Jay Wilkerson

Ben Williams

“I think Ben got up that morning thinking he could cook.”

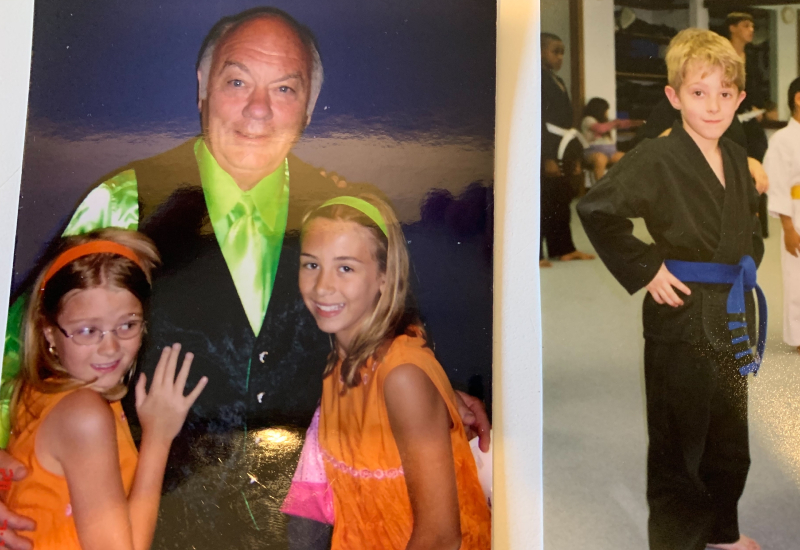

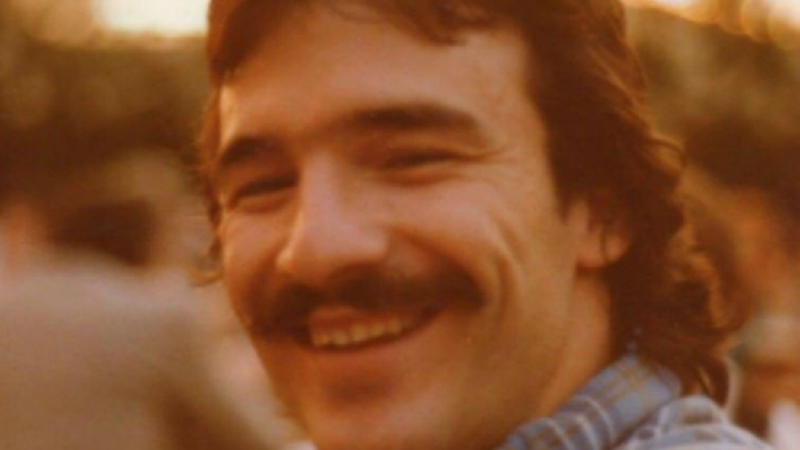

In October 2019, Linda Williams’ husband Ben Williams had just returned to their home in Jackson, Mississippi from a reunion with other Buffalo Bills alumni. Linda says Ben, 65 at the time, came back feeling like his younger self.

“He was stuck in that time period of back when he played football,” said Linda. “I couldn’t get him back. I tried to get him back, to talk about ‘now.’”

30 years earlier, Ben was the quintessential morning person and the engine of the family – often making breakfast for he and Linda’s three children and getting the family’s day started. But the Ben that woke up with intentions of making breakfast in October 2019 was no longer capable of doing much of anything by himself.

Linda woke up that morning to the sound of their dog barking, which was normal. The smoke she smelled in the hallway was not. She quickly realized Ben’s attempt to cook had gone disastrously wrong. She rushed to get them both out of their house while neighbors called the fire department. Once outside, Ben and Linda watched their house burn down.

“That didn’t faze him that much,” said Linda. “At that point, he was out of it.”

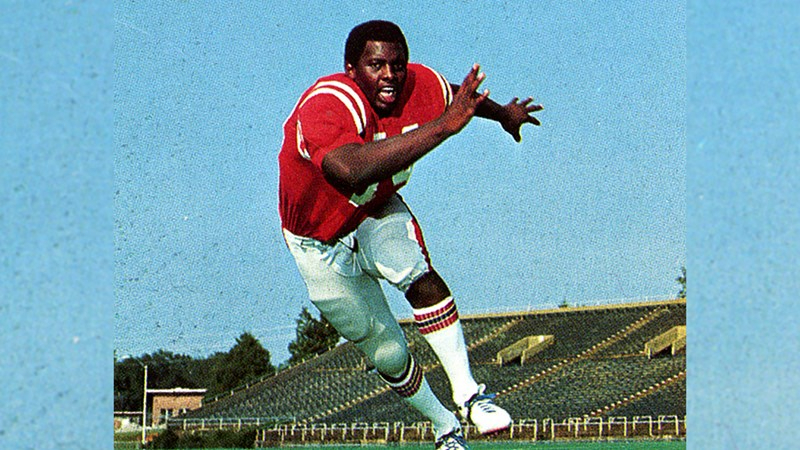

Mr. Ole Miss

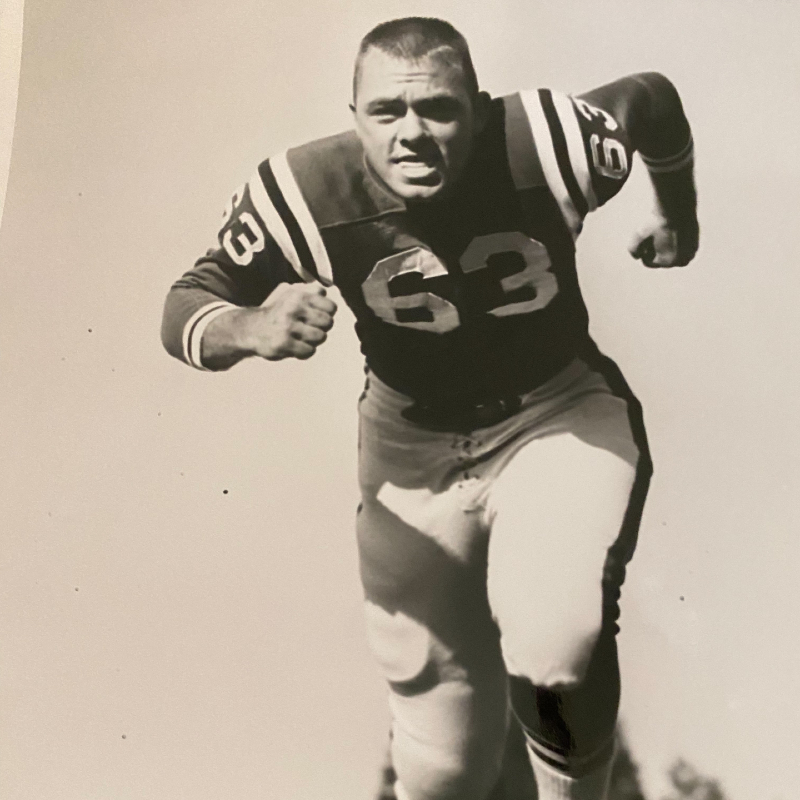

Born on September 1, 1954, Robert Jerry “Ben” Williams grew up in Yazoo City, Mississippi. He and James Reed were the first African American student-athletes to sign football scholarships with Ole Miss in 1971.

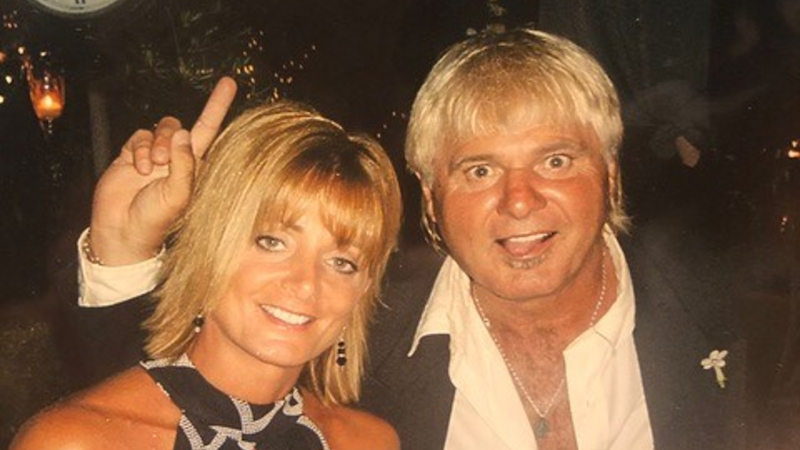

Linda met Ben her freshman year at Ole Miss. Ben showed an interest in Linda, but he was two years older than her. She was weary of upperclassmen and didn’t care about football in the slightest. But Ben’s nickname – “Gentle Ben,” after the titular character from the hit 1960s TV show – was no misnomer. She eventually gave in to his persistence and the two started dating.

“From the time I met him, he was always helping people,” said Linda. “He was very outgoing, real nice, and laughed a lot.”

Ben was a standout in every way at Ole Miss. He earned first team All-American honors as a defensive end in 1975, was elected as the first African American “Mr. Ole Miss” in school history and earned his degree in Business Administration from the school in 1976.

The Buffalo Bills selected Ben in the third round of the 1976 NFL Draft. Ben and Linda married that same year before making the nearly 1,000-mile trek north from Oxford to Buffalo.

“Dollar Bill”

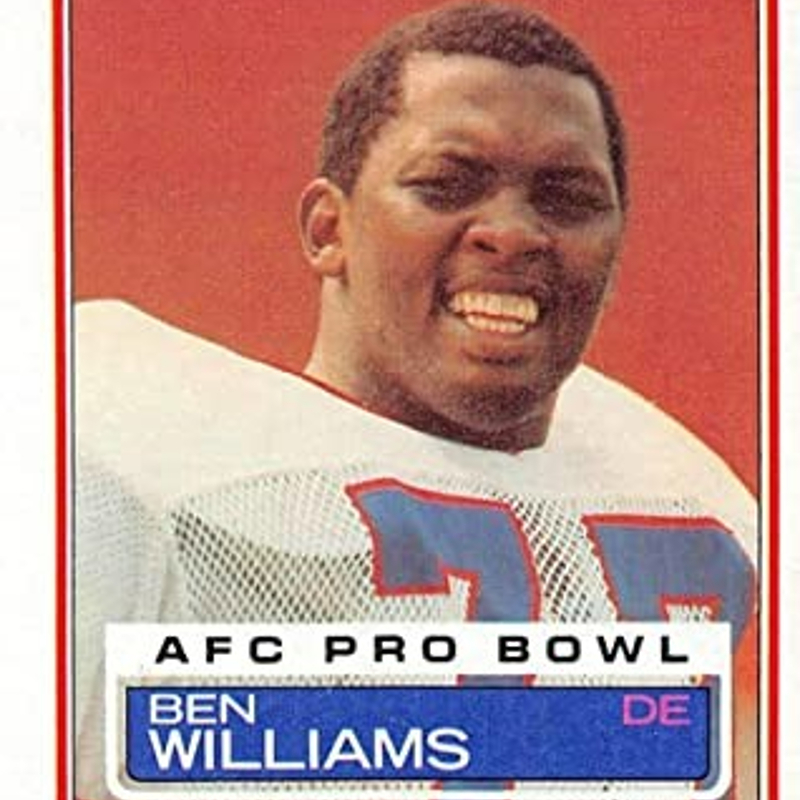

Over 10 seasons in Buffalo, Ben Williams amassed 52 sacks, played in three playoff games, and was named to the 1982 Pro Bowl team. Pro Football Hall of Fame defensive end Bruce Smith arrived in Buffalo in 1985 and credits some of his success to Ben’s tutelage.

“I certainly owe a lot to Ben for embracing me as a young rookie coming into the league,” said Smith to the Buffalo News in 2020. “And not only on the field, but off the field as well.”

Ben’s work ethic made him a football star, but his industriousness was not reserved for football season. Ben returned home to Mississippi every offseason with the Bills to work for a bank in Jackson. For his off-the-field hustle, Ben’s Buffalo teammates called him “Dollar Bill.”

Ben retired from football after the 1985 NFL season. He, Linda, and their three children, Rodrick, Aisha, and Jarrett, relocated to Jackson.

Once in Jackson, Ben started his own company, LYNCO Construction. As busy as he was, Ben maintained the generous spirit he had at Ole Miss. He was very active in local charities, especially those benefitting children.

“He never did stop,” said Linda. “Anytime anybody needed something, they would call Ben and he was there.”

A Different Ben

Ben had always been easygoing and unflappable. If he ever had a bad game, he processed his frustration by watching hours of film to correct his mistakes.

But as Ben entered his 40s, his anger began to flare up. His whole life he had been the big man on campus and a beloved teammate. Little by little, Linda noticed some of his closest friends stopped hanging around as much. Later, she learned those friends had not left Ben – Ben had rudely pushed them away.

Linda experienced this new side of Ben, too. When she came home from work, she often noticed Ben stewing in anger in a way he never had before. The mood swings were so alarming and so out of character that family and friends no longer recognized the Ben they once knew.

In the next decade, Ben’s mood swings lessened, and he became more docile. As Ben mellowed, he started experiencing a new set of challenges.

Ben was struggling cognitively, and it sometimes took him days to recall the answers to some of Linda’s questions.

At this point of Ben’s life, re-living the past was much easier than managing the present. He struggled to remember anything short-term, but he came alive in conversations about his days at Ole Miss and with the Bills. He loved watching “Sanford and Son” and old John Wayne and Clint Eastwood movies – anything with a familiar plotline he could follow.

Ben’s driving became problematic as time went on. He routinely got lost on his way to events. Friends often told Linda they saw Ben aimlessly driving around town and were worried about him.

“He wouldn’t tell me he needed help because he didn’t want me to know,” said Linda. “He just pushed himself and made himself do things.”

Ben hid the full extent of his issues for as long as he could. After the house burned down in 2019, Linda and Aisha were trying to reconcile the family’s sudden financial problems – as “Dollar Bill” could no longer handle finances like he always had. They realized Ben had not been going to work every day for nearly 10 years like he said he was.

“Be Gentle”

Ben’s physical health and cognitive state eventually required full-time care. Linda quit her job to fill the role.

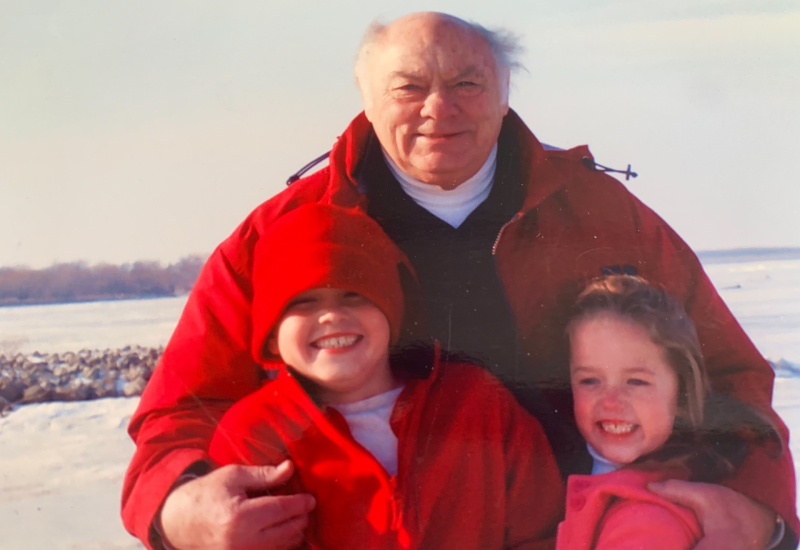

After the fire, many of the friends who had become strangers since Ben’s 40s soon came back around to visit. They laughed with Ben through old memories and old games. For all the joy, Linda remembers many of Ben’s old friends leaving their home in tears over the condition he was in.

In April 2020, Ben suffered a stroke and was placed in a rehabilitation center. The COVID-19 pandemic had struck a month earlier, so the family’s ability to visit him was limited to speaking to him through a glass window.

On May 17, Linda visited him in the evening. She repeatedly called his name to get his attention. Finally, Ben turned to the window, looked at Linda, and said, “Hey, Linda. I see you.”

Ben Williams died the next day.

Towards the end of Ben’s life, a group of retired ex-players in Mississippi reached out to Linda and recommended she donate his brain to the UNITE Brain Bank for CTE research. Linda was vaguely aware of CTE and had seen news reports about former NFL linebacker Junior Seau’s CTE diagnosis years earlier. When Ben died, she agreed to donate his brain.

Months later, researchers informed Linda that Ben had between stage 3 and stage 4 (of 4) CTE. The severity of Ben’s CTE surprised Linda. Ben had never talked about his concussion history or raised any concerns about having CTE.

“He was strong,” said Linda. “Even though he was having those problems, he was fighting it.”

Linda wants to share Ben’s story and CTE diagnosis to help explain to those who knew Ben why he may have exploded on them and alienated them years ago.

“I want the people who thought he was crazy to know that he was not,” said Linda.

Sharing his story also honors Ben’s lifelong legacy of helping others. Linda knows there are other spouses like her and other former players like Ben who could learn from their journey. Armed with the knowledge she has now, she says she would encourage spouses worried about a loved one with suspected CTE to seek professional care.

Linda also urges other loved ones of suspected CTE to pray, to practice empathy, and to remember Ben’s first nickname.

“Be gentle,” said Linda. “Be calm, and don’t fault him.”

Rick Williams

Beginning this piece of legacy writing was not an easy feat for myself, as I still find immense heartache in the loss of my father, friend and hero. I feel it appropriate to state before this piece: “This one’s for you dad, I’ll give it a 110%!”

Beloved husband, father, son, brother and friend

By Sheena Williams, Rick’s daughter

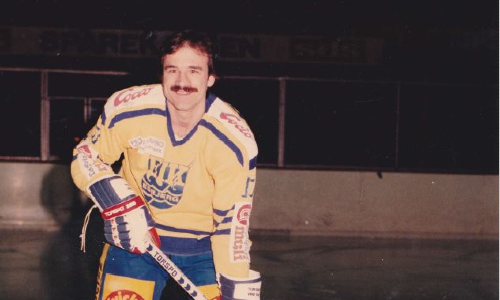

Born in Lampman, Saskatchewan to Betty Lou Bryce and “Butch” Clarence Williams, Ricky Emil Williams joined his older brother Russell, where they spent a short time before moving to Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. It was during dad’s days in Saskatoon where he picked up his deep seeded love for the game of hockey.

Dad played for the SJHL Saskatoon Olympics, before joining the Saskatoon Blades, playing in the WHL. It did not take long before he was traded for his arch nemesis/best friend George Pesut in Victoria at the ripe age of 17. I will never forget dad’s stories during this time as he described – “just how lucky hockey players have it these days…back in my day, I had to bus it with no heat to a place called Flin Flon, Manitoba to play a game, and back again!” I believe that if you were lucky enough to know dad, you were privileged enough to learn about Flin Flon, Manitoba.

From there, dad played for several different teams, including the Spokane Flyers and the Nelson Maple Leafs before attending the University of Calgary on a hockey scholarship to join the Dino’s. It was here that Dad met many of his longtime friends – the FOR’s (Friends of Ricks). This was also the time when dad met my Nana, June Tarves and their wonderful family. The story goes that dad was looking for a place to stay while attending University. Lucky for him, his friend Shane knew the perfect place – at his mother’s house. Now Nana, being the ever welcoming type could not say no, and allowed dad to stay for the period of his kinesiology degree. Dad quickly became a part of their family, and soon considered June to be a second mother.

Dad’s time spent at the University of Calgary was a tremendously joyous time. Not only was he able to meet many of his lifelong friends, but was awarded Canadian Defensemen of the Year. An incredibly skilled hockey player, dad not only played the role of defense, but also as the team “goon.” Short in stature, dad always mentioned needing to make up for his size in other ways which included fighting and/or taking a dive in front of the puck; whenever dad played, he played his heart out.

From University, Shane Tarves (June’s son) was able to pull some strings to have dad join him in Europe to play. Dad played in both Denmark and Germany, where he met his wonderful wife Susanne (originally from Denmark). Dad played several years in Europe, before deciding to move back to Calgary with Susie to start a family, and lay down some roots.

Shortly after settling down in Calgary, Susie became pregnant with their first child, Sheena (that’s me), and their son Luke a few years later. It was at this time that dad began his work with the Calgary Board of Education as a substitute teacher. After some time at different schools, dad was able to establish a position as a Phys Ed teacher at Fairview Junior High.

Dad’s love for teaching was undeniable. The passion that he poured out into teaching children was an enviable quality of any teacher; to state it more blatantly, dad just “got kids, it was a part of his being”. He was able to connect with them not only on a surface level, but was able to impact and change many lives over the course of his career. To solidify just how impactful dad was, a message from a former students…

“I was a student at Fairview junior high. I was not the most athletic kid and was picked on constantly by the other students. I fell into depression through-out these three years and was almost ready to quit. But one day when I was too ashamed to leave to the locker room Mr. Will came in to talk to me and I will never forget the words he said to me. He told me no matter how many times you take a hit you have to get up and fight for yourself, it doesn’t matter what the crowd thinks it’s what you do that matters. This was the first time in a long time that I had felt like some one cared for me and these words stuck with me. Because of what Rick said to me I am now in university following my dreams. Rick Williams changed—no saved my life without even knowing, and for that I am thankful. He was a great man who treated students with more respect and compassion than any other person I have ever met.”

For those of us lucky enough to know dad, we are all better for it. In both sickness and in health, dad was always a presence that one would gravitated towards – he was magnetic. Growing up, I always thought of my dad much like any other dad – strict, rule making, expectation upholding, and curfew setting…but it was not until my later years that I realized just how magically special my dad truly is, and was. I am confident in saying that I would not have turned out to be half of the woman that I am today without the love, guidance and expectations that my dad placed upon me each and every day – “just be a good kid and good things will come to you” he would repeat – something that my brother Luke and I will never forget.

When dad became ill, it was, at first a gradual decline. Small things were forgotten such as key placement, what we ate for breakfast, etc. – everyday things that many people tend to forget or misplace. From here, it grew more and more present that dad was losing both his short and long-term memory. He began to forget directions to familiar places such as the hockey rink and Tim Hortons; it was now that he began to become more erratic and fearful. Dad knew that he was changing, but did not understand why, or to what extent; none of us did.

Dad was placed on Long-Term disability from work, and took a turn for the worst as he began losing most of his working memory, as well as fabricating stories that he was sure took place. Due to the severity of aid that Dad began to require, he was welcomed into the care of health professionals where he was able to receive the assistance and monitoring that he began to need. This decision was heartbreaking to his immediately and extended family. Sleepless nights, tears and angst accompanied most days spent missing and worrying about dad. Could he come home? Did he understand why he was there? Is he upset with us?…the uncertainties never seemed to subside in the hearts and minds of loved ones.

After some time, dad was placed in the Bethany Harvest Hills Care Centre, and what a blessing this was. The atmosphere, nurses, and healthcare professionals were a Godsend to dad and to our family. Dad was not only treated with compassion and respect, but was most importantly loved by each person that cared for him. They made Dad a priority each and every day.

Dad spent the rest of his life at the Bethany Care Centre, before passing away in his room November 15, 2014 with his family all present to send him off. At the age of 60, this was not easy to accept, but was understood based on dad’s condition. We later found out that Dad was also diagnosed with Colon Rectal Cancer, as well as pneumonia in his final days. I can speak only for myself in saying that the amount of heartache still felt in regards to the loss of my father is overwhelming.

When dad left us that day, he took a part of each of us that will never be replaced. I still feel dad in all that I do, and remember many of his quotes and qualities that I both live by and attempt to emulate on a daily basis. We lost an incredible human being that day, but God gained an angel. I often feel as though God took dad too early and that I wasn’t ready to lose my father, but now understand that he is always with me, and with all of us. I can still hear him telling me to weed whack the grass edges a bit closer, asking me if I’d like to come to “Timmies” for a coffee, or asking me what I was going to order off of the restaurant menu so that he could order the same.

We love and miss you more than you will ever know dad. I promise to always “be a good kid”, and know that good things will come to me because I am a part of you.

Until we meet again Dad – I love you.

Sheena Lou Williams

Click here to read Rick’s story from the Global News.

Click here to view the news clip from Alberta CTV News.

Sam Williams

Stanley Wilson Jr.

Stanley Tobias Wilson Jr. was a compassionate, talented, and courageous man who died Feb. 1, 2023, at the age of 40. He was the blessed, beloved, and only child born from the union of Stanley Tobias Wilson Sr., and Dr. D. Pulane Lucas. Stanley was born on November 5, 1982, in Oklahoma City, about 20 miles from where his father played football at the University of Oklahoma. Stanley later lived with his parents in Cincinnati, where his father was a star NFL running back with the Bengals. Stanley would eventually move to Oakland, Calif. with his mother.

Stanley lived in the Bay Area while his mother completed her undergraduate degree. When she decided to relocate to New England to further her education, Stanley’s paternal grandparents, Henry and Beverly Wilson, became his loving and legal guardians in Carson, Calif. This move allowed Stanley to remain close to his father, relatives, and numerous friends while attending Frederick K.C. Price Christian School. At Price, at the age of 13 in the 9th grade, he was introduced to football, and he began to thrive as an athlete.

Growing up, Stanley also spent time in Boston with his mother, who was studying at Harvard University. He enjoyed serving as a ball boy for the Harvard University basketball team, attending classes with his mother, and walking around the university and Harvard Square. But a brutal winter, combined with a longing for athletic opportunities and the entertainment and holidays at his grandparents’ home led him back to Carson in the custody of his grandparents.

Upon his return, Stanley enrolled in Bishop Montgomery High School in Torrance, where he became a standout football player as a safety and member of the track team. He also performed in theater productions, served as a calculus tutor, and was crowned homecoming king.

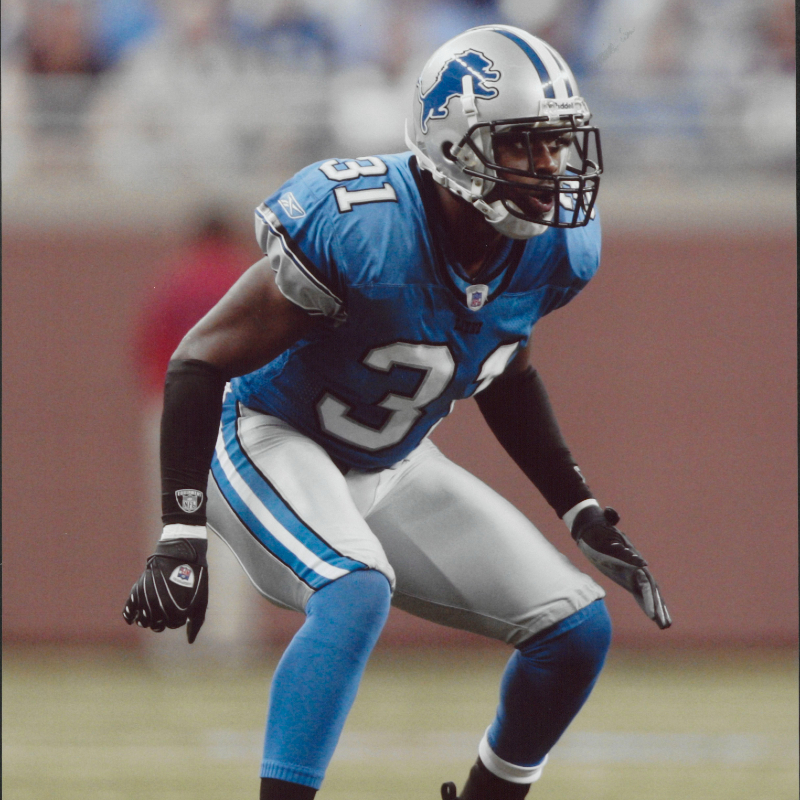

Stanford University recruited Stanley to play defensive back for their football team from 2001-2004. As a senior, he recorded career highs for both tackles and pass breakups, earning an honorable mention on the All-Pac-10 team. Stanley also proved to be a dominant sprinter on the Cardinal track team, posting some of the school’s best results in 100 and 200-meter events. His 100-meter time of 10.46 is still the fourth-fastest all-time by a Stanford athlete.

Stanley’s peers elected him to be a senator in Stanford’s Associated Student Body. He pledged Omega Psi Phi Fraternity (Alpha Mu Chapter) and served as vice president (2003-2004). Stanley became a mentor in the Children’s Visitation Program, where he focused on inspiring youth with incarcerated parents to become positive assets in society. In 2005, Stanley graduated with a B.A. in Urban Studies.

The Detroit Lions drafted Stanley in the third round of the 2005 NFL Draft. He focused on becoming a premier football player and second-generation NFL player. In 32 NFL games, Stanley Jr. racked up 86 tackles, eight pass deflections, and one forced fumble. In 2007, he was placed on injured reserve due to a knee injury, then re-signed to a one-year deal. Unfortunately, he tore his Achilles tendon during an exhibition game against the New York Giants, ending his career in the NFL.

Regardless of his situation, Stanley made time to volunteer and help those in need. From 2005-07, he was a motivational speaker, inspiring high school students to focus on education, health, fitness, and achieving their goals.

Stanley cherished spending time with family and friends, driving, reading, conducting research, and listening to music. He traveled the world, to places like the Caribbean, Italy, South Africa, Australia, Israel, and Egypt. He was an avid learner with a brilliant mind. He knew a quality education, real-world experiences, and a network of friends and mentors were critical for him as he transitioned into a successful post-NFL career.

In 2008, Stanley completed a certificate at the Aresty Institute of Executive Education and the Wharton Sports Business Initiative’s Business Management and Entrepreneurship Program. The Wharton program at the University of Pennsylvania was sponsored by the NFL and the NFL Players Association.

In 2009, Stanley completed The NFL Player Development Program: High Growth Entrepreneurship at Northwestern University. The same year, he enrolled in the Hunter-Bellevue School of Nursing in New York City. He earned his nursing degree in 2014. After graduation, Stanley worked in the healthcare field in New York and later relocated to Portland, Oregon. He eventually returned to Carson to live with his grandmother.

Throughout his life, Stanley was a team player who cherished his friendships and valued his relationships with teammates and fraternity brothers. He courageously accepted new challenges with a strong faith in God and love of family. Stanley greeted each new day resilient with hope, optimism, purpose, and drive. He never stopped longing for the life that he knew he deserved.

Yet, over time, Stanley’s behavior reflected the signs of his struggles with the trauma of same gender childhood sexual abuse, mental illness, drug addiction, and indications of chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), a condition that links brain degeneration to repeated hits to the head. Having been deemed incompetent to stand trial, Stanley spent the final months of his life in the custody of the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department (LASD). He died under suspicious circumstances.

Stanley Wilson Jr.’s family would like to thank the Detroit Lions, Stanford University, Bishop Montgomery High School, Frederick K.C. Price Christian School, and many of Stanley’s friends and teammates who have shared their condolences, kind words, and memories.

Wade Wilson

Jeff Winans

Beloved husband, father and friend

Jeff was 6’5”, well built, and extremely handsome, reminding me of a Greek God with his curly black hair, deep brown eyes and a sculpted black beard. His smile and laugh were infectious and would brighten up any room. He was born in a small agricultural town in North Central California called Turlock, where melons, turkeys, nuts and wine were their major source of income. Blue Diamond Almonds and Gallo Winery’s corporate offices were just up the street in Modesto.

His father, Glen, had a local State Farm agency and his mother, Janice, was a homemaker. He grew up with two older sisters, Shari and Sandra. Everyone knew everyone in Turlock. Jeff excelled in sports, playing basketball, football and track at Turlock High School. Upon graduating from high school in 1969, he went to Modesto Junior College in Modesto, California, where he became the only six-letter winner in basketball and football. The college also claimed, in 1993, at his induction into their Hall of Fame, that he still held the record for the most unpaid parking tickets.

In his second year at Modesto Junior College, his lifelong dream came true. He was offered a scholarship to USC in Southern California to play football for Coach John McKay.

His first year at USC was a real eye opener, especially coming from a small agricultural town. He struggled with his academics and the big city life. However, in his second year there, he came to life on the field and was moved to first string. That year, he received the 1972 “Most Improved Player” award from Coach McKay.

His USC football team went on to become National Champions, winning the Rose Bowl in 1973 against Ohio State. Thirty three percent of the players were drafted to the pros. Jeff was second round draft pick (#32) and went to the Buffalo Bills. He played six seasons with the NFL. He loved the game and had a strong connection with his teammates.

Jeff started nine games in 1973 as defensive tackle. A torn ACL took him out for part of the season. In 1976, Jeff was traded twice, first to the New Orleans Saints where he played only three games, and second to the Oakland Raiders with Coach John Madden. At that time, Madden decided to move him to offensive guard. An unexpected trade took him to Tampa Bay in 1977.

Jeff fit in well at Tampa and McKay (his former USC Coach), kept him at offensive guard. December 12, 1977, after being 0-26, the Bucs won their first game against New Orleans. Jeff was back on his game but it was short-lived. In 1978 he sustained major back, neck and more head injuries–forcing him to sit out the rest of the season.

The first time I saw Jeff, he was visiting some of his friends from Buffalo at the apartment complex I lived in in Clearwater, Florida. My roommate introduced us at a local bar June of 1979. We started dating and in August during an exhibition game, his foot was injured and he was waived by the Bucs. A few months later he was picked up again by The Oakland Raiders. By that time Jeff and I had fallen in love and he asked me to go with him.

Our move back to California was an exciting one and we took up residence in Modesto. Jeff worked very hard and was back on track but in the 1980 Season, Jeff was injured with a crushed ankle. The Raiders went on to win Superbowl XV. July, 1981, after refusing to sign a waiver on his ankle and back, Jeff’s career as a professional football player ended. It was a crushing blow for him and I was thrown into the role of sole support of the family. Our talk of marriage was hard for him because he wanted to be able to support me the way he had in the past. Two months later a long weekend trip to Reno to see Smokey Robinson turned out to be a surprise wedding that he had been planning for months. We were married December 19, 1981.

He was offered a job at Modesto Junior College, but embarrassed after three days, he had to quit. His headaches, depression and physical injuries from football took a toll on him. His Sleep insomnia became worse. He started seeing a psychologist, and we worked through the next few years. In 1984, things were looking up so we decided to try and have a baby. November of 1984, Jeff sustained a life threatening gunshot accident while we were moving and wasn’t expected to live. A few days later the blessing came when I found out I was pregnant with our only child Travis, born August 2, 1985, our greatest blessing.

After multiple surgeries, infections and bankruptcy, the fall of 1988, we decided to move back to Florida. A few years later, Jeff’s right leg below the knee was amputated. He met Michael Reith with St. Pete Limb and Brace who fitted Jeff with a prosthetic and Jeff started volunteering with Mike, talking to other amputees. It was the first time in a long time I had seen Jeff so excited.

In 1992, he founded Day For Our Children, Inc., a 501(c)(3) to help abused, neglected kids and families who fell thru the government cracks or whose children needed surgeries that insurance companies wouldn’t pay for. A year later, he brought Outback, GTE wireless, Continental Airlines and ASI Building Products on board as major sponsors. We didn’t know how to raise money, but Jeff knew golf and he started some of the first Celebrity Golf Events in the Tampa Bay area. We met Tom and Lisa McHale at a fundraising event in 1993. Lisa and I have recently shared those photos and reflected on those wonderful times. In 1996 he became President of the Local NFL Alumni Chapter and was able to recruit more former players in the area to join. He was an excellent president and I was so proud of him. But his headaches and back and arm pain, numbness, and insomnia continued. It was more than he could handle and in 1998 I took over as President of the foundation.

Our son Travis started high school in 1999 and like his Dad, excelled in basketball. Travis was Jeff’s everything and he was able to work with him on his game and he was a wonderful father. By 2001, I was noticing more memory lapses, which I attributed to the prescription drugs he was on. Conversations we would have he didn’t remember which would turn to anger and frustration. His decision making and spending got out of hand and he began overdrawing our accounts. In 2002, he decided to get help and was diagnosed with Manic Depression/Bi-Polar and Borderline Personality Disorder. The Doctor put him on Lithium and Wellbutrin XL. It seemed to work for a while, and then he became more erratic with obsessive compulsive behavior making sure everything was in its place at all times. For a few weeks at a time, I would have my loving Jeff back and the loving wonderful man I knew. Then without warning, he would explode. He would have to write everything down four or five times. He would make plans and then stiff people. He became a recluse except for only a few close friends.

We separated in October, 2005, and he moved back to California. We stayed close and I still worried about him all the time. April, 2007, our son Travis decided to move out to California to finish school and play football. I was so happy that he and Jeff could be together again and the family bond began to reignite.

May of 2007, I was housesitting at my girlfriend’s home and came upon a TV show called HBO’s Real Sports with Bryant Gumbel. Bernie Goldberg was interviewing a young man named Chris Nowinski, author of Head Games, about his advocacy work raising awareness of the devastating consequences of sports concussions.

As Chris described the symptoms and long-term side effects of multiple concussions and repetitive hits to the head, a large knot in my stomach took me back to the deadly emotions over the years that at that time, had taken my marriage to a point of no return. I began to question if the emotional and behavioral problems that Jeff had been experiencing most of our married life were not what I thought they were, but possible after effects of his eleven-plus concussions and repetitive hits to the head, from playing professional football. I needed to know more about these concussions, so I found Chris on the internet and emailed him. Within twenty-four hours, he emailed me back and we set a time for a phone conversation a few days later. I told him about our story and that people have no idea what the families go through. He encouraged me to come to Washington DC for the Press conference and hearings. I was shocked to find so many other families going through the same thing.

Over the next three years, I became a sponge learning about concussions and I knew it was God that directed me to that HBO channel because if it hadn’t been for Chris’s interview, I never would have thought that Jeff’s problems could have been attributed to concussions.

In 2010, Travis moved back to Florida and Jeff and I started to re-kindle our romance. I was able to get Jeff into rehab at The Summit Recovery Lodge in Utah, June 2010. It was there Jeff found his spirit again. February 2012, Jeff flew here for a visit. He decided to make the move back to Florida. Travis was so excited to have his Dad back here. We both missed the family unit and our love for each other was stronger than ever. October 2012, on a two week visit with him in California, we decided to tell Travis we were back together and made plans to remarry, March 2, 2013.

But God had a different plan and on December 21, 2012, he took Jeff home. He was the love of my life; a kind, sensitive, loving man and my best friend. I know when he passed there was love, peace and joy in his heart. My goal now is to educate, promote the research and help as many families as I can. It’s an honor to share our story and I want to thank Chris for all the hard work and forming the Concussion Legacy Foundation. Together we are one.

To learn more about Jeff and Brandi’s story read Brandi’s memoir, The Flip Side of Glory, on Amazon, Kindle and Nook.

Dennis Wirgowski

Superman

If it was a goal of Dennis Wirgowski’s, it was getting done. Born in Bay City, Michigan in September 1947, Wirgowski was an outstanding natural athlete made even better by a devout work ethic. Wirgowski had the talent to go far in baseball, basketball, track, or whatever sport he settled on. But Wirgowski’s best sport was football. His tall and bricklike frame made him a tremendous lineman.

Wirgowski accrued many nicknames in life. Some of them were easy products of his name. Denny. Wirgo. Others, he earned.

Opponents trying to block Wirgowski simply bounced off him while at Bay City Central High School. Len Hoyer of the Detroit Free Press likened Wirgowski’s discarding of opponents to that of Clark Kent’s discarding of evildoers. Dennis Wirgowski was dubbed “Superman.”

After a prolific high school career, including an undefeated Michigan Class A State Championship run in 1965, Superman chose to attend Purdue University. Wirgowski’s winning streak traveled with him to West Lafayette and the Boilermakers finished 8-2 in each of his three seasons with the team.

He was selected in the ninth round of the 1970 NFL Draft by the Boston Patriots. He played three seasons there before being traded to the Philadelphia Eagles where he played for one season. In 1974, he tried out for the Cleveland Browns but was cut before the season started. Injuries forced the Browns to call Wirgowski for another shot, but he declined and retired from football at age 28.

Nuts

After a brief stint living in California, Wirgowski moved back home to Michigan. He earned a teaching degree and worked as a warehouse manager for Stevens Worldwide Van Lines.

Wirgowski teamed up with a friend named Denny Nusz to start Backstreets Bar, one of Bay City’s first sports bars. The name Nusz lent itself to the nickname “Nuts,” which became Wirgowski’s catchall word. He said “hey Nuts” to Nusz or any bar patron whose name he couldn’t remember. Over time, Nuts stuck as another of Wirgowski’s nicknames.

Wirgowski owned Backstreets in a financial sense, but he owned every room he walked into with the power of his spirit. He had a gift of connecting with anyone he met and could make them laugh effortlessly.

At Backstreets and other local bars, Wirgowski’s gregarious personality was on full display. He was infamous for offering to treat anyone and everyone to lunch at nearby Bell Bar. It just so happened their lunch would be the bar’s already complimentary meat snacks.

Wirgowski did open Backstreets’ cashdrawer to sponsor local sports teams. One of those teams was a local softball team, which starred a young woman named Bethany Stewart.

Many bargoers were starstruck by Wirgowski’s celebrity status – but Bethany wasn’t fazed. She preferred his sense of humor, competitive nature, and the way he commanded a room. The two started dating shortly after meeting.

“He had this larger than life personality,” she remembers. “He was the life of the party. He could talk to anybody like he’s known them for a million years.”

Dennis and Bethany enjoyed playing sports, long walks, and traveling. In their travels, the scenery changed but Nuts was still Nuts. During a trip to Boston, his old neighbor appeared and the two talked for hours. In Florida while stopped at a red light, Dennis admired the motorcycle in the next lane over. He and the motorcyclist chatted like old friends through several green light cycles.

After several years of dating and engagement, Wirgowski and Bethany married at a courthouse in Port Huron, Michigan and enjoyed a honeymoon along Cape Cod, Massachusetts.

A different Dennis

The Dennis Wirgowski Bethany fell in love with was incredibly happy-go-lucky. Nothing bothered him. But by his 50’s, Wirgowski became more easily agitated. Bethany saw his mood change from one day to the next.

“His tolerance for things was really short,” Bethany said. “He would get so angry and his temperament was just different. His reactions to things was so irrational.”

The reactions were irrational, but initially harmless. Eventually, they became dangerous.

One day while on his bike, a young motorist drove over a puddle that splashed Wirgowski. Assuming the driver did it on purpose he erupted, and physically attacked him. Police intervened and came to the Wirgowski’s house to inform Bethany.

“He’s riding his bike in the rain,” Bethany said. “I told him I don’t think the kid intentionally drove by you to splash you, but he had that paranoia that people were out to get him.”

It became The World vs. Dennis and paranoia colored Wirgowski’s later years. Something as simple as a mandate to switch his cable boxes from analog to digital could lead to an anxiety attack.

Wirgowski and Bethany loved walking their dogs Coco, Barkley, and Zoe along the beach. One day a neighbor almost hit the dogs with her car. The run-in enraged Wirgowski. He was left banging on the neighbor’s door until the police tore him away.

Wirgowski was not without remorse for his actions. He wrote the neighbor an apology letter the next morning, a testament of the dime-turning his mood could take. Enraged then gentle. Paranoid then sane.

Around this time, Wirgowski began to see similarities between his story and those of other former NFL players he read about in the news. He collected news clippings about Junior Seau and other former players affected by the degenerative brain disease CTE. Wirgowski heartily empathized with one article which described playing football as running into a concrete wall at full speed.

Bethany repeatedly encouraged her husband to seek help. She was finally successful in September 2013 when Wirgowski agreed to see a therapist. He was stoic upon his return from the visit, offering no details to Bethany.

She asked if he had told the therapist about his football career. Wirgowski insisted that wasn’t important. Bethany, an ER nurse, reached out to the therapist and disclosed his football career and his new hobby of clipping news stories in confidence. The disclosure got back to Wirgowski, causing him to explode on Bethany. He never sought help again.

Perfect storm

On January 25, 2014, Bethany woke up to hear Wirgowski shoveling their driveway. When he came back into the house, he told Bethany he loved her and walked back out the front door.

Later that day, Dennis Wirgowski took his life. He was 66 years old.

Wirgowski’s suicide devastated Bethany, Dennis’ family, and their community. She couldn’t escape the guilt of not acting sooner.

“I knew he was sad, I just didn’t know he was suicide sad,” Bethany said. “Being a nurse, I felt like not only a failure to my profession, but also to my husband, and to his family, because I had lived with him.”

Bethany says she and Wirgowski’s many close friends missed signs to get him help. She counts the news clippings, the depression, and his personality shift as calls for help that he wanted to talk to someone. She sees his outrage over her contacting his therapist as his worry that Bethany was connecting the dots that he was contemplating taking his life.

At the same time, Wirgowski’s impulsivity may have shrouded any potential warning signs.

The day before his death, Dennis called Bethany to make sure she got his prescription for an antibiotic filled so he could get his teeth cleaned.

Five months prior to his death, Wirgowski fell off his bicycle and broke his hip. He had surgery to replace the hip and worked out every day for four months to rehab. His diligence paid off and his hip healed.

“Why would somebody rehab that hard and then take their life?” wondered Bethany.

With his recovery from hip surgery, Wirgowski had once again conquered something he set his mind to. But was then devastated to learn his knee would also need replacement.

“There were a lot of things for that perfect storm for him to want to take his life,” said Bethany.

The American Foundation for Suicide Prevention says there is no single cause for suicide. It most often occurs when stressors and health issues converge to create an experience of hopelessness and despair.

Knowing her husband needed help, Bethany wishes she had asked him one question.

“It just will probably, always traumatize me that I didn’t ask that little question, ‘Are you thinking of suicide?’” Bethany said. “Because learning what I know now, that’s what people want you to ask. I have it in my mind if I would have asked him, he probably would have broken down and told me.”

Relief

After Wirgowski took his life, Bethany looked through his email. She found he had been corresponding with a former NFL player who was a vocal advocate for concussion awareness at the time. Bethany emailed the player to inform him that Dennis had taken his life and the player informed Bethany about the option to donate Dennis’ brain to the UNITE Brain Bank in Boston. She immediately agreed.

Researchers at the Brain Bank diagnosed Wirgowski with Stage 2 to 3 (of 4) Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE).

Bethany felt relieved by the results. The diagnosis helped to explain Wirgowski’s personality changes and bizarre actions. Still, Bethany knows she only saw the tip of Wirgowski’s symptom iceberg. He had efforted to hide his struggles from her.

Those with CTE can experience symptoms such as depression, rage, and suicidal thoughts, but we still need to know more about why these symptoms occur. Research is ongoing at the Brain Bank to uncover the relationship between CTE pathology and psychiatric symptoms like depression and suicidal ideation.

Looking forward

Wirgowski’s suicide launched Bethany into suicide advocacy. She and other impacted families participate in Midland, Michigan’s Walk for Hope, an annual 5K walk that promotes suicide awareness.

She met Barb Smith, founder of the Barb Smith Suicide and Resource Network. Barb helped Bethany tremendously in the months following Wirgowski’s death. Bethany became a safeTALK trainer to educate others on how to talk with someone who may be suicidal. Barb contracts Bethany to give safeTALKs to those in need.

“I was an ER nurse at that time for 17 years, and I only knew suicide from a distance and never had any type of formal training on what to recognize or what to ask,” Bethany said. “You don’t have to fix anything. You just have to realize how to identify it. And people aren’t always as direct as we would like them to be. And that’s why you have to read into what people are trying to say to you.”

Bethany also helps run an annual football camp in her husband’s name. The camp is a free, one-day event for local children that focuses on football skills as well as mental well-being of young athletes. Last year, camp attendees heard the Concussion Legacy Foundation Team Up against Concussions speech about the importance of speaking up for a teammate who is showing signs of a concussion. Local coach Dick Horning gave the speech and connected its message to his late friend Wirgowski.

“The whole speech was amazing. There wasn’t a dry eye in there,” said Bethany.

Six years after Dennis’ death, Bethany’s grief and “what-ifs” persist. But so too does the image of her Superman, smiling, laughing, and talking sports with a Nuts at the bar.

Suicide is preventable and help is available. If you are concerned that someone in your life may be suicidal, the five #BeThe1To steps are simple actions anyone can take to help someone in crisis. If you are struggling to cope and would like some emotional support, call the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988 to connect with a trained counselor. It’s free, confidential, and available to everyone in the United States. You do not have to be suicidal to call. If you’re not comfortable talking on the phone, consider using the Lifeline Crisis Chat.

If you or someone you know is struggling with lingering concussion symptoms, ask for help through the CLF HelpLine. We provide personalized help to those struggling with the outcomes of brain injury. Submit your request today and a dedicated member of the Concussion Legacy Foundation team will be happy to assist you.

Edward Wolf

Ed was a man of many talents who excelled both academically and athletically. He held an impressive list of accomplishments in his lifetime, both on and off the field. He was a minor league baseball player, a four-sport varsity letter athlete, a member of the Army National Guard, and was inducted into two local halls of fame.

Born in 1939, Ed’s love of sports began when he started playing football in grade school and continued to play through high school and college. He was first team all-city for football, but his athletic accomplishments did not end there. During his time at Deer Park High School in Cincinnati, Ohio, he lettered in four sports: football, baseball, basketball and track.

Ed then attended the University of Cincinnati where he continued his athletic career and lettered in football and baseball. He was a member of the Sigma Alpha Epsilon fraternity and the Sigma Sigma honorary fraternity.

He later signed with the Houston Colt .45s, a minor league baseball team, and was a catcher for two years. His years of playing sports and childhood concussions led him to experience many head injuries. After his time in the minor leagues, Ed was in his twenties and gravitated away from sports. He joined the National Guard and proudly served for six years. We met during our college years, married, started a family and Ed began his career. He pursued his MBA at Lake Forest Graduate School of Management and led a successful career in executive sales and marketing. He was the director of the Port of Wilmington. He traveled the world and enjoyed the challenge of this multi-faceted, but politically vulnerable job. In the ’90s, Ed reentered the job changing pattern. We had relocated many times to Kentucky, Illinois, Florida, Delaware, and back to Cincinnati for his retirement. It is difficult to pinpoint but somewhere in this history was the onset of the symptoms. I remember his comment, “I just can’t seem to find the right situation where I can be all that I want to be. Something seems to be blocking me, something seems to be getting in my way.” Overall, Ed did not appear to be conscious of the challenges of CTE.

Looking back, inexplicable behaviors seem to form a profile indicative of the disease. In his later years, Ed displayed cognitive impairment with the inability to problem solve or strategize. He loved to sing and was a member of his local chorus. But after two years he could no longer participate. The effects of the disease took its toll in many ways.

We were fortunate because the slow onset of symptoms meant it did not have a great impact on our family life while raising our children. Looking back, I remember he experienced some agitation and depression, and it was in the last two decades of his life that we noticed changes in his personality and behavior. He was a humorous guy and relished the role of loving father and coach for the kids’ baseball, soccer, and softball teams. His daughter Leslie relates, “He was the dad who was always there, and that presence gives much joy to the memories of our childhood and adult life.”

Ed was an all-around good man. The impact of the disease was irrelevant to that goodness. He had many friends and loved and cherished his three children, five grandchildren and his grand dogs. These relationships brought him much joy throughout his life. The times Ed spent with his family were the times when the symptoms and challenges he experienced from CTE seemed to be minimal. It felt like a true gift to know that despite the changes happening to Ed, his family meant so much to him.

During his life, Ed worked with a neurologist who helped us narrow down the cause of the dementia and we knew CTE was a high possibility. In retrospect, it is clear how much of his behavior was likely caused by CTE and it is hard for families to watch the demise of a loved one and not know what is happening to them.

A few years prior to Ed’s passing, our daughter, Wendy, discovered the Concussion Legacy Foundation and the UNITE Study at the Boston University CTE Center. She registered his willingness to participate and made the brain donation possible. Though his CTE diagnosis wasn’t a surprise, it was difficult for us to accept.

For him, the playing of the sports, the recognition of his abilities, the joy that he got, the commitment, the determination that he had, seemed for him to be the reward that he remembers. The actual outcome and the price that he paid for that, I don’t think he was ever cognitively aware.

It is important that athletes know the risks of sports from an early age. Our family is happy to know that Ed’s final contribution and legacy are part of crucial CTE research. There are so many famous athletes that have contributed, and it was just very exciting that our guy, his brain, was just as valuable. That made us feel that this was his very best contribution that he could make.