James “Jimmy” Carroll

Roger Shoals

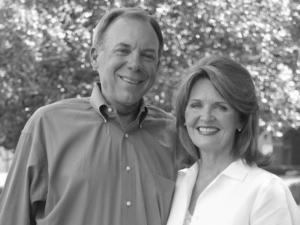

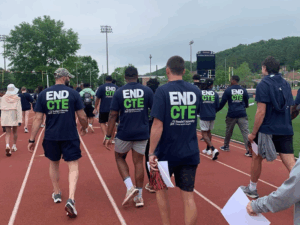

The Pat Sullivan Family Race to End CTE: Honoring a Football Legend

The first Race

Jean Sullivan had never organized a 5K. She couldn’t remember even participating in one. But as she considered how to honor her late husband, Heisman Trophy winner and beloved coach Pat Sullivan, Jean knew she, her family, and her community could make an impact.

“My advice is really just to make the determination to do it and then just start talking to everybody,” Jean said. “It comes together easier than what you think. It is time-consuming but well worth it.”

In 2024, Jean launched her first Race to End CTE campaign, an online fundraiser leading to a 5K walk in memory of Pat, her husband of 50 years who gave everything to his teams and his players. More than 200 people walked together at Samford University to honor not only the legendary Auburn quarterback, but all former athletes, veterans, and families affected by CTE.

Jean was inspired by her experiences building community at CLF’s biannual Legacy Family Huddle in 2022 and 2024. Meeting family members who had faced similar challenges not only validated her own experience, but their strength and resilience galvanized her to share her story and involve her Alabama community in the Race to End CTE.

“It was eye-opening to hear from these families and researchers,” Jean said. “Families talked about sharing our stories and encouraged us to have our own Race. Even though it was just a month or so away [in 2024], I decided maybe we could have one in Birmingham.”

The support shown to the Sullivan family in Birmingham was immediate and impactful. That first year, Jean’s campaign raised more than $82,000. In 2025, she set an even bigger goal — and hit it. Her campaign became the first to raise $100,000 in a single Race to End CTE.

As its name suggests, the Pat Sullivan Family Race to End CTE centers a family’s spirit — a family with strength in numbers. From Jean’s 2-month-old great-granddaughter to her 98-year-old father, these events have brought together five generations to support CLF in honor of their treasured patriarch.

Helping other families

Jean says this passionate work on behalf of CLF is about sparing future football families from the struggles hers faced in Pat’s final years. She encourages everyone at her events to share the CLF HelpLine with those struggling with concussion or CTE symptoms.

“We know there are others that are suffering in silence, and their families and their children are suffering with them and they don’t know where to turn for help,” she said. “We were one of those families.”

On top of promoting awareness, prevention, and the HelpLine, Jean uses her campaign to explain the role of research in the Race to End CTE. She lets her supporters know their donations are helping researchers at the BU CTE Center make breakthroughs.

“It gives me hope when I hear that they’re working on finding a cure for diagnosis in the living through biomarkers,” she said, referencing studies like BANK CTE. “Once they can detect it, then they hopefully can find a cure for it. And then with education, people can learn to take better care of their brains.”

With two wildly successful fundraisers under her belt, Jean says she feels deeply grateful and motivated to build on this momentum in Alabama and beyond. Her Race to End CTE is far from over.

“I’m appreciative of everyone that has participated in the Race, whether it be online or here in person,” she said. “If they can all go out and share what they have learned about CTE, that would be very important to me.”

John Krouse

Gregory Larson

Abner Haynes, Sr.

Jim Huge

Bruce McMillan

A Talented Athlete Since Birth

Bruce McMillan was born on June 26, 1950, in Northern Ontario, where hockey was a way of life. He started playing the sport at an early age on outdoor rinks, and his athleticism was apparent even during youth. Bruce played Junior A hockey with the Soo Greyhounds, then picked up football in junior high school. After playing both sports at Mount Allison University, he was the first draft pick for the CFL’s Ottawa Roughriders in 1973.

Once Bruce’s playing days were over, he worked various jobs including high school teacher and principal, appraiser, real estate agent, and ice rink manager. In his free time, Bruce was an avid tennis player and fisherman. But his most important role was that of a husband and father to four wonderful children. The love he showed to his family had no boundaries. He was blindly loyal, fiercely intense, and exceptionally hard working with a high EQ.

Bruce’s competitive spirit was matched only by his commitment to our local community. He continued to stay involved in sports by coaching numerous teams in hockey, football, and basketball, sharing his knowledge with countless young athletes. Bruce’s dedication to mentorship throughout his life made a lasting impact on all the youth he worked with, instilling them with confidence, resilience, and purpose.

The Effect of Brain Injuries

Bruce had a number of concussions before the age of 18; our family and friends have counted at least 11. That number grew as he continued to play contact sports in university and professionally. He experienced headaches, but never migraines. Throughout his life, Bruce also suffered from bleeding ulcers; a result, perhaps, of trauma from his childhood.

We really noticed Bruce starting to act impulsively in his late 40s. By the time he turned 60, his loss of memory was evident, and his mood and behavior changed drastically. He became aggressive, totally egocentric, and was easily angered. During our daily five mile walks, Bruce would get in the faces of strangers and frightened a number of people. His driving was erratic and he became involved in a fender bender, forcing us to take his license away.

Bruce had trouble staying still and would wander around, always trying to escape from our home. We had to keep a GPS device on Bruce at all times, and eventually even put locks inside our doors, requiring codes to leave.

Bruce’s decline affected our family greatly. His grandchildren were nervous to be around him, even fearing him at times. Some days he would be the fun Papa, but mostly he would have absolutely no patience with them. It was heartbreaking to watch.

For 13 years, I tried my absolute hardest to keep Bruce safe at home, until he was hospitalized for the last three weeks of his life. He became out of control and needed more help than I was able to provide. He had to be restrained in a bed to keep from escaping and potentially injuring one of the medical staff.

A Continuing Legacy

We found out about the Concussion Legacy Foundation a few years ago while trying to find help online. I signed up for their emails and went through all their resources, becoming convinced Bruce was suffering from suspected CTE. I saw the decline of my mother from Alzheimer’s and my husband’s journey seemed so different.

I talked to my gerontologist about CTE but somehow found myself explaining the disease to him. He couldn’t explain why Bruce’s CT scans didn’t show much – just a small bit of atrophy, nothing else. I always felt I needed to know if Bruce had the disease, so I called the UNITE Brain Bank on the morning of his death, September 23, 2024, and their staff took over the whole process. It was an incredibly seamless experience.

In August 2025, Dr. Ann McKee contacted our family to confirm Bruce’s diagnosis: he had stage 4 (of 4) CTE. We knew it was severe so this diagnosis did not come as a surprise.

Through Bruce’s Legacy Story, I’d like everyone who met him to know he was a wonderful person. He unfortunately was not able to properly control his thoughts and actions during the last 13 years of life. It wasn’t him; it was the disease taking over. Our family repeated this constantly to each other when he was being difficult. We miss Bruce very much and I know he’d be so proud that his final legacy as a brain donor will contribute to future CTE research.

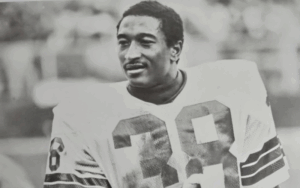

Cornell Webster

Honoring the Man Behind the Number

Cornell Webster’s life was a tapestry woven from unwavering determination, athletic greatness, and a profound love for his family and community. Born in Greenville, Tennessee, to Richard and Margie Webster, Cornell’s story began with the values and discipline instilled by his parents. His father was not only a guiding force but also his very first football coach, laying the foundation for Cornell’s future.

Cornell rose to national recognition as a formidable NFL player, but those who knew him best understood his most significant achievements lived far beyond the field.

The Making of an Athlete

The Webster family cherished athleticism and excellence which is why Cornell’s talent wasn’t a surprise — sports ran deep for the Websters. One of his brothers played basketball at Whitworth College in Spokane, Washington, while another brother attended San Jose State as a wide receiver and in high school, set a long jump record of 24 feet 9 inches.

Cornell was a standout at Garey High School in Pomona, California, where he played tailback and safety on the football team. As a senior, he averaged over 13 yards per carry and quickly gained a reputation for being perhaps the best all-around athlete in the region.

College soon followed, and Cornell attended Scottsdale Junior College in Arizona, where he was a Junior College All-American in 1973, intercepting an incredible 11 passes that season. He then transferred to UCLA, where he initially played as a split end. However, coaches soon recognized his defensive instincts and moved him to cornerback, a decision which would shape his later playing career. Cornell finished his collegiate career at the University of Tulsa, where in 1976 he earned All-Missouri Valley Conference honors as a defensive back.

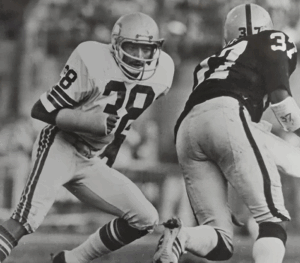

NFL Career: Grit and Glory

Cornell’s path to the National Football League was earned through grit, sacrifice, and sheer will. He was considered by many different teams including the Los Angeles Rams, Atlanta Falcons, Washington Redskins, San Diego Chargers, Cleveland Browns, Baltimore Colts, and even teams in Canada, before finding a home with the Seattle Seahawks. He proudly wore jersey #38.

At just 22 years old, Cornell quickly became a key player for the Seahawks, standing out not only for his skill but also for his poise. He was surrounded by former Tulsa teammates such as Steve Largent, Rick Engles, I.V. Wilson, Steve August, and his former Tulsa coach Jerry Rhome. This circle of familiarity made Seattle feel like home. Known to teammates as “C” or “C-Dub,” Cornell once said, “I just like the Seattle program.”

Cornell’s impact was immediate. He was named Player of the Week following his outstanding performance against the Pittsburgh Steelers and received game balls for his contributions in matchups against the Chicago Bears, Atlanta Falcons, and Oakland Raiders.

As an athlete, Cornell exemplified mental toughness and physical excellence. His sharp instincts, leadership, and relentless energy made him a reliable and respected force on the field. Every game he played wasn’t just about performance — it was about heart, pride, and inspiring others through action.

Family, Community, and Personal Passions

Outside of his athletic pursuits, Cornell was a dedicated husband, father, sibling, and friend. He married Angelia (Jan) Webster, with whom he established a blended family consisting of four children: Roque, Chanta, Glen, and Mercedes. Their legacy of love is further reflected in their 12 grandchildren and four great-grandchildren.

Together, Cornell and Jan shared a passion for travel and discovery. They embraced adventures near and far, often accompanied by Jan’s mother, Dr. L. Toby Earles. The trio presented workshops and seminars to various organizations, including rookies for the Seattle Seahawks. Their message of positivity, inspiration, and character-building even took them to Brazil, where they were welcomed by communities eager to learn from their experience.

Cornell was known for his kindness, humility, and wisdom. He gave back freely, mentoring young athletes, supporting local initiatives, and offering encouragement to those in need. His belief in the power of education, discipline, and second chances shaped his interactions with everyone he encountered.

Decline in Health

In his later years, Cornell began to experience troubling symptoms which we suspect were due to Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE), a degenerative brain disease linked to repeated head trauma. As his condition worsened, he began to have issues with his memory, behavior, and daily functioning.

One day, Cornell left home to go to the store and didn’t return. At first, Jan waited, thinking he might be delayed. But after 30 minutes passed, she became concerned. Panic set in as she called local hospitals and checked all the places he typically visited. No one had seen him. She stayed up all night, consumed by worry. The next day, she contacted local authorities and filed a Silver Alert.

Soon after, a nurse recognized Cornell from a previous hospital visit. He was admitted under the designation “John Doe.” Jan rushed to the hospital, heart pounding, and found him confused and disoriented. That day marked a significant change.

As Cornell’s condition declined, the Webster family became fierce advocates for awareness and research around CTE. They stood by him every step of the way, determined to use his story to spark change. Though his brain could not be tested after death due to life support measures, his journey has already contributed to the growing national dialogue around player safety and long-term health.

Legacy and Remembrance

Cornell Webster’s legacy is one of strength, courage, and humanity. On the field, he was a master of his craft. Off it, he was a man of grace, principle, and compassion.

He is remembered not only as an elite athlete but as a devoted husband, father, grandfather, and friend. He inspired everyone who had the honor of knowing him. His life continues to influence discussions around athlete health and mental wellness.

Ultimately, Cornell’s story reminds us that greatness is not measured by trophies or statistics alone—but by how we love, how we lead, and how we rise in the face of adversity. His life is a powerful testament to faith, perseverance, and the lasting impact of a man who gave all he had to everything he loved.