Tyler Hedtke

Warning: This story contains mentions of suicide that may be triggering to some readers.

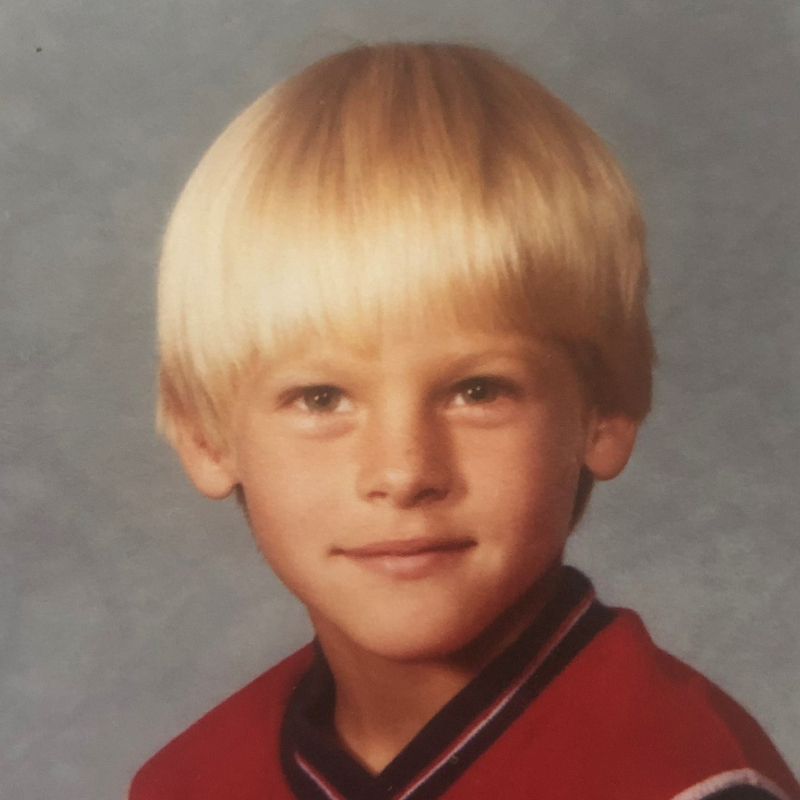

Tyler was his parents’ firstborn, deeply-beloved child. He was a sweet, curious boy and hilarious big brother. He was a full-tilt football player and a lifelong, committed friend. He graduated from high school in 2013, earned an associate’s degree in automotive technology, and had a passion for fast cars, his favorite being BMWs.

Tyler held a universal curiosity for life’s adventures, meaning, and beyond. He loved deeply and tried hard, fully expecting to master every skill on his first attempt. His teen years and adulthood were complicated by addiction and the search for contentment. He saw himself as a leaf on a river and encouraged us to resist trying to control the river. He helped and was helped by many people.

Tyler died by suicide; choosing to be done struggling to find peace. We wish that he could have realized his greatness…maybe he has.

Tyler’s parents suspected he might have CTE, so his brain was donated to the UNITE Brain Bank for research. The results showed that he did NOT have CTE. One more great thing about Boston University: other reputable organizations, doing research on mental illness and/or addiction, will be able to study his brain, too.

“Today well-lived makes every yesterday a dream of happiness and every tomorrow a vision of hope. Look well therefore to this day.”

~Francis Gray

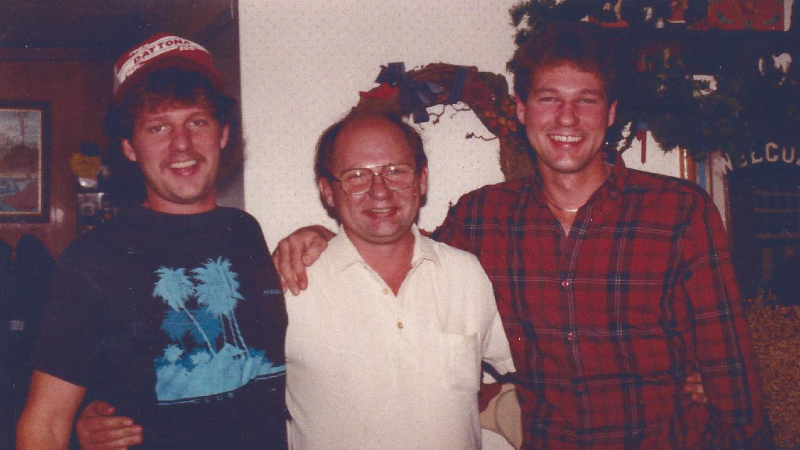

Scott Heisler

Warning: This story contains mentions of suicide and may be triggering to some readers.

Tenacious: not readily relinquishing a position, principle, or course of action; determined.

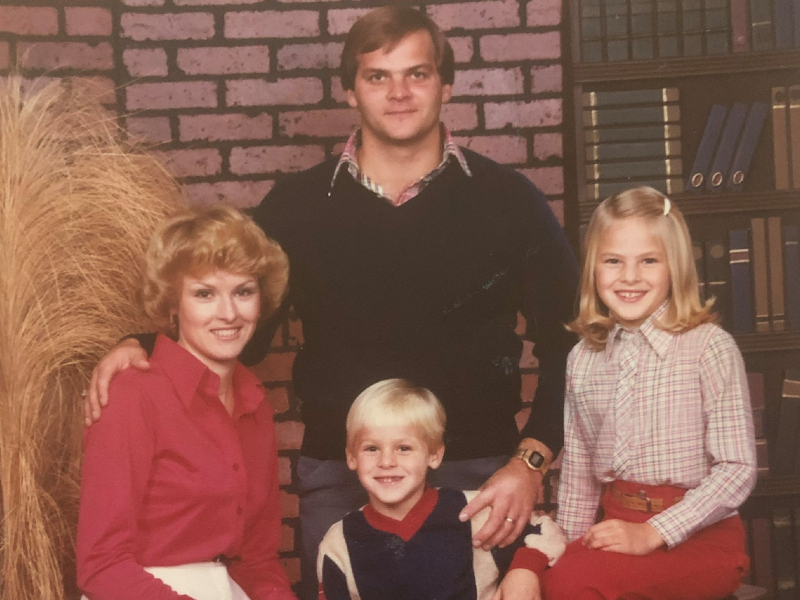

My brother Scott was nothing if not tenacious. It’s the word my mom used most, when describing his personality. Determined for sure, and always with an ornery little twinkle in his eye!

As a small child Scott was an early walker and then an early climber – of all things. When he was only two years old, he was caught halfway up a light pole during one of our dad’s slow-pitch softball games. The umpire stopped the game and asked whose kid was up there. Can you even imagine?

He also learned to ride his bike early, at just three and a half. He could ride it but couldn’t stop. A problem he solved by simply putting his feet down, which is why he always had bruises on the back of his calves… from the bike pedals hitting them each time he “stopped.”

Scott had lots of energy as a child. Our mom had him tested for ADHD because of his hyperactivity, impulsivity, and inattention. During his testing though, he was perfectly behaved and played nicely with his toy cars the entire time. Almost as if he knew exactly what to do to get out of the appointment. Since we didn’t have the information or help back then that we now have for these types of disorders, my brother was never officially diagnosed.

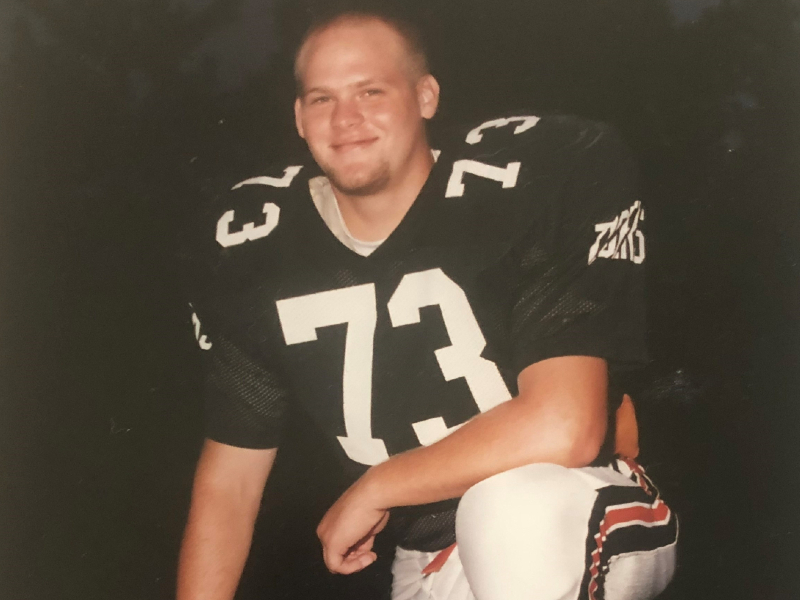

Scott was also very athletic, involved in several sports growing up. He started out playing baseball, like most young boys at that time. We moved from our small town of Oskaloosa, IA, to Des Moines, IA, before Scott’s 4th grade year. That fall he started flag football with our dad as his coach. He found his sport of choice! He would also try out wrestling and track along the way, but football was his constant, his passion.

He progressed to playing tackle football in 6th grade. We just didn’t know then; all we know now.

Scott played tackle football for the Des Moines Catholic League from grades 6-8. He then played four years for his high school team, the West Des Moines Valley Tigers. He made varsity from grades 10-12, making 1st Team All-State Defense as a senior. There were never any reported concussions during those years, but Scott played hard, giving 100 percent on the field and at practice. He loved the sound of helmets cracking, loved “hitting hard.” Again, we simply didn’t have the knowledge in the early ‘90s that we have now. If only we’d known.

After giving college a try for one semester, Scott decided to enlist in the Marine Corps. He did so without much discussion with our parents, typical of him because he could be very impulsive. I think he also liked the idea of being a Marine and what they stand for: honor, courage, and commitment. He saw them as the best and the strongest of all the lines of service.

Our dad recalls Scott’s four years in the Marines:

“Scott enlisted in the Marine Corps in December of 1994. He went to basic training in San Diego at the MCRD for three months. While in bootcamp he was exposed to many instances of blows to the head and entire body during self-defense and combat training.”

His permanent station was at Camp Pendleton in California. His MOS was a TOW rocket operator (tank assault team) which obviously included being around explosions, concussive blasts, and other explosives.

Scott was recruited to be a member of the Marine Regiment football team. He played three years and made All Base team twice. I would compare the level of competition to be similar to NCAA Division II but in much more “aggressive manner.”

I know for a brief period he and some teammates were using PEDs, obtained from across the border in Mexico.

Scott was the victim of an attack by another Marine while on duty in Arizona, patrolling the border. The fellow Marine struck Scott in the back of the head with a lead pipe. He spent at least one night in the hospital after this attack.

My brother completed his four years in the Marines and returned home to Des Moines in late 1998.

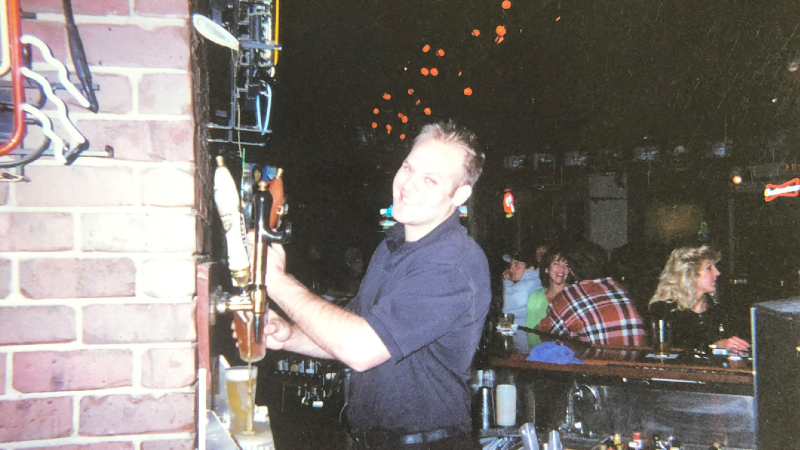

He returned to school at our local community college the following spring, then got married a year later. It was during this time Scott started to struggle with alcohol. He had been drinking since high school, but this is when we all saw the abuse begin. In hindsight, I think this might also be when he started to “self-medicate” with drinking, for reasons we still didn’t understand.

Scott was larger than life, a big personality who loved to have a good time. But he could be having fun and suddenly get pretty loud and opinionated, which sometimes got him into trouble.

One of those times was in the spring of 2001. He was out with friends and had had way too much to drink. He ended up in an altercation when leaving the bar. He was pulled out of his car and beat over the head with a Maglite by three attackers. He was beaten to the point where he was unconscious. The first responders on the scene told police that they didn’t expect him to make it. Scott spent two nights in the hospital, the first in the ICU with severe brain swelling. He clearly had a concussion from this incident, but to all of our recollections he didn’t do any sort of therapy to help with his recovery. Another example of, “if only we had known…”

Scott got divorced shortly after. Fast forward to the summer of 2004 and he was still struggling with alcohol, having also gotten at least two DUIs by this point. He was working as a bartender at a popular neighborhood bar and attending classes at Grand View College to complete his degree. Despite the setbacks he experienced with his excessive drinking, life was good, and he was having a great time.

Scott also met who would become his second wife that summer. They had a lot of fun together and dated intermittently for several years, before marrying in 2010.

His ex-wife has said, “His goal was always to make others laugh.” When they were first dating though, my brother was convicted of yet another DUI which resulted in him being sentenced to a work release facility for almost a year. It was during this time he picked up running, to pass the time. His ex-wife remembers:

“He was incredibly determined and needed something positive to pour his energy into. Given his athletic abilities, he was a natural runner. He started signing up for half marathons, marathons and eventually took on triathlons and then an Ironman. Scott’s desire to beat others and his own personal times kept him motivated throughout the years. He always needed a goal. His race accomplishments made him seem supernatural!”

She also said, “Scott’s competitive drive is the reason I also started running and eventually signed up for my first half marathon. He helped me realize I could do it. He saw a drive in me I never knew existed.”

I love that memory of Scott – of him being able to inspire his ex-wife to become something greater than she even realized she could be. One of his longtime high school friends shared a similar feeling about him:

“Scott was an encourager. Sometimes bad, but I would never have started running without him. I still hear his voice late in a workout or when things get physically hard saying, ’Don’t give up, let’s go!’ A lot of my best finish times came from fear of being chased down by Scott late in a race. Once I could get out in front of him, I did not want to hear him say something as he was passing me. And you know he would always have a smart remark!”

Scott and his ex-wife had a daughter in 2014, then divorced a little over a year later in 2015. She said, “During our time together, Scott drank too much. He hid bottles throughout our house. He said he had a hard time falling asleep, so he’d take Benadryl late at night to help. We fought about that, and the drinking, a lot. Eventually, I couldn’t live with it anymore.”

Over the next five years, they tried to be a family again a couple different times but just could never make it work. It often had to do with his alcohol addiction and major mood swings.

My brother, my beautiful, beautiful brother. He was struggling more than any of us knew. Again, if only…

During the summer of 2016, I remember my parents threw out the idea that Scott was possibly suffering from CTE, in response to some erratic behavior he was exhibiting. I completely blew it off, scoffed even, that they were simply making excuses for his bad behavior. After all, he hadn’t played football in 20 years! I wrongly assumed (did not take the time to inform myself) CTE could only happen to football players, and it showed up shortly after they were done playing. I could not have been more wrong.

From 2015-2020, Scott competed in countless races. Running was his other addiction. He loved the challenge that triathlons gave him but running was his passion. He was an incredible runner. So fast. He participated in our local IMT Des Moines Marathon every fall and was able to qualify for the Boston Marathon with a qualifying time of 3:07. He then ran Boston in 2015, finishing in 3:30. That year, the weather was especially bad. It was cold, rainy, and windy. Brutal conditions for my brother, who was an absolute lover of the heat.

Something I haven’t mentioned is that Scott was also an avid smoker. I know, an incredible athlete who treated his body like a temple when it came to exercising and the food and supplements he put into it, but yet he could drink like a fish and smoked too! One of the things that drove me crazy about him was how, after a race, he would immediately pull out a cigarette and light it up. Right in the middle of the crowd of runners who were likely not interested in inhaling his secondhand smoke. Back to his run in Boston; I was scrolling through his race pictures online, after he passed, which was a very bittersweet experience. I came across a string of three or four and couldn’t believe what I was seeing. He had stopped during the race, lit a cigarette, and then was running while smoking. Clearly, he had had it with the weather and the race! Such a funny moment, one I wished I’d known about prior to him dying, so I could razz him about it.

Scott’s biggest race accomplishment would undoubtedly be his Ironman. He did Ironman Wisconsin in September of 2018. Scott got his last DUI in April of 2017. Long story short, he ended up with an ankle device for a year, was not allowed to drink for that next year or he would go to jail. Scott poured all his energy into getting healthy and training for and then completing that Ironman.

Sadly, once the ankle device came off, he started drinking again. He thought he could handle it, control it. A game so many addicts play.

He continued to run in races, up until the world shut down in March of 2020. I think he was supposed to participate in our local St. Patrick’s Day run that March, but was unable to after its cancellation.

Scott’s drinking was getting out of control, though none of us fully understood how bad it was. So many who knew him, who loved him, have said, “if only he could have had his races, maybe they would have provided the focus he needed…”

In 2020, Scott would have done the following races, because he had done them for countless years before: Drake full or half marathon in April, DAM to DSM in June, then he would have been training for the IMT Marathon in October.

The world had shut down though and all runs had become virtual. He didn’t have his running community, the connection he desperately needed.

Another one of his longtime high school friends wrote this:

“Scott was a true friend. I thought I knew most of what was going on in his life. There were certainly a few flaws (which we all have), but things on the outside seemed to be just fine. His story is a good reminder to dig deeper to make sure your friends are okay, and to make sure they know to call if they need someone. Scott’s one of a kind, a hilarious super athlete who was always down for a great time. I think about him every day, and am really sad we could not give him what he needed in the end.”

I wish more than anything that we could go back, help Scott, save him. If only we had known then, what we know now.

When I look back, things really started to unravel for Scott the last eight weeks of his life. But in actuality, it probably started happening many months before that. Our dad’s thoughts on this:

“Scott’s patience and mood changed slowly the last year or so leading up to his death. He dramatically became more negative and there were many incidences of Scott quickly losing his temper, having seemingly unprovoked outbursts. He knew something was wrong with his thinking and ability to control his temper. We talked about it, and he decided to see what could be determined by seeking medical help. Unfortunately, he never made it to that appointment.”

The appointment our dad refers to was one at our local VA. It was an appointment to see if Scott was suffering from a TBI, or traumatic brain injury. His appointment was scheduled for October 7, 2020. He never made it because he died by suicide on September 18, 2020.

Some of my recollections during those last several weeks: My brother was upset about his ex-wife meeting someone new. He apparently thought they still had a chance at getting back together, becoming a family again. He started calling her incessantly, made a verbal threat of harm towards her new boyfriend, just a couple examples of his erratic behavior. She took legal action and had a no contact order, and then a restraining order, filed against Scott. We fully supported her. All of this, along with the fact we didn’t fully understand how depressed Scott was, how out of control his drinking had become, or how to get him the help he desperately needed, led to his first suicide attempt on September 7, 2020.

As I sat with him in the hospital that night, he told me he was tired of being a burden. It broke my heart. He was absolutely not a burden to anyone. Was he scaring all of us? Yes, absolutely. His behavior was out of control. He was out of control. He also told me something was wrong with his head and he was going to have a TBI study done soon. At the time, I had never heard of a TBI. When he explained to me what it meant, I told him he just needed to stop drinking and get on the right antidepressant. He had a brain injury, was literally losing his mind, but I simplified it as, “just stop drinking and get on the right meds…” If I’d only had the information then that I have now.

My brother was released from the hospital the next morning and then arrested the same afternoon for breaking the no contact order. When he attempted that first suicide, he had done it on his ex-wife’s front steps. How much that scared her, I will never know. I am certain Scott’s intention wasn’t to scare or hurt anyone. Yet, that’s exactly what he was doing, scaring all of us.

He spent four nights in jail. Our dad bailed him out on Saturday morning. He came over to my house and had dinner with us. There were lots of tears and honest conversations, lots of hugs too. He felt so bad about what he had done, how he might not get to see his little girl for a long time due to his actions. He seemed to be in the right head space though, seemed to “get it” and wanted to take the steps to be better, and get better.

As the week went on, he started to get more and more agitated. We were texting a lot throughout the day each day. He came over for dinner again on Wednesday night. Looking back, he had been drinking. He wasn’t supposed to be drinking and I didn’t think (at the time) he was. As he was leaving we stood outside and talked for probably 30 minutes. The conversation was one I had a hard time following. Scott was so upset again, angry, and not making a lot of sense. At one point he was tapping the back of his head, saying, “I know there’s something wrong with my brain!” I was trying to talk him down, but he left mad. I wish so much I could go back to that night and just hug him, hold him, and tell him I love him, that it would all be OK.

I talked to our dad the following evening, explaining how I didn’t think Scott was doing very well, and seemed really agitated again. We agreed we needed to take steps to help him. The next morning our dad called and spoke to Scott’s therapist about our concerns. Scott then had a virtual appointment with her, where she shared our worries with him. He texted me after saying he shouldn’t have shared so much. I said no, he should definitely share, just not threaten harm. I explained we were all so worried because of how erratic his behavior had been lately, and if he hurt the boyfriend, he would effectively end his life as he knew it, meaning he would go back to jail. His response was, “Don’t worry, I won’t hurt him.” I will forever regret not responding with, “Don’t hurt yourself either,” but I didn’t. We texted a bit more, about how he was going to come over in the morning to go on a 50-mile bike ride with my husband. My husband was training for his first half Ironman and Scott was going to ride with him. A ride that never happened.

Approximately three hours after our last text, my brother would die by suicide. He had driven by his ex-wife’s house, breaking the restraining order. The police came to arrest him again. My dad called Scott, explained they were on their way and told him to comply. Scott pulled a pellet gun on the officers. It wasn’t a gun that could do real harm, but it looked like a real gun. Scott purchased it during quarantine for target practice to get him out of the house. Having been a Marine, he had a lot of respect for authority and would never hurt a police officer. They had no choice but to shoot him though. It’s what my brother was counting on, for them to end his suffering.

The morning after Scott died, our dad called the medical examiner, asking him to please have Scott’s brain tested for CTE. Due to the manner of his death, we were only able to send the UNITE Brain Bank small samples of tissue from Scott’s brain. It often takes close to a year to get the test results back. We got the results back on October 11, 2021. It was confirmed, tau protein was found, which is consistent with early-stage CTE, but the researchers needed the whole brain to get an official diagnosis. Still, the study provided so much validation because Scott knew something was wrong with his brain.

I am sharing Scott’s story, so many details of his story, because I hope (we hope) it will help someone. If someone can read this, recognize these symptoms in their loved one, and help them, then his death won’t be in vain. I urge all parents to consider programs like Flag Football Under 14 to prevent unnecessary repetitive head impacts when children are too young. I don’t want another family to have to live with the “what if” and “if only” we live with. If only I had known what CTE really was, if only I had seen CLF’s website and social media page sooner, where you can read about the signs and symptoms of CTE.

On October 28, about six weeks after Scott died, I came across a post a friend had made on Instagram. It was a post about a charity event for CLF, the Concussion Legacy Foundation. I clicked the link and started reading, then started crying. I saw the post which listed the signs and symptoms of CTE. It was all there, and it was all so clear: THIS is what my brother had been suffering from. And there was a Helpline. A Helpline?! What if I had seen that Helpline?

What if I had seen it six weeks before Scott died, instead of six weeks after? What if? If only..

To my beautiful, beautiful brother: You were loved. Loved SO much. You were worthy. Worthy of a GOOD life, free of the pain you were suffering from. And you were never, EVER, a burden.

Suicide is preventable and help is available. If you are concerned that someone in your life may be suicidal, the five #BeThe1To steps are simple actions anyone can take to help someone in crisis. If you are struggling to cope and would like some emotional support, call the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988 to connect with a trained counselor. It’s free, confidential, and available to everyone in the United States. You do not have to be suicidal to call.

Are you or someone you know struggling with lingering concussion symptoms? We support patients and families through the CLF HelpLine, providing personalized help to those struggling with the outcomes of brain injury. Submit your request today and a dedicated member of the Concussion Legacy Foundation team will be happy to assist you.

Tevin Hendrix

Donnovan Hill

Zach Holm

Warning: This story contains mention of suicide and may be triggering to some readers.

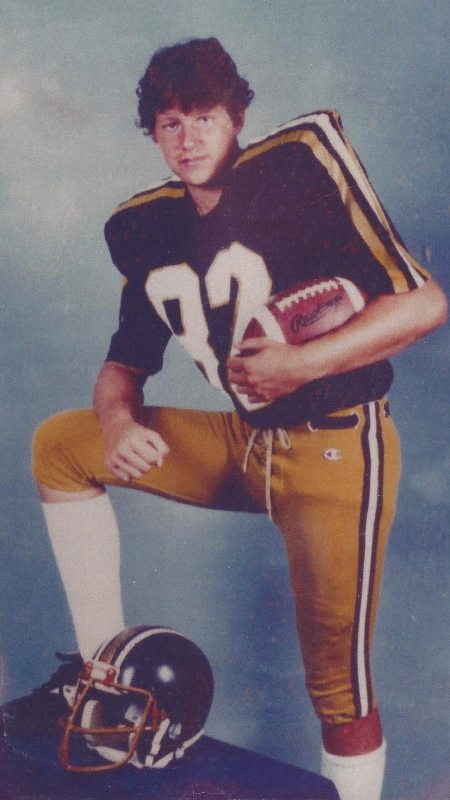

Special. This is the word most often used to describe Zachary Ryan Holm. The first time we heard it was when he started played flag football at age six. Growing up in Florida, Zach was very blessed to have been coached by former NFL and college football players. From an early age, Zach was encouraged to work hard and was told he would be able to go as far in football as he desired. Zach took this to heart. He was a big kid, so he began playing competitive youth tackle football at age seven, playing every position on the team. At age 10, his coach called him “hybrid” because he was big, strong, fast, and smart. He started playing quarterback and continued all through high school. Going to a small high school in Colorado, Zach ended up playing both sides of the ball and led his team in touchdowns as well as tackles. Zach was recruited to play safety at the University of Wyoming. At six-foot, he was considered “short” for a quarterback but UW coaches were impressed with the hard hits Zach delivered on defense, so they recruited him to play safety.

Those hard hits over many years Zach delivered on defense, and the hits he took as a QB set him up for CTE. Zach had five known concussions, the first of which came at age nine. He started having problems with depression at age 13 and had difficulty sleeping and with concentration at age 16. Zach started attention deficit disorder (ADD) medication at age 18. The medication initially helped with depression and concentration, but the therapeutic effect started to wane. Zach was excited to be recruited to play football at a D1 school, but his depression worsened. He told me, “Mom, the football wasn’t hard, it was the depression that was difficult.” Zach resigned from the UW team during his freshman season in December 2016 and never returned to football. Zach’s first paper at UW was about CTE. He highly suspected he had CTE from playing 12 years of tackle football.

After UW, Zach transferred to a private college in Florida and really struggled with depression. He returned to Colorado to be near family. Zach battled suicidal thoughts and was open about his suicidality. Zach felt guilty about being depressed because he felt like he had everything going for him. He started feeling “numb” and said, “my brain is broken.” Zach participated in any form of therapy offered. He tried multiple medications and even ketamine infusions which helped for about 24 hours. He was compliant with every therapy and was disappointed when none of them helped. We talked about CTE. Zach knew it was a diagnosis only made at autopsy.

Zach attended a private Christian school in Tampa from ages four to 13. This is where his Christian faith was solidified. He was a leader both in the classroom and in every sport he played. Zach was called very “special” by his teachers and classmates. His kindergarten teacher described him as “a mix of sweetness and testosterone.”

Zach loved tattoos and had scriptures tattooed on his arms. In 2016, he decided to get a chest piece tattoo depicting a demon fighting an angel over his heart. Zach said he always wanted to be reminded he was not alone in his fight against depression and the devil.

Zach’s depression was growing worse, and he was getting daily headaches and hearing high pitched noises, causing physical pain. An MRI of his brain was normal. Medications were not helping with his mood. He was evaluated by five psychiatric professionals, the last of whom informed Zach he had treatment resistant depression. He tried nonprescription drugs which helped a little. Despite all these mental health challenges, Zach was attending the University of Colorado and getting excellent grades. Then he got COVID-19 in November 2020 and had to take a medical withdrawal. Zach was set to begin classes again in June 2021 with the eventual goal to attend law school. He was extremely driven as can be seen in the following excerpt from his LinkedIn page:

“Most people who know me describe me as a chronic perfectionist, as I give everything that I do my full attention and effort. In conjunction with time management, perfectionism is very beneficial. From my perspective, there is no point in me doing something if I do not intend to do it to the fullest of my capability. I am driven to be the best at whatever it is that I decide to do.

What differentiates me from the rest of the pack is my passion and drive for success, which is reflective with my persistence and consistency in terms of my work ethic; once I set my mind to something, nothing will be able to stop me from achieving it.

This is reflective of one of my firm views, which is the significant dislike of complacency. There is nothing more detrimental to the individual than complacency.”

Zach met a special young lady in the middle of his physical and emotional turmoil, and they were blessed to bring a beautiful baby girl into this world in 2020. Zach was an excellent father. His baby was the light of his life and became his purpose for living.

Zach became ill with acute respiratory symptoms in March 2021, and he took over the counter cold medicine which negatively interacted with his depression medications. He died from serotonin syndrome on March 27, 2021. We were able to donate Zach’s brain to Boston University for their CTE research. An hour after we heard of his death, we were contacted by Donor Alliance because he had signed up to be an organ donor. They described Zach as “special” because he was young and muscular and would be able to help about 50 recipients with the donation of his corneas, skin, bone, and muscle.

At Zach’s memorial and for months afterwards, we were contacted by people who had been touched by Zach’s life. Stories of him feeding the homeless, stopping someone from jumping off a bridge, and being a “special” person because of his incredible faith and love for his family. Zach always looked out for people who struggled. We often had stray kids staying at our house when they had difficulties at home. Zach was described as “kind,” and received the fruit of the spirit award at Christian school for “gentleness.” All of these attributes were far more important to him and to us than his stats on the football field.

Ten months after Zach’s death, we had a meeting with Dr. McKee from Boston University. She verified Zach had stage 2 (of 4) CTE. Zach had multiple lesions in various areas of the brain responsible for mood and impulsivity. Dr. McKee described Zach’s severe brain damage as unexpected in a 23-year-old. Also, it was no surprise to Dr. McKee hearing none of Zach’s medications really helped with his depression and anxiety.

This news from BU was devastating but also comforting, because Zach knew his brain was “broken” and he worked hard to stay ahead of his depression and suicidality. After meeting with Dr. McKee, I had my first dream about Zach after 10 months. In it, Zach was whole and happy. He also had a bounce to his step, and I am sure he was telling me, “I was right about my brain.” Zach always liked to be right!

We are blessed to know our very special son is still helping others. Zach’s experience and study participation are helping researchers to make changes in football so it is safer, and his death is helping to develop more useful ways to diagnose and potentially treat CTE. We are crushed about losing our son. At the same time, we are proud of his insight into brain injuries and his prediction regarding his CTE. Zach’s knowledge fueled our desire to donate his brain to Boston University. As everything else Zach did on this earth, his participation in the BU study was “all in.”

Mike Jenkins

Mike dedicated his life to coaching, mentoring of teams and players, helping keep field maintained and safe. That was the dad in him, but there was so much more. He was always the person that if someone was in need of help or a sounding board, he was there. In his life he was placed in the position of administering CPR to someone in need. He would have given all he had to someone less fortunate.

My name is Marcia Jenkins and I am Charles Michael “Mike” Jenkins’ Mother. I remember so clearly the day I answered the phone and the voice on the other end said “ just calling to let you know Mike will be playing pee wee football for the YMCA Packers.” He was seven years old. It only took a few practices to know he was born to play football and anything else that used a ball. “He was talented,” they said. He would start at quarterback. Over the years the teams he played with always were champs. Such a joy of his dad, Jack and me.

As he grew in size, strength and talent, so did the intensity of the games. By the time he reached junior high he traded Quarterback for tight end. He loved to run down the side line and leap for that touchdown pass. He was the starting tight end for Warren Central High School in Indianapolis from 1981 to 1983. Oh, how we all cheered. We were all so proud, including his girlfriend Kim and later in life his wife of 23 years. There was no way of knowing we were watching him travel down a path not to glory days of football, but the path that would someday lead him to glory…by the way of hell.

Mike put himself into everything he did, catching passes, throwing pitches, dunking basketballs, or racing motor bikes with his brother Rick. His wild and full-out life style got him the nick name “Crash.” Crashes in football fields, second base, doors, swimming pools and much more. Each one laying the foundation for concussions … if we had only known.

After graduating from Warren Central, he attended University of Indianapolis. In July of 1987, he married the love of his life, Kimberly Sue Basey. In the early days they enjoyed playing with friends on softball teams, waiting for the time there would be a new generation of players to come. In 1991 their first son, Kyle Michael, was born. The dream of every man: a “SON.” The tears rolled down his face. In 1994 their second son, Nicholas Michael, was born. He told me, “Mom I know why I am here. I am giving everything I have to these guys.” When Kyle turned five-years-old the merry-go-round of season to season, sport to sport started.

Mike dedicated his life to coaching, mentoring of teams and players, helping keep field maintained and safe. That was the dad in him, but there was so much more. He was always the person that if someone was in need of help or a sounding board, he was there. In his life he was placed in the position of administering CPR to someone in need. He would have given all he had to someone less fortunate. On the day he died, he was playing ball with Jas, the boy next door, and mowed that same neighbors grass. Jas’ dad, Jim, was dying of cancer at age 45.

Now that I painted this beautiful suburban picture of the “happy ever after” family, things begin to change some subtle, others so obvious.

Kim Jenkins, wife of Mike Jenkins

I am Kim Jenkins and Mike was my husband, best friend and father to our two boys, Kyle and Nick. We met back when we were in elementary school and I believe it was love at first sight. We dated off and on, but started dating for the final time in August of 1982 and got married July 25, 1987. We were married 23 years prior to his death. Mike loved me and the boys more than anything and would do anything for us. There would be times though that Mike would have anger outbursts and would say things to me that I know was not him talking, and later he would tell me that he hated himself and wanted me to hate him too; that he didn’t feel good enough for me and that I deserved better than him.

Mike struggled with alcoholism and did everything he could to beat it, but just wasn’t able to and that was the main reason why he hated himself. Mike would ask me what was wrong with him that he couldn’t beat it. I just wish we had known then what was going on in his brain that was causing it because maybe then he would not have hated himself and could have handled it or found ways to deal with it.

I am so glad Mike got to meet our granddaughter before he died. Jayda was born on March 23, 2011, so she was only a month and a half when he passed away. He would lay on the couch with her on his chest while she slept. He loved her dearly. I know she sees him at times. She has told me that he is funny and makes her laugh. She has some of his characteristics, so I know he also lives on in her and it makes me feel like he is still here with us through her.

Mike was the type of person that would give anyone the shirt off his back to help them though. Mike would try to help our friends out when they would have problems. Mike would talk to them to help them any way he could. Our neighbor, Jim, who was the same age as Mike was diagnosed with cancer and Mike took over doing their yard work and helping with his young boys. The day Mike died he had gotten their youngest son off the school bus and was watching cartoons with him when I left the house. He had been out with their other son doing yard work and spending time with him.

Mike had had multiple concussions over the years but his last one in February 2011 when he fell on the ice was totally different. After that concussion Mike got sick about every other week with post-concussion symptoms and couldn’t figure out what was wrong that made him so sick. Mike missed lots of Nick’s high school baseball games that year and he was the type of father that never missed a game no matter how he felt. Mike was like a different person after that fall. There were times that I could be talking to him and it would be like he wasn’t even there, he would have a blank look in his eyes. There was one weekend that he didn’t even get out of bed. After his death we found out that he ran into a friend that he had known since childhood and didn’t even know him at first. Upon talking to coworkers of Mike’s we also found out that he was acting different at work, too. He was being combative with co-workers and he was not like that before. One of his friends that was also a coworker was riding with him on his route and he spaced out at the wheel of his semi and the friend had to grab the steering wheel to keep them from crossing the center line.

The day Mike took his life I will never forget it. I was so totally shocked because I never expected it. I had talked to him just a few hours prior to that and he was talking about Mother’s Day, which was coming up that weekend. He had told Kyle he was going to fix them dinner on the grill and even had the meat thawing to cook as Nick and I were at the high school working in the concession stand for baseball. Mike had even called me up there and asked if we needed any help in the concession stand.

Nick, son of Mike Jenkins

My name is Nick Jenkins and I am the son of Mike Jenkins. My dad was always my biggest role model growing up. He always worked so hard and would do so much to give me and my brother everything we wanted growing up. I learned so much from my dad while I was growing up. From having a good work ethic, to playing sports, and most importantly how to properly treat people around me. I was always close with my dad throughout the years, but the thing that brought us closest together was playing sports. Pretty much everything I learned in basketball, baseball, and football was from my dad. I can remember back to my first year playing football. I was the quarterback for my little league team just like my dad. I remember spending countless hours in the driveway going through all of the plays and working on my footwork so I would be prepared for the games. We also spent countless hours playing basketball one-on-one in the driveway. I can still hear him giving me pointers on my shot when I play basketball today. Out of all the sports I played, the sport he worked with me the most on was baseball. Baseball was always my best sport growing up and my dad was always there to practice with me whenever I wanted to go out in the yard and work to make myself better. He would throw me batting practice, catch for me when I wanted to pitch, and hit me ground balls and pop flies. The thing I loved most about my dad was no matter how he was feeling or what was going on he would almost always be at my games. Up until he had his last concussion I could count on one hand how many of my games he missed prior to that. There is one game that comes to mind that he missed. I was 13 at the time and I was pitching that game. It was probably the worst game I had ever played. My coach ended up taking me out after 20 pitches because I couldn’t throw a strike. The next day when we had another game my dad was there and my coach started me pitching again. I ended up throwing a complete game shutout and got the game-winning hit. Just the presence of my dad being there made me perform so much better. It was definitely tough on me losing my dad, but the way I look at it now is he is always with me and looking over me.

Kyle, son of Mike Jenkins

My name is Kyle and Mike was my dad. My dad helped mold me into the man I have become today. When I talk about him I feel like I am almost talking about myself. I wish I had realized that we were so much alike before he passed. He was a truly selfless person whether he knew you or not. My dad got his greatest joy out of helping others, because that is what he was sent to do. One time he gave CPR to a man at a NASCAR race who’d had a heart attack and it saved his life. Dad was a straight forward man and would give you a straightforward answer to any question. The only thing he ever lied about was his own problems, because his biggest fear was disappointing his family. What some people didn’t know, and I don’t think he even knew, was that the problems he had made him the man that he was. My dad had a high expectation of himself and failure at anything was hard on him. Whether he was at work, working around the house, or being a father he did everything to the best of his ability. He was a great family man and was always there for me and my brother when we needed him. I miss him every day, but I am proud of my father for who he was and who he helped make me become.

“Only in Death Shall I Achieve Peace”

Rick, brother of Mike Jenkins

My name is Rick and Mike was my brother. Mike and I were not the kind of brother’s that talked all the time or spent a lot of time together. We were the kind of brothers that were always there for each other, no matter what. On Easter Sunday 2011 after having dinner together, Mike couldn’t remember how to get back to my home, I live in the neighborhood we grew up in. I believe it was at that time that I realized we were in real trouble. It was the last time I saw him. He died a few days later.

I had heard about CTE prior to that but never thought it would hit so close to home. I really don’t know what I would have done had it not been for Boston University and their results. It really brought comfort to know that it was not my Mike that did that to himself that day; that it was something else going on in his brain. Since his death I have learned so much about CTE and the things I have learned have made me realize that Mike had been suffering with symptoms of it for years and we never knew it. I just hope that someday they will be able to find a way to diagnose it in someone and be able to come up with some kind of cure or at least help for anyone who is diagnosed with it.

I miss Mike so much, but I know he is watching over us. He comes to us at important times as a Cardinal and I cherish it more than anything.

Suicide is preventable and help is available. If you are concerned that someone in your life may be suicidal, the five #BeThe1To steps are simple actions anyone can take to help someone in crisis. If you are struggling to cope and would like emotional support, call the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988 to connect with a trained counselor. It’s free, confidential, and available to everyone in the United States. You do not have to be suicidal to call.

If you or someone you know is struggling with concussion or suspected CTE symptoms, reach out to us through the CLF HelpLine. We support patients and families by providing personalized help to those struggling with the outcomes of brain injury. Submit your request today and a dedicated member of the Concussion Legacy Foundation team will be happy to assist you.

Claude Johnson

Claude Alton Johnson, proud son of Boone, N.C. and pride of Morristown, N.J., beloved husband of Tina, proud father of Christopher and Kathryn, died on July 5, 2022, after a long wrestling match with dementia. Unlike his matches as a cadet, this was one he could not win.

Claude was the son of Ola and Hal Johnson and grew up with his four siblings in the Appalachian Mountains. He was a fierce wrestler in high school, becoming state champion before joining the Army as a cadet. As a four-year letterman on the team, he wryly said he, “won more matches than he lost!”

Claude was one of the kindest, most warmhearted, adventurous, fun-loving, and caring people we knew. He loved life, and the ladies universally loved his soft, inquisitive Southern drawl, which he used to the fullest. A classmate once told Claude he thought it was great their Southern accents allowed them to bamboozle people.

During his freshman year, Claude met the love of his life, Tina. They were married at Holy Trinity Chapel at West Point in November 1968. Claude proudly served in the Army for five years as an Air Defense Artillery and Adjutant General Corps officer, and he received the Bronze Star Medal for his service in Vietnam. He spent a year in the Replacement Battalion at Long Binh. As the Liaison Officer to a refugee village outside Saigon, Claude was able to see many classmates and friends who came into the country or were going home during that year. On weekends, he would take “volunteers” (all the beer you could drink!) to work there. During their tenure, they built a school and endeared themselves to the residents. For his work, locals even gave Claude a gold medallion inscribed “Our Benefactor” and presented him with a proclamation calling him “Man of Our Hope.” The most difficult part of the assignment was the day he left Tina and his newborn son Christopher, who was only three days old at the time.

Claude’s subsequent corporate and entrepreneurial careers in data management and operations research afforded him even more exposure to the world. With his immense thirst for new experiences, travel was a real tonic. He lived by the ethic that a stranger was simply a friend he had not yet met. Millionaire or homeless, it never mattered; all received the same treatment. Claude just loved people. He was a selfless, honorable man who left a mark on everyone he met.

Claude had a special gift. His quick wit was wrapped in an enigmatic and wry sarcasm, often befuddling listeners as to whether Claude’s expression was simply inane or brilliantly astute. He loved the role, and it endeared him to everyone. In business as well as in the Army, he diffused situations with humor and charm.

Adapting to any situation was Claude’s specialty. Whether in a new position or in a new location, he was on it instantly. Through military and civilian assignments, he moved 15 times. It was always an enriching experience for him. His only mistake was presuming he had to own a house wherever he moved, even with several relocations within a year! Claude often said it was like witness protection but being allowed to keep your own name. His real estate advice was jokingly, “Buy high. Sell low!”

Claude had intense pride and love for his family: Tina, his wife of nearly 54 years; son Chris (Jenn) Johnson, and daughter Kathryn (Bill) Gates as well as three adored grandchildren, Hunter and Payton Johnson and Emily Gates. Besides being with the grandkids, volunteering and gardening were Claude’s true joys.

His volunteer efforts ranged from coaching high school wrestlers to working in soup kitchens. After retiring and living in Florida, he spent several hours a week at a local nursery. Other days, he and Tina worked in a school program assisting needy districts. Upon returning to Morristown, N.J., he volunteered at the Frelinghuysen Arboretum, where he was recognized as Volunteer of the Year. They also spent many happy hours at nourish. NJ, a community soup kitchen. Truly a Renaissance man, he would de-stress by creating masterful works of art in needlepoint!

As a result of his athletic endeavors, Claude selflessly and generously elected to donate his brain to the UNITE Brain Bank, where researchers diagnosed him with stage 3 (of 4) CTE. We hope his contribution will aid in the development of a blood test to isolate CTE and other dementia contributors, as well as effective drugs to combat them.

We will forever encounter Claude in our memories and our hearts. We will find him as he always was: clever, kind, caring, gently mischievous, and fiercely devoted to family and friends forever. He was easy to love…and still is.

Tom Johnson

On the morning of February 8, 2015, I received the call from Tom’s wife. She told me Tom was gone. At first, I thought she meant he had left. I guess in a way he did. He left in the middle of the night and escaped the demons that haunted him during the latter years of his life.

Tom was the youngest of my three boys. He grew up in Brockton, Massachusetts, which is known as the “City of Champions” because boxing legends Rocky Marciano and Marvin Hagler grew up there. Tom’s father left our family without notice when Tom was only three years old. Despite growing up in a single parent home, there was no shortage of love from myself and his two protective older brothers, John and Dave. Tom and his brothers were gifted athletes at an early age and played baseball, football, basketball and several other sports. As a single mom working multiple jobs, I was thankful for athletics to keep them busy and largely out of mischief. I could never have envisioned Tom’s gift for all sports, particularly football, would contribute to such a marked demise in his quality of life and a premature death. It’s a parent’s worst nightmare, and I will always struggle with this guilt.

In addition to being a gifted athlete, Tom was an outstanding high school student, a member of the National Honor Society, and a very well-liked person. The combination of his athletic and scholastic talents made him stand out to his friends, teachers, teammates, and to his renowned high school football coach, Armond Colombo. Tom had strong beliefs about right and wrong, and he developed many lifelong friendships growing up in Brockton. Tom was an unconditional friend and his friends’ battles were Tom’s as well. His confidence and lack of pretense enabled him to converse with a homeless person just as easily as he could with President George H. W. Bush, who he met while attending the President’s Cup golf tournament.

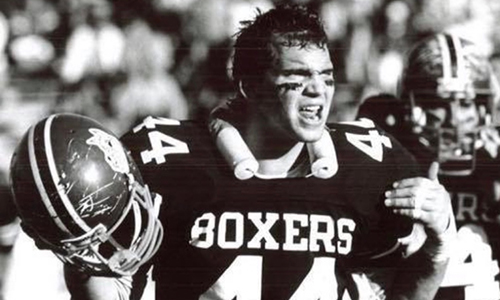

Tom played on the varsity football team as a freshman and was a star player each of his four years. This was a significant achievement considering the rich football history at Brockton High. The team went on to win three Massachusetts High School Super Bowl’s during the four years he played, losing only one time in his four seasons. Tom was co-captain and team MVP his senior year and named to the Enterprise All-Scholastic honors and selected to the Shriners All-Star team. Posthumously, Tom was inducted into the Brockton High School Hall of Fame in 2015.

Tom occasionally played fullback, but his primary position was middle linebacker. Tom loved battles, and at this position, he could outsmart, anticipate and use his speed and strength to tackle opposing ballcarriers. “It’s a gridiron war,” he and his teammates would often say. His teammates gave Tom the nickname “Captain Crunch” because he played with such reckless abandon to ensure his helmet connected with the ball carrier. Back then, Brockton players often compared helmets to measure who had collected the most dents and scratches throughout the season. The more damaged the helmet, the better. Tom’s helmet was frequently the most damaged.

During his high school football career, Tom suffered many “bell-ringers,” as they were called then. These were frequent, and not taken seriously by Tom, his teammates, or any of us. During one game against a team from New York, Tom suffered an especially serious concussion and was taken by ambulance to the hospital. Despite being diagnosed with a concussion on Saturday, he was back at football practice on Monday. During Tom’s high school years, 1985-1988, concussions weren’t newsworthy or ever a deterrent to sports.

Tom was offered several scholarships from various colleges and universities. He decided to attend Colgate University in Hamilton, New York. He played less in college than in high school, primarily due to a poor relationship with his coaching staff. In a game against Army his junior season, he suffered another serious concussion. He was not examined and diagnosed until several days after the impact and was sidelined for the next game. Soon after, people close to him noticed escalations in certain behaviors and we became concerned with his mental health.

Tom was always excitable and prone to fights, but after that concussion he became more erratic and he frequently escalated minor conflicts. He began drinking more often and acting out in ways that occasionally resulted in property damage and fights. At one point during his senior year, he was asked to take a leave of absence from school after an unprovoked altercation. Previous attempts by a girlfriend to get him to engage in therapy at school counseling sessions were short-lived. When Tom came home to be with his family for that year off from college, he told us about a traumatic incident that occurred during his childhood. After that admission, he willingly participated in therapy sessions and seemed to be on a great track as he returned to Colgate to complete his senior year and graduate in 1993.

After college, Tom moved to New York City and became an assistant specialist on the American Stock Exchange with the prominent firm Spear, Leads & Kellogg. He was considered such a prodigy at auction market trading that he was assigned to support one of the ASE’s busiest and most high-volume stocks: Motorola. After several years in New York, he realized how much he missed his family and friends and decided to move back to Massachusetts where he found work with Citigroup in their analyst program.

It was after a trip to Ground Zero to volunteer after the events of September 11, 2001 that Tom surprised everyone with his decision to enlist in the Marines. No one could have stopped him; he was incredibly determined to serve his country. In 2002, Tom departed for boot camp at Parris Island, NC before being deployed to Iraq. He served honorably on special operation tours and was awarded several commendations, including a Global War on Terrorism Service Medal, the National Defense Service Medal, and a Medal of Good Conduct.

Tom was discharged in 2006. Despite his commendations and awards, Tom was severely affected when he came back home. His behavior was erratic and irrational, his drinking was excessive, and his tendency to resort to violence escalated. He no longer resembled the incredibly loving son, brother, uncle, and friend we all knew. We were all concerned for him.

His condition grew worse with each passing year. In 2007, Tom attempted to take his own life. He was taken to a local hospital and then transferred to the Brockton VA Hospital for observation and treatment. He remained there for two weeks. He worked hard to convince his treating psychologist that he would be OK with outpatient therapy and he agreed to go to AA meetings. He seemed to be getting the help he needed and returned to spending time with friends and family. For these reasons, we saw the attempt to end his life as an aberration and not something we would ever revisit again.

Soon after, Tom received a job offer to work at the Naval Academy Prep School (NAPS) in Newport, RI. For a few years at NAPS, he was at his happiest professionally and seemed to be on the most positive trajectory. He worked as a system engineer and volunteered as an assistant football coach, mentoring kids who he truly loved. He also obtained a Master’s in Science Communication from Stayers University in Virginia. All seemed to be going great for Tom and I had never seen him happier.

The changes began to creep into our lives so slowly it’s difficult to pinpoint exactly when they began. Perhaps the first blow can be tied to when the chain of command at NAPS changed and Tom was informed his position and coaching role would be eliminated, along with his assistants. He was living away from home, so I did not see him enough to notice any day-to-day issues. Following an altercation at his brother’s home, he admitted himself to a drug and alcohol rehabilitation facility on Cape Cod. He maintained a position with NAPS, but they were now aware of his struggles and were initially very supportive to his illness.

Next, Tom bought a home in Middleboro and invited his fiancée and her son to live with him. They married shortly afterwards. Over the next two years he and his wife participated in AA programs, but would continuously relapse, rehab, and relapse again. He lost his job and his home life was volatile and unstable. For a while, Tom was very open to receiving help. Around this time though, he became more rigid in what treatments he would participate in. He did try a long-term rehab program at the VA where he was diagnosed with PTSD. Doctors also considered a bipolar diagnosis and he was given medication. At that time, no one knew the true cause of his suffering.

A physical altercation then led to jailtime for Tom. After he was released, he seemed to lose all enthusiasm for life and his fighting spirit. An athlete who loved engaging in physical activities no longer cared about exercise or maintaining a healthy lifestyle, allowing his overall health to deteriorate. Most notably, he cut off communication with lifelong friends and family, essentially anyone who was trying to help him help himself. His lifetime of sociability and gregariousness contrasted with his devolution into reclusive behavior. His close relationships with his two older brothers whom he idolized became contentious, fraught with tense accusations, and even violent.

In December 2014, Tom called me crying to say he believed he was dying. We had the Middleboro police go to his home and escort him to the Bedford VA hospital. Tom called me after arriving to thank me for saving him, but he asked that I not visit since he had a lot of thinking to do. Sometimes that conversation haunts me. I questioned whether I should have overruled his request and gone to visit him. I was entirely unaware that he left the hospital and the program he was enrolled in until I received the call that he had died. Though I told him countless times during his difficult years, I never got the chance to tell him then how proud I was to be his Mom. I never got to remind him how I still loved him to the moon and back and always would.

During the final years of Tom’s life, he did his very best to tackle the mental pain and anguish he suffered like he had when he was a football player. He would often complain of excruciating headaches and say how he couldn’t rein in painful, rambling thoughts. We attributed the symptoms to Tom’s tendency to overthink or to his alcohol abuse. Even when he didn’t appear to be trying, Tom was fighting an internal battle with his entire being, a battle within that was unwinnable – mentally and physically. There were times when we thought he was getting better, but it wouldn’t last. None of the numerous hospitalizations or stays in rehab facilities to recover his life could bring Tom back to a place of calm or equilibrium. His life became what he described as an unrecognizable, living hell.

A few times when I went to his side and held him, he would ask me to please pray with him and his prayer was always the same, “Mom, please ask God to bring me home. I don’t want to live like this anymore.”

At the time Tom passed away, our family knew very little about CTE until his brother-in-law, Kevin Haley, notified us about the Concussion Legacy Foundation. He suggested we donate Tom’s brain to be studied for Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy, or CTE. We decided to donate his brain, and about a year later, researchers at the UNITE Brain Bank diagnosed Tom with CTE.

I will always be extremely grateful to Kevin for providing this information and helping us complete the brain donation process. Learning about CTE has changed our lives and aided us in our grieving process. Gaining an understanding of what was happening within my son’s brain helped us understand those years where we could not comprehend his changes. We just wish we had known sooner, before it was too late to make a difference for Tom. The most important thing now is to continue the work and to expand the awareness for other families experiencing what we did and provide them with hope, and measures they can take for someone they love.

I want to extend my heartfelt thanks to Lisa McHale and Dr. Ann McKee and the entire research team for their painstaking diagnosis and patient explanation of the pathological findings. For me, my family and everyone else who loved Tom, the CTE diagnosis helped explain the devastating effects on Tom’s life and greatly assisted us in healing from his death.

Tom is missed every single day, but no longer are our memories fixated on the events of those traumatic final years because we’ve been blessed with an ability to understand what caused them. We now remember Tom as he was before he began to experience the symptoms of CTE. The son, brother, uncle, friend, and person he was is the memory that will forever live in our hearts.

If you or someone you know is struggling with probable CTE, or lingering concussion symptoms, ask for help through the CLF HelpLine. We support patients and families by providing personalized help to those struggling with the effects of brain injury. Submit your request today and a dedicated member of the Concussion Legacy Foundation team will be happy to assist you.