Posted: January 21, 2020

“Before the headaches and concussions, he was very much an extrovert, he always had a group of people around him and just loved life and had a lot of fun.”

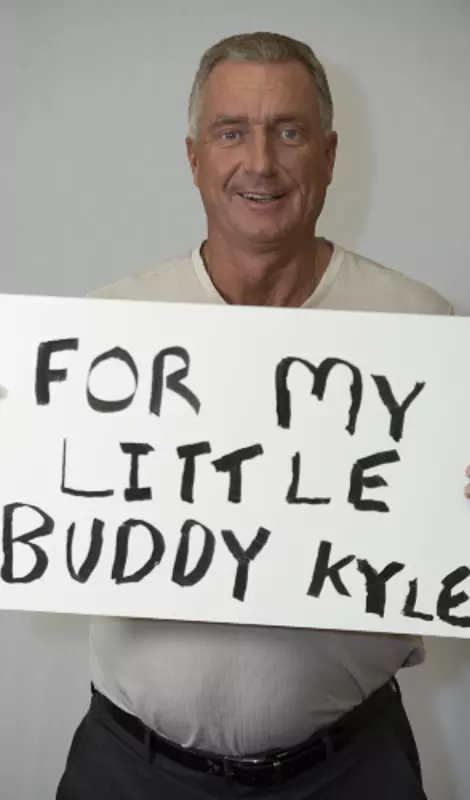

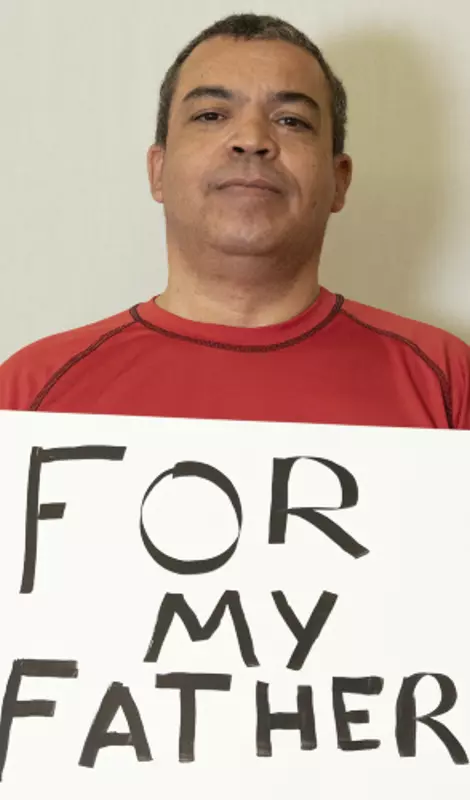

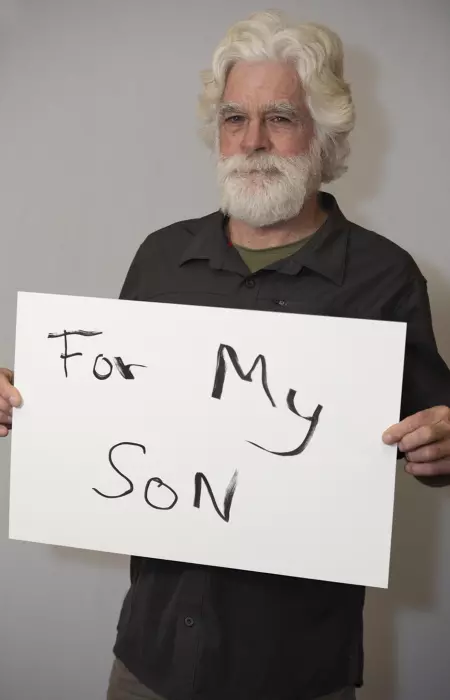

Mike Raarup says concussions changed his son Kyle’s personality. He became impulsive, and struggled with drastic, volatile mood swings. Kyle was a gifted hockey, football and baseball player in Minnesota. Concussions forced him to quit sports in 8th grade – and he was later diagnosed with Post-Concussion Syndrome (PCS). Treatments helped Kyle graduate high school and attend college, but he still suffered from anxiety, depression and memory loss. He took his own life at age 20 in November 2015.

Kyle’s brain was later studied at the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank, where researchers diagnosed with him Stage 1 (of 4) CTE. Mike is proud to have donated his son’s brain to research and supports our cause in his honor. It’s his “Why CLF”.

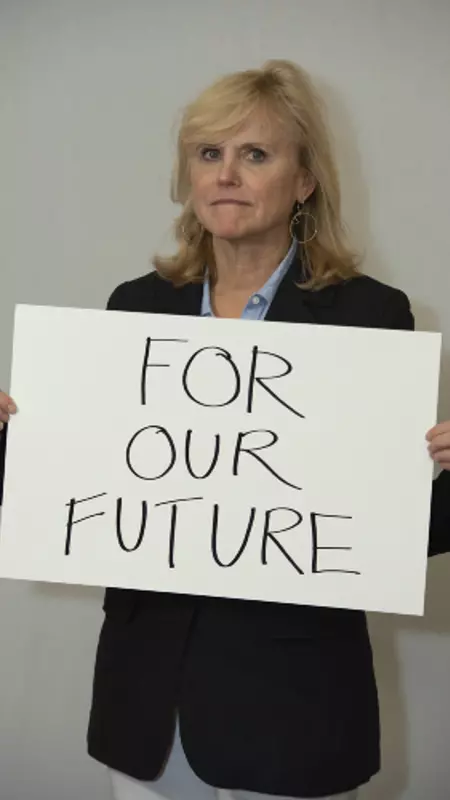

Dr. Ann McKee is leading the global effort to find a cure for CTE with her groundbreaking research. When we asked her why she persists in this work, her answer was simple.

Dr. McKee is the Chief of Neuropathology at the VA Boston Healthcare System and Director of the Boston University CTE Center and the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank. In 2018, she was named one of TIME Magazine’s 100 most influential people. Dr. McKee’s work has revolutionized the world’s understanding of CTE and changed the way we think about head trauma in sports and the military. Our future is brighter because of her work.

“He taught all of us life lessons, differently, yet all the same principles. He was our coach in many ways and was very much our hero.”

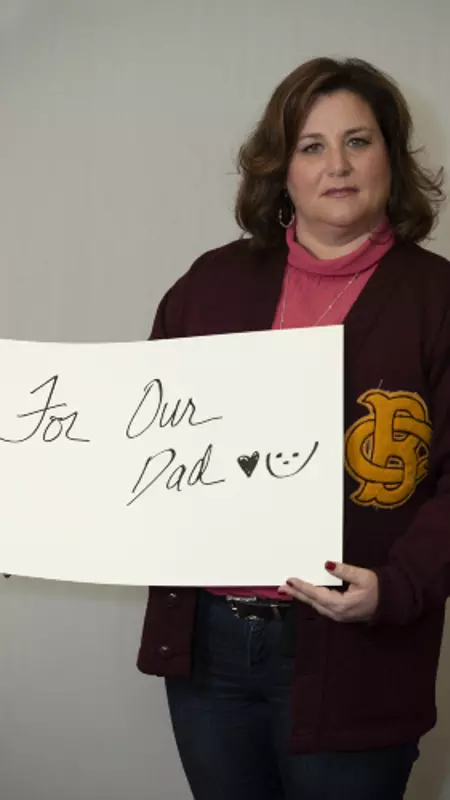

Julé Frechette’s #WhyCLF is for her father John Frechette, who she calls the warmest, kindest, most giving person and best dad to her and her two siblings. John was an offensive and defensive tackle for Boston College before being drafted in 1965 by the Boston Patriots where he played for a season. Frechette also spent a year with the Green Bay Packers playing for legendary coach Vince Lombardi. After a shoulder injury in 1967 ended his football career, he went on to have a successful business career working in labor relations. Signs of memory issues and mood swings began in his mid-50’s and continued to progress. Julé says as her father’s disease progressed, his sadness, frustration and inability to think clearly became more profound and caused him to withdraw and lose his “life of the party” personality. Frechette was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s Disease in his late 60’s and died in 2014 at age 71. Researchers at the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank later diagnosed him with Stage 4 (of 4) CTE.

“The differences came very strongly and very loudly after the last time he played football.”

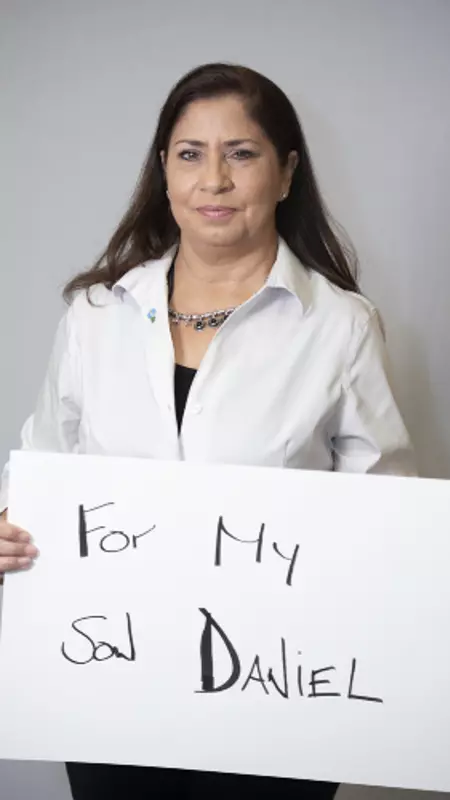

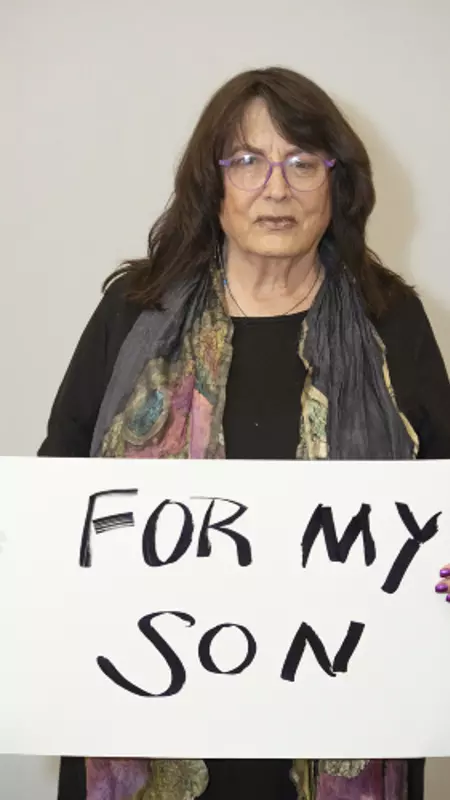

Diana Brett’s son Daniel stopped playing football after a concussion during a high school practice his freshman season. Then she learned he suffered nearly a dozen of concussions before that – and hid his symptoms so he could keep playing. Daniel was diagnosed with Post-Concussion Syndrome (PCS) and struggled with pain for the next 19 months of his life. In May 2011 he died by suicide at age 16.

Diana is passionate about educating all athletes to speak up about their concussions. She’s also empowering parents to be advocates for their children’s health so they know what to look out for when it comes to concussions. It’s her #WhyCLF.

Payton Mincey’s #WhyCLF is for her dad Daniel Brabham.

Daniel was an Air Force veteran, teacher, family man and an all-conference linebacker and fullback at the University of Arkansas before spending six seasons in the NFL with the Houston Oilers and Cincinnati Bengals. Brabham was a lifelong crusader for change. He fought to ban smoking in the workplace in Louisiana and founded the Louisiana Fisherman’s Forum. After his death in 2011 at age 69, researchers at the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank diagnosed him with CTE.

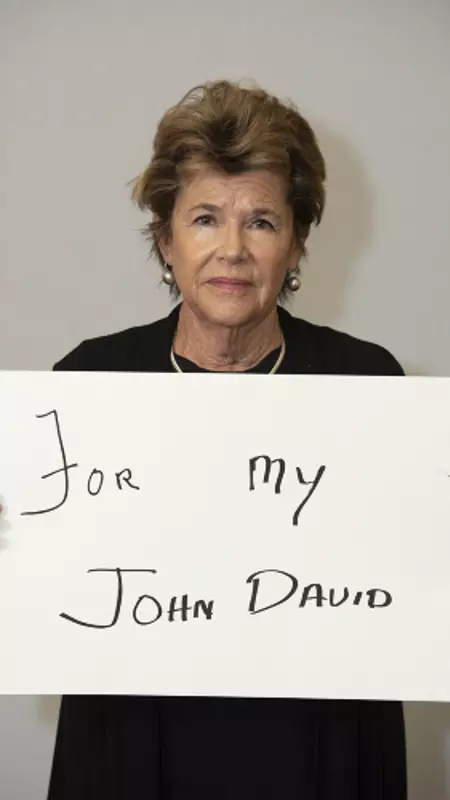

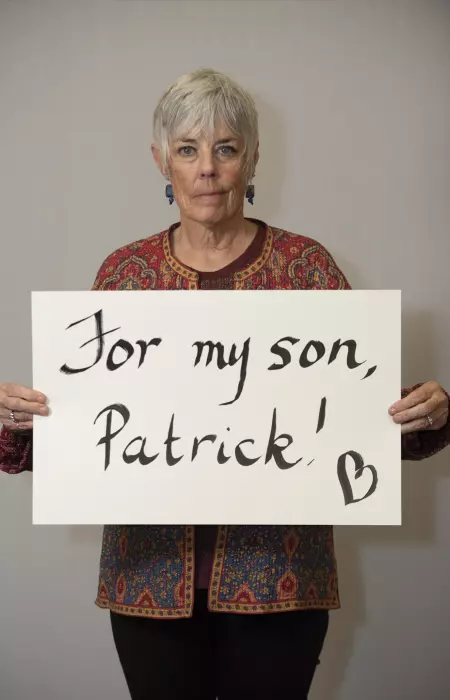

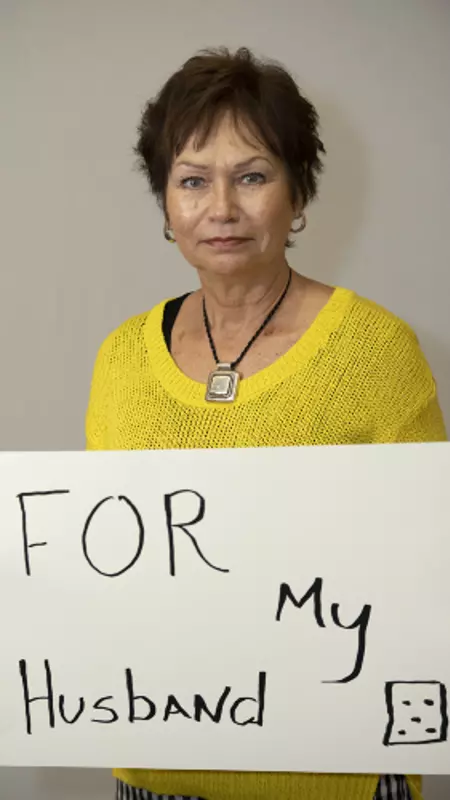

Tough, kind, and larger than life. An All-American football player for Boston College who spent three seasons in the NFL – Pat Frechette’s #WhyCLF is for her husband John David Frechette.

John was an offensive and defensive tackle who was drafted by the Boston Patriots in 1965. A shoulder injury ended his NFL career early, and he transitioned to life as a father of three working in labor relations. In his late 40’s, John started showing signs of depression, memory loss, and mood swings. In 2011 he was officially diagnosed with Alzheimer’s Disease. He died three years later at age 71. The Frechette family says they donated John’s brain to the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank to learn more about how to make the game John loved safer. Researchers at the Brain Bank diagnosed Frechette with Stage 4 (of 4) CTE.

“Everybody loved Austin. He had such an energetic personality and was able to make friends wherever he went.”

Michelle Trenum’s #WhyCLF is for her son Austin. Austin Trenum was a star student and athlete who played football and lacrosse at Brentsville District High School in Virginia. Austin suffered his first diagnosed concussion during his junior football season. A year later in September 2010, he suffered his second diagnosed concussion during a game. Austin took his own life 43 hours later. He was 17 years old. Michelle and her husband Gil donated Austin’s brain to the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank to help advance research about the link between concussions and suicide. They now honor Austin’s legacy by supporting other families who have lost a child to suicide after concussion.

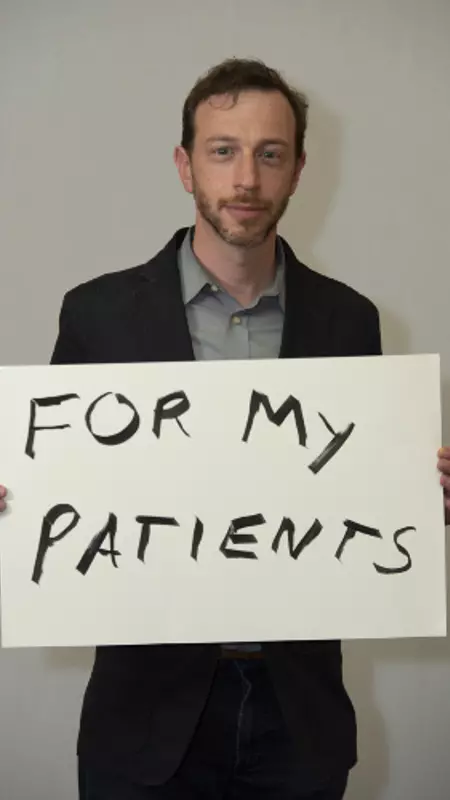

Why is Dr. Jesse Mez so passionate about his work? For his patients.

Dr. Mez is an important member of both the BU CTE Center and BU Alzheimer’s Disease Center research teams. He’s also an Assistant Professor of Neurology at Boston University School of Medicine. Dr. Mez is part of the team that interviews family members and caregivers of Legacy Donors to learn more about their lives and the symptoms they struggled with. His research is helping identify possible risk factors for CTE. Dr. Mez was the lead author on an October 2019 study that found the odds of developing CTE increase 30% for each year of tackle football played.

Quiet, deep, and strong – Joslyn Aitken remembers her son Devin Hands for his caring heart. He’s her #WhyCLF.

Devin grew up in Laguna Beach, CA where he excelled in every sport he played. He started tackle football at age 12 and cherished the “Tough as Nails” award he received for taking so many big hits. Devin loved the outdoors and worked hard to earn the prestigious Eagle Scout rank. Beginning around age 17, Devin struggled with headaches and mood swings. He died of a brain hemorrhage from a fall in 2013 at age 22. Joslyn donated his brain to the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank to help advance research about concussions.

“My favorite thing about him was his gentleness. They called him a Minnesota Monster on the football field, but he had a second side, a soft side, that I loved.”

Carolyn Lens says her #WhyCLF is for her sweetheart, her husband of 25 years, Greg Lens.

Greg Lens was a star defensive tackle at Trinity University before being drafted into the NFL in 1971. He played two seasons for the Atlanta Falcons. Lens also served in the U.S. Army, and went on to be a high school teacher and coach in Texas, a job his family said meant so much to him. Near the last decade of his life, Carolyn says she started to notice changes in Greg. He forgot directions to places he’d traveled to hundreds of times. He struggled to tell time. Then the paranoia set in – and Greg battled bouts of aggression and rage. Unable to stay at home, Greg moved in and out of several care facilities during the last years of his life. He died from pneumonia in 2009 at age 64.

Researchers at the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank later diagnosed Lens with Stage 4 (of 4) CTE.

Our co-founder and CEO Christopher Nowinski, Ph.D has endless answers for #WhyCLF.

Nowinski was a two-time All-Ivy defensive tackle for Harvard before wrestling in the WWE. His WWE career was cut short after a kick to the head led to Post-Concussion Syndrome (PCS). Nowinski recognized the desperate need for athletes to understand the serious consequences of concussion, and teamed up with his physician Dr. Robert Cantu to co-found CLF. He’s also a co-founder of the Boston University CTE Center and is driving us toward achieving our vision of a world without CTE and concussion safety without compromise.

Bunny Brabham’s #WhyCLF is for her late husband Daniel Brabham.

Daniel was an all-conference linebacker and fullback at the University of Arkansas before spending six seasons in the NFL with the Houston Oilers and Cincinnati Bengals. Brabham also served in the US Air Force Reserves and was a high school chemistry and math teacher. A lifelong change agent, Daniel fought to ban smoking in the workplace in Louisiana and founded the Louisiana Fisherman’s Forum. After his death in 2011 at age 69, researchers at the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank diagnosed him with CTE.

“He went from playing soccer every day, jogging every day, riding his bike, to being completely paralyzed.”

Patrick Grange loved soccer. Everything about it. His mom Michele says he was a natural athlete who was coordinated even as a toddler. He started heading soccer balls for hours on end when he was three years old. A star athlete in high school, Pat continued his soccer career in college playing for the University of Illinois at Chicago and the University of New Mexico. He also took his talents to a semi-pro team in Chicago. Michele says he suffered several concussions throughout his career. Then at age 28, he felt weak and knew something was wrong. He was diagnosed with ALS shortly after. Patrick Grange passed away 17 months later. Researchers at the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank later diagnosed Pat as the first former soccer player with #CTE.

Michelle says Pat was a humble, quiet kid, who courageously went public with his ALS diagnosis to help raise awareness for the disease. Now Michelle and her husband Mike honor Pat by sharing his story and advocating to remove repetitive head trauma from youth sports. It’s Michelle’s powerful #WhyCLF.

“He brought smiles to everybody’s faces and was a real inspirational guy who never met a stranger. Just an overall great dad.”

Sarah Naylor’s #WhyCLF is for her father Greg Lens. Lens was a star defensive tackle at Trinity University before being drafted into the NFL in 1971, where he played two seasons for the Atlanta Falcons. Lens also served in the U.S. Army, and went on to be a high school teacher and coach in Texas. Sarah says she first started noticing changes in his behavior when she would come home for breaks in college. He became forgetful and more reserved. Then the mood swings kicked in. By the last year of his life, Sarah recalls him as “the shell of emptiness.” Greg Lens died from pneumonia in 2009 at age 64 and was later diagnosed with Stage 4 (of 4) CTE at the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank.

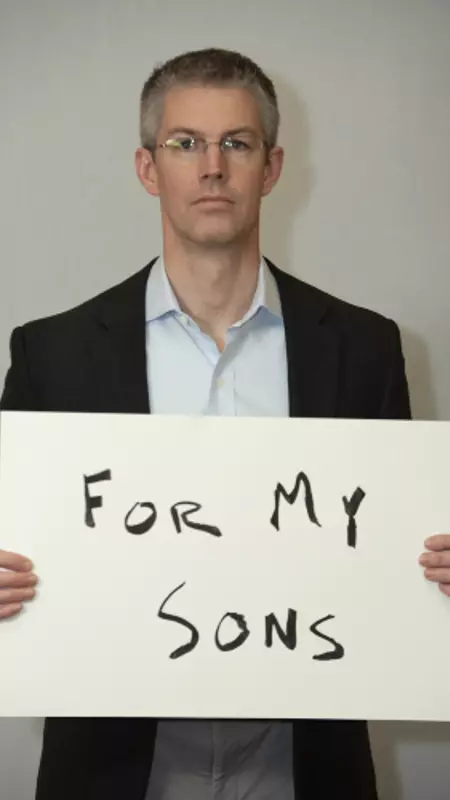

Dr. Thor Stein is dedicated to his work researching CTE so his sons will have a safer future.

Dr. Stein is a neuropathologist at the VA Boston Healthcare System and assistant professor of pathology and laboratory medicine at the Boston University School of Medicine. He is a part of the Neuropathology Core of the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank, where he analyzes the brain tissue of CLF Legacy Donors. The work of Dr. Stein and his colleagues is essential to what we do at CLF. Each new diagnosis furthers our understanding of concussion, CTE, and the effects of neurodegenerative brain diseases.

Scott Gilchrist’s #WhyCLF is for his dad Carlton Chester “Cookie” Gilchrist, who started experiencing behavioral symptoms around age 35. Cookie was known for his power and speed as a record-setting running back in the Canadian Football League and American Football League. Gilchrist won two AFL MVP awards playing for the Buffalo Bills in the 1960’s. After his football playing days ended, Cookie turned to a career in business. At home, Scott says the simplest things could make his father upset. He struggled with paranoia, impulse control, and became very reclusive. In the last year of his life he struggled with severe memory, judgement and problem-solving difficulties. He died in January 2011 at age 75. VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank researchers later diagnosed him with Stage 4 (of 4) CTE.

Scott says now that he has a better understanding of the disease, he has more respect and compassion for what his dad was going through, especially at such a young age.

“Dice was a man who believed that everyone he met held the potential to be his friend.”

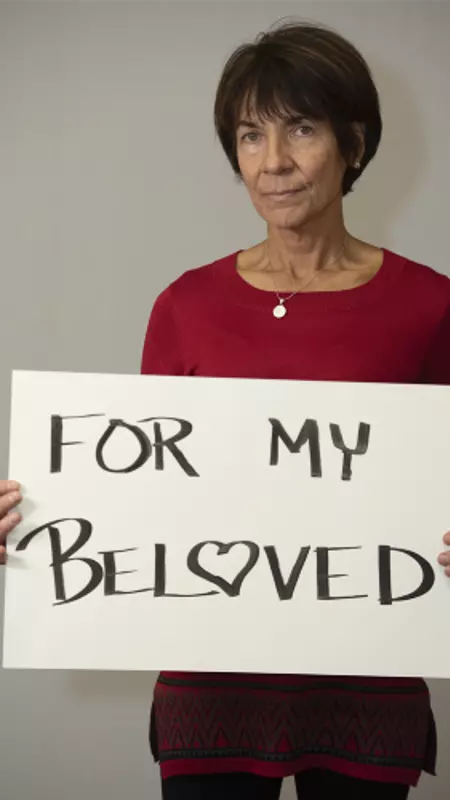

Elizabeth Allardice’s #WhyCLF is in memory of her late husband Robert” Dice” Allardice.

Born in 1947, Dice was a football player, wrestler, and boxer at West Point – The US Military Academy. In just one week playing at West Point, Dice suffered three concussions and week later, a broken neck. In 2006, Dice began showing bizarre behavior and struggled with cognitive issues. Those issues progressed over the next eight years before his death in November 2014. He was later diagnosed with Stage 3 (of 4) CTE at the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank.

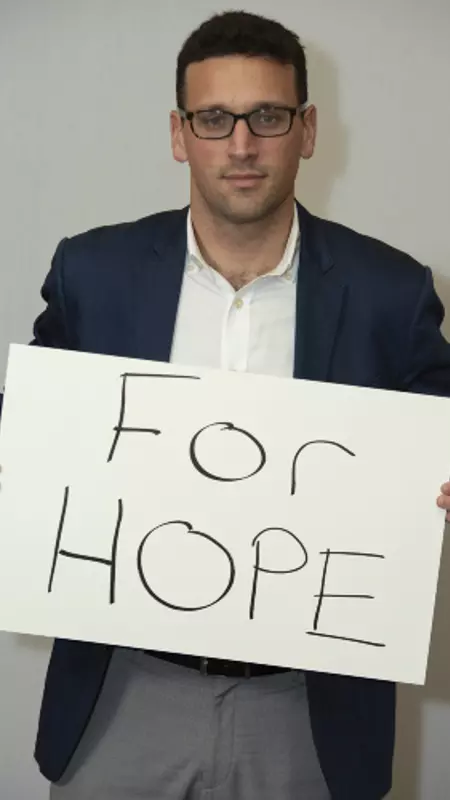

Michael Alosco, Ph.D. works to provide hope for those who may be living with CTE.

Dr. Alosco is a neuropsychologist and Assistant Professor of Neurology at the BU School of Medicine, where he also serves as the Co-Director of the BU Alzheimer’s Disease Center Clinical Core. His career has been devoted to investigating the risk factors and biomarkers of neurodegenerative diseases like CTE and Alzheimer’s, to help find ways to treat and eventually cure them. He works with the clinical research team at the Boston University CTE Center to learn from Legacy Donor families about their loved one’s history of head trauma, and the symptoms they experienced. This clinical report is presented alongside the pathological findings when the researchers inform families whether or not their loved one had CTE or any other abnormalities in their brain.

“He was not the person that we knew and loved. The disease took away his passions and his joy for life.”

Patty Pae was one of the caretakers for her father as he struggled with the debilitating symptoms of CTE for nearly the last decade of his life. The pain and suffering she saw him endure sparked her drive to help others experiencing the same with a loved one. It’s her #WhyCLF.

Patty’s father Dick Proebstle was a quarterback for Michigan State University’s football team in the 1960’s. Concussion-related issues forced him to stop playing after his junior year season. Proebstle went on to have a career in business before symptoms of CTE took over. In the last 20 years of his life he battled aggression, depression, paranoia, anxiety, along with failing executive functioning and speech. He died in 2012 at age 69. Researchers at the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank later diagnosed him with CTE.

“It was exhausting because you didn’t know which Kyle you were going to get. It’s just sad seeing your son change and be so sad.”

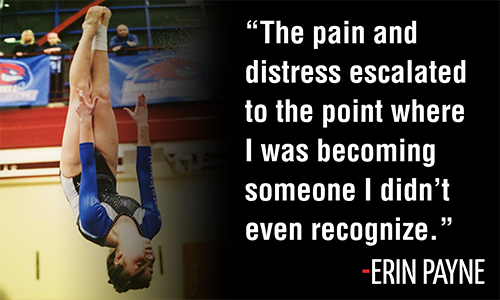

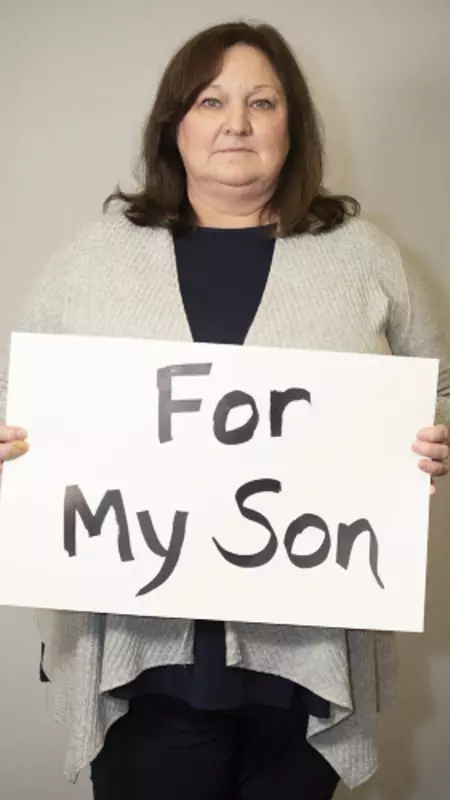

Beth Raarup’s #WhyCLF is for her son Kyle – who she saw struggle with mood swings and depression after a series of concussions at a young age. Kyle Raarup was a sports fanatic who loved playing hockey, football and baseball. Beth says Kyle was a happy kid who was always full of energy, before concussions forced him to quit sports in 8th grade. He was later diagnosed with Post-Concussion Syndrome (PCS). Treatments helped Kyle graduate high school and attend college, but he continued to suffer from anxiety, depression and memory loss. Kyle took his own life in November 2015 at age 20. His brain was later studied at the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank, where researchers diagnosed with him Stage 1 (of 4) CTE.

After Kyle passed away Beth and her husband Mike discovered Kyle liked to use the phrase ELE, or Everybody Loves Everybody, to promote a message of kindness. They say they are proud to honor his legacy of helping others by raising awareness about concussions and CTE.

Mary Hawkins’ #WhyCLF is for her late husband Ross “Rip” Hawkins.

Rip was drafted in the second round of the 1961 NFL Draft by the inaugural Minnesota Vikings team. After making the 1963 Pro Bowl, he retired from football in 1965 to pursue a law degree. He served the Assistant District Attorney for Fulton County, GA and coached high school football in Colorado and Wyoming. He retired to ranch in Wyoming and later became the Wyoming Department of Transportation commissioner and a local municipal judge. Late in life, Rip presented symptoms of Lewy Body Dementia. Researchers at the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank diagnosed him with Stage 4 (of 4) CTE after his death in 2015 at age 76.

“When he was 28 something went wrong. He came to me and said, you know what, I have no power in me. I can’t run, I can’t push off from my feet, I have no power. I’m weak.”

Mike Grange’s son Patrick was diagnosed with ALS at age 28 and passed away 17 months later. Patrick Grange loved the game of soccer. He started heading balls at age three and suffered several concussions during his successful playing career at the University of Illinois at Chicago, the University of New Mexico, and for a semi-pro team in Chicago. During the last year of his life, Pat courageously went public with his diagnosis to help raise awareness for ALS.

After his death, the Grange family donated Pat’s brain to the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank. He later became the first former soccer player to be diagnosed with #CTE. When you ask Mike Grange #WhyCLF, he says to honor Pat. Mike now advocates to make youth sports safer, so other kids don’t endure repetitive head trauma.

“Jeff was an amazing man. When he walked into a room people would stop and stare. He had an infectious laugh, and was just one of the most kind, loving men I had ever met.”

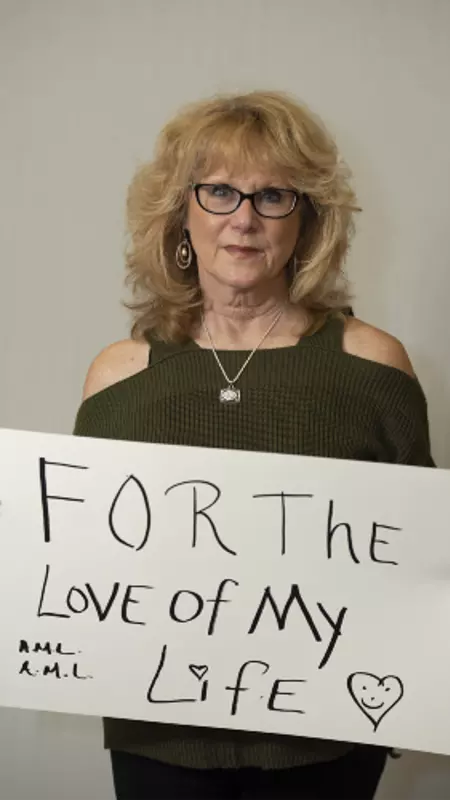

Brandi Winans’ #WhyCLF is for the love of her life, her late husband Jeff Winans.

Jeff was a star athlete growing up in Turlock, California and accomplished his dream of earning a scholarship to play football at the University of Southern California. Jeff won a national championship for the Trojans in 1973 and went on to play six seasons in the NFL. After football, Jeff became a champion for several local causes in Tampa Bay. But headaches, depression, emotional, and cognitive issues affected his decision making, temper, and memory before his death in December 2012. He was later diagnosed with Stage 3 (of 4) CTE at the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank.

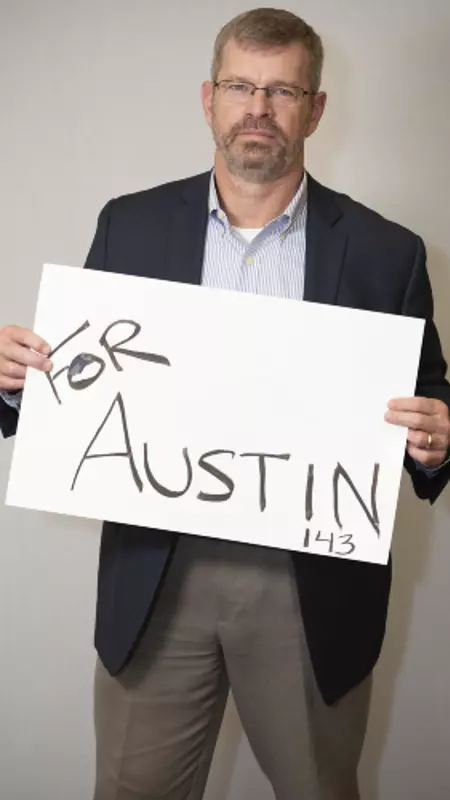

Gil Trenum is dedicated to our cause for his late son Austin Trenum. It’s his #WhyCLF.

Austin played linebacker and fullback as a senior on the Brentsville District High School varsity football team in Virginia. He was a star student who was beloved by his classmates for his vibrant personality. Austin suffered his second diagnosed concussion during a football game in September 2010. He took his life 43 hours later. He was 17 years old. Gil and his wife Michelle donated Austin’s brain to the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank to help advance research about the link between concussions and suicide. They now honor Austin’s legacy by supporting other families who have lost a child to suicide after concussion.

Lisa McHale became our Director of Legacy Family Relations after her husband, former NFL lineman Tom McHale, died tragically of an accidental drug overdose in 2008. Tom later became one of the first former football players to be diagnosed with CTE at the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank. In her role, Lisa is the liaison between brain donor families and the research teams, guiding families through every step of the donation and diagnosis process.

Lisa’s #WhyCLF is for Tom and the incredible role he played in helping the world understand the long-term effects of repetitive head trauma.