-Gold game.”

He hadn’t even officially enrolled as a student. Freshman orientation was the next day, but instead of attending the event, he somehow ended up on the other side of campus, where a friend found him. Over the next week, he called home four times to tell his parents he had suffered a concussion. Not only were they aware of the injury, but Ridder’s father was at the practice when it happened.

Now 34 and a middle-school principal in Leadville, Colorado, Ridder thinks about the potential long-term effects of his “one and only” diagnosed concussion that kept him out about six weeks. All the hits from a football career that included two years in the NFL already reveal their residual aches in his knees and shoulders. He can live with those things. “I don’t want my brain to be the thing that happens early,” Ridder says.

Even that threat — memory loss, dementia, mood or behavioral changes — comes with a sense of culpability. “I did this to my body,” he says. “I had a lot of fun doing it; I knew what I was getting myself into.” Then he reconsiders the thought. “Maybe not completely,” he says, but common sense suggested what science has begun to establish — the correlation between repeated hits and mental decline later in life. Ridder remembers a professor telling him that if men were meant to play football, they wouldn’t have to wear an exoskeleton.

He thought more about the physical consequences then, conscious that his body could absorb only so much punishment without retaliating. That awareness shaped the message he delivered to children about the importance of education: “I’d say, ‘Your body falls apart, but your brain doesn’t. Take care of your brain because that’s what you’ll have going for you long after your body breaks down.’”

Moving forward

After he retired from the NFL, a champion with a charitable heart who had received the league’s Man of the Year award for humanitarian work, Duerson’s professional success shifted to a new arena. His business aspirations were at least as grand as anything he pursued as an athlete — and he paid his dues like a rookie to achieve them. After retiring from football in 1993, he became a McDonald’s franchisee, which requires months of training that includes working in a restaurant. “A year before that, this guy was in the NFL,” Tregg Duerson says. “That’s saying something. He was very hard-working no matter what he did.”

After owning three McDonald’s franchises, he bought a majority stake in meat-supplier Fair Oaks Farms and later started Duerson Foods. He remained involved in NFL labor issues and became a Notre Dame trustee. In business, he was the same ambitious, charismatic success story he had been in football. Even then, whether he recognized it or not, the damage already had been done.

Crash test

Helmets don’t help. Not enough, anyway. Most current models are not designed to protect against concussions at all. They are meant to prevent skull fractures — and they do. “But the head still moves around inside the helmet,” neuropsychologist Stern says, “and the brain, more importantly, still moves around inside the skull. That’s what causes brain trauma.”

A Virginia Tech study — sort of a crash test for football helmets — released a star-rating system in May, the first comprehensive consumer safety information ever published on the industry. As if to illustrate how little had been previously known, the NFL’s most widely used helmet — the league does not mandate what players wear — finished next to last in the study.

There have been improvements. New helmet models absorb more g-forces before they reach the brain; this could reduce the number of concussions. But no current technology can prevent them. Says Stern, “Equipment is not the answer — or it’s not the sole answer.”

As Stern and others continue to pursue research breakthroughs, they know this much: Eventually, some of the people exposed to the thwack of helmet on helmet, over and over again, will get sick. “The key to how to help prevent CTE, or at least decrease the risk,” Stern says, “is to reduce the overall exposure.”

That means less hitting in practice, a precautionary tactic beginning to gain traction. The new NFL collective-bargaining agreement limits contact in offseason workouts and regular-season practices. At the college level, the Ivy League has imposed the most stringent hitting restrictions yet. The rule, implemented this season, allows tackling, or contact of any kind, only twice a week. Current NCAA regulations permit five full-contact practices.

Loving life

There is a history of depression in Peter Grant’s family. In his early 20s, he was diagnosed with bipolar disorder, which he managed for decades with medication. He was open about his condition with his wife and three children, but it was controlled so well that nobody else would have known. “He was always his usual self,” Katie Grant says.

Outgoing and active in his West Bridgewater, Massachusetts, community, Grant chaired the town finance committee, served on the Bridgewater Savings bank board and coached kids’ sports. An accountant with an undergraduate degree in business, he built a career in finance and operations for The Boston Globe and later worked as a media consultant. “He loved his job and the media business in general,” Katie Grant says.

She describes all her father’s interests that way. He loved to talk, he loved to read, he loved to travel. He especially loved Notre Dame. That influenced his daughters. Katie graduated in May and younger sister, Chrissy, is a senior. (Their brother, Zachary, is in high school.) The memory of her dad’s animated campus visits makes Katie laugh. “It was almost too much.”

A sporting chance

Tim Ridder’s torn. He believes safety should be a priority, equipment and medical treatment should be state-of-the-art, and athletes should have as much information as possible about the risks of participation. On the other hand, he loved playing football, and he would hate to see the sport suffer if reasonable precautions could be put in place. “We have to make sure we’re not creating another Rome,” Ridder says, “where there are gladiators dying on the field depending on whether Caesar gives a thumbs-up or thumbs-down.”

Some former players believe that’s how they were treated. Claiming the NFL mishandled concussion treatment and concealed evidence for decades about the long-term effects of head injuries, in July a group of 75 former players sued the league. The NFL vowed to fight the suit, but its approach to head-injury awareness has changed in recent years.

A league medical committee formed in 1994 produced reports downplaying the ramifications of multiple concussions. A 2007 pamphlet informed players that “current research with professional athletes has not shown that having more than one or two concussions leads to permanent problems if each injury is treated properly.”

The message shifted before the 2010 season with locker-room posters describing the threat of depression and dementia, new rules about concussion treatment, and a $1 million donation to the Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy. “It is the hot-button item in the NFL,” Karas says. “It’s probably what we spend the most time on in our disability meetings. What is the NFL but a large corporation that employs thousands of people? And being able to characterize the amount of injury and potential disability and getting these guys back safely is the number-one medical issue in the NFL.”

Duerson’s fall

Duerson understood football-related disability as well as anyone could without medical training. And he knew the horror stories all too well.

Part of a six-member panel that evaluated retired players’ disability claims, Duerson heard about the suicides and the substance abusers. He listened to stories about wild personality changes — violence, irritability, depression.

Duerson could sense himself unraveling in similar ways. At first, he made offhand comments about his brain, expressing concern over symptoms he already felt and fear of how they might progress. His children never knew about those worries. “He was a very prideful man,” says Tregg Duerson, who had never heard of CTE before his father died. “He would not have had that conversation with me.”

But unmistakable changes in personality and judgment altered the course of Duerson’s life. The patient man and prudent executive his family knew began to lash out in profane explosions and make bad business decisions that led Duerson Foods into financial peril. “He always had a very strong temper,” Tregg Duerson says, but in retrospect, he can see how the disease intensified that trait. “I think toward the end of his life, his temper was more quick — he was easily agitated.”

Duerson’s personal problems splashed into the newspapers in 2005, when he was arrested after pushing Alicia against a wall at the Morris Inn on the University campus. He pleaded no contest, resigned from the Notre Dame board, and soon he and his wife were divorced. Everything seemed to be falling apart because his personality had changed in cataclysmic ways that he feared with chilling prescience.

Mental collapse

In December 2009 something changed. Medication that had controlled Peter Grant’s mental illness for more than two decades stopped working. He became lethargic and withdrawn. Depressed.

Grant’s doctors adjusted the dosages, to no avail, and searched in vain to explain alarming mood changes. Home for Christmas that December, when her father’s new symptoms surfaced, Katie Grant thought he was preoccupied with work. When he visited Notre Dame two months later for Junior Parents Weekend, she recognized the depth of his depression.

His usual enthusiasm for a trip to South Bend vanished. “He just sat in the hotel room, didn’t want to do anything, didn’t even want to walk around campus,” Katie says. “It was a 180-degree transformation from anything I had ever seen.”

Through the summer and into the fall of 2010, it got worse, still without explanation. He had manic episodes — not sleeping, running around, talking incoherently. “Really sort of out of his mind,” Katie says. One episode in October left him hospitalized for two weeks. After his release, he remained unstable. Alternately manic and depressed, Grant would claim to be feeling all right on his better days, “but it was a lot worse than he was letting us know.”

There was no violence or anger, just withdrawal and forgetfulness. A dinner conversation would disappear in the fog of his mind, and when the subject came up again a day or two later, he would be upset that he hadn’t been told about it before.

That change was especially jarring for Grant’s family, who counted his intelligence and sharp attentiveness among his most notable characteristics. He was always on top of things. The difference could not have been lost on Grant himself, either, and they imagine that the frustration of his prolonged mental descent took an untold toll.

“I definitely think he felt hopeless,” Katie says, “that he just wasn’t going to get better.”

Duerson felt the same way. His financial problems reached their nadir in 2010, when he filed for bankruptcy and Alicia sued to collect unpaid child support, seeking assets that included his NFL Man of the Year award. By then he lived in Sunny Isles Beach, Florida, a family vacation destination where he moved full-time. In retrospect, he might have moved there to retreat from life as he felt his ebbing. Duerson’s friend Ray Ellis told the Miami New Times, “He didn’t want to crumble in front of an audience.”

Legacy

On February 8, Peter Grant committed suicide. Nine days later, Dave Duerson shot himself in the chest, a report that reverberated around the country because of the reason he did it that way: to preserve his brain for CTE research.

Both the Grant and Duerson families donated the brains. Grant’s showed a mild level of CTE, Duerson’s much more advanced. Announcing the findings in Duerson’s case, the neuropathologist McKee displayed slides showing extensive damage to areas that affect “judgment, inhibition, impulse control, mood and memory.”

There’s solace in the CTE diagnosis for both families, insight into the torment that led Grant and Duerson to take their own lives. Beyond the emotional comfort, Stern says, their donations establish a legacy of medical evidence that transcends their own tragedies. Uncertainty still surrounds the disease. Players are left to wonder whether they will suffer a similar fate, or if hints hidden in the brains of previous victims will reduce the impact.

Jason Kelly, a former sports columnist for the South Bend Tribune, is an associate editor of the University of Chicago Magazine. His most recent book is Shelby’s Folly: Jack Dempsey, Doc Kearns, and the Shakedown of a Montana Boomtown. Email him at [email protected].

Peter Grant ’83 played interhall football for Notre Dame’s Grace Hall. Dave Duerson, a classmate and casual acquaintance of Grant’s from the dorm, was an All-American defensive back and an 11-year NFL veteran who won two Super Bowl rings. Their athletic careers could not have been more different.

Peter Grant ’83 played interhall football for Notre Dame’s Grace Hall. Dave Duerson, a classmate and casual acquaintance of Grant’s from the dorm, was an All-American defensive back and an 11-year NFL veteran who won two Super Bowl rings. Their athletic careers could not have been more different.

Jesuit High Schools Jacob Hall has had numerous injuries that have sidelined him at the end of his high school football career. His father, Jesuit teacher and coach Justin Hall, suffered from chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE, caused by concussions during his football career which including college at Notre Dame. The neurodegenerative disease culminated in his suicide four years ago. Moments before their game against Vista del Lago on Saturday, April 17, 2021, Jake shows a table that honors his father on campus at Jesuit High School in Carmichael. Xavier Mascareñas

Jesuit High Schools Jacob Hall has had numerous injuries that have sidelined him at the end of his high school football career. His father, Jesuit teacher and coach Justin Hall, suffered from chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE, caused by concussions during his football career which including college at Notre Dame. The neurodegenerative disease culminated in his suicide four years ago. Moments before their game against Vista del Lago on Saturday, April 17, 2021, Jake shows a table that honors his father on campus at Jesuit High School in Carmichael. Xavier Mascareñas