Allen Way

Al Way was a quiet, kind, humble man, to whom I am proud to say I shared 50 years of marriage. I met Al while in college at the University of Iowa. We married before our senior year and upon graduation he received his orders that he would be serving in the Army for the next two years of his life. He was outstanding trainee in basic training and then Leadership Graduate from Non Commissioned Officers school at Ft. Benning Georgia. He served as a Platoon Sergeant with status of E6 in the Infantry. His field of duty was predominately Ahn Khe Vietnam. During his service he experienced blasts from mortars, claymores, and bangalore torpedoes. He endured a twenty-foot fall from a cliff into a rock filled river and survived it, to get up and keep moving through the jungle. He returned home after his eleven-and-a-half-month deployment, to a new four-month-old daughter so he took on his new role immediately. Like many others returning from Vietnam, he carried on and went about the business of taking care of his family then welcoming another baby, a boy, followed by another daughter. Al excelled at all areas of his life, including serving his State of Iowa as the Director of the State Crime Commission, until he decided to strike out and run his own business as a beer distributor. He served his community as a City Councilman, volunteer for his children’s school, church and countless other organizations.

When he returned from Vietnam there were some more subtle personality changes, but you would expect this from someone returning from combat duty. I would not know for several years later some of the traumatic experiences, both psychological and physical, that he had experienced. When Al started therapy at our local VA clinic he shared some of what he and others in his company had endured.

After retirement I noted increasing depression and anxiety in Al. We then were later blessed with a Veteran’s Clinic opening in our community. He started to receive service when he needed it most; medications, one on one counseling, and a PTSD group. Once again, he volunteered at the clinic to help others who were struggling as he was. A few years later there were CT scans which found a Traumatic Brain Injury. His depression increased as time went on, but he was sharing more of his experiences. He had increased paranoia, flashbacks, and night terrors. He had great difficulty remembering names, schedules and directions. He was a great woodworker, but it became a task for him to build anything. He would measure, re-measure, give up and try again. These were all things that came so easy to him in the past. Even with all the supports and numerous evaluations he seemed to be getting worse. He lost his balance on more than one occasion and would have falls that resulted in the need for emergency room visits and stitches.

On the evening of August 28, 2017, after helping me prepare supper, he washed dishes, made coffee for the next morning, and while I was gone from the house on a short walk, he took his life. I had thought that a man of his 71 years would not have the energy to do this, but I was wrong. There were no unusual behaviors on that day which would have warned me or anyone else he talked to that day.

After Al’s suicide, the deputy State Medical Examiner at the Iowa Department of Public Health called and suggested that we consider donating Al’s brain to the Boston University CTE Study. My three children and I did not hesitate to say yes. We went through three interviews, of which there were two conference calls and one written questionnaire. These were followed by a consensus conference with both the medical team and the psychological team. I was fearful that they would talk about my husband as if he were a clinical study, a file folder. We were comforted by the respectful way they discussed Al and his history. The staff at BU spoke of him as a person, who was loved with a story prior to being ill, a loving son, brother, husband, father of three and grandfather of nine. My family and I have great respect for all members of the research team. They were honoring Al in this process, not analyzing him. The findings were that my husband, Al, had stage III/IV Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE). Now we know how very much he was struggling but kept going for his family as long as he did.

He continues to help others as he did in his earthly life and we are all so proud of him and honored that he is now part of the study. The CTE study was part of our healing during our time of grief. Despite all the heart break and trauma, my three children and I are greatly blessed to have had him for so many years.

Zachary Weber

Bernard Webster

Timothy Webster

George Wells

Ralph Wenzel

Ralph Wenzel was an 11th round pick in the 1966 NFL Draft, and played guard for seven seasons with the Pittsburgh Steelers and the San Diego Chargers, where he estimated that he suffered more concussions than he could count. After football, Wenzel went on to coach football at the college level, but began suffering from significant memory lapses and cognitive problems in 1995 at age 52. His symptoms worsened to the point that he could no longer work, communicate, or feed himself and he was diagnosed with early signs of dementia at 56. Wenzel couldn’t drive or read a book by the early 2000’s, became dependent on a caretaker by 2003, moved to a full-time facility for dementia care in 2007, and had lost the ability to walk by 2010.

While Wenzel was losing his fight with dementia, his wife, Dr. Eleanor Perfetto, was a vocal advocate for the long-term effects that her husband and other former NFL players were experiencing. By publicizing her husband’s drastic decline, Dr. Perfetto, a former CLF Board Member, was instrumental in causing the NFL to change some of its safety policies and increasing public awareness of CTE and other long-term damage. Below, Dr. Perfetto tells Ralph Wenzel’s story.

William Wesley, Sr.

Charles White

Jesse Whittenton

Jesse Whittenton was born in Big Spring, Texas. He was a star athlete at Ysleta High School in El Paso and a highly sought-after recruit by many college coaches. He attended Texas Western University (now UTEP) and littered the school’s record books. In the 1955 Sun Bowl, the Texas Western Miners upset the heavily-favored Florida State Seminoles thanks to a legendary performance from Whittenton.

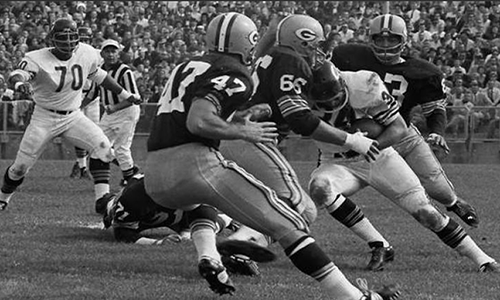

Whittenton was drafted by the Los Angeles Rams in 1956 and joined the Packers in 1958. Coach Vince Lombardi arrived in Green Bay the following season in 1959 and immediately made his presence felt.

Lombardi turned the then-woeful Packers into NFL champions in 1961 and 1962 and saw something special in Whittenton.

Lombardi once wrote Whittenton was “as close to being a perfect defensive back as anyone in the league… he can run with any halfback or receiver in the league and… he is a great student of opponents. He has studied everything about all of them, including the expressions on their faces that, when they come up to the line, may tell him something about what they are going to run.”

Whittenton was at times the perfect pupil, but at others he couldn’t shut off his jokester nature. In one of the two Pro Bowls Whittenton played in, his teammates were betting that no one would do the popular dance “The Twist” during the nationally televised game. Whittenton took the bet and twisted as his name was announced. He felt the wrath of Lombardi, who was also his Pro Bowl coach. Lombardi initially threatened to fine Whittenton $6000 for the dance, but Lombardi himself tried dancing while on vacation in Italy, realized the humor of the act, and reduced Whittenton’s fine to just $200.

Whittenton played in an era where concussions weren’t in the football lexicon. He swore he never suffered a concussion in his career, but then he would reminisce about getting his “bell rung” and returning to the game as soon as he came to.

Whittenton intercepted 20 passes in his seven seasons with the Packers, cementing his legendary status among Packers fans and his former teammates. Even decades after Whittenton retired from football, security guards at Lambeau Field would hug him when he returned for alumni weekends.

After football, Whittenton, who had taken to golf in college, returned home to west Texas and started his second athletic career as a golfer on the PGA Senior circuit. He and a cousin bought El Paso’s Horizon Hills Country Club in 1965. There, Whittenton hired a young man named Lee Trevino to serve as a bag boy for the course. A few years later, Trevino was in the midst of a Hall of Fame golf career and became Whittenton’s business partner.

After Jesse Whittenton’s football career ended, he (left) and future Hall of Fame golfer Lee Trevino (right) became friends and business partners.

Whittenton golfed every day for the rest of his life. The course was an outlet for his constant itch to be outside in the world. He was only able to sit still inside if a John Wayne western was on TV. On the course, his magnanimous personality was on full display.

“He just wanted people to be happy. He’d play golf with anybody,” said Barbara. “He didn’t care if you were a 40 handicap or you were a one handicap, really. He enjoyed it and he didn’t care.”

Whittenton always had dogs in his life, often by the same name. There were several Storm’s and always a Sheba. When a prior Sheba died young, Barbara saw Whittenton cry for the first and only time in their lives together. Whittenton got a new Sheba, who, along with Buster, followed Whittenton around the golf course like foot-tall furry caddies and slept with him at night.

In 2004, Whittenton and Barbara moved to the Sonoma Ranch golf course in Las Cruces, New Mexico. The two of them golfed and traveled together, with Whittenton still repairing clubs and helping at the course.

Five years later, Whittenton was diagnosed with throat cancer. The prospect of becoming a burden upset him.

“Why would I go through treatments when I’m going to die?” Whittenton asked his doctors.

Whittenton’s cancer treatment spotlighted his growing memory loss. He frequently forgot chemotherapy appointments or got lost during drives he’d made dozens of times.

The memory loss was so stark that friends of the Whittentons assumed it was just joking from the same man who did “The Twist” on live TV nearly 50 years earlier.

Whittenton was triumphant in his first bout with cancer. His memory continued to fade but the cancer was in remission.

He survived feeling like a burden through the first diagnosis, but he was crushed by a second terminal cancer diagnosis in March 2012.

On May 21, 2012, Barbara was in El Paso and Whittenton’s friends were scheduled to take him to an appointment. Before they arrived, Whittenton called a neighbor and instructed him to call 9-1-1 at 3PM. The neighbor didn’t wait that long.

By the time the ambulance arrived, Jesse Whittenton had taken his life. He was 78 years old.

The following day, Barbara received a call from the Las Cruces medical examiner. Researchers at the UNITE Brain Bank in Boston were requesting to study Whittenton’s brain.

“I said yes without hesitation. It was something I needed to know. I think everybody needs to know,” said Barbara.

Brain Bank researchers diagnosed Whittenton with Stage 3 (of 4) Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE). The diagnosis brought comfort to the Whittenton family. Rather than being a victim of dementia, something had caused his late-life memory loss and occasional outbursts.

At his funeral, former teammates told tales of Whittenton’s legendary kindness and humor. He was a beloved husband, father, and grandfather, as his grandchildren adored his playful spirit and ability to make them laugh.

Barbara has golfed only once in the seven years since Whittenton passed away. Sheba and Buster are her last link to the man she loved so deeply. They still sleep on his side of the bed.