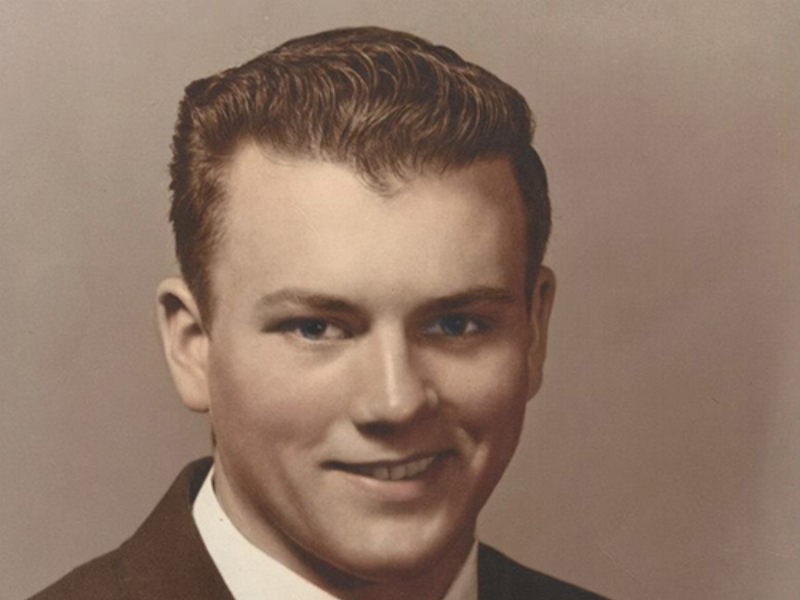

When Patrick was born on December 15, 1981, he was instantly attentive, happy and immediately seemed so knowledgeable about the world and his place in it.

So much so, that we were driven to take this wise little bundle to the window and show him the morning horizon of Pittsburgh and the big world beyond. He seemed so at ease with everything. Patrick would go on to be successful in just about everything he tried. We remember his music teacher telling us he was gifted at playing the Saxophone. We remember his writing teacher saying he was a gifted writer. He was multiplying in kindergarten, but he was multiplying touchdown scores. Football was his greatest love at the time and made the beautiful gleam in his eye shine even brighter.

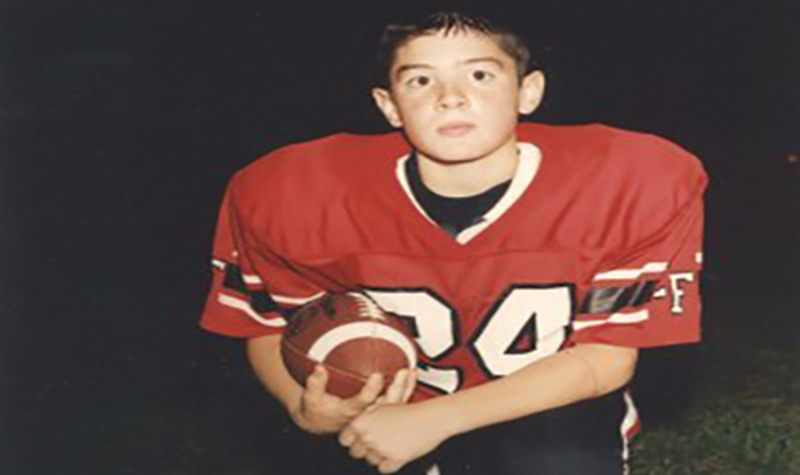

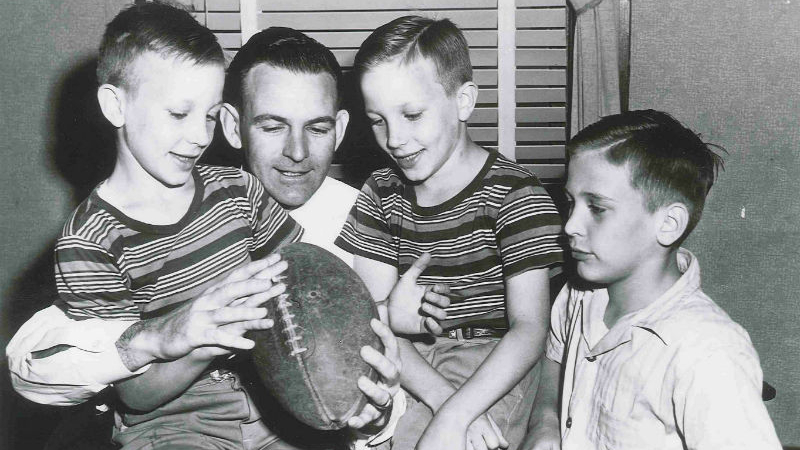

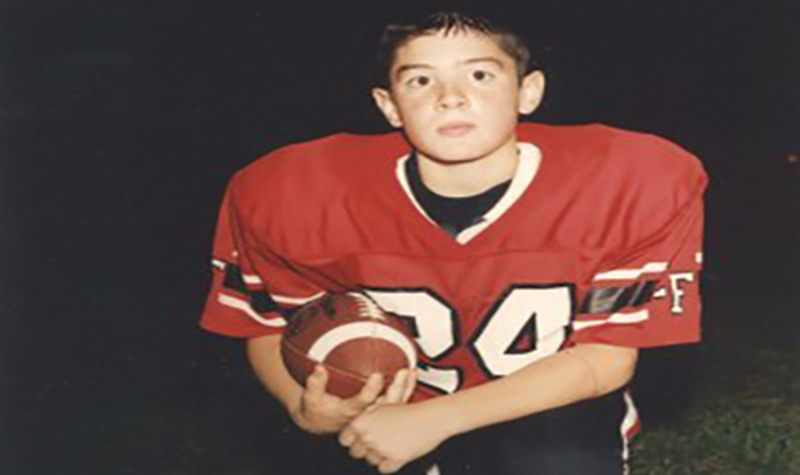

Patrick’s dad was a high school football coach. As a child, Patrick got opportunities to be with “coach” in the locker room, on the sidelines and he developed an immense love of the game. He valued studying it, watching it, but mostly playing it. He started playing for the Elizabeth Forward Mighty Mites team when he was 10. While he did not have immediate success, the wonderful thing about Patrick was that he could excel in just about anything if he wanted it badly enough. He worked hard, he listened to his coaches and he learned to be a great team member. As a gifted athlete, Patrick also played basketball and baseball in grade school reaching the playoffs in both sports.

By the time he reached Elizabeth Forward Middle School he developed into a running back for the football team. He was also playing on defense. He was good enough to be bused to the High School to play in a few JV games. His 9th grade football team won the Keystone Conference Section Championships. He continued playing baseball as well, becoming a fantastic base runner and catcher. His team won the Suburban Pony Central Division Baseball Championship. He was such a fun athlete to watch. He played sports with enthusiasm, joy, and tremendous effort and when he joined the track and field team his 400-meter relay foursome made it to the Pennsylvania AAA Championship Meet.

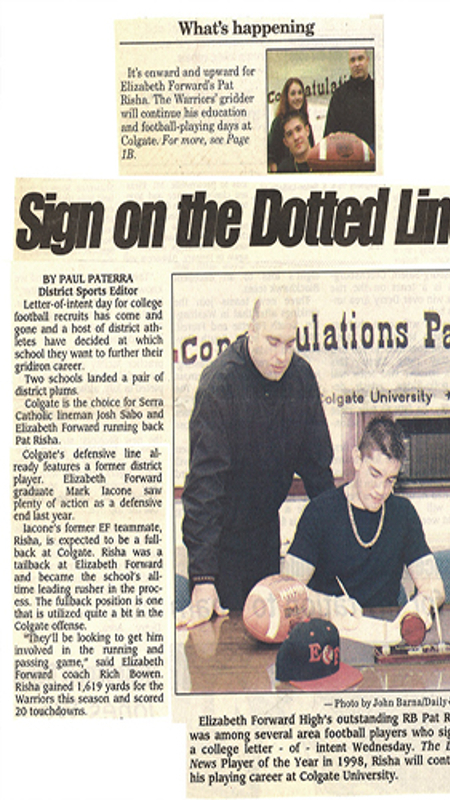

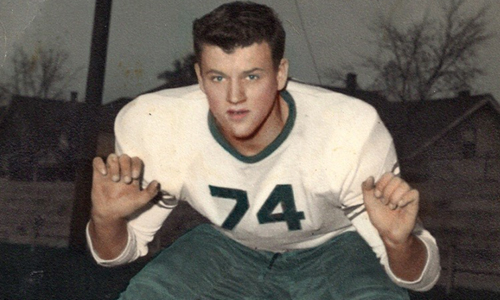

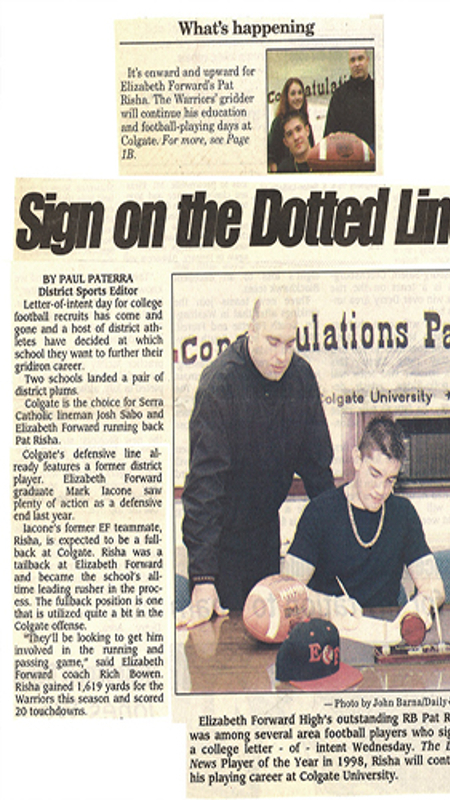

Football really took hold of Patrick during his high school career. He considered football a test of courage and a rite of passage for a young man growing up in Steeler Country in the football rich Mon-Valley. He became a record-setting star player for the Elizabeth Forward Warriors. He played strong safety for the defense. On offense Patrick rushed for nearly 4000 yards garnering school records for most career yards, touchdowns, and attempts, for most season yards, touchdowns, and attempts, and for most game yards. He was awarded the 1999 Tribune-Review Terrific 25 (from 129 schools), the 1998 Daily News Most Valuable Player, the 1998 and 1999 Pittsburgh Post-Gazette Fabulous 22, the 1998 WTAE Athlete of the Week, and the 1998 Fox Sports Athlete of the Week. He was the team Captain for two years and loved inspiring his teammates to play as hard as possible and be good sportsmen. His coach nicknamed him “The Horse” and he became known for never letting the first hit take him down. The papers announced: “Warriors Ride Risha into the WPIAL Payoffs,” which they succeeded in doing both years. He was just a courageous kid playing a man’s game. He was exceedingly brave as he took brutal poundings as every opposing team keyed in on him. As a member of the ELI-MON Honor Society he continued enduring constant battery on the field to keep his dream of an Ivy League Education alive. He gave up baseball to concentrate on football, track and field and to maintain Honor Roll status. During high school he also wrote for The Warrior Newspaper and placed second in the Social Studies Fair.

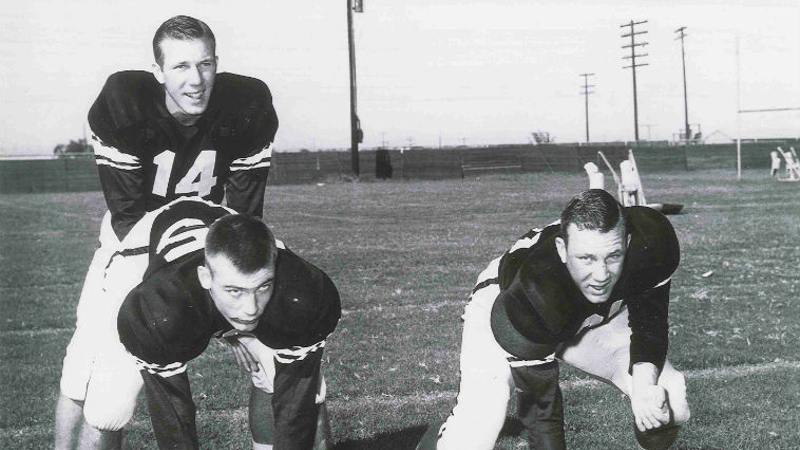

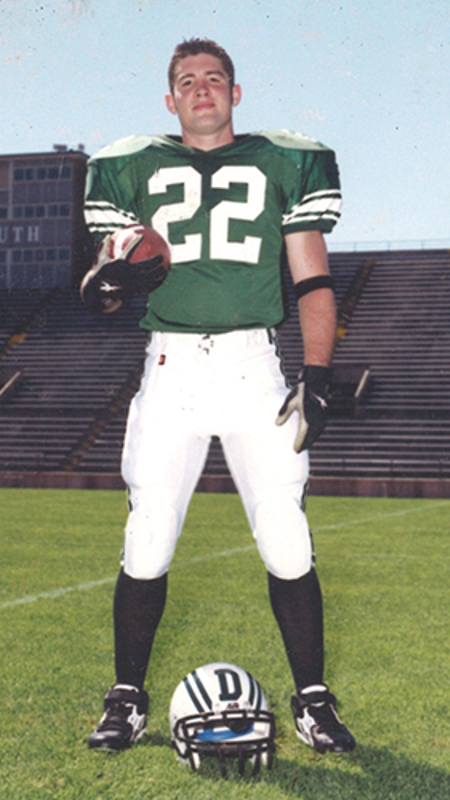

Deerfield team

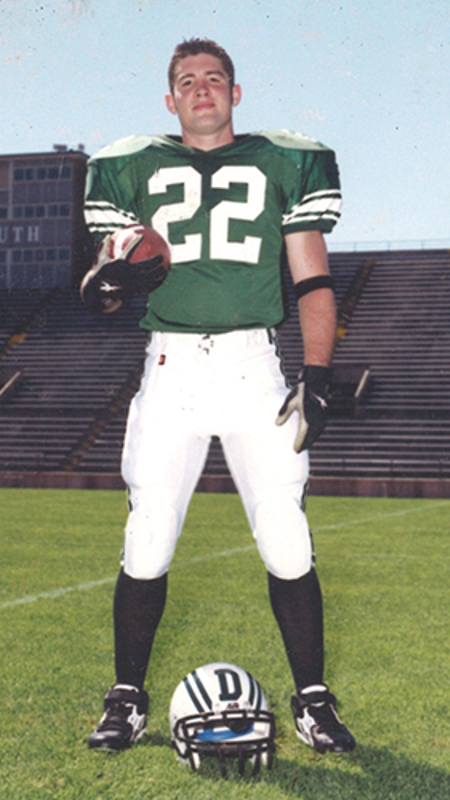

In his senior year, Patrick accepted admission to Colgate University, but then in the summer he had second thoughts and decided to continue his quest for the Ivy League. As a result, he enrolled in Deerfield Academy in Massachusetts as a post-graduate student to further improve his academic standing and play more football. He made lifelong friendships at Deerfield and was the star of the football team. The student body would cheer “RISHA” as he rushed the ball down the field. The following year he accomplished his dream and headed off to Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire. His future was so bright and full of promise.

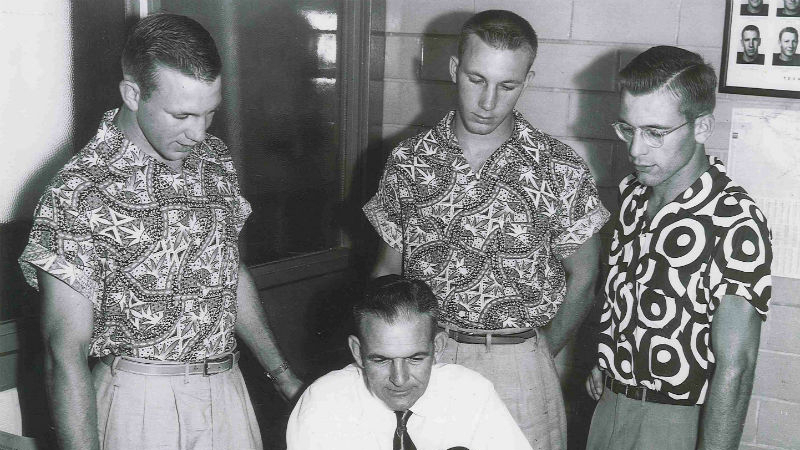

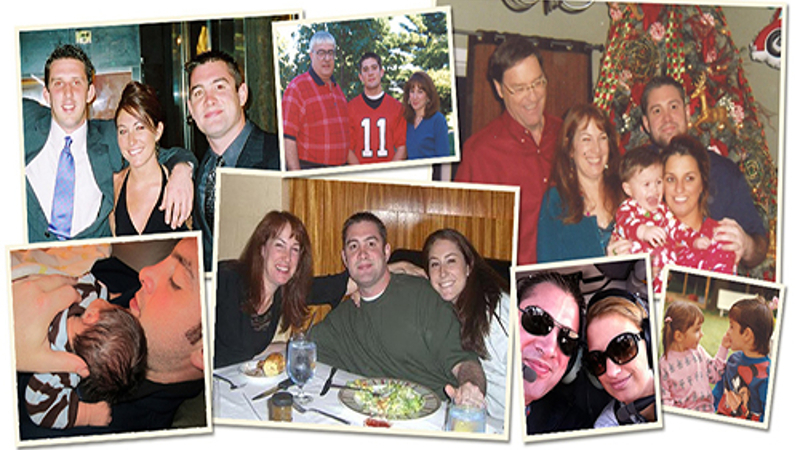

Patrick at Dartmouth

At Dartmouth he was a three-year letter winner in football. He “started” for two years, despite missing a year due to injury. As a freshman running back he averaged over five yards per attempt. He also became a football film junkie and analyst and loved breaking down plays, games and techniques. He was a member of GDX fraternity and was thankful to have so many great friends to call brothers. In fact one of his GDX brothers became a brother-in-law when he introduced his sister, Amanda, to Rich Walton. Patrick was always so protective of “sissy” and maybe in his amazing way made sure she met the perfect guy. At Dartmouth he majored in Government and looked forward to starting a professional career.

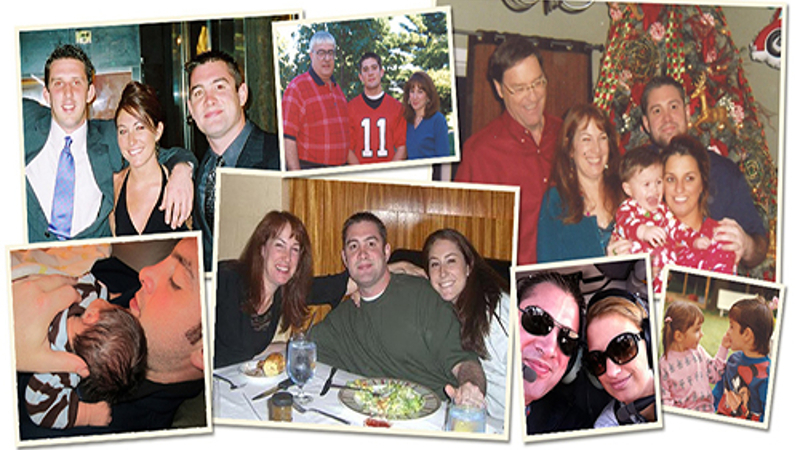

After college, Patrick returned to Pittsburgh to work and help his father who was in failing health. They were best friends. Unfortunately Patrick’s CTE symptoms were beginning to become more prominent and he had a hard time settling into a career. The father and son loved and supported each other until Pat Sr. passed away unexpectedly on October 23, 2010, two days after the birth of Patrick’s son Peyton Jordan Risha (named after athletes of course), who was born on October 21, 2010. As Patrick struggled more and more each day with his CTE symptoms and the sudden loss of his father, the one bright light in his life was his son. Unfortunately Peyton had Patrick in his life for such a limited time, but Patrick did everything he could do to secure Peyton’s future. Patrick’s love will always surround Peyton and when Peyton smiles you can see that same “Patrick gleam” in his eye.

Although so much of Patrick’s life focused on football, he was much more than a football player. He was a devoted son, loving and protective brother, great friend, and the most loving father a child could ever hope for. It is hard not to remember the pre-CTE Patrick who loved watching movies and sports, betting on silly things with friends, eating enormous meals, playing video games for hours on end, golfing, and making people laugh until they cried. He made an impression on everyone he met. He was kind to every person he encountered and could make any one feel important. His heart was huge and he was extremely generous and loyal.

His friends from Deerfield and Pittsburgh wrote:

“There was no one else quite like him. I loved his big smile. He always had a crazy story to tell and I always enjoyed being in his company. He so loved his son, family and friends more than anything in the world.”

“His happiness was contagious and he had the ability to light up any room.”

“The most loyal friend.”

“Patrick was a very generous and caring man.”

“I remember the eulogy he gave to his father that brought tears to everyone’s eyes. I remember his heart, his toughness, and how happy he was to be a father.”

“Patrick was kind and generous to all…when my father passed away, he was one of the first to show up at my door to see what I needed, what he could do or how he could help make it better.”

“He never backed away from a challenge and always competed with dignity.”

“Larger than life, a heart as big as Texas. He loved his family and he loved Peyton.”

And his Dartmouth friends wrote:

“While upperclassmen were usually dismissive to freshmen, Pat was always nice to freshmen running backs and included us in the group. He would drive us to meals and hang out with us at GDX. It may sound insignificant, but it meant a great deal to a bunch of young guys who had just moved away from home for the first time.”

“Pat was one of the funniest people I ever met. He would crack jokes in the meeting room and it made things bearable in lots of ways. He would bust everyone’s chops, including our Coach’s. He was a great character and a fine man.”

“He injected a special kind of energy into situations. He kept life interesting and was a real force of nature.”

“He was highly intuitive (actually one of the smartest people I’ve met) and knew that he could cause issues at times, but he also had your back in a way few other people could.”

“There is no one more genuine than Pat, he told you how it was and the world needs more of that. He was a true individual and I will always remember him as a hard nosed football player and more importantly a great friend.”

“Even as a freshman, he was probably one of the toughest guys in the league to tackle with a ball in his hand. He obviously was a skilled player, but his toughness made him a great player.”

“Pat was loyal. Pat didn’t let everyone in, but when he did and gained your trust, he would do anything for you.”

“He was an amazing big brother and would do anything for his sister, and as a result, he drives me to be the best big brother that I can be to my younger sister. “

“Pat would always make sure I was taken care of, he would let me borrow his truck, buy me dinner, or hook me up with a fancy suit when we had a frat house formal.”

“I think the biggest thing I respect about Pat is that he was a leader not a follower. He did what he did because he wanted to and never did things because it was the ‘cool’ or ‘trendy’ thing to do.”

“At Dartmouth Pat liked to play the role of a ‘tough, blue collar’ football player from Pittsburgh. As a linebacker who frequently butted heads with him in practice I can attest to him being one of the toughest guys I’ve ever known. He wanted to be remembered as that guy, but I mostly remember Pat as being creative, funny, and loyal.”

“He never seemed to forget people and was a real force of nature.”

“Pat turned ‘brother Casanova’s’ lines into a Top Ten joke at our weekly meetings and that will go down as one of the best moments of my time at Dartmouth. He had a room of 60 guys with the attention span of about 3 seconds hanging on every syllable. It was one of many brilliant performances he had over the years.”

“While he liked to play pranks on guys and joke around, everyone knew that he was fiercely loyal and loved all the guys on the team.”

“Pat was a man who accepted people for who they were without judgment. He did not tolerate other people judging his family, friends, or himself and in turn he would not judge other people.”

“Pat had a huge heart and would fight for the people he loved. Without questions, he would give you the shirt off his back, the keys to his car, and would sacrifice his own well-being to help you solve your problem.”

“For those of us who truly had the opportunity to get to know Pat, we knew a man who was creative, funny, sensitive, accepting and above all loyal to his friends and family. He made a profound impact on my life and how I view relationships. He was a man who I am proud to have called a friend.”

“You could always count on Pat being around to talk to. Whether it was a question of some importance or just to shoot the breeze with, Risha would always open his door and talk with you. I can remember many good and hilarious conversations we had together up in his room.”

“Patrick was a great addition to the fraternity and I feel fortunate to have known him. I can still remember his laugh and a certain fire in his eye and his huge smile. He will be sorely missed.”

“Risha always thought about the younger guys and helped us feel like we were all a family.”

“He was always a very funny and unique character that everyone loved having around.”

“My favorite memories by far are the little ones, the little conversations that we would have over a beer while he dominated me in ‘Madden.’ The topics were often very random and I was always stunned by how much he knew/cared about such little things. Pat was just a loyal friend. About as loyal as any person that I have ever met.”

One of Patrick’s Dartmouth classmates said he had to sing a Jack Johnson song for extra credit in one of their classes. The last lyrics of the song were:

“Things can go bad

And make you want to run away

But as we grow older

The horizon begins to fade away…”

Patrick is no longer here to tease us, hug us, or help us, but in many ways his heart and love are all around us. We lost him much too soon to a disease that was created by his hard work, determination and will to succeed despite tremendous obstacles, and his efforts to please his friends, family and schools. No one sought success and friendship more than Patrick but CTE took all that away and left him with a brain that was failing him at every turn and changing his essence of love and caring.

Patrick left behind a wonderful legacy of being true to self, loving, protective, caring, and loyal. Sadly, CTE was eroding all that made him so special. Even the special glint in his eye was hard to find in his last few months. Suicide is a tragic yet common result of CTE and it worked its way into his brain as it has done so many others. However, it never took away his soul. We will always have that. Patrick’s son, Peyton, will always have that.

This was not the life we wanted for Patrick, but we accept his sacrifice and know he is guiding us to help others in new ways and with great purpose: to save other young minds from the devastation of CTE and to prevent this heartbreaking loss in others.

Read the New York Times article on Patrick Risha here.