Todd Eagen

Ray Easterling

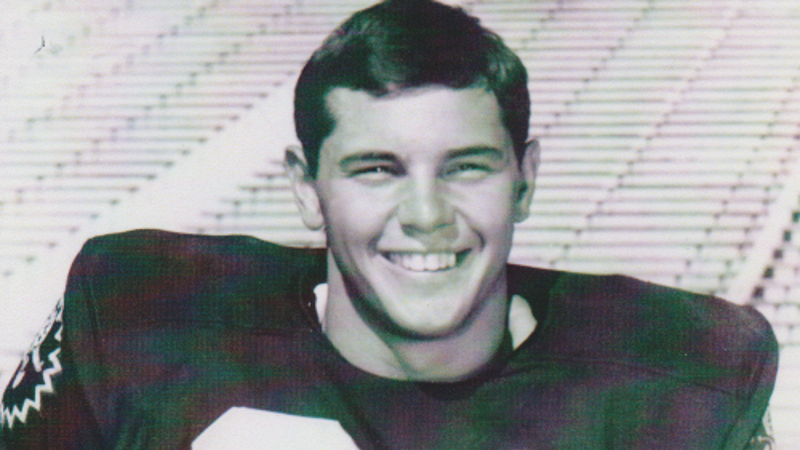

Born to Elmer and Vivian Easterling in Richmond, Virginia, on September 3, 1949, Ray was the second of three, athletic boys. He grew up in what was a rural setting in Chesterfield County, roaming the creeks and fields as little boys do. He wrote in his third grade biography that he wanted to be a professional football player after watching his cousin, Carroll Dale, on television playing for the Green Bay Packers.

In the eighth grade, Ray was 4’10” and weighed 98 pounds. He was a wiry, little fellow! He was the one in pickup football the quarterback always told to “go long”. He tried out for his school’s football team, but they wouldn’t give him a uniform. Seeing his son’s intense desire to play football, his dad took him to a private school, obtained a scholarship for him, and the rest, athletically, is history.

Nothing had ever come easy for Ray. He was a fighter and a scrapper. His friend, Jimmy Lewis, would say that he had to rescue Ray from his scrapes!

At Collegiate School, Ray lettered in five sports and was voted the best all-around athlete his senior year. Then came the search for a college to give him a scholarship. His dad took him around Virginia and North Carolina to no avail. Finally, because his brother, Robert, was going there, he walked on at the University of Richmond. By his sophomore year he earned a scholarship to play football for UR.

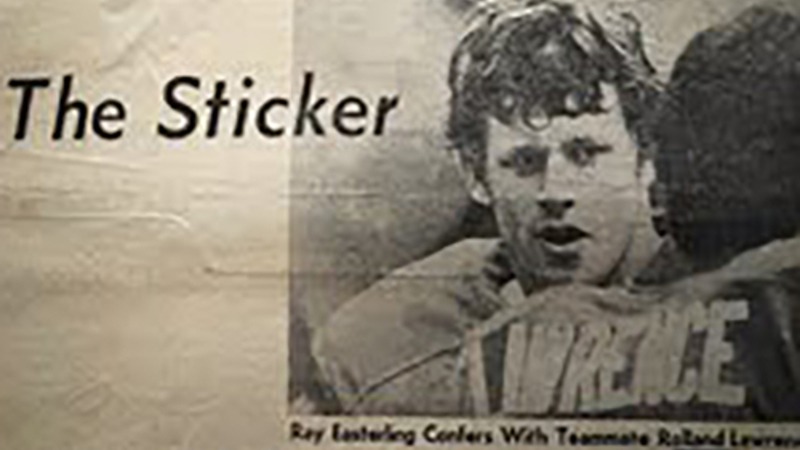

His junior year play at cornerback was outstanding. By the time spring practice rolled around, pro scouts were in town to watch him. But it wasn’t to be an easy road. An injury to his knee put him in a cast for six weeks. Rehab included running the hills in a local park with his brother, Robert. He came back from the injury to play well his senior year at UR with numerous awards including All Southern Conference and Little All-American. He played in the Coaches All-American game. Coach “Bear” Bryant made a memorable impression on this college senior. In the spring of 1972, Ray was drafted by the Atlanta Falcons in the ninth round.

Arriving in Atlanta was a dream-come- true for Ray. If there wasn’t a party, Ray started one. But by the time he was back in Richmond for the off-season he was crying himself to sleep at night. He wondered, “if you get everything you ever wanted and still feel empty, what is life all about?”. The summer of 1973, Ray knelt in a cow pasture in rural Virginia and trusted Jesus Christ as his Lord and Savior.

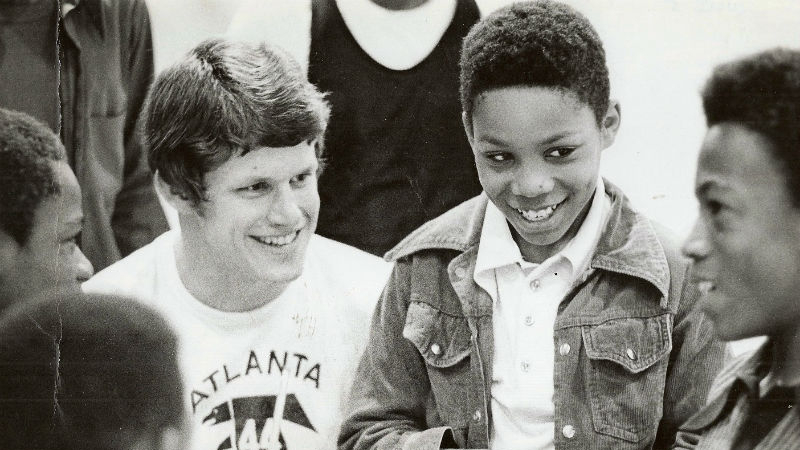

I share that in this context because it is the key to who Ray was when I met him. He was passionate about sharing his faith with anyone who would listen. He went from aimless youth to responsible, leadership on the Falcons’ team. When he returned to Falcons’ training camp that year, a changed man, his coach, Norm Van Brocklin, told him “if you hadn’t changed, we were going to cut you”. Ray believed that God gave him back the very thing that he had always wanted to do.

His passion for Christ led him to speak to youth groups, conferences, and retreats during the football season and all throughout the off-season. He made himself available to anyone who was in need of answers or help.

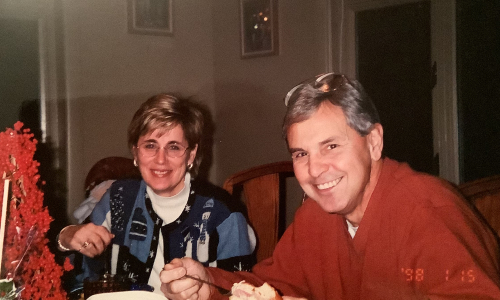

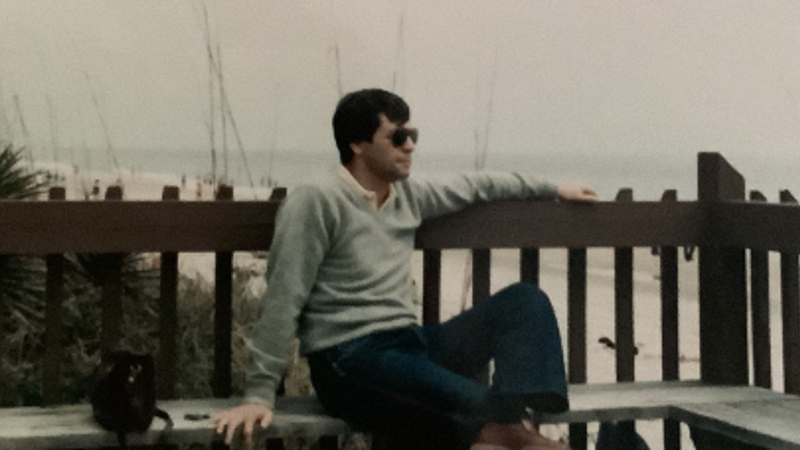

In January of 1975, Ray returned to Richmond and the Bible study he founded with his dear friend, Earl Nance. It was there that I met him. I was a senior majoring in music at Westhampton College (UR). Ray’s enigmatic personality and genuine faith were magnetic to me. I quickly fell in love with his ready smile, gentle leadership, hunger for God and His Word and gentlemanly ways. I was beyond excited when, even after I graduated and returned home, a dozen roses were delivered. It was at that point that my parents knew that something more serious than just dating was going on!

Ray proposed that summer and we were married on January 3, 1976 in Richmond. It was a fun life of speaking engagements coupled with working out in the off season; working hard to make the team and playing the games during the season. We were newlyweds; very much in love and enjoying our life together.

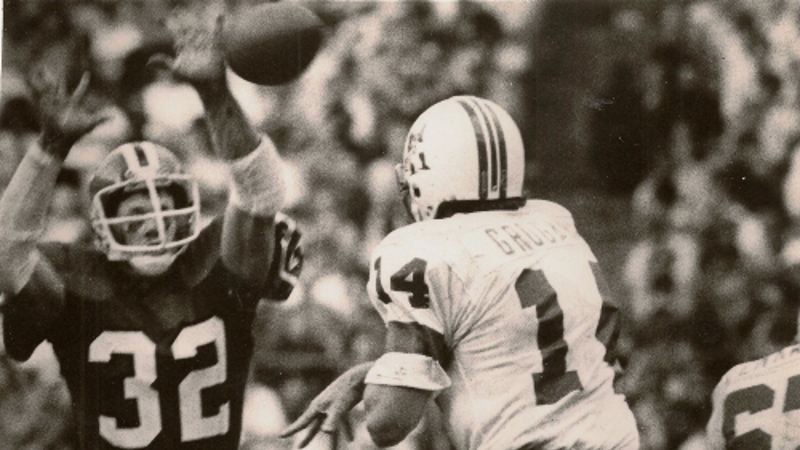

In 1974, Ray started at safety for the Falcons and played through the 1979 season. During his career, he tackled the likes of OJ Simpson, John Riggins and John Cappeletti. His best game was against Walter Payton in October of 1977 where Ray had 20 unassisted tackles and two interceptions. His job was quarterback of the secondary and he reveled in the task of reading the quarterback and communicating with his fellow defensive backs. That year, the Falcons’ “Gritz Blitz” held their opponents to 129 points, an all-time record that has never been broken.

Ray gave his all on the field. There was never a time when he considered loafing or giving less than one hundred percent. Ray never mentioned his concussions. It was a part of the game that no one ever saw except when a player was knocked out. He was seriously injured during the 1978 season with a dislocated elbow. It disabled him to the point where he had to use his head more to tackle.

During his final training camp in 1980 with the Falcons, he shared with me that he was getting stingers and seeing stars a lot. His right thumb went numb and the muscles in his arm began to atrophy. The team trainer took notice when, after not sleeping several nights, Ray asked for a sleeping pill. The trainer also saw the neurological damage apparent in his arm. After a series of examinations and being told that returning to play might bring paralysis, Ray decided to retire from professional football. He saw this as God’s merciful way of showing him that it was time to walk away.

During the 1980s Ray successfully built a financial services business. We enjoyed prosperity to a level not experienced during football. We had investments and a portfolio that would be the envy of most middle class Americans. Ray attributed his success to God’s blessings.

Upon turning 40, Ray began to experience serious problems with insomnia which, in turn, led to depression. He left the financial services business along with its excellent residual income and decided to take a new direction. He tried to start several businesses on his own over the next 9 years. His description of these decisions was “uncharacteristic” and “I didn’t do the due diligence I would normally have undertaken”. I found that I was living with someone I did not recognize. My normally disciplined husband took chances with our finances that ended in losing our house and all our savings.

Interaction with our friends gradually dwindled; he pushed away some very close friends in fits of temper. Ill humor was a constant companion.

In and out of various professions, Ray had difficulty working with others. It wasn’t until he brought his business home in 2007, that I noticed his inability to organize and keep track of details. Never one to tolerate messiness, his desk was a maze of phone messages and incomplete business plans.

I was at a loss to know what had happened to my precious husband. In December of 2010, I saw a blurb on the Internet about a former NFL player who had CTE. It took me to the case studies Drs. McKee, Stern, Cantu and Chris Nowinski had done on former athletes who were diagnosed with CTE. The symptoms and behavior matched Ray’s. I was and am so grateful to them for making their findings known.

The spring of 2011, Ray was diagnosed with dementia due to the concussions he sustained in professional football. We finally had our answer to the questions of “what” and “why.” The feelings of helplessness mounted as Ray’s symptoms worsened. The medicines available could only promise to stave off the march of the disease temporarily.

With the conviction that his time on earth was complete and that he was “ready to meet” his Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ, Ray took his life on April 19, 2012. The subsequent autopsy revealed moderately severe CTE in Ray’s brain.

I hope and pray that sharing Ray’s story has helped you understand what a devastating disease CTE is and how important the work that the Concussion Legacy Foundation and BU CTE Center are doing. Please consider doing all that you can to help in educating your friends and promoting this research.

Most of all, to God, be the glory! For He sustained us through a difficult time with His peace and provision.

Read more about Ray’s story in the New York Times here, and in a Christian Families Today newsletter here.

Dan Ehle

Andrew Erker

The morning of January 11, 2017 started out just like any other morning. Andrew got out of bed early to send me off to work with a big hug, kiss, an “I love you” and his typical, “Whatever you do today, just be a good person.”

Andrew’s number one priority in life was to be a good person regardless of the circumstance. He never failed to live up to that standard he set for himself. I would always receive a text late morning just to check in and see how my day was going. Not hearing from him at all that day in January made me a little uneasy. Driving home from work that night I knew in my gut something was very wrong. Andrew died by suicide earlier that day in our home.

This horrific tragedy came as a massive shock. Surely that wasn’t him. It didn’t make sense. Andrew had such a love for family, his friends and me. His enthusiasm for life, nature and wildlife was unmatched. He would light up a room with his smile. Andrew was the most selfless man I had ever known. His intentions to make everyone happy and be a better version of themselves were as pure as they come.

Something in his brain was not right that day and hadn’t been for a long time. Andrew was not the type to complain or ask for help. He refused to burden or worry anyone. He wanted to do it all himself and was determined to do so. I believe he suffered internally for longer than I knew or could ever imagine. Andrew’s sense of humor was one of his best qualities. He was constantly making everyone around him smile and laugh. For as long as I knew him he would joke about football messing up his brain. He believed it made him “stupid” even though he was thriving at work and nothing about his daily life made it seem like he was missing a beat. Joking about it I believe was his way of trying to tell me something wasn’t quite right without making me worry. When Andrew and I started talking about having a family his number one rule was that our kids would not play football. It was becoming clear to me that he was truly worried about the toll football took on his brain.

Andrew and I met at a bar in Kansas City in 2014. I was 22, still in nursing school and he was 27 living in Lincoln, Nebraska. He was home for a weekend and out with friends when we met. From the moment I met him I knew he was incredibly special and early on we both knew it was meant to be. He moved back to Kansas City the following year and we were married in April of 2016. Nine months later he was gone.

Andrew played tackle football from the time he was a child through his college career at Kansas State University, where he played safety. Andrew was not the biggest player on the field, but he was tough and known for his hard hits. I believe Andrew suffered several undiagnosed concussions during his time playing football. He told me about several games he didn’t remember after playing in them and times where he just didn’t feel quite right after games.

A few months before he died, I started noticing the forgetfulness. He couldn’t recall certain conversations or plans we made. Towards the very end of his life he became more irritable and his patience was diminishing. Although his anger seemed to be heightened in the last couple weeks of his life, I do feel as though his emotions were fairly well controlled. It seemed as though Andrew was somehow able to mask many of the typical signs and symptoms of CTE.

Andrew’s family and I decided right away to donate his brain based on his football history and his recent behavior. Andrew was always helping others so when donation became an option I knew he would jump at the chance to try and help save someone else’s life. Boston University was an obvious choice for us, and I could not be more grateful for how we were treated and supported during this incredibly difficult time. I felt as though Andrew was respected and appreciated by the researchers from the UNITE Brain Bank from day one. Seven months after he died, Andrew was diagnosed with Stage 3 (of 4) CTE. We were all shocked to see such advanced disease in a 30-year-old.

I want people reading Andrew’s story to understand the dangers and possible effects playing tackle football as a young child can have on your brain and your life. I want people to know that CTE can happen to anyone with a history of repeated head impacts like Andrew had. Choosing to put your child in tackle football at a young age could end up destroying their life and leaving their loved ones completely devastated. I know Andrew would have much rather sacrificed his football career for his life than his life for his football career.

I feel incredibly lucky to have fallen in love with a man who I know fought like hell against an uncontrollable brain disease to protect his friends and family.

__________________________________________________________

Suicide is preventable and help is available. If you are concerned someone in your life may be suicidal, the five #BeThe1To steps are simple actions anyone can take to help someone in crisis. If you are struggling to cope and would like some emotional support, call the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988 to connect with a trained counselor. It’s free, confidential, and available to everyone in the United States.

Are you or someone you know struggling with lingering concussion symptoms? We support patients and families through the CLF HelpLine, providing personalized help to those struggling with the outcomes of brain injury. Submit your request today and a dedicated member of the Concussion Legacy Foundation team will be happy to assist you.

Larry Facchine

Larry Facchine grew up as an outstanding athlete, excelling in every sport he participated in – basketball, baseball, golf, tennis, and primarily, football. He was raised in Vandergrift, Pennsylvania, your typical small western Pennsylvania town where, like in the majority of Pennsylvania towns, everyone looked forward to Friday night high school football. There could have been no better place for Larry to spend his school years. His last four years of high school found him on the football field every Friday night doing what he loved.

After graduating from high school, he accepted a scholarship to play for Arizona State University. He loved ASU and he loved playing for the Sun Devils. He played both quarterback on offense and safety on defense and was a three-year letterman. He played hard and got hit hard. During one game, he was hit so hard his helmet broke. His senior year in 1963-64 was an exceptional year. The team had an undefeated season and he received the “Mr. Hustle Award” given for outstanding performance.

Larry and I met in the summer of 1969 when he returned to Vandergrift after coaching in Arizona. I had never met anyone who had his drive. He was tireless and relentless in his thirst for learning about everything imaginable. Nothing was ever “good enough” for Larry. He always tried to make himself or what he was doing better. I know these traits are what helped him succeed in everything he did.

I had just signed a contract for my first year of teaching and Larry had taken a teaching and assistant coaching position at the Jeannette School District nearby. He worked with an incredible group of young players. In his third year with them, they won the Western Pennsylvania Interscholastic Athletic League Championship. It was one of the proudest memories of Larry’s football career. It made him realize how coaching, mentoring, encouraging others, and watching them succeed were what gave him the most satisfaction. After that third year, Larry accepted a head coach and athletic director position in another district, but he took with him a special, life-lasting bond he had fostered with so many of the players.

In the years that followed, along with coaching football, he gave golf and tennis instructions to youths and adults, became an emergency medical technician, taught golf at a community college, and began practicing intently to qualify for the senior golf tour in the future.

About seven years after he left Jeannette, his former quarterback stopped at the house for a visit. He was working for a water treatment company and had his boss with him. He had told his boss that Larry would be a perfect representative for the company because of his drive and personality. And that was the beginning of his career in the water treatment business. After working with the company for nine years, he decided to begin his own company and did so very successfully. And still he continued with giving golf and tennis lessons, coaching Little League, and practicing his golf to achieve his goal of joining the senior golf tour in the future. He never stopped touching lives and encouraging those he mentored.

Many years later, in 2011, Larry noticed he began “losing” words. He would know what he wanted to say but couldn’t retrieve the words. He thought it might be the beginning of Alzheimer’s Disease, so he met with doctors who put him through extensive intellectual and medical testing. It was determined he didn’t have the beginning of Alzheimer’s but did have blockage of the blood flow to the left side of the brain due to head trauma. Since this area of the brain was the language center of the brain it explained the occurring language problem.

Larry had great respect and confidence for our family doctor. We kept him informed about the Alzheimer’s study, the language problem, and all his developing mental and behavioral changes. It was our doctor who first mentioned the possibility of CTE. That was quite a surprise because it had been 46 years since Larry had been on the football field. As time went on, Larry started suffering periods of depression, thoughts of suicide, and unexplainable bouts of anger. Not only did he have trouble communicating but he had difficulty processing what was being said to him. Because Larry would only see our family physician, our doctor consulted with his neurology staff for possible medications that might help the changes being experienced. When medications were not helping and Larry’s condition was worsening, our doctor suggested a hospital stay to try to get a regiment of medication that might help manage the ever-changing conditions Larry was experiencing.

Larry spent 11 weeks in the hospital and finally came home with a treatment that worked. The treatment didn’t eliminate his problems but helped with them. Unfortunately, this treatment also created other new problems and took so much more away from him. He had to get used to a now unfamiliar home and no longer knew our friends and relatives.

Conditions for him worsened and after six months at home I realized I could no longer give him the care he needed because of the ever-changing behaviors. After searching for and visiting many facilities, I finally found Newhaven Court Memory Care which proved to be his home for the next two years beginning in January 2018. It was heartbreaking to face this major change in our lives.

Surprisingly, Larry adjusted to the change better than I ever would have imagined. The director of the Center took a personal interest in CTE when I told her that might be what we were dealing with. She researched CTE and learned as much about it as she could. She trained her staff to provide phenomenal care for Larry. At this time, he no longer knew people’s names and could not carry on a conversation or answer simple questions, but he seemed more content and calm. Within a few months, because his physical abilities were diminishing so rapidly, he started receiving the care of a wonderful hospice group. I spent many hours with him every day and was awed by the love and care the group continually gave Larry. As he lost the fight against the effects of what we believed to be CTE and could no longer speak or walk or eat, I was at least at peace with knowing he had had the best possible care.

Larry passed away on December 22, 2019. He was 78 years old. His brain was then studied at the UNITE Brain Bank, and the results of the CTE Neuropathology Report from Boston University CTE Center confirmed Larry did have CTE in addition to severe Alzheimer’s Disease. Knowing this didn’t change my sadness or the unbelievable loss I felt, but at least I had a reason for all that he had suffered. CTE had taken away many healthy years that he could have had, but it didn’t take away the person he was and the lives he touched. Even now I am constantly reminded of that by visits, phone calls and letters from those he mentored. That, indeed, was his legacy.

Becoming aware of the Concussion Legacy Foundation and all the research and studies being conducted to advance public understanding of CTE gives me such hope for the future. So many strides have already been made and much more will be achieved in the future because of the determination and hard work of everyone involved in the Foundation. I am forever grateful for their assistance and support and I am proud to be a part of it in some small way on behalf of my husband.

Dennis Farrell

“Don’t take life too seriously.”

This was the last wisdom Dennis shared with his children and family.

Dennis the Menace and Iron Papa Bear were his given nicknames. These offer you a glimpse into the life of this son, brother, father, and friend. He was a kind, loving, generous, strong man with a bright smile. He was born in Miami on the third day of the third month and was the third of nine children; three was always his lucky number. His family relocated back to Illinois when Dennis was a toddler. He had many fond memories growing up — causing trouble with his five brothers and neighborhood friends. His three sisters were around to try and keep them in line.

Learning didn’t come easy for Dennis. Being one of nine children, he needed a way to stand out. Exceling at sports was his thing. His success helped to deflect bad attention from his grades. He had natural talent, and he gave it his all from a very young age. He played baseball, basketball, and football. Football was Dennis’ pride and joy, and he starred at linebacker. He played for a junior league for three years, before entering Gordon Tech High School in Chicago. There, his incredible talents on the field earned him a full football scholarship at Illinois State University. A friend said, “I saw him get his bell rung multiple times. We didn’t know what the lasting effects were; we just got back up and played.” He played three and a half years before suffering a career-ending knee injury. He changed majors and knew he wouldn’t complete his education in four years, leaving Illinois State to attend a trade school. Following in his father’s footsteps, Dennis became a devoted millwright (heavy machinery mechanic). Later in life, he coached football teams in his hometown. He loved to watch the game.

Dennis had two children. He was married to their mother for 14 years. After their divorce, he never remarried. He was a devoted father and was never considered a part-time dad. Whether it was his son’s games or practices or his daughter’s musical performances he never missed the opportunity to cheer them on.

“We were and will always be a family, even as unconventional as we were.”

Dennis loved the outdoors. He liked to sail on Lake Michigan, golf with friends and family, and go on walks/hikes. He considered himself a born-again hippie, free spirit and all. He was also a craftsman at heart. He loved creating beautiful furniture pieces, winding stairs, decks, and any remodeling projects. He often worked with his brothers to complete home renovations and projects at one another’s homes.

Dennis experienced a lot of life. He traveled to where work was available in his trade, offering him many different sceneries. He traveled yearly to Arizona to spend time with his mother. This was special considering he was one of nine. Family was important to Dennis and he spent a lot of time with his brothers and sister who lived nearby in Chicago. They would attend festivals, garden together and have the best barbecues. He relocated to Miami for several years working with the millwright union there; he loved being back in the city where he was born. When not working, he enjoyed activities on the ocean. He watched both of his children graduate from college, get married, and he was able to walk his daughter down the aisle. His son granted him the title of grandparent (known to his grandchildren as papa). He enjoyed spending time with his two grandsons and attended many of their various sports events. They brought light and joy into his life. Usually you’d see Dennis sporting a tie-dye t-shirt with a feather earring in his ear.

Other than behavioral occurrences, no one thought Dennis was being anything other than himself. All our lives our dad was different, unique, and one-of-a-kind. We learned from him to accept people for their differences, as you’ll come to appreciate them in the end. In 2012, he had a cardiac episode that led doctors to perform a triple bypass with a mitral valve replacement. It was an extensive ten-hour surgery. It took him eight days to come off the vent. Once he was off the vent and coming around, he bounced back fairly quickly. He was doing great. He visited friends, engaged in light activities he enjoyed, and kept himself busy. He did retire from being a millwright after 36 years due to his heart.

In 2015, we started to see signs that were the beginning of the end, although no one knew at the time. He was making poor choices, forgetting to pay bills, and misplacing things. Over the next three years, he stopped engaging with friends. His mobility decreased and he couldn’t participate in the activities he loved. His children stepped in to help and find out what was causing these changes. We went to ten different doctors trying to find answers. Specialists would point to another one saying it wasn’t in their realm of medicine.

Dennis’ children helped manage his finances, insurance paperwork, and care. They shared doctor appointments and kept one another updated. The last couple years of his life family pitched in to help with his care. His children’s mother took him to a couple doctor’s appointments. A sister offered guidance and support, with her knowledge of the medical field. One of his brothers visited and took him out to different places. His other siblings gave motivation through messages and phone calls. As his symptoms and ailments progressed and we read more information on Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy, or CTE, it started to sound like it fit the best with what we were seeing. The movie “Concussion” felt all too real. Doctors had told us there was no way Dennis had dementia; it was all behavioral. Another said, “he didn’t get hit enough times to have CTE” and that they could help him gain all his independence back. Many said they had no idea why everything was declining rapidly. They tested him so many times for so many different diseases. Traveling to Boston in December of 2017 with his daughter and son-in-law for Diagnose CTE Legend Study was the first time we felt like he was understood.

His wishes were to have his brain and spine donated to the UNITE Brain Bank. He wanted to donate not to help himself but to help others in the future.

Dennis had a great cardiologist that assisted when we needed advice or direction. In August 2018, we met a neuro-muscular specialist who worked so hard to help us. She came into the picture in the last quarter of the game and found answers. In September 2018 he was diagnosed with ALS — a couple years after the first symptoms appeared. Through all the struggles Dennis never gave up and did everything they asked him to do. He did daily PT and OT, until three days before his passing. He worked so hard. He wasn’t ready to leave his family. Surrounded by his children, on October 31, 2018 (Halloween), he passed away from complications related to ALS.

Dennis passed knowing he wasn’t going to find answers. He found peace knowing that we, his family, would get answers about what he was suffering from. More important to his final wishes, he knew his donation would benefit others in the future. Researchers at the UNITE Brain Bank discovered that he had Stage III CTE with ALS. Dennis Farrell loved football. We know for sure he still would have played the game he loved, but he would have played safer.

The best advice we can offer is keep notes and make observations of your loved one. You know them best. Spend lots of time and have lots of patience. Don’t stop trying to find answers. Advocate for those who can’t fight for themselves. You will find someone and a place to help. The staffs at the Boston University CTE Center and the Concussion Legacy Foundation have been amazing. They offer guidance and advice that many of the professionals in Chicago he saw couldn’t provide. We are grateful to the whole team in Boston.

We will forever love our father and will honor him every day for the rest of our lives. We miss him but know he is in a better place. Dennis’s famous sign off: Peace, Love, & Bell-Bottoms!

Dennis Fase

Dennis was happiest when surrounded by family and friends. He adored the kids and I, and would tell anyone that would listen just how proud he was of us. He had a great group of friends and was well respected in the community. Through many years of hard work, putting in long hours at the office, many times at the expense of his family, Dennis built a successful career as a financial advisor. From the outside, it appeared Dennis had it all. There was no way to know that his brain was a ticking timebomb and that in just a few short years, Dennis would turn into someone almost unrecognizable.

Full-time lineman

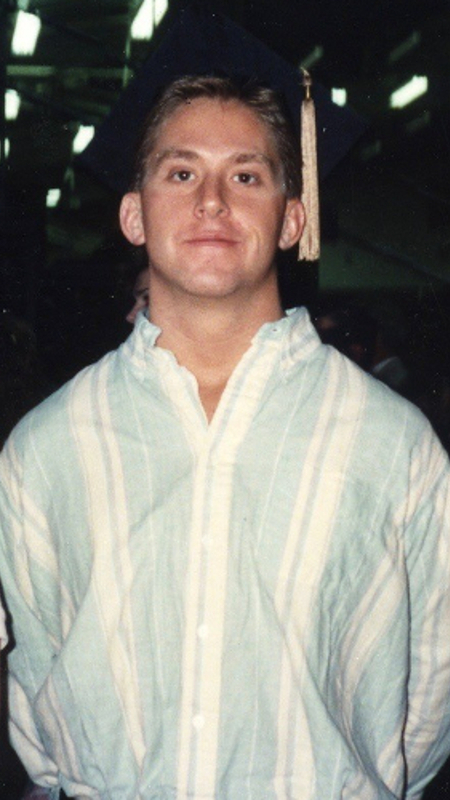

Dennis was born in Papillon, Nebraska in 1967. Growing up, he loved the Tom Osborne-coached University of Nebraska football teams and earned himself a scholarship to play offensive line for Kearney State University in Kearney, Nebraska. There, Dennis treated football like his job. Dennis was a perfectionist and had high expectations for himself and everyone around him. He did not do anything halfway.

After football, Dennis directed his all-in mentality towards the next chapter of his life in the business sector. When he played his last game in 1989, Dennis weighed 265 pounds. By the time he graduated in 1990 with a degree in finance and economics, he was down to 180 pounds. This amazing feat speaks to the incredible discipline Dennis possessed.

It felt to me that Dennis was obsessed with exercise. Looking back, I see that fitness was part of his mental health.

On top of his game

Dennis and I met at a training conference for Mutual of Omaha. Dennis was a good-looking guy with a sense of mystery about him. His work ethic and sense of humor were an immediate draw. It took some time to break through his shell and really get to know him but once I did, I was all in.

In 1997, Dennis started working for Merrill Lynch as a financial advisor. He was clearly talented at acquiring new clients and his genuine interest in their well-being allowed him to form long term relationships with many of them.

Dennis was an intensely disciplined man and stuck to a strict routine that supported both his work success and the standard of physical health he held himself to.

His alarm went off at 4:00 a.m., he’d be out of the house by 4:45 a.m., and be the first one at the gym when it opened at 5:00 a.m. After the gym, Dennis was one of the first to arrive at the office and one of the last to leave. This high degree of discipline was a key factor in his success.

Ben was born not long after Dennis started with Merrill Lynch. Dennis was working long days and weekends to get established and missed out on so many firsts. Things had not changed much by the time Olivia and Alex were born.

With Dennis obsessed with Nebraska football and me a huge fan of The Ohio State Buckeyes, sports became a huge part of our family. Dennis worked long hours, but he always made time for the kids’ sports. He was a constant on the sidelines or in the stands for every soccer, basketball, or football game.

Dennis’ spare time was limited, but he cared deeply about supporting local nonprofits. He sat on multiple boards and was a fixture at fundraisers for the local YMCA, hospital, and other organizations. He was just a really good man.

“This can’t be Dennis”

When Dennis hit his early 40s, I began to notice some oddities in his behavior. It started with forgetfulness. He couldn’t remember entire conversations, many times asking the same questions over and over. He was short tempered with the kids and seemed much more anxious and on edge. I wonder now if he knew something was happening with his brain?

Although these changes were slight, it was easy for the kids and I to notice considering how disciplined Dennis normally was. Around this same time, I read an article about former NFL tight end and Colorado Rockies executive Keli McGregor, who was diagnosed with CTE after his death in 2010 at age 47. The way Keli’s wife Lori described Keli’s late-life behavioral changes sounded all-too familiar to me. Knowing his football history, I began to wonder if Dennis too was suffering from CTE.

Despite what we were noticing at home, Dennis was able to keep it together at work, successfully closing one of the largest deals in the history of Merrill Lynch. He was recognized nationally for his achievements. Looking back, I think Dennis used everything he had to mask his heath issues at work but was unable to keep up the front at home. We suffered the brunt of his changing personality.

In 2016, a new set of problems emerged for Dennis. In addition to ongoing memory loss, he was showing more progressed cognitive impairment and suffering from severe neuropathy in his legs. The neuropathy created an awkward gait for Dennis and caused him to stumble frequently. This change in his outward appearance was a huge blow to Dennis as he prided himself on his put together presentation. The sudden motor function issues led to countless neurology appointments in search of answers. Neurologists ruled out a brain tumor and diagnosed him with Guillain-Barre Syndrome, a rare disorder where the body’s immune system attacks nerve cells.

To add to the stress of Dennis’ medical problems, his business partners had decided to dissolve him from the partnership. We were now faced with financial worries as well.

We saw moderate improvement with the IVIG treatments Dennis was receiving for Guillain-Barre, but the cognitive piece seemed to be worsening. We took Dennis to University of Colorado Health for a more rigorous neurological exam. I voiced my concerns regarding possible CTE but unfortunately, my concerns led nowhere. A physician did note Dennis had elevated liver enzymes and asked him if he had a drinking problem. Dennis denied any sort of problem and because he was a master at hiding his addiction, it never crossed my mind that some of Dennis’ health problems could be a result of alcohol abuse.

Frustrated that he still wasn’t improving, we took him to Mayo Clinic, hoping to get some answers. After a week of testing, there was still no clear diagnosis. I once again mentioned my suspicion of CTE, and once again, my concern fell on deaf ears.

“Is this our new normal?”

Dennis’ behavior was becoming increasingly erratic and he was forced to take a leave of absence from work. He was showing signs of paranoia, impulsivity, and recklessness. I don’t know how we survived the next year. Dennis would disappear for hours at a time with no indication of where he was going. If asked, he would become angry and say he didn’t need to be tracked like a child. The kids and I lived in a constant state of fear, wondering if he was ok.

When he was home, he was either in bed or sitting in the chair with the TV blaring. Where he was once the envy of the neighborhood because of his lush, immaculately kept yard, Dennis had completely lost interest in the things that had formerly brought him pride.

What made Dennis’ health problems so difficult to deal with was his complete denial that there was anything wrong with him. He thought his behavior was perfectly normal. The frustration of his erratic behavior was alienating Dennis from the kids and I as well as his friends. His verbal tirades and behavior had become so toxic that the kids didn’t want to be home alone with him.

The loss of his business partnership crushed Dennis. He felt betrayed by partners that he had worked with for more than a decade. He took immense pride in his work and the loss of their trust and respect put him into a downward spiral from which he would never recover.

We don’t know what triggered the admission, but in May 2017, Dennis admitted his drinking problem and said, “I can’t do this alone; I need help.” We immediately got him into an inpatient rehab program.

“While I was shocked to hear my dad admit he had a drinking problem, I was also relieved that we finally had an answer for his medical problems and changing personality,” shared Olivia.

Following inpatient rehab, Dennis continued with intensive outpatient therapy and seemed to be more like the Dennis we knew and loved. We finally had reason for hope. Unfortunately, that hope was short lived.

Over the next year, Dennis turned into someone we barely recognized. He completely lost interest in the things he loved most: his family, his friends, his work, even his physical appearance. It was obvious that drinking had taken over his life. We were constantly smelling the cups he drank out of to see if we could detect alcohol. Even when caught red-handed, he would adamantly deny that he was drinking. It just did not make sense. How could this intelligent, proud, caring, disciplined man have fallen so far and why wasn’t he fighting to get better? We now know that what was happening in his brain didn’t allow him to make sound decisions or think clearly.

“We cannot continue to live like this”

The kids and I begged Dennis to go back into rehab but because he honestly believed he did not have a problem; our pleas fell on deaf ears. Olivia was especially relentless in trying to convince him and took it especially hard when he refused. I eventually gave Dennis the ultimatum of going back to rehab or moving out of our home. Dennis checked into a hotel.

“I was sure he heard me”

After seeing improvement in his behavior, I asked Dennis to join us for a family trip in December 2018. He was not comfortable traveling but did move back home over the holidays to look after the family dog, Louie. When we returned from vacation, Dennis was in bad shape, with abrasions all over his face. He claimed he fell over Louie’s leash on a walk. A neighbor told us they had found Dennis passed out, face down outside. We once again pleaded with Dennis to go back into rehab. Upon his refusal, I insisted that he move out of our home. We had gotten a glimmer of the old Dennis so forcing him to move out once again was devastating for all of us.

Weeks went by with periodic communication between us and Dennis. Unwilling to give up, Olivia reached out frequently to ask her dad to consider rehab. He continued to refuse.

On March 1, 2019, Dennis stopped by the house to pick up more clothes. While in the driveway, Dennis took a nasty fall that resulted in a trip to the emergency room. His blood alcohol level registered at nearly four times the legal limit.

When he was released from the hospital, I took him back to the hotel and Dennis shared plans of wanting to find new clients and get back to work. I was overjoyed to hear him talk like this and reminded him how good he was at his job. I assured him he could achieve so much if he could just stop drinking. It was a great conversation, and I was sure he had heard me. I left that day with more hope than I had felt in quite some time.

Just one week later, on March 8, Olivia came home from college for spring break with the intent of convincing her dad to go back into rehab. When she arrived at the hotel, she found Dennis face down and unresponsive. He was soon pronounced dead at age 51. The cause of death was chronic abuse of ethanol.

Relief and sadness

I had long desired for Dennis’ brain to be studied. After his death, we donated his brain to the UNITE Brain Bank. Researchers there confirmed what we had long suspected. They found he had Stage 3 (of 4) Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE).

The diagnosis brought many things to our family, namely an explanation for the inexplicable. We were relieved to be able to ascribe what had taken Dennis from the regimented and successful man he was into the state he was in before his death.

We also felt immense sorrow. No matter how hard he tried, Dennis was not going to be able to overcome what was happening in his brain. He lost a two-front war with addiction and a degenerative brain disease. Even if he had been able to conquer his drinking problem, Dennis was living with a disease that currently has no cure.

Don’t doubt yourself

We hope that by sharing Dennis’ story, we can repair some of the dignity he lost late in life and help his friends and former colleagues understand how CTE affected his mood, behavior, and cognition.

I hope to do for other wives what Lori McGregor did for me a decade ago.

It is critical to trust your instincts if you suspect your partner might have CTE. You also need to extend yourself to resources. You don’t have to fight this battle alone.

Do not doubt yourself. You’re seeing the symptoms and you probably know your spouse better than anyone. If you suspect CTE, reach out to available resources. CLF is here to help.

Nearly two years removed from Dennis’ passing, the kids and I are a galvanized unit. The hardship of seeing my kid’s father and my husband deteriorate before our eyes, and the shared trauma of losing Dennis has brought us closer than ever. I think Dennis would be incredibly proud of our children and how they have handled themselves through this tragedy. My hope is that in sharing our story, we can make the journey a bit easier for other families dealing with CTE.

We’re here for you if you have a loved one who is exhibiting signs of CTE. Please reach out to our HelpLine so a member of our team can provide individualized support for your situation.

Jimmy Fauser

Grant Feasel

Grant Feasel was a father, a brother, an 11-year NFL veteran and, now, a Legacy Donor. But who was Grant, really? His closest family members and friends offer their thoughts and memories below.

Grant Earl Feasel passed away peacefully in Fort Worth, Texas, on Sunday, July 15, 2012 after a lengthy illness.

Grant, a long-time resident of Colleyville, Texas, is survived by three children: sons, Sean and Spencer, and daughter, Sarah; mother, Patricia Feasel; sister, Linda (Feasel) Slayton; brother, Greg Feasel; children’s mother, Cyndy Feasel; plus numerous nieces, nephews and extended family. He was preceded in death by his father, DeWayne Feasel.

Born on June 28, 1960, in Barstow, California, Grant graduated from Barstow High School in 1978, lettering in football, wrestling and baseball. Upon graduation he was awarded a football scholarship to attend Abilene Christian University.

At ACU Grant was a four-year letterman and a three-year starter from 1979 to 1982. As a senior, he was named an Associated Press First-Team Division II All-American, First-Team All-Lone Star Conference and was voted the conference’s lineman of the year. A three-time academic all-conference choice and second team Academic All-American as a senior, he was selected to the ACU Sports Hall of Fame (Class of 1994-95) and LSC Team of the Decade for the 1980s. In 1997 he was selected to the NCAA Division II Team of the Quarter Century. He majored in pre-medicine and was accepted to Baylor University’s College of Medicine. He also was awarded the prestigious NCAA Post-Graduate Scholarship and the Annual Trustees Student Award for outstanding contribution and devotion to Abilene Christian University in 1983.

Drafted by the Baltimore Colts in the sixth round of the 1983 NFL draft, Grant played eleven seasons in the National Football League. He played for the Minnesota Vikings (1984-86) and the Seattle Seahawks (1987-93). He started for Seattle in the 1987 NFL playoffs, and also competed in the 1988 playoffs and played every offensive down of the sixteen-game season in 1989.

Grant and his family were long-time members of the Richland Hills Church of Christ. He was a beloved father, son and brother, plus a friend to many, many people.

The following tributes were written from his loving family and friends and shared during Grant’s memorial service.

From Spencer (son)

It seems like yesterday I was in elementary school having to tell the class what I wanted to be when I grew up. While the other kids said they wanted to be firemen and doctors, I remember standing up with confidence and saying, “When I grow up I want to be my dad.” Grant Earl Feasel was my hero, although he didn’t wear a cape and fight off villains. What he did do was teach not only me, but my brother Sean and my sister Sarah everything we know. I know there are hard times, and we all had some differences, but at the end of the day I wouldn’t have wanted to grow up any other way. I know I lost my dad when he was only fifty-two years of age and I was only eighteen, but I know this has happened to make me the man and father I will someday be. I just hope that I can be half as great a father to my children as mine was to me for only a short eighteen years. And I will cherish those eighteen years with my father and look back on them for the rest of my life. My dad was the greatest father I could ever ask for. I love you so much, Dad. I’m sorry we had to say goodbye, but we will meet again one day in Heaven.

From Sarah (daughter)

Daddy,

I always struggled to find the right way to tell you how proud I am of you. The truth is that your heart has always been too beautiful for this world. You saw and felt things differently than everyone else and you saw beauty in a way no one else could. The greatest compliment I’ve ever received is Aunt Linda telling me I have the same heart as you. She also told me that you called her crying the day I was born because you were so happy. Growing up you taught me to love rock ‘n roll. I’ll never forget singing Led Zeppelin and Tom Petty at the top of our lungs driving down 635. You also taught me how to give and give selflessly. You gave so much and made sure no one ever knew about it. You taught me about grace and forgiveness because you continually forgave me. One of the last things you said to me is, “Remember the beach.” I will remember that, Daddy, and so much more. You gave us enough memories to last a lifetime. I’ll remember those memories when my children ask about you, and I’ll get to tell them the kind of man you were. I’ll tell them that because of who you were I will cherish every minute of this life and never take it for granted. I’m still so proud of you, Daddy, and I’ll never stop bragging on you. Saying thank you doesn’t seem like enough, but thank you for teaching me where to find the source of lasting strength. The way you loved Jesus was inspiring to everyone who knew you. You loved to worship Him and I know that’s what you’re doing right now. I’m so thankful to know Jesus holds you now and takes away your pain. I know you had many friends waiting for you in Heaven, and I know I’ll see you there one day. You deserve to be free, Daddy. I love you so much. Love always, Your Princess Sarah

From Sean (son)

As I sat down to write this, I found it so very difficult to come up with the right words to adequately describe my father and everything that he means to me. How could I possibly articulate my feelings for such a special person and the relationship that I had with him? How could I possibly translate my emotions into words that would allow me to paint a picture of what I feel inside my heart? My dad was so many things to so many people.

The first word that comes to mind when I think about my dad is “Hero”—I promise that Spencer and I did not compare notes as we were writing. I didn’t know that he said the same thing until I read his letter late last night. But I was not surprised, because my dad was a real-life hero, in every sense of the word, to me, Spencer, and many others. I cannot tell you how many people have reached out to me over the past few days just to let me know that my dad was their hero, because I lost count.

I have so many fond memories of my dad. I didn’t even know where to start when it came time for narrowing down what to share with you. My dad was my best buddy in the whole world when I was growing up. I looked forward to the football offseason each year like most children anxiously await Christmas morning, because offseason meant that I had my dad all to myself for a few months. And we made sure to take full advantage of the time together. I hope this doesn’t upset any of his former teammates who are here today, but I sure wasn’t upset when they failed to make the playoffs!

We did all kinds of cool stuff during the offseason—it seemed like he had something planned almost every day. We would play golf, go to the pool, build stuff in the garage. We made all kinds of memories that I will cherish forever, but our favorite activity back then was to ride dirt bikes together. I remember one time we loaded up our bikes and went to check out a new track that we had never been to before. We started off cruising around, and we explored some trails for a little while. But I quickly grew tired of that and challenged him to a race. We picked out a tree way off in the distance as the finish line. I could tell he was pretty confident that he was going to beat me because he had a much bigger and faster motorcycle, but he didn’t know that I had a plan. The route to the finish line was a big half circle around a field covered with waist-high brush. I was going to let him get ahead of me and then cut through the brush field straight to the finish line. My plan was working perfectly, right up until the point that I ran into an old, dried-up creek bed that was about eight feet deep and four feet wide, going way too fast to stop. It was an ugly crash that ended with my bike on top of me in the bottom of that creek bed. A few seconds later my dad pulled up and took his helmet off, and once he saw that I was okay, he started laughing so hard that he couldn’t even talk. I was curious as to what he thought was so funny because I sure didn’t see the humor in my current situation! He helped me to my feet, and once he gathered himself he said, “I was watching you tear across that field at top speed and all of a sudden you just vanished into thin air! I thought you disappeared into the Bermuda Triangle!” When I heard that, I started cracking up. Once we finally stopped laughing, he pulled me and my bike up out of that creek bed and said, “Well, Sean, I bet that will teach you not to cut any corners in life.” And you better believe I remembered that lesson after I learned it the hard way.

As a small child I guess I just assumed that all fathers were as great as mine, but it became very clear that my dad was the coolest one day in the First Grade. That day was career day. Evidently all of the other dads did not play football for a living, and being a pro-football player was the coolest job ever—that was news to me! If I remember correctly, we had a policeman, a lawyer, a preacher, and a doctor show up as well. All very noble professions, but the football player stole the show that day! Needless to say, I never had anyone approach me with the “my dad could beat up your dad” argument.

Though my dad was so much more than just a football player, there is no denying that the game was a big part of his life. You are all aware of what he accomplished as a player, but I want you all to know that his accomplishments on the football field extended far beyond the end of his playing days. He most certainly passed his competitive drive and his love for the game down to me. And he used the game of football as a vessel to break through and teach me and many other young men that he had the opportunity to coach throughout the years the important lessons about the game of life. The life lessons that he taught me on the football field molded me into the man that I am today, and I am confident that many others in this room would tell you the exact same thing. He used the game to help build our character, to teach us toughness, sacrifice, resilience, dedication, teamwork, and diligence, just to name a few.

I recall a conversation that we had very early on in my playing days just like it was yesterday. He said, “Sean, the most important lesson that you’ll learn out here is how to get back up after you have been knocked down, again and again.” Although I did not grasp the depth of that statement at the time he said it, I really took it to heart, and it has been applicable to my life many times over the years. But, Dad, this knockdown is unlike any other that I have experienced. I know it isn’t going to be easy, but I promise you that I am going to get back up, because that is what you taught me to do.

Quite a few of my old teammates have contacted me over the past few days to let me know how much it meant to them that my dad sacrificed his time for all of those years to be a volunteer coach, and what an impact that time had on their lives. It brought back so many good memories. Some of the stories that came up earlier this week brought me to laughter and put a smile on my face at a time when I wasn’t sure if I would ever smile again.

My dad gave us pointers, encouragement, constructive criticism—though there were a few instances when I questioned the constructive part—and taught us many tricks of the trade that only an old NFL vet would know. He gave us a clear advantage over the competition on the gridiron. But more importantly he always made sure to relate what he was teaching us on the football field to what we were going to encounter in the real world, and he made sure that we knew how to apply the same principles to face the challenges and climb the obstacles of life.

Not only did my dad use coaching as an outreach ministry, he also used the platform built by what he accomplished on the football field to make a difference by reaching into the lives of many others and touching their hearts—hearts that he may not have had an opportunity to reach otherwise. Looking back, it was such a privilege to be able to tag along with him, and have a front row seat on many occasions to watch as God used my dad to inspire others. I remember going with him one time when he went to speak at a men’s retreat back when I was just a little guy. It was truly a testament to the character of my father to see firsthand just how influential of a man that he really was, and to watch him use his ability to influence to spread the message about his Lord and Savior. My dad knew that his status as a football player gave him the gift of influence, and this was not a responsibility that he took lightly. And I am so very proud to tell you that he used that gift to further the kingdom of God every single time that he had an opportunity. I have had several people tell me that they would not be a part of the body of Christ today if it were not for my dad, and I guarantee you that he was far more proud of that than any of the rewards he ever received for playing football.

My dad used to tell me, “Sean, you need to make sure that you are always conscious of how you conduct yourself because you are a leader, and you have the ability to influence others. That means you aren’t just responsible for your own actions—you bear some responsibility for the actions of others.” He would say, “People are going to look up to you because you are tall, and you need to be aware of that.”

My response to that was, “Well, Dad, I guess I don’t have anything to worry about as long as I am standing next to you.”

He quickly fired back with, “You would be just as tall as I am if you weren’t so bow-legged!”

Jeff Kemp, a long-time friend and teammate of my dad’s, recently described him by saying, “Grant was the quintessential sacrificial warrior. He wrapped himself up in the duty to clear the way for and to protect his teammates. He took his job so seriously. Our families grew up together, and Grant deeply loved his family. He had a great sense of humor, but never during the heat of battle.”

Right after I read Jeff’s tribute it became clear to me just how accurate his description of my father really was. I sat down at my dad’s desk to start preparing what I was going to say today, and I came across a folder full of loose pieces of paper and note cards that my dad had kept throughout the years. The first piece of paper I pulled out said, “Vikings Training Camp Goals—1986” across the top, and the goals that he had listed on that piece of notebook paper were:

- One day at a time, one play at a time

- Be aggressive

- Be a starter

- Do it for Cyndy and the baby—Sean will be proud of my effort

- Don’t take the easy way out; no excuses

- Make every practice count

- Be an All-Pro and win the Super Bowl

- Earn respect and dominate

- Don’t get beat at 1-on-1 pass pro

- Be a professional

- Be Mr. Consistent

- Remember who you are playing for and why. Because you are in a good position God expects more from you

- Just play my game, be positive and remember that I’m the man

The next piece of paper that I pulled out of that folder was an old newspaper article from right after my dad retired. At the end of the article there was a copy of a telegram that was sent to my dad on the day of his retirement party by Tom Flores who was the coach and GM of the Seahawks at the time. The telegram said, “On this evening commemorating your NFL career. In your 7 seasons with the Seattle Seahawks you conducted yourself as the consummate professional on and off the field with both class and dignity. I know I can speak for all the coaches, your teammates, our staff and friends in saying you will be missed on the field, but you will always be part of our family.”

If I could send my dad a telegram (or maybe an email) on the day of this retirement party, I would say to him, “Dad, I am so proud of you, and I love you. It was such an honor and a blessing to be your son. I am so thankful for everything you have ever done for me. You provided me with more opportunities and advantages in life than most could ever dream of. And you taught me so much. I will do everything in my power to continue your legacy. You will be greatly missed down here, but you will always be my daddy and my hero.”

From Greg (brother)

Wow, where do I start today? I apologize up front. There is no playbook for this. First, our family is grateful, honored, humbled, and blown away by the love and support. Secondly, it’s great to see everyone. We want to thank you for coming today to honor Grant and by honoring him our family and you honor God. We want you to know how important all of you are to us. Our lives have truly been blessed because of you.

I’m so sorry for all of us. It needs to be said upfront, the last few years have been very difficult for Grant and very difficult for our family. We are so sorry. We also need to send out a special thank you, to the ones who went above on beyond the call of duty for Grant. You stepped up for him—we know there was many times when it was very difficult. I will not even try to say the names or list what you did for him. It was family, friends, co-workers, the people Valley Hope, Spring Wood, Heartland, HEB, the Hospice and his work (Fuji Film). You know who you are, we know who you are, Grant knows who you are and more importantly God knows who you are. You are remarkable people. You set the bar for the Golden Rule. You did it out of respect and love. From the bottom of our hearts we thank you for loving Grant.

His life was not supposed to end this way. He had it all—a great heart, great presences, brains, good looks, strong work ethic. Everyone loved him and he loved them back. Just about every gift you could describe he had. At the beginning of the movie “The Natural” the father is talking to a young Roy Hobbs, and he tells his son “A gift is not enough. If you rely on your gifts alone you will fail.”

We want you to know we are as shocked as you are that this could happen to Grant. We are asking the same questions. How? Why? What happened? How does a guy from 1291 West Buena Vista, in Barstow, overcome every obstacle thrown in his path, not beat this one? The answer is we don’t know and may never know. But, that not why we are here today. We are here to remember Grant, celebrate his life, and celebrate God’s gift of grace (getting what we don’t deserve) and gift of eternal life.

A very dear friend of mine, Bo Mitchell. Called me when dad passed away to provide some words of encouragement “Death does not determine (God does) the direction you go but fixes into place for all time the direction you have already chosen to go (while you were still alive).”

Grant chose Christ (you can book it), and as Christian’s we don’t pass from life to death. We pass from life to life. None of us, including Grant were happy about his condition at the end. Today we can have heavy hearts, we can cry, we can get angry, we can be confused. But, we can also have joy. We can have hope and peace because we will see him again in Heaven. As Christians we know God’s love is unconditional and God’s grace unconditional. That’s His promise! We also know God has a special place for Grant because he did make that decision. We also know Christ died on that cross for all of us.

In Isaiah we read, “But He was pierced for our transgressions, He was crushed for our iniquities; the punishment that brought us peace was on Him, and by His wounds we are healed. We all, like sheep, have gone astray, each of us has turned to our own way; and the Lord has laid on him the iniquity of us all.”

Grant stumbled. He knew it. He said it with his lips. He said it with his eyes. It’s said, “The eyes are the windows to the soul”—and you could see it in his eyes. He knew it. Job said, “For the thing which I greatly feared has come upon me.” Grant gave up a sack. His gifts were not enough to overcome this adversity.

Grant and I were big Rocky Balboa fans growing up. I remember the two of us driving the Red Sled (1952 GMC pickup) to San Bernardino to see the first Rocky movie in (1976). In Rocky IV it’s Rocky vs. Drago, David vs. Goliath. Drago was billed as unbeatable, invincible, the perfect athlete, the perfect fighter. Old school vs. new school, low tech workouts vs. high tech workouts. As always, Rocky had no chance to win. The fight starts; he gets knocked around. Then, out of nowhere Rocky cuts Drago. Rocky’s manager yells, “You see, you see—he’s not a machine. He’s just a man.” At times, we all saw Grant as bigger than life and maybe invincible. Well, Grant was just a man! On any given play, any moment in sports, it’s filled with imperfections. We all are just human. We are not perfect. But by the grace of God and the sacrifice of His Son, Jesus, we can leave our imperfections at the foot of the cross.

Everyone knows our family loves the beach. You have to love the ocean after growing up in Barstow where the summer temps are always over 115 degrees. We have all watched little kids play in the surf, running back as forth as the waves come in and go out. I will never forget the first time our daughter, Zoie, got blasted by a wave (yes, on my watch). She would have a smile on her face from ear to ear as the waves chased her to shore. She would turn around and chase the water back out. Each time she would gain more confidence and go farther out. We all know what happened next—the big one hit! Arms, legs, hair everywhere as she tumbled back to shore—tears, nose running, covered in sand. Zoie did not plan for that to happen. She did not see it coming, but it did. I think that, in some strange way, is what happened to Grant. He did not see it coming and got too far out and could not get back to shore. Praise God for His grace, and for His promise—that death does not determine the direction we go, He does.

We all knew Grant was special at a very early age. He was always ready for the game, ready for the test, ready for any task both mentally and physically. I remember he started running a bank out of a red metal ammo box. He might have been 8 years old. And, yes, he had the only key— who knew?! Mom often went to him for milk money. He was always happy to help out. But, he always made sure Mom paid him back. And, Linda, I think we can assume Grant finally has forgiven you for not paying back that $1 you took from the bank and never paid back. At 10 it was clear that he knew how to lead, and we saw it in pee wee football (the Marauder’s). At 12 we saw his compassion and his love for others and his love for God. As a camper at TANDA Church Camp he was named the Best Boy Camper 1974. He always knew what he wanted and was gladly willing to pay the price, or he was willing to walk away. That conviction, that mind-set, continued into college. He told the football coaches he would come to ACU but wanted to be a pre-med student and he would not miss the afternoon labs or his studies. On most nights he was gone from dorm room well past curfew. Everyone knew he was in the science building, studying.

Wednesday morning at the gym as I turned on my iPad/Netflix, I searched for a movie to veg out. Brian’s Song popped up. For you under forty, it’s a true story—a beautiful story about two Chicago Bears running backs, their lives, their unique/special relationship and death in 1971. I quickly flashed back to Morris Dorm at ACU—I can picture that dorm room full of football players like it was yesterday. I was telling Hal Wasson this story. He said I had the wrong room. I’m right. Hal is wrong. Then we argued which floor it was. Picture this, the lights turned off. Each of us holding a pillow to hide the fact that we were crying. Anyway, the scene that sticks out is at the end of the movie. Brian Piccolo and Gale Sayers are running through the park. The voice-over is the coach, George Halas. “Brian died of cancer at the age of 26. He left a great many loving friends and family who miss him and think of him often. But when they think of him, it’s not how died that they remember. But rather how he lived, how he did live!

Today, let’s remember how Grant lived.

A few of Grant’s friends also remember and share some thoughts:

“The first time I saw Grant, I thought he looked like a basketball player but found out soon enough how quick and aggressive he was in practice and explosive he was in games. I remember he always had time to listen to me no matter what the circumstances and encourage me when things were tough. He taught me how to surf when we were playing the University of Hawaii. But the most important experience that has lasted a lifetime for me was and is his example of being a Christian. I am thankful to Grant and his family for taking an interest in me as a young, lost individual and giving me some direction through Christ Jesus. After becoming a Christian, Grant was one of the first people to congratulate me and encourage me.

“And if was lucky I might get a bite of his mother’s famous cinnamon rolls.

“He sent me a care package during Desert Shield/Desert Storm which had the Seattle Seahawks return address on the box. It was fun watching the reaction of some of my fellow Marines as I opened the package. He was always a positive influence on my life. I love you Grant—you will always be in my heart.

“I love you, brother—David Rankin”

“Today I’m thinking of when we were boys in Barstow. Grant, you had a sense of humor, perfect timing—you were funny. Thanks for all the laughs. So on this day of death and sorrow, I choose to think upon life and laughter. Through faith I know Grant is alive and well, happy in his new body, finding humor in it all.

“Your friend, Mark Korn”

“When I first met Grant on my recruiting visit to ACU, all I knew was, ‘This guy is big!’ But it didn’t take long to get to know Grant and find there was so much more to him than size and athletic ability.

“Grant was a leader. He was a great football player—and going against him in practice every day made me a better player too. He led by example—not a lot of talk, but hard work and commitment. He pushed himself to be the best, and others followed his example.

“Grant was smart. I was always impressed that he was Pre-Med and played football. Not only was it difficult, but he excelled—I remember his GPA being in the 3.5-3.6 range—leaving practice early or coming late because of a chemistry or bio lab.

“Grant had a great sense of humor. He loved to laugh. He was always cracking jokes and making fun of himself and his teammates.

“Grant had a great heart. If there was one thing I knew about Grant, it was that he cared for people. It was obvious in the way he interacted with others—he could be funny, have a great time joking around, but then serious about the important things.

“He loved God. I know Grant had deep faith. It was obvious that his life didn’t depend on his circumstances to make him happy.”

Dan Niederhofer

“Dedicated. Focused. Competitive. Leader. Caring. The list could go on and on when you are describing Grant. From the moment I met Grant in August of 1978 at ACU, I always knew that I had a great friend, and over the four years that we lived together in Morris Hall, we shared so many experiences together that I will cherish for the rest of my life. Over the years as our careers and families took us on different paths, when we got together we would always reminisce about those special times we spent together so many years ago. The one thing that always struck me about Grant was how dedicated and focused he was on the task at hand. Preparation was always such an essential part of his life. Whether it was studying for a test, or preparing for an upcoming opponent, or even leading singing and delivering the message at Hamby Church of Christ, he took great pride in preparing for that special moment. As we all gather today to remember our great friend and brother, let us not weep in sorrow for our loss, but let us rejoice in the fact that Grant is at the side of Christ, and as we speak, he is preparing for all of us a place when we meet again.”

Kris Hansen

“As I reflect upon my time with Grant, I am reminded of the Biblical characters David and Goliath. When an offense breaks the huddle, the first to leave and the first person the opposing team sees is the center. Just as the Israelites first saw Goliath, the defense would first see Grant approaching the line of scrimmage. A towering and impressive site that we hoped would reflect the upcoming offensive attack. He gave confidence to his teammates because of his size and ability. Yet, like King David who led his soldiers in battle, Grant’s teammates knew he would perform his assignment correctly. They knew he would make the correct calls at the line. With his shepherd-like spirit he would encourage and challenge his teammates in the huddle, on the sideline, and in practice. His teammates also knew Grant gave God the glory for his talents and ability.

“My last visual recollection of Grant was a few years ago when he was visiting one Sunday at Southern Hills. I saw him from across the foyer, head and shoulders above the others around him, and only spoke with him briefly because so many wanted to visit with him. But what I remember most as I saw him across the room was that giant smile of his, a smile he seemed to always have. His smile was a reflection of the spirit in his heart—a man after God’s own heart. May God’s smile be upon Grant and his loved ones this day.”

Don Harrison

“Grant’s life cannot be summed up in a short paragraph. But to those of us who knew him well and loved him dearly, here are some words that begin to describe who Grant was:

“A neat freak

“A huge, loud laugh that would make you want to laugh

“A California free spirit

“Driven, disciplined

“Always looking in the mirror at himself

“Self-conscious

“Great rhythm

“A heart for the little guy

“Referred to everyone as ‘Dude!’—before dude became cool

“Hair always perfect

“Huge Neil Young fan

“Always offering advice—even when you weren’t looking for any

“Extremely loyal, trustworthy

“Would never quit talking about his family

“Tender and compassionate

“An irritatingly slow and picky eater, sometimes refusing to go into a restaurant he didn’t like, rather sitting outside while we ate

“A funny, sometimes twisted sense of humor

“An overachiever. But out of the many awards he won, the one he was most proud of and never let us hear the end of?? “Del Taco Employee-of-the-Month”—three straight months in a row in high school! [Well, DeWayne you have that wrong—it was really Naugle’s.]

“Grant would laugh with other people but never at their expense.

“Tenderhearted, a pleaser

“An early riser and the first to go to bed

“Shamelessly used his large size to get to ride shotgun wherever we were traveling, and if he ever did end up in the back seat, would repeatedly complain to the point he would wear us out, and we would put him in the front seat just to shut him up.

“He would sweat more profusely than anyone we’ve ever known.

“He was moral and decent.

“A deep thinker, a closet intellectual

“A perfectionist

“Would let you know how he felt or what he was thinking just by giving a certain look

“Had a secret ambition to be a rock star

“Extremely competitive

“Loved telling stories and was a good storyteller, even if he told you the same story one hundred times

“Above all, Grant was peacemaker, a unifier, a lover—not a fighter

“To summarize the Grant we knew, we can say Grant simply ‘got it,’ and we loved him for it.”

-DeWayne Hall