John Pell

John Pell grew up in Pahokee, FL, back in the 1950s. He went to school barefoot with the hem of his jeans rolled. Every day, he milked the cow and chopped firewood, taking turns with his brothers, before breakfast and dinner. John was full of fun. One day while his mother hosted bridge club, he quietly brought his goat Gruffo around to surprise everyone. He gave nicknames to all six of his siblings, the best of which went to his baby sister, Kathy, born in the 60s—The Punk!

John loved football, rightly so, as his father was the football coach and athletic director. Pahokee didn’t have little league football, but he got plenty of experience playing with friends in the park and joining the junior high school team. As John was small, he stayed back a year in the seventh grade to give him a little growth advantage. In high school, John played quarterback. Football was so rough against rival teams that he finished more than one game with a clawed face and vomiting until he had to go to the emergency room.

While at Pahokee Junior-Senior High School, John took part in many sports. Although mostly known for football, he was great at basketball too. A teammate once said John’s set shot was a performance, practiced to perfection. John would sink down, knees bent, ball in front of his nose, and then explode upward in one fluid motion, hands splayed over his head like butterfly wings. The ball would sail towards the rafters, and of course would go in, usually all net. It was always quite a show.

Along with sports, John was an avid boy scout who went on incredible camping and fishing trips. He also worked on weekends and holidays with a local carpenter through high school and college breaks.

John played defensive back at Northeastern Oklahoma A&M (NEO). He received All-American Honors while at NEO and still holds a record of 18 interceptions in 20 games from 1966-1967. He went on to play at Florida State (FSU) as a cornerback. His teammates awarded him the Page trophy for his personifying spirit of Michael Page. John was noted for his tremendous speed, courage, and pinpoint passing. In 1968, he participated in the first annual Peach Bowl. He graduated with a Bachelor of Science degree in 1971.

For a short time after college, John went on to play professional and semi-pro football in Canada with the Ottawa Rough Riders and Orlando Panthers. He remained small (6’1” and 183 lbs.) and by the end of his career, had suffered at least 31 concussions he could recall. His worst concussion was at NEO during practice. A teammate knocked him out cold, and he woke up 30 minutes later on the locker room shower floor.

John started his career in the Florida Keys teaching industrial arts and coaching at Plantation Key High School. Before long, he found real estate more lucrative. He became a real estate broker, opening his own firm and turning it into a successful business. He earned two Commercial-Investment Real Estate Council Certificates, one for “Fundamentals of Real Estate Investment and Taxation” and the other for “Fundamentals of Location and Market Analysis.”

His work attire consisted of tennis shorts and shoes. The nearby Cheeca Lodge called John anytime they had a guest looking for a tennis partner. He loved the game and played anytime he wasn’t working or on the beautiful blue water. While crossing the bridge near his office, he once told his son, Clay, “Roll down your window. Take a good look. Always remember, THIS IS LIVING!”

He loved being a father and grandfather. His children, Johnna Juarez, Clay Pell, and John David Pell, found him to be a great mentor, giving them sound and unbiased advice—always there to listen. He encouraged sports and attended as many of his children’s games as possible. His sense of humor transferred through the family. The grandkids called him “Geez”, short for old geezer. When he phoned the kids, he always announced, “It’s the Old Man.”

After many good years in real estate, he and his wife Roseanne moved to Okeechobee, Florida, to be closer to his aging parents. John and Rosanne built a home on beautiful, wooded-acreage in Bassinger, north of Okeechobee. He continued selling real estate and playing tennis while raising a few cows and riding his beloved cracker horses.

Around the age of 66, John began noticing a physical change. Three years later, he was diagnosed with Neocortical Lewy Body Disease. John’s walk became a shuffle, his dexterity and cognitive functions worsened, and hallucinations began. He had panic attacks, but with an antidepressant was able to control his anxiety. Mentally, he was declining and needing more care. John started having seizures which caused many falls and debilitated him. After a brief hospitalization, he went to a rehab facility. His seizures were more frequent, he was not cognitive, and lost his appetite. Less than two months later, John passed away at the age of 75.

John’s wish was to donate his brain to the UNITE Brain Bank. Upon study, researchers found many medical conditions, including:

Stage 3 (of 4) Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE)

Neocortical Lewy Body Disease

Limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy (LATE), Stage 2

Vascular disease

While John had many reasons to complain, he never did. He remained a loving, caring husband, father, and brother to the end. John was honorable and trustworthy in his personal and business life. His gentleness, kindness, and humor were evident even in the hospital and rehab.

His injuries never dampened his spirit and love of football. He believed football taught him the importance of team building, tenacity, and to always give your best.

The Pell family feels blessed to have had the opportunity to work with the wonderful staff at the Concussion Legacy Foundation and cannot thank them enough for all their help.

Toby Brundage III

Toby devoted much of his college time and energy to playing football. As All-Ivy center he was a “Beast” on the field and a Teddy Bear all other times. While at Harvard he was named to the Epson Ivy Bowl team where Ivy-league all-stars compete against top Japanese players. He loved getting together with his Harvard friends and teammates and appreciated Coach Joe Restic’s philosophy: “to make gentlemen and good men out of his players.” Toby’s teammates awarded him the Joseph E. Wolf Award. Toby is a 1991 graduate of St. Thomas Aquinas High School in Fort Lauderdale, FL, graduating with honors. Toby’s essence was charm, integrity and kindness; he was always ready to treat his friends and family and take care of others. His smile and wit would light up a room. Family and traditions were important to him as seen in his close relationship with his Nana who lovingly shared her stories of yesteryear and her famous home-baked goodies. Together they shower us with their devoted love from above. He was a longtime member of the Lago Mar Country Club in Plantation, FL where he honed his golf skills to a 3 handicap. He also appreciated and collected fine cars and participated in the sport of car racing.

After his death, Toby’s brain was studied at the UNITE Brain Bank. Researchers there diagnosed him with Stage 2 (of 4) Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE).

Ray Perkins

Ron Perryman

Morris Phipps

His family said he was the child that was always outside playing a game that involved a ball. Football was his passion but he was also very gifted in baseball. He played his high school football and baseball for the South Garland Owls, where he made All-State in football and played in the All Star Game for the North All Stars. He had offers to play both football and baseball in college, but made his choice to play for Baylor University beginning in 1965 through 1970.

Morris Trent Phipps was the eldest child born to Morris Lynn Phipps and Billie Rae Phipps. His family and friends all called him by his middle name, Trent. He had two younger sisters.

His family said he was the child that was always outside playing a game that involved a ball. Football was his passion but he was also very gifted in baseball. He played his high school football and baseball for the South Garland Owls, where he made All-State in football and played in the All Star Game for the North All Stars. He had offers to play both football and baseball in college, but made his choice to play for Baylor University beginning in 1965 through 1970.

At Baylor, Trent played on the defensive line as nose guard. The coaches thought he was too small but his tenacity, quickness, and strength always earned him his starting position. He loved strength training and his past time was handball. He graduated in 1971 with a Bachelor’s degree in Physical Education/History. He was the first in his family to ever attend or graduate from college.

In 1971, he married Donna Clark Phipps during her sophomore year at Baylor. They moved to Lubbock where Donna could finish her degree to be a speech pathologist and Trent began his coaching career at Lubbock Cooper High School. Trent and Donna have two sons: Brett, who coaches in the Dallas area, and Garrett, who has a dental practice in Guymon, Oklahoma.

Trent and Donna had the typical coaching moves around Texas to find that “greener pasture” where the athletes had the perfect combination of skills and motivation. Trent coached at Lubbock Cooper High School, Lubbock High School, Sweetwater High School, Graham High School, and Uvalde High School. While in Uvalde, Trent completed a Master’s in Administration. He was a principal for one year in Van Horn, Texas, and felt his glory days still called him to coach. In 1986, the family moved to Amarillo, Texas. While in Amarillo, Trent coached at Tascosa High School, Bonham Middle School, Palo Duro High School, and Horace Mann Middle School. He retired from coaching and teaching in 2003.

In hindsight, Trent was beginning to show the effects of CTE as early as 1997. His diminished cognitive skills and depression were such that Donna took Trent to seek answers in late 2002. His diagnoses ranged from sleep apnea to serious depression to Early Onset Alzheimer’s disease and his final diagnosis from post mortem autopsy was primary Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy.

Trent’s family misses him greatly but would want you to know the devastation of this disease and ask you to support, in whatever fashion, the research that may some day prevent others from suffering the effects of CTE.

Given with great love for father, husband, teacher, and coach, Morris Trent Phipps by his wife, Donna, and sons, Brett and Garrett.

Richard Pickens

My father was a strong physical presence. He was shorter, but thick and muscular. My body tends to reflect his. My older sister and my childhood was filled with waterskiing, fishing, tubing, and attending University of Tennessee football games. As a young soccer player, I would challenge my father to races next to our grandmother’s garden, on a football field, from one tree to the next, and he would always make sure he won. He was a football prodigy in his hometown of Knoxville, Tennessee, where football was king. He played high school ball at Young High School and had an outstanding career with the beloved Tennessee Volunteers, coached by Doug Dickey. Wearing #34, he played in the ‘66 Gator Bowl, ’67 Orange Bowl, and ’68 Cotton Bowl, and won the All-SEC Fullback of the Year award in 1968. After his career at UT, he made the preseason team for the Houston Oilers and was later inducted into the Tennessee Sports Hall of Fame.

Dig deeper, though and there is an uglier, more painful layer to my father’s story. His time with the Oilers ended after he lost his temper with his coaches. He exhibited tantrums on the sidelines of my college soccer games at referees or players, which always embarrassed me.

In our personal lives, while our childhoods had glimpses of happiness with our father, cracking jokes over “RC Colas and moon pies,” using his video camera to make our own fishing shows, and eating his famous steak and mushrooms, we were always nervously anticipating the next violent episode. We closed our eyes and held tight while he drove recklessly with us in the car. We locked ourselves in bathrooms, or frantically packed our things to jump in the car and drive away. We never knew when he would erupt.

When we were old enough to understand, and long after our parents divorced, we attached this behavior to his alcoholism and anger management issues. We later realized, though, there were confounding issues.

My dad’s playing career included close to 200 concussions by his estimation. After his death in July, 2014, we donated his brain to the UNITE Brain Bank, where scientists confirmed primary diagnoses of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) and motor neuron disease associated with CTE. His substance abuse was a contributing diagnosis.

The symptoms of CTE can be expressed erratically, including violence, mania, depression, dementia, among others. Once a physical presence, my father was reduced to stumbling across the room, shuffling his feet and holding onto furniture because he was too stubborn and proud to use a walker. He liked to refer to his debilitation as a “hitch in his giddup.” In addition to his outbursts and aggressive behavior, he developed difficulty with concentration and organization in his 30s. By his 50s, he suffered from language difficulty, weakness in his legs, and progressive decline in his behavioral, cognitive, and motor functions. He was misdiagnosed with Lou Gehrig’s Disease, to which my sister organized a team in his honor for an ALS walk. The diagnosis, for a variety of reasons, didn’t quite fit, and was changed to Primary lateral sclerosis (PLS). Once again, he was misdiagnosed. He was losing his mental and physical capacity, and he didn’t know why.

As his symptoms progressed, the glimpses of happiness we once saw of our father in childhood lessened. We knew our visits with our father must not exceed 36 hours, or we would tumble into dark topics of despair. We brought lists of uplifting topics and stories to share, my sister playing the soothing, empathetic nurse, and I would operate as the ultimate jokester. Once, as a 20-something, I broke our golden rule and extended beyond a 36-hour visit. He attempted to physically attack me, but I was fresh out of college and fast as hell. He was reduced to holding onto furniture, shuffling his legs, lest he might fall. From that moment on, I broke communication with my father.

My sister and mom gave me updates on his condition from then on. He moved into a nursing home after totaling his car. He showed Sundowning behavior often, and his drinking contributed to him dying, with lots of life to live, at age 67.

In his nursing home room there was a display case with one of his Vol helmets, boasting a deep crease from a violent collision at Neyland stadium. My father’s football friends rallied around him, taking care of him, his finances, and his funeral, as he refused our help. Even though we now know his football career caused him so much pain, my father requested for his football friends to spread his ashes where he once played the game he loved.

I share this version of the story to shed light on the very real narrative of a man whose life was stolen by the decay of his brain. While parents continue to send their children out on the field in helmets and pads and memorize stats to draft their favorite players to their fantasy team, I believe CTE becomes something easier to ignore than to recognize. CTE is a hindrance to our culture’s Saturday and Sunday (and Monday and Thursday) pastime. This year marks the fifth anniversary of my father’s death, and I am at peace with the chaos and destruction my father caused on our lives. I am beginning to fondly remember the happy times with my father when he was free from the hold of his confounding diseases. And I am hopeful for continued progress on the efforts to combat the fatal impact of CTE.

Greg Ploetz

Gregory Paul Ploetz was a Renaissance Man. He was brilliant, clever, and could do most anything. He was not only a gifted teacher and artist, an educated speaker, but he could also change the oil in his car and plumb and wire an entire house.

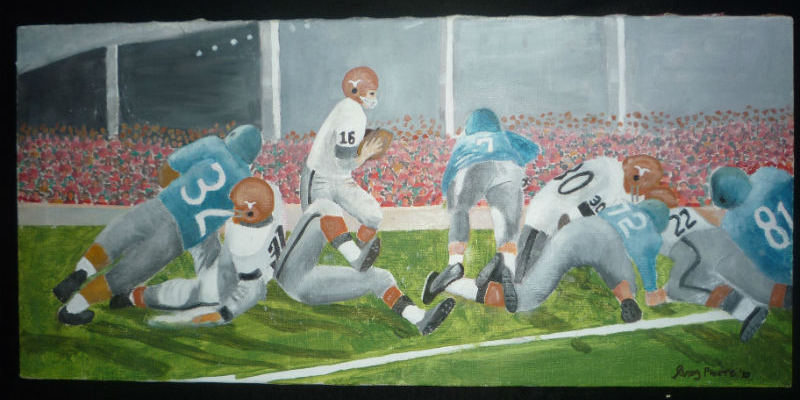

His success as an athlete was proven by his participation on the 1969 University of Texas National Championship Team. He was a formidable Defensive Tackle and was elected to the All Southwest Conference team twice and 2nd team All-American. Unfortunately, this success caused him to suffer and die from Stage Four CTE after battling the disease for more than ten years. He had no other health issues.

Greg and I were married for 37 years after only dating for five months. It was love/like after the first date. He had his Masters of Fine Arts from the University of Texas and used his talent for sharing his knowledge of art through teaching at the college and high school levels for forty years. He was also a committed and loving father of our two children. We were going to spend our golden years owning and living in an art space/gallery in San Antonio, TX near his family. CTE robbed Greg of fulfilling his dream.

In 2009/2010 the neurological community did not feel comfortable calling it CTE before death and three neurologists kept telling us it was Alzheimer’s. CTE causes dementia, thus, it is the only dementia that is preventable. For Greg, using medical marijuana the last two years of his life helped diminish his suffering and gave him some peace of mind. In 2014, we moved to Colorado, and got him a license to use the oil. I stopped all of his prescribed behavioral drugs and used MMJ.

If he knew he was going to die from this disease, I think he would have chosen not to play. He ended up loving art over football. During his art career he was mostly an abstract painter, but in 2010, with full blown dementia, he tried to execute the realist art form in a naïve football painting. It was one of his last attempts to make art.

Like others that have lost a loved one, my grief and pain is with me every day. It gives me comfort to share his art and journey. He has a very important legacy and story to tell.

Greg’s niece, Meg Dudley, directed and produced a short film, “Art of Darkness: A Story of CTE,” capturing his decline and its effect on his family. View the film below.

Greg’s work was featured in an art exhibit at Fort Works Art in Fort Worth, TX in September 2017. A portion of the proceeds benefitted the Concussion Legacy Foundation.

John Polonchek

Jim Proebstle, Author of Unintended Impact, sat down with the family of John Polonchek to gain insight into his life and legacy.

Jim Proebstle, Author of Unintended Impact, sat down with the family of John Polonchek to gain insight into his life and legacy.

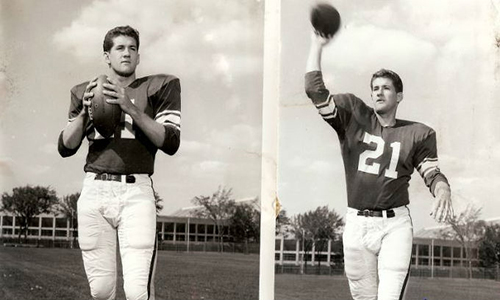

John immigrated to the United States from Granastov, Czechoslovakia with his family when he was a young boy. As he grew older it was his love for sports of any kind that helped him become a part of the American culture. That story built momentum with his talent as a halfback at Roosevelt H.S. in E. Chicago, IN, which led to a scholarship at Michigan State University. At Michigan State John was the first recipient of the Potsy Ross Award, an honor given to the football player making the most contributions to the team on the field, as well as in the classroom. After graduation, John joined the Air Force and after serving he returned to MSU to begin his coaching career. His talent for the coaching profession can only be properly described by a Google search that documents six years of college coaching and twenty-eight years of coaching in the NFL, AFL, and USFL (United States Football League), including coaching two teams in the Super Bowl (the Raiders in Super Bowl 2, and the Patriots in Super Bowl 20). His athletic talents and native intelligence gave John the opportunity to earn a college degree. Football was part of his essence and being, allowing John to build a career that was characterized by success at all levels and a lifestyle centered on his family and the sport. That passion for football and coaching came full cycle with the donation of his brain to the Boston University School of Medicine CTE Center after a bittersweet end when he passed away on January 26, 2015. It is his family’s intention that John’s contribution to football continue through the use of his brain in researching the long-term consequences of repetitive head impact through concussions.

Who was your dad outside football?

Joan, John’s wife of sixty-eight years, and he met while in the Air Force where she was an Air Force nurse. Afterwards, she quickly adjusted to his hard working life style of full-time coaching. Regardless of the time demands, he maintained his commitment to his faith, his friends and his family. His children describe their dad as gentle, friendly, quiet and humble. “He always wanted to know what he could do for us. It was never about dad’s accomplishments, but always about others.”

How did the topic of concussions and head contact come up during John’s coaching years?

The family looks back at the environment involving concussions as very different than what we think of today. “The topic of concussions didn’t come up,” Joan said although later expressed concern for the players and the possible long-term consequences of head trauma. Professional football bred a “tough as nails” attitude, which included a culture that concussions were part of the atmosphere, part of the expectations of the sport, especially during the early years of building a new league (AFL) without the big money. The evolution of equipment was thought to be of great benefit to the players as the physics (player size and speed) of the game changed. That idea was turned on its head with the Darryl Stingley/Jack Tatum collision at the Oakland Coliseum in 1978. Although controversial, the hit on Stingley, one of John’s players with the Patriots, was not against NFL rules at the time, as it was not helmet-to-helmet contact (it was a shoulder-to-helmet contact). No penalty was called on the play. Today, however, the NFL has banned all blows to the head or neck of a defenseless player, and has disallowed players to launch themselves in tackling defenseless players. With Darryl reduced to life as a paraplegic, the team was spooked. While concussion and head trauma protocols have improved none of the family members believe that the issue of player safety has been resolved.

In retrospect, there is no one incident that the family could recall that represented a marked change in John’s behavior. He just gradually withdrew into himself. The mental and cognitive preparation for the season was more time consuming resulting in several occasions where John spent the entire night preparing for the next day’s practices and upcoming games. After the end of the 1991 football season, he retired.

When did you notice that something was wrong with John? How did the symptoms progress?

During a family celebration in 1998 at an airport, the kids had engaged the parents in a clapping-coordination game requiring dexterity of hand movements. John had always been “mister motor skills” but he couldn’t keep up with the pattern of the game. His family noticed that John began to speak less frequently and was less involved in conversations when in a group, and that his prolific photographic skill just stopped. Problems with confusion led to a visit at Mass General in early 2000 with the preliminary diagnosis being a likely beginning stage of Alzheimer’s. The family never quite accepted that diagnosis. John never became aggressive and his personality stayed the same. Word search skills became challenging and daily living issues started to become evident. In time, more progressive signs presented themselves as he just talked less and less. He would just sit in a chair and watch football or any sport on TV for long periods of time. His memory declined to include a loss of recall of events that were very important to him. He was very happy to receive visitors while at the nursing home, but had no recall of who they were.

It was not a surprise to the family that when John’s brain was examined by Dr. Ann McKee there was no evidence of Amyloid protein stains typical of Alzheimer disease. There is satisfaction among family members that a correct diagnosis of CTE was determined so that a validation of the signs and symptoms they were seeing may lead to answers from a scientific standpoint so that others can benefit.

How has your attitude changed regarding football?

The family expressed concern about what’s happening to the player’s bodies. With the competitive culture of the professional game, “It’s just going to get worse.” Research, rule changes, precaution through better officiating are long overdue, but changes are not happening fast enough. “If we can put people into space and protect racecar drivers in collisions; why can’t we develop equipment to protect our players better. We have a long way to go. And, the issue is compounded further when you consider the players at the college, high school and youth levels. Flag football might be a much better alternative until a later age. Some of the hits are gut retching and make you cringe. Risk factors are increasing and we have a long way to go to make the game safer for players.”

How was your experience working with Concussion Legacy Foundation (CLF) and Boston Medical?

“Fantastic, available, helpful,” were the first words Joan used to describe the Concussion Legacy Foundation. “Lisa was indispensable in coordinating research with everyone in different places. The medical staff are world-class and the CLF programs going forward are terrific. It was motivating, interesting, and meaningful to participate in the leading edge science involved. We are hopeful that a difference can be made in player safety as the game of football evolves.”

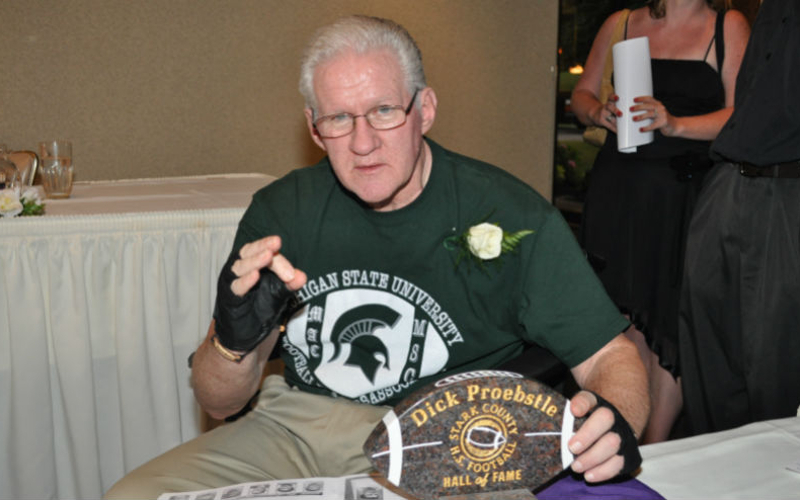

Dick Proebstle

Richard James Proebstle Eulogy

I am honored greatly to be able to express myself with you on behalf of my brother, Dick. But first, I would like to thank each of you for your presence here and the wonderful compassion and kindnesses in your cards, emails and phone calls to the family. They really did make a difference.

In 2005, Steven Jobs addressed the Stanford University graduation class and in his commencement address he was quoted as saying, “No one wants to die. Even people who want to go to heaven don’t want to die to get there.” He expanded the point by saying, “Death is very likely the single best invention of Life. It is Life’s change agent. In his conclusion he said, ”Remembering that you are going to die is the best way I know to avoid the trap of thinking you have something to lose. You are already naked. There is no reason not to follow your heart.”

I started thinking about this more. While the physical and metaphysical changes for Dick are self apparent, changes that came as a byproduct of his death became interesting. I’d like to mention a few:

- Mike and Patty and Carole and I were privileged to tag team what turned out to be a week-long vigil with Dick. During that time it became very apparent as to how much Mike and Patty had grown into their responsibilities in managing the complication of Dick’s affairs over the last few years—right through until today when we say farewell. They loved their father very much as he loved them.

- I changed because Dick’s situation gave me an opportunity over the last few years to give back to a brother who gave so much to me. Our connection at all stages in life was very strong. It was Carole, however, who noticed that despite my changes, Dick and I had grown to look more and more alike. She came into Dick’s room at the Peabody the night before he died. I was asleep on a recliner chair next to Dick’s bed. My head was back, mouth open, breathing heavily; just as Dick’s was. Carole laughed out loud with how much we looked alike and nearly put a Post-it note on my forehead saying, “This is the visiting brother…do not medicate.”

- Dick was a challenging resident in the beginning at The Peabody. I saw their staff change over time, however, and continually make the second effort in order to make Dick feel at home. It was heartwarming to hear their stories while we were there as to how Dick had become part of their family.

- Some of you know that Dick’s brain has been donated to Boston University where leading research is being conducted into Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy or CTE dementia. It’s a growing concern for players receiving repetitive head concussions in contact sports and can only be diagnosed post-mortem. Isn’t this just classic Dick Proebstle overachievement. His greatest contribution in sports may be yet to come…after his death. Hopefully, it will facilitate change.

- Throughout the process of Dick’s death, family and friends, like yourselves, made comments that aren’t a normal part of day-to-day living. Sometimes these acts of love and compassion go unsaid in our lives, but not this time. I was particularly comforted by everyone in my immediate family and in particular by a voice mail message from my son, Jeff, which I will probably never erase.

- Lastly when considering these changes and I’m sure there are many others, the ultimate question arises…Are we really going to change? Will we actually become better as a result of reflecting on the experiences of the death of someone we love?

As a brother, I look at Dick’s role in life as a Warrior…”a man of honor experienced in the battle and willing to lead and take on the fight.” Positive characteristics for a Warrior include: competitiveness, achievement driven, leader, high personal code, etc. These all leave us with very big shoes to fill. I know first-hand from St. Joan of Arc, Central Catholic and Michigan State just how big those shoes were. But, just as there are strengths to being a Warrior, there are also weaknesses; ego driven, hard on relationships, inflexible and self-destructiveness to name a few.

Carole has a saying in her psychology practice that, “Life is all about learning.” With that thought in mind, Dick got a Ph.D in life. His amazing talents translated into outward success, as well as major setbacks. When I combine his experiences (both the high’s and low’s) with what we now recognize as literally decades of progressive suffering from CTE dementia—Dick’s last 20 + years were very troubled. With the benefit of hindsight, it is easy for me and those around him to track the debilitating signs of the disease (withdrawn, aggression, depression, failing executive functioning leading to judgment, decision-making and financial management issues, anxiety, panic attacks, paranoia, and even psychotic breaks with the final result being an overall diminishment of mental and physical capacities). As a Warrior, his natural instinct was to cover these up by fighting back…believing he could overcome…as a Warrior does…as he had always done. As the saying goes in sports, “The great ones play hurt.” This was no more evident than at his induction at the Stark County HS Football Hall of Fame. I knew I would have to do his acceptance speech, which I was honored to do, but that wasn’t enough for Dick as he insisted on taking the MIC to talk. For several minutes he held the audience’s attention attempting to say what was important to him. He could not articulate a single audible word as much as he tried. What everyone in the room did hear, however, was the heart of a champion.

Participating in Dick’s life and reliving it over during the last few weeks was a fantastic journey that I’ll treasure as a brother. Growing up with parents who showered us with love and solid direction; Dick’s life started here at St. Joan of Arc in grade school as an altar boy, voice in the choir, student and athlete. That led to a phenomenal student-athlete experience at Central Catholic, and to Michigan State University where he graduated on time and received 5 varsity letters in baseball and football. Afterwards, canoe trips with older brother John, vacations together, building a family and spending time in MN are just some of the remembrances that will be missed. As his career in business developed, many achievements followed with his responsibilities at IBM, NML and Mid-States Equipment.

For me, however, it’s the loss of a brother who always bailed me out of difficulties while growing up, Dick gave me solid advice when I was about to make a wrong turn, he was helpful beyond expectation on projects involving time and labor, and his subtle yet powerful words of encouragement, just when I needed it “about how proud he was of me” and “how he always referred to me with others as a winner,” left their indelible mark. In football the first rule of an offensive lineman is to protect your Q-back. I could have never asked for a better Q-back to protect.

I found a place to conclude this eulogy in Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace, which is probably appropriate considering the time I’ve taken. The quote comes from the character, Prince Andrew, “Love is life itself. All, everything that I understand, I understand only because I love. Everything is, everything exists only because I love. Everything is united by love alone. Love is God, and to die means that I, a particle of love, shall return to this eternal source called God.”

The wound we feel now losing Dick, as a father, brother, uncle, friend or teammate will turn to a scar. We just have to remember that the scar we carry is a sign that the wound has healed and that life is moving forward.

Thank you.