Warning: This story contains mentions of suicide that may be triggering to some readers.

From Nate’s father:

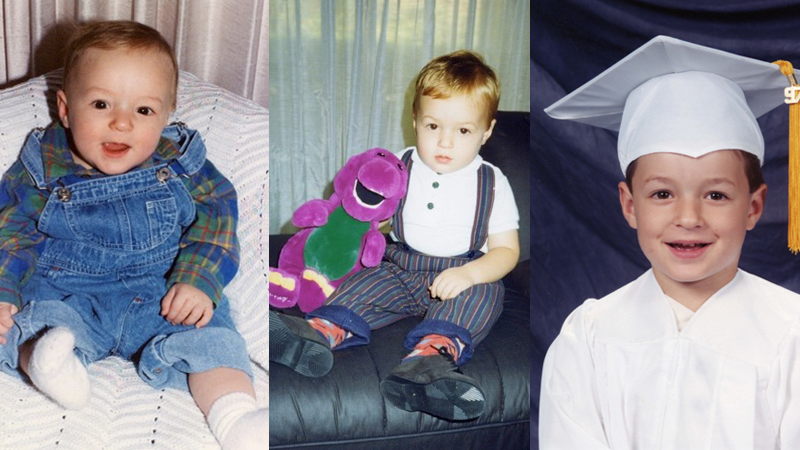

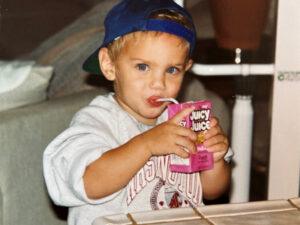

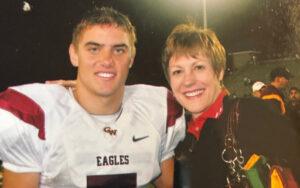

Nathan James Fellner was born on April 22, 1991, the happiest baby you could ever have known. He was constantly laughing and giggling, a total ball of energy. Nate never slept, literally. That energy translated into a gifted athlete with a sense of humor from the time he was a toddler.

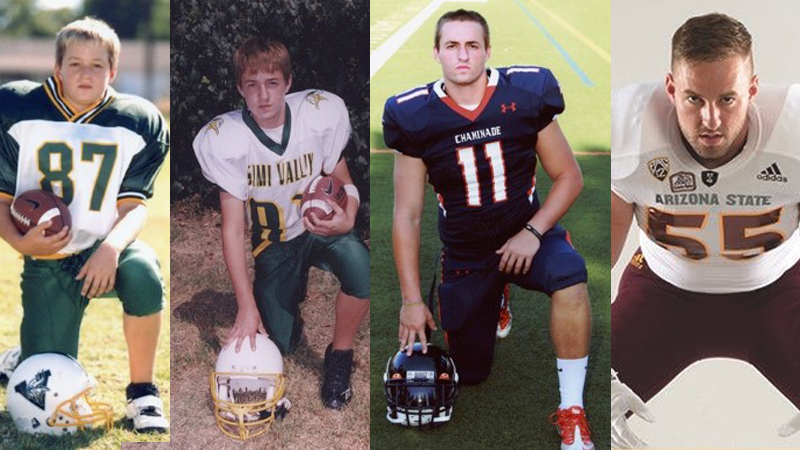

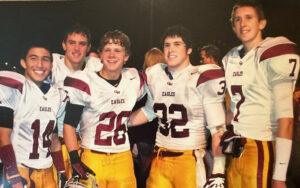

Nate shined in every sport he tried: tee-ball, soccer, baseball, track, wrestling, and especially football. From a young age, he’d watch college football with me and say, “I want to do that, dad.” We discussed ways to reach his goals, and he set his mind to them. He wanted to excel in the classroom, in the community, and on the field. Play hard and keep your head down, do good things, help others, live up to your word, and be honest with what you say and do.

When Nate was little, his family called him “Nate the Great” because of his ability to stand out in everything he did. He wasn’t fond of that nickname as he thought it was egotistical, but it stuck nonetheless. Growing up, his friends called him “Nate Dawg” for his dogged determination and drive.

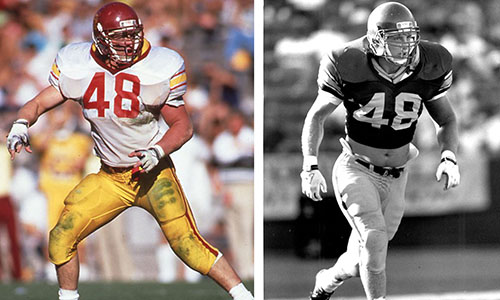

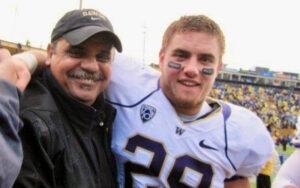

As a starter at Clovis West High School, Nate accomplished so many of his football dreams. He was an intricate part of the Valley Championship winning team, earning scholarship offers to many Division I schools including Stanford, Arizona, Washington, and the Air Force Academy to name a few. Ultimately, he chose to play for the University of Washington Huskies throughout his college career.

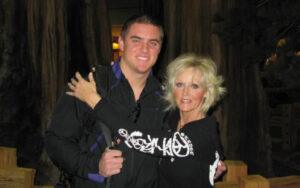

Nate struggled with demons and managed them as best he could. He was a Christian who strived to find answers with the help of God’s Word, which we discussed often in the later part of his life. I believe he was on the right path when he left us. I know in my heart he is finally resting in peace with Our Father.

I will see him again someday, God willing. Loving and missing you always, Nate.

The Nathan Fellner Memorial Scholarship

We created the Nathan Fellner Memorial Scholarship fund to honor Nate’s memory and bring awareness to the academic, athletic, and mental health issues student-athletes often face. This scholarship recognizes and supports students who will continue their formal education upon graduation from Clovis West, and who exhibit a strong character, perseverance through life’s challenges, and a distinctly brilliant sense of humor and competitive desire – all of which made Nate an exceptional friend, student, and athlete.

From Mikayla Pierce, Nate’s childhood friend

I had the pleasure of knowing Nate since I was five years old. Elementary school days turned into Kastner intermediate school days, and then four years of cheering for Nate on and off the field at Clovis West. Our twenties were spent seeing each other at holiday breaks as permitted by his football schedule.

The boy had a knack for making me laugh until my stomach hurt, and he had the same effect on everyone around him. Nate also had a sincere and thoughtful side – checking in on friends and making sure they were alright. My hope is that everyone saw him more for his heart and playful personality, not just the football phenom he was on the field.

Nate is now free of pain. The donation of his brain is a huge step in the right direction. I hope the study and CTE diagnosis of not only his brain but others like his forces organized sports to see how much more must be done to protect the health of their athletes.

I am so honored to have had Nate as a close friend for as long as I did. What a presence he had, and such a large void he has left among us.

From Anthony Elliott, Nate’s childhood friend

In the 30 years Nate was in my life, there are two qualities I most admired and will always remember. One was his sense of humor, and the other was his love (and talent) for all things athletic. Our friendship revolved around both.

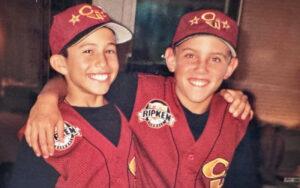

Starting in kindergarten, Nate was the class clown and could make anyone laugh. Every day, we would head to recess for an intense game of basketball or football. Nate was fast, had a rocket arm, and could catch anything. During our summers, we also played baseball together and he was just as good there. Next came soccer, cross country, track, wrestling, and any other sport our schools offered. And you guessed it, he was good at every. Single. One!

From early childhood to our late teens, Nate and I were basically inseparable. Along with our other friend Ethan, the three of us spent over a decade seeing each other every single day. These are memories and stories I will cherish for a lifetime. Some were the best moments of my life.

Once we turned 18, we moved to different cities but that never stopped us from being in constant contact. Technology allowed our friendship to continue like it always had, spending our days texting each other jokes and sports updates. We talked about working out and training as if we still had games on Saturdays. Not a day goes by that something small – a song, an exercise, or a football team or player, doesn’t remind me of Nate. I miss him, and even writing this brought smiles and teary eyes.

Finding out about Nate’s CTE diagnosis came with mixed feelings. On one side, it brought some closure to have an answer for some of the battles Nate was fighting. He had his ups and downs, and his lows were hard on everyone. The other part of me was just heartbroken. This sport that we grew up with, loved, and helped shape us, ultimately led to Nate’s struggles. Hopefully his diagnosis can help prevent the same from happening to others in the future.

Nate’s friendship was one of the biggest blessings in my life. I love and miss him every day, and hope that we can make his name live on.

_____________________________

Suicide is preventable and help is available. If you are concerned that someone in your life may be suicidal, the five #BeThe1To steps are simple actions anyone can take to help someone in crisis. If you are struggling to cope and would like some emotional support, call the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline at 988 to connect with a trained counselor. It’s free, confidential, and available to everyone in the United States. You do not have to be suicidal to call.

Are you or someone you know struggling with lingering concussion symptoms? We support patients and families through the CLF HelpLine, providing personalized help to those struggling with the outcomes of brain injury. Submit your request today and a dedicated member of the Concussion Legacy Foundation team will be happy to assist you.