With memories of dad in tow, Jesuit football player bids touching farewell to the sport

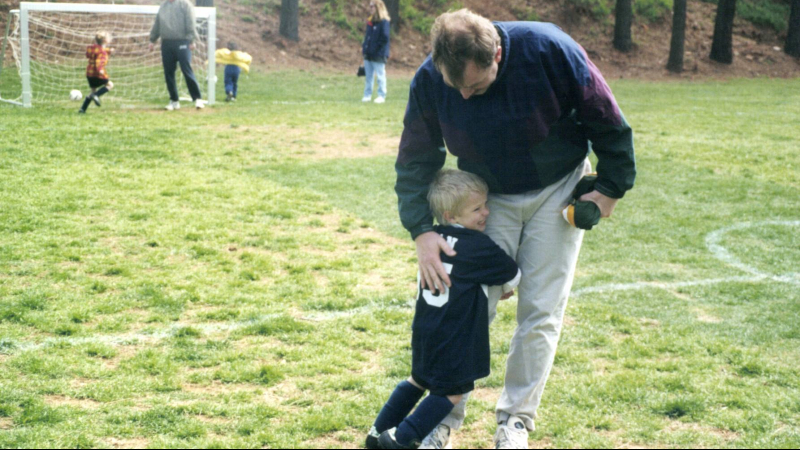

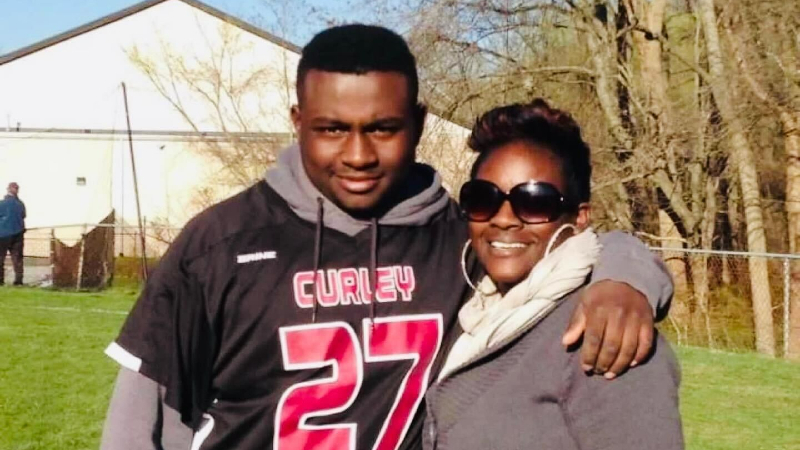

Jesuit High Schools Jacob Hall has had numerous injuries that have sidelined him at the end of his high school football career. His father, Jesuit teacher and coach Justin Hall, suffered from chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE, caused by concussions during his football career which including college at Notre Dame. The neurodegenerative disease culminated in his suicide four years ago. Moments before their game against Vista del Lago on Saturday, April 17, 2021, Jake shows a table that honors his father on campus at Jesuit High School in Carmichael. Xavier Mascareñas [email protected]

Jesuit High Schools Jacob Hall has had numerous injuries that have sidelined him at the end of his high school football career. His father, Jesuit teacher and coach Justin Hall, suffered from chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE, caused by concussions during his football career which including college at Notre Dame. The neurodegenerative disease culminated in his suicide four years ago. Moments before their game against Vista del Lago on Saturday, April 17, 2021, Jake shows a table that honors his father on campus at Jesuit High School in Carmichael. Xavier Mascareñas [email protected]

Jake Hall stops by the table most every day, to reflect, to wonder what was and what might have been.

The Jesuit High School senior will also look to the heavens and speak in spirit to the driving force in his life. It’s the silence of no response that pains Hall the most. The nameplate fixed to the campus structure is a memorial marker for his father Justin Hall, a beloved teacher and football coach at the school for nearly 20 years. He died in 2017.

Hall is closing in fast on graduation and the start of the rest of his life. It will be a journey that will no longer include the highs and rigors of his favorite sport. That adjustment is difficult to accept. Hall was deemed as Jesuit’s best player by Marauders coach Marlon Blanton, and one of the school’s top scholars with a 4.3 grade-point average. He is also perhaps Jesuit’s most courageously strong individual.

“What an incredible person Jake Hall is, just wow,” said Jesuit’s longtime football public address announcer, Tim Fleming.

“This season,” Hall said in soft tones, “has been the hardest, the most painful, but also in some ways the most rewarding. I know I’ll never play football again, but I know I have teammates and coaches who care.”

The spring football campaign started with the 6-foot, 170-pound Hall bounding into the mix with visions of touchdown receptions, crushing tackles on defense and playing small-college ball in Southern California. The season was marked by searing agony, of surgically repaired shoulders getting torn apart in a game against chief rival Christian Brothers. His screams on that cool March 26 night in Oak Park reverberated in a Christian Brothers stadium half full due to the pandemic.

On April 17, Hall was back in uniform, incredibly, but he was a shell of his playing self. He caught the ball on the first play from scrimmage against Vista del Lago on the Marauders’ home turf and hustled out of bounds. He had to get out of harm’s way, his shoulders too battered to do much more. The play was by design. Coaches from both sides agreed to this move of sportsmanship and closure. Some two hours later, the contest ended with Hall taking a knee for the Marauders in victory formation to cap a 56-42 triumph. He was embraced by coaches and teammates, and later family, a memorable Senior Day if there ever was one.

Hall said this all comforted him, a good thing, because he cannot escape the hurt. His heart hurts. His surgically repaired shoulders hurt. His pride hurts. He visited that memorial table an hour before his football grand finale, wearing his familiar bright red No. 29 jersey, relieved that his body has waved the white flag, but saddened also that he cannot continue his father’s college legacy.

“I’m honored, touched, and proud that my dad had that sort of impact on people, and that people miss him, because I sure know that I do,” Hall said, sitting at that table. “I think about him every day, at every game, on every play. He’s the reason I love this game. He continues to give me strength. Dad went through his own injuries and pain, and it was something years later that he really struggled with. That’s the saddest part. We couldn’t help him or save him.”

Losing a coach/father/mentor

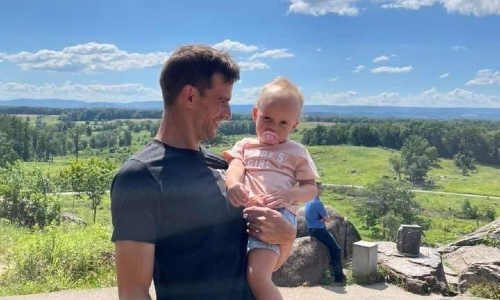

Coach Hall died by suicide on Nov. 27, 2017, shortly after coaching his oldest son in junior varsity football. Jake Hall believes his ailing father held on long enough to be able to coach him before he lost his will to live.

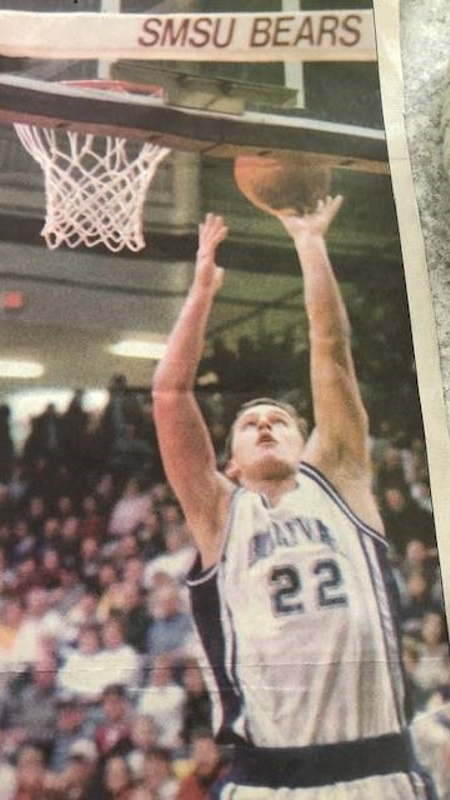

Coach Hall helped anchor two state championship teams in high school in football-mad Texas and grew into a mountain of a man at 6-foot-5 and nearly 300 pounds. He met Jen at Notre Dame and they married after relocating to Sacramento. She worked in the football office, handwriting letters to recruits.

Coach Hall told Jen before his death that he was worried about his own behavior, his irrational thinking. Their final six months together were not easy. He was emotional when he told her, “I don’t know what’s wrong with me.” He feared he was slowed by countless football practice and game collisions — concussions — as a Notre Dame lineman, a run that included the 1988 national championship under coach Lou Holtz.

Coach Hall told Jen he wanted to have his brain studied after he died at Boston University for Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy, a degenerative brain disease found in athletes with repeated blows to the head. Coach Hall lived long enough to see his son earn team MVP honors on the junior varsity. He was found days later in the family garage, before Hall and his two younger siblings, Caleb and Abby, got home from school.

As traumatic as it was, Jen said it would have been a great deal worse had the kids found him first.

“We learned that Justin had Stage 3 CTE, really bad, and the fact that Justin was even functioning at all was amazing,” Jen Hall said. “I was in Seattle for a work trip when I got a call from Jesuit that Justin hadn’t come to school for work. I knew something was terribly wrong. At that moment, you know life is changing for our family, and you shift into survival mode: get to the kids, take care of them, hug them, love them — and do the best to explain it to them.”

She paused and added, “Jake as the oldest has been amazing. He’s handled it so well, as have his siblings. Proud of all of them. Jake has been outspoken about mental health, and we wonder and wish his dad had done things differently. But his brain was damaged. It’s frustrating and it hurts because we want things to be fixed.”

Jen Hall speaks openly about CTE. She doesn’t avoid the topic with family or friends because she understands the CTE toll families.

“We don’t know how to fix CTE without not playing sports at all, but we know what leads to it — blows to the head,” she said. “CTE hurts more than just the player. It hurts everyone who knows and loves that player.”

Letting him play

Jen was worried about Jake playing football. Concussions happen in this sport, certainly, and her son never played cautiously or in slow motion. He was a full-bore. player His father coached him to compete like that.

Imagine, then, Jen’s anguish when she watched her son writhe in pain against Christian Brothers. He landed awkwardly on his left shoulder, and the force tore through seven titanium anchors that held the shoulder together from previous injuries. As Jen stood stunned in the stands, hands on her face and her eyes welling with tears, she was most moved by teammates and coaches rushing to console and comfort her boy. She also didn’t want to be the sort of mom to scale the fence to rush to his aid.

“It was the most painful moment of my life, because it made me think of my dad, that loss, not having him when I needed him, and then knowing I was badly hurt,” Jake Hall said. “I was screaming because I knew football was over for me, that it was finally over. It all hit me at once. My shoulder had already been dislocated 15 times in high school. Just too much. It just can’t handle it any more of this game. My body was telling me to give it up, and that’s hard because you want to play forever.”

Hall caught his breath and added, “I was lying there on that field, my mind a blur. I’m thinking of what my dad might say to me, and then coach Blanton grabs my head, looks me in the eye and tells me, ‘It’s OK!’ That was a special moment. He was right. It was going to be OK. I needed to hear that. All things considered, I was OK.”

Jen views football differently now.

“I used to watch football for fun,” she said. “Now I watch to make sure everyone is standing up after plays. That’s the evolution of a football mom. When Jake went down against Christian Brothers, it became surreal. Oh, he’s not hurt. Then you realize it’s your son, and you hear him in horrible agony, and you know he’s there playing for his dad. It wasn’t just a game. His career was ending. It was surreal and sad.”

The return

With the blessing of his family doctor and his mother and coaches, Hall talked his way back into playing one final set of downs, to exit the sport on his terms. No tackling, no blocking allowed.

Jen watched from the bleachers, as she always has. This time, the tears were for the end of a playing era. She said she was at peace knowing her son was able to walk away from the sport before it dictated the terms. Blanton was emotional in talking about it.

“Jake’s a Marauder through and through,” he said. “He means a lot to the school of Jesuit. He’s more than a football player. We wanted to honor him any way that we could in this final game.”

Jen Hall said in her home, her three kids talk openly about their father. They don’t hide any sense of shame. Brain trauma happens, and suicides happen, sadly.

“I never wanted to pretend that their dad didn’t exist,” Jen said. “Sometimes, suicide is so painful to talk about, to deal with it. We let it out. We talk about it in our house.”

She added, “There was a lot of good about Justin. I was always so proud of him as a coach, for making such a difference for so many kids.”

After a moment, she added on any perception that her husband was selfish in taking his own life, “When someone has that sort of brain damage, they’re not in their right mind and their brain is simply not functioning properly. For anyone to judge a man like Justin for what he went through and did is highly inappropriate. I’m no mom of the year winner, but I do my best, and they’re thriving, happy kids. And we’ve learned a lot, that life really is a journey and it’s how you handle things.”

Making dad proud

Jen said she was touched members of Notre Dame’s 1988 title team attended Justin’s funeral services in 2017. Players hugged her and comforted her and the kids. Younger son Caleb is a 15-year-old freshman who wore his father’s old No. 73 this spring season. He is a large kid at 6-foot-4, following in his father’s size. Jen will not prevent Caleb from playing in the trenches, never mind the dangers. Older brother Hall is writing a research paper for school on CTE. He said the rewards of football still outweigh the pain of the sport.

“You have brothers and memories to last a lifetime,” Hall said. “Football is about life, and I’ve had a good one.”

He added, “We know that football is much safer than it’s ever been with concussions. My brother knows this. I tell him to be aggressive in football but to be smart and safe. It’s OK to leave the game if you feel like you’ve taken a shot to the head, or to avoid someone going for your head. That doesn’t make you a coward. It makes you safe and smart. I’m proud of him. Dad would be proud of him.”

Hall said the table bearing his father’s name was a surprise donation from his best friend, Ronan Brothers, through an Eagle Scout project. Hall recalled a moving conversation with his father, weeks before his death.

“He sat me down and told me that if anything were to ever happen to him, that I needed to take care of mom and the younger siblings, to be there for them, to be strong for them and for me,” Hall said. “I thought maybe he was talking about if he were in a car accident or something. I didn’t understand the depth and meaning of what he was saying, but I do now. I’m grateful for the time we had with dad, our special bond, and I will always be inspired to do the best, to be the best I can be, and I will. I’ll make him proud.”

Jesuit High Schools Jacob Hall has had numerous injuries that have sidelined him at the end of his high school football career. His father, Jesuit teacher and coach Justin Hall, suffered from chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE, caused by concussions during his football career which including college at Notre Dame. The neurodegenerative disease culminated in his suicide four years ago. Moments before their game against Vista del Lago on Saturday, April 17, 2021, Jake shows a table that honors his father on campus at Jesuit High School in Carmichael. Xavier Mascareñas

Jesuit High Schools Jacob Hall has had numerous injuries that have sidelined him at the end of his high school football career. His father, Jesuit teacher and coach Justin Hall, suffered from chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE, caused by concussions during his football career which including college at Notre Dame. The neurodegenerative disease culminated in his suicide four years ago. Moments before their game against Vista del Lago on Saturday, April 17, 2021, Jake shows a table that honors his father on campus at Jesuit High School in Carmichael. Xavier Mascareñas