Posted: February 28, 2019

Matt is one of thousands of people who have pledged to donate their brain to CLF to support research. He shared his thoughts about Project Enlist, CLF’s program to advance research in the military community, during Brain Pledge Month 2019. Watch the video and read on:

Why is pledging one’s brain to research something that you’d like to see catch on among service members?

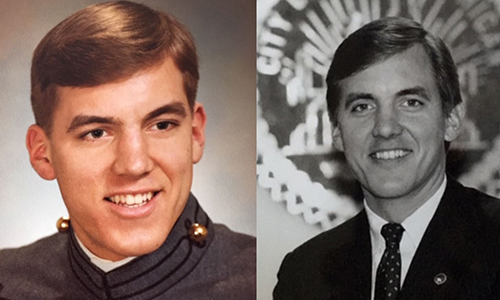

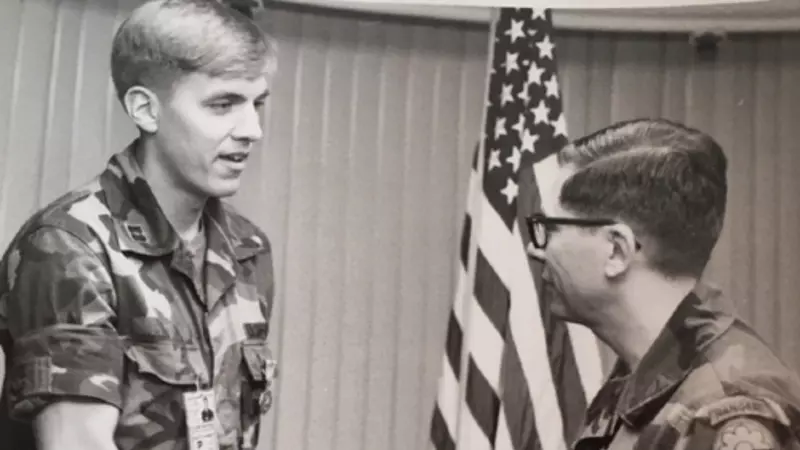

I’ve pledged my brain to CLF, and as you know, I’m a veteran. My former boss, and good friend, Bob McDonald, also a veteran, who was the Secretary of the VA, has pledged his brain as well. The more veterans we can inspire to pledge their brains – veterans who have typically played sports or who have been in combat – the more work we can do toward the advancement of vital brain research.

It’s seriously important to get as many veterans’ brains pledged as possible. It’s very similar to pledging your organs when signing for your driver’s license. It’s a really impactful and important thing to do for research; and I think every veteran should at least consider it.

Just to be clear, for this effort to be successful in the long run, we will also need to conduct research on brain specimens that have not been subjected to trauma – to act as a control group for the research. Every pledge counts no matter the exposure you have had to brain trauma.

What do you hope Project Enlist will accomplish?

Researchers have made tremendous progress learning about the consequences of brain trauma in various sports, but there is still so much more we need to know about TBI, and the causes of PTSD and CTE in veterans. It’s critically important that we learn what is unique about the brain trauma that many veterans are exposed to during military service. Through Project Enlist, we will mobilize the military community to support this research, and I hope it accelerates efforts to improve the long-term health and well-being of not only our veterans, but of Americans in general.

The VA is a collaborator with Boston University and the Concussion Legacy Foundation on the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank. What did you learn about the VA’s research capabilities while you were there, and how did you eventually get involved with the Concussion Legacy Foundation?

First of all, people know very little about the monumental research that is done at the VA, and it’s not just for veterans. The VA has conducted major pioneering heart studies, performed the first liver transplant, developed the nicotine patch, and the list of discoveries and major breakthroughs in healthcare go on and on – in fact, doctors working for the VA have received several Nobel prizes, and numerous Lasker awards. Ironically, major innovation and game-changing research are not what the VA is known for, but the VA and its brilliant researchers demonstrate these unique and significantly impactful qualities every day.

I got involved with CLF a few years ago while serving the VA under then Secretary Bob McDonald. I became intensely interested in brain science because so many veterans suffer from brain injuries and from PTSD. We thought it was critically important to explore, and better understand, why these phenomena were happening at higher rates in the military. So one of the things we (the VA) did was to start an event called “Brain Trust.” We gathered the best and brightest from all over the country in brain research, and brought them all together. We wanted to create an environment conducive to partnerships and creative thinking. During this time, Bob Costas introduced me to Chris Nowinski. Of course Chris and the Concussion Legacy Foundation really stepped up to the plate for Brain Trust. I was so impressed by Chris, his team, and the work CLF has done, that I eventually worked with Chris to come on to CLF as an informal advisor. Ultimately, Chris and the board asked me to join in a more official capacity as a full-fledged Board member. I’m extremely honored to be part of the CLF team.

What do you hope to accomplish as a member of CLF’s Board of Directors?

First and foremost, my focus will be on improving the lives and long-term health and well-being of veterans. I hope my experience and connections in the military and veteran community will help push research forward through programs like Project Enlist, and help enhance the work CLF is already doing for veterans and their families.

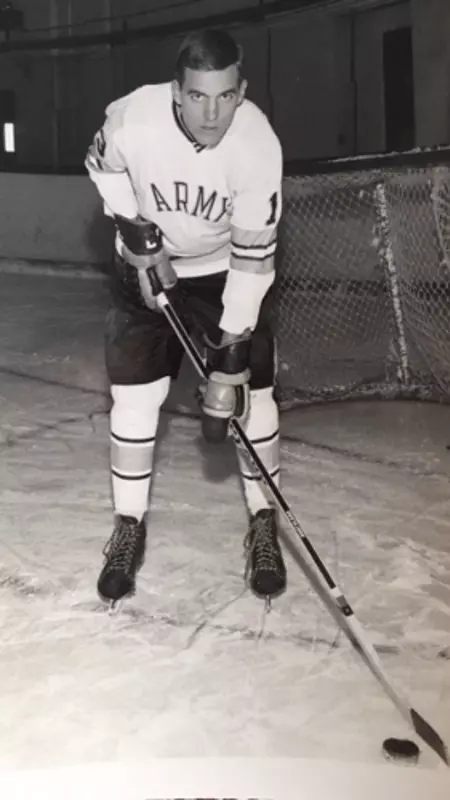

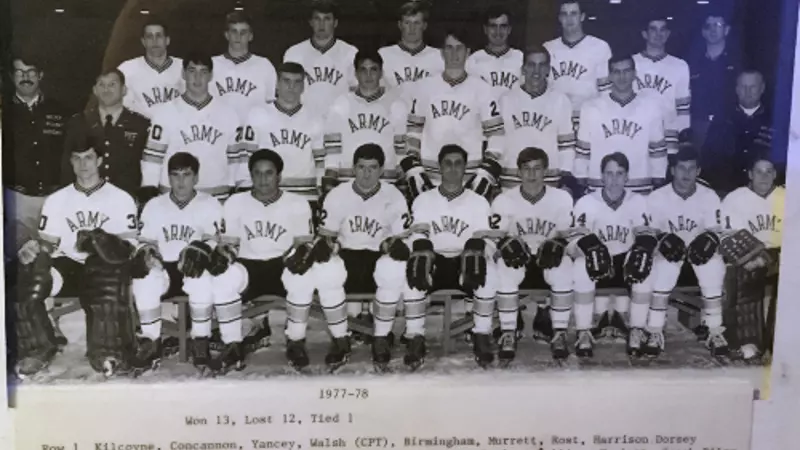

The awareness of concussions and CTE right now is probably higher than it has ever been. Did you ever think about all those hits adding up while you were playing hockey for West Point or during your military service?

When you’re young, of course, you think that you’re invincible. I never really thought of the hits to my head as a boy or as a young man, but I think about it now – much more frequently. And the idea of invincibility, which is a common theme by the way, as our brain donor families talk about their loved ones – many of whom were professional athletes – and who ultimately suffered the consequences of CTE. This feeling of youthful invincibility is exactly why we need to raise awareness with young men and women, as well as their families – before CTE can take hold as a result of repeated hits to the head.

And as you translate this to military service, and the greater vulnerability to our military men and women in combat zones as they serve our country, it’s critical that we better understand what is really happening inside the brains of these brave service men and women as a result of exposure to explosions, blast, and the impact of trauma. We are only in the embryonic stages of brain research, and we need to learn so much more about how this trauma could be connected with PTSD, and other possible psychological manifestations of CTE. We have a long way to go, and the only way we can make progress is one important step at a time.

You are a prime example of a successful transition from the military to civilian life. What allowed you to make that transition so smoothly?

I’m not sure… I guess I’ve been very lucky to have had a very supportive family around me since I was a kid; and have been, and continue to be, surrounded by great people – wonderful employees, terrific bosses, talented colleagues, and extremely helpful and caring mentors.

Join Matt Collier and pledge to donate your brain.